By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

After Crimea now

Eastern Ukraine?

As Russia fortifies its

position in Crimea, Eastern Ukraine will be

the next region to watch in assessing the evolution of the Ukrainian crisis.

Eastern Ukraine, like Crimea, is politically oriented toward Russia, in

contrast with the more Europe-leaning western and central parts of the country.

However, there are significant differences between Crimea and Eastern Ukraine

that will make a Russian military intervention there unlikely for a number of

reasons.

The situation in the Ukraine thus is delicate, to say the least. On

balance, Russia is probably where it wants to be given its inability to prevent

the initial ouster of Yanukovych.

One of the latest developments in Russia’s attempted invasion of the

Crimea last night then, was the sinking of a Russian warship, in order to help block the Ukrainian ships in Donuszlav lake, including the missile

cruiser Moskva.

This action serves several purposes for the Russian forces operating in

Crimea. It provides a way, albeit and impermanent one, for Russia to free up

military assets for other uses. The Kremlin's operational planners still want

to deny Ukraine the ability to concentrate force as the crisis continues, so

isolating Donuzlav Lake is thus a prudent move.

Not surprising, during the past few days, threats have flown back and

forth across Eurasia as a result of the ongoing Ukraine crisis. Russia is

committed to its long-term goal of ensuring a neutral Ukraine, which it

considers part of its sphere of influence, as a buffer with the European Union.

While Moscow is willing to accept Ukrainian neutrality, EU and NATO integration

is a red line for the Kremlin. Russia has threatened to use powerful economic,

political and military levers to pressure the fledgling government in Kiev and

its European supporters. In the meantime, the Europeans have repeatedly warned

of impending sanctions should Russia keep its troops in Crimea and refuse to

negotiate with the interim government in Kiev.

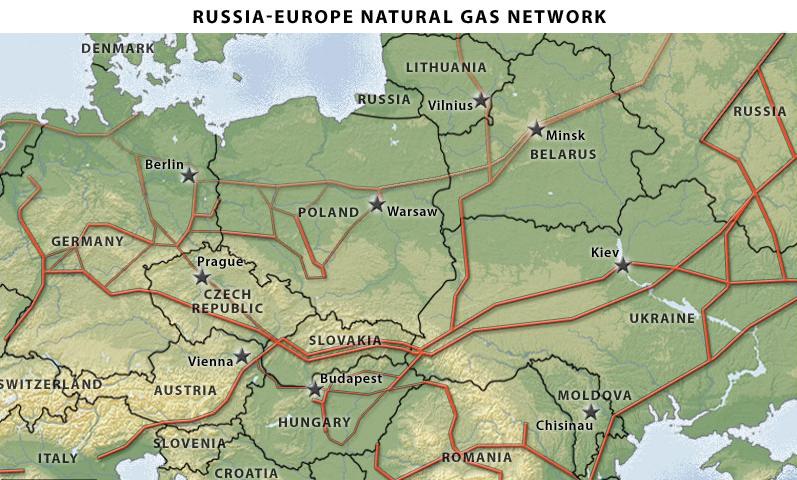

The Kremlin has warned of plans to award Russian citizenship to native

Russian speakers across the former Soviet periphery, to cut off natural gas

supplies to Ukraine, to annex Crimea and to discontinue U.S. inspections of

strategic nuclear missile facilities. Russia is using these threats to

highlight its ability and willingness to disrupt Europe's basic economic and

defense structures.

In response, the European Union has also been publicly building up its

leverage vis-a-vis Russia. On Monday, Brussels put its decision regarding the

OPAL pipeline and its negotiations with regards to South Stream on hold,

reminding Russia of its financial reliance on European customers and

distribution networks.

Both sides have refrained from acting on the most significant of their

threats, each waiting to see what step the other will take over the coming

days. The threats are meant to display each side's respective leverage.

Actually following through with them is another matter.

For Russia, the costs of acting on its threats are enormous. Though

Russia already has a strongly protectionist economy, new trade restrictions on

Ukraine would still harm Russian industry, especially in regions bordering

Ukraine, where Russia's already-struggling regional economies are closely

linked to Ukraine's industrial east. Cutting natural gas exports to Ukraine

would reduce Gazprom's revenues, while pulling out of the New START treaty or

the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces treaty could potentially draw Russia into

an expensive arms race that would drain the country's limited resources.

Moreover, annexing Crimea sets a dangerous precedent for Russia itself. If

Ukraine can be divided, than separatist regions within the Russian Federation,

such as Chechnya and Tatarstan, which are primarily populated with non-ethnic

Russians, may conclude that Russia itself is divisible. This is also a concern

for countries such as Kazakhstan that are currently in

Russia's camp but are wary of a potential repeat of Crimean secessionism

in their own territories. Ultimately, annexation could also lessen Russia's

influence over Ukraine's political future, since the largely pro-Russian

Crimeans would no longer be able to vote in Ukrainian national elections, at

least in theory.

While Russia does not want its economy, national security and

international influence to suffer as a result of its Ukrainian intervention, it

would be willing to carry out its threats if these remain the only means for

guaranteeing Ukraine's neutrality. Russia previously has shown its willingness

to weather the fallout from similar threats involving energy cuts and military

action in a neighboring country.

For its part, the European Union would also face difficult repercussions

if it chose to follow through on its threats of more significant sanctions and

stalled energy negotiations. Europe's dependence on Russian energy, coupled

with close financial links between the business hubs of Western Europe and

Moscow, translate into steep costs for any disturbance to Russia's commercial

ties with Europe. For now, EU willingness to follow through on its promises and

threats regarding Ukraine depends on Russian maneuvers. European leaders, who

are divided because of the diverse set of constraints facing each member

country, are watching the Kremlin's moves closely.

Russia and the European Union have demonstrated that they each have

sufficient leverage to cause the other side significant grief, but both sides

have left themselves space to back down. As Crimea prepares for its March 16

referendum and the interim government in Kiev hopes to sign the political

aspects of its association agreement with the European Union the following

week, Moscow and Brussels are stalling on definitive actions. Neither side

wants to bear the costs of all the threats it has made, but both are keeping

their fingers on the trigger.

There also are the business

leaders in the Ukraine itself

The result is a political system in Ukraine that continues to depend

highly on the patronage and support of oligarchs. All major political parties

and candidates for powerful posts in parliament and the executive office have

their respective oligarch backers.

With presidential elections set for May 25 and parliamentary elections

likely to be held later in the year, Ukraine’s current administration will need

the continued support of the oligarchs. More immediately, with Crimea on the

verge of leaving Ukraine, the new government’s urgent challenge is to keep

mainland Ukraine together. Eastern Ukraine is crucial to this – the region is a

stronghold for pro-Russia sentiment and the main site of opposition, after

Crimea, to the Western-backed and Western-leaning government.

The oligarchs are key to keeping control over eastern Ukraine, not only

because Ukraine’s industrial production is concentrated in the east – thus

anchoring a shaky economy – but also because many of the oligarchs have a

stronger and more manageable relationship with Russia than the current

government, which Moscow sees as illegitimate. Many of these business leaders

hail from the industrial east. They have business ties to Russia and decades of

experience dealing with Russian authorities – experience that figures such as

Klitschko and Yatsenyuk lack.

So far, the new government has been able to maintain the support of the

country’s most important oligarchs. In general, the oligarchs want Ukraine to

stay united. They do not support partition or federalization, because this

would compromise their business interests across the country. But this support

is not guaranteed over the long term. There have been recent complaints about

the new government, for example over the arrest of former Kharkiv Gov. Mikhail

Dobkin. Akhmetov came out in Dobkin’s defense, saying the government should not

be going after internal rivals right now, but rather focusing on concerns over

Russia. This can be seen as a warning to the new administration: The oligarchs’

loyalty to the current regime is conditional and should not be taken for

granted.

Ultimately, the biggest threat to the oligarchs is not the current

government, over which they have substantial leverage, but Russia. The

oligarchs stand to lose a great deal if Russia intervenes in Eastern Ukraine.

If Russia takes over eastern territories, it could threaten the oligarchs’ very

control over their assets. Therefore they have an interest in bridging the gap

between Russia and Kiev, but it is Moscow they fear more. The oligarchs have

substantial power to shape the Ukrainian government’s decision-making as it

moves forward. Their business interests and the territorial integrity of the

country are at stake.

Russian-Western Conflict

Beyond Ukraine

A more worrying effect of the competition between the West and Russia

over Ukraine however extends beyond Ukrainian borders. As competition over the

fate of Ukraine has escalated, it has also intensified Western-Russian

competition elsewhere in the region.

Georgia and Moldova, two former Soviet countries that have sought

stronger ties with the West, have accelerated their attempts to further

integrate with the European Union -- and in Georgia's case, with NATO. On the

other hand, countries such as Belarus and Armenia have sought to strengthen

their economic and security ties with Russia. Countries already strongly

integrated with the West like the Baltics are glad to see Western powers stand

up to Russia, but meanwhile they know that they could be the next in line in

the struggle between Russia and the West. Russia could hit them economically,

and Moscow could also offer what it calls protection to their sizable Russian

minorities as it did in Crimea. Russia already has hinted at this in

discussions to extend Russian citizenship to ethnic Russians and Russian

speakers throughout the former Soviet Union.

The major question moving forward is how committed Russia and the West

are to backing and reinforcing their positions in these rival blocs. Russia has

made clear that it is willing to act militarily to defend its interests in

Ukraine. Russia showed the same level of dedication to preventing Georgia from

turning to NATO in 2008. Moscow has made no secret that it is willing to use a

mixture of economic pressure, energy manipulation and, if need be, military

force to prevent the countries on its periphery from leaving the Russian orbit.

In the meantime, Russia will seek to intensify integration efforts in its own

blocs, including the Customs Union on the economic side and the Collective

Security Treaty Organization on the military side.

So the big question is what the West intends. On several occasions, the

European Union and United States have proved that they can play a major role in

shaping events on the ground in Ukraine. Obtaining EU membership is a stated

goal of the governments in Moldova and Georgia, and a significant number of

people in Ukraine also support EU membership. But since it has yet to offer

sufficient aid or actual membership, the European Union has not demonstrated as

serious a commitment to the borderland countries as Russia has. It has

refrained from doing so for several reasons, including its own financial

troubles and political divisions and its dependence on energy and trade with

Russia. While the European Union may yet show stronger resolve as a result of

the current Ukrainian crisis, a major shift in the bloc's approach is unlikely

-- at least not on its own.

On the Western side, then, U.S. intentions are key. In recent years, the

United States has largely stayed on the sidelines in the competition over the

Russian periphery. The United States was just as quiet as the European Union

was in its reaction to the Russian invasion of Georgia, and calls leading up to

the invasion for swiftly integrating Ukraine and Georgia into NATO went largely

unanswered. Statements were made, but little was done.

But the global geopolitical climate has changed significantly since

2008. The United States is out of Iraq and is swiftly drawing down its forces

in Afghanistan. Washington is now acting more indirectly in the Middle East,

using a balance-of-power approach to pursue its interests in the region. This

frees up its foreign policy attention, which is significant, given that the

United States is the only party with the ability and resources to make a

serious push in the Russian periphery.

As the Ukraine crisis moves into the diplomatic realm, a major test of

U.S. willingness and ability to truly stand up to Russia is emerging.

Certainly, Washington has been quite vocal during the current Ukrainian crisis

and has shown signs of getting further involved elsewhere in the region, such

as in Poland and the Baltic states. But concrete action from the United States

with sufficient backing from the Europeans will be the true test of how

committed the West is to standing up to Moscow. Maneuvering around Ukraine's

deep divisions and Russian countermoves will be no easy task. But nothing short

of concerted efforts by a united Western front will suffice to pull Ukraine and

the rest of the borderlands toward the West.

Plus what about China?

China has, as usual, sat on the sidelines without getting even remotely

involved. And why should it? Neville Chamberlain’s description of conflict in

“a far away country between people of whom we know

nothing” was never more apt than in understanding China’s view of Eastern

Europe, which holds little in the way of natural resources and for the moment

does not represent a significant export market. True, the Chinese own 9 percent

of Ukrainian farmland now; but the crisis has probably been welcomed insofar as

it has relegated deeper analysis of the recent Kunming terrorist attack and the

broader Xinjiang problem to the back pages.

Yet China is mistaken to sit back and do nothing on Ukraine, because

there is something at stake. Strategically, Beijing may calculate that letting

the Americans become “involved” in the Ukraine means a further weakening of

Obama’s already rudderless efforts in the Pacific. But this is only half the

story: if this involvement went on to constitute a “defeat” (any scenario where

Russia ends up with a more secure border than before) it would help weaken the

strongest weapon in the U.S. arsenal: the soft power effect. This would further

dent belief across the world in the efficacy of American action, helping China

in its own Asian strategy. Moreover, China has no interest in helping

legitimize public protests as a form of sociopolitical reform and development.

In Kiev, just as in comparable situations such as Istanbul, Cairo and Bangkok,

there is an ongoing battle over the question of whether mass urban protest is

justifiable and productive, and how outside powers should intervene with

support or otherwise. China clearly is not incentivized to see the overthrow of

incumbent regimes.

There is also a longer term calculation. China is in many ways an

imperialistic power utilizing a “big country” approach towards diplomacy. It

has demonstrated a reluctance to engage in diplomacy as viewed through the

Westphalian paradigm, and its insensitivity constantly surprises Western

observers. But there is one issue which it cares deeply about: Taiwan. And the

Russian seizure of the Crimea provides an interesting template for China as to

how eventual reunification might take place in the “worst case” scenario,

namely through force. What the Russians have managed on their peninsula is to

act quickly and decisively, presenting the world with a fait accompli. It has

done so with very little violence, and through the mobilization of insiders

supportive to the region, whether or not they are in the majority, it can

present photogenic welcoming parties to the arriving forces. At the very least,

the situation is not (even in the Western media) a black-and-white case of

aggression. That is all that Russia needed; it is difficult to envisage any

outcome of the crisis now which does not see Russia with a strengthened

position in the Crimea, irrespective of what happens with the rest of the

Ukraine. A corresponding outcome with Taiwan would suit China nicely.

How could China insert itself in the Ukraine? It would be alarming for

Beijing to suddenly become a proactive player in a place so far away. Instead

China should be looking to leverage BRICS, or, if the relevant support from

India and Brazil are not forthcoming, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) as a vehicle to further its strategy.

China does not in fact care for multilateralism or these bodies per se; but it

is notionally signed up to them and they are as useful here as they will ever

be. Moreover, despite the general hubris that is an emerging feature of the

Chinese psyche in foreign policy, Russia is one of the few powers it has

historically respected. Thus, China can help Russia by driving a broader,

non-Western consensus to front this plan.

A possible deal needs to align a number of interests and satisfy some of

Russia’s key requirements whilst also allowing the West to claim the basis of a

new future. China would need to aim for the following:

The current Kiev administration must be ended and its actions

delegitimized. There is very little chance that Yanukovych can re-emerge but a

new interim government could feature regional representation – structured in

such a way that there is no question that the pro-Russian side has a voice

equal to its weight amongst the public. A new physical capital altogether may

even be advisable. What is paramount is that the government that arose out of

the protests in the square must be reduced in status to that of an illicit,

disruptive force.

The status of the Crimea is more problematic. It seems unclear that

Russia necessarily desired to occupy the region before the fear arose of losing

patronage over the Ukraine. The obvious solution is to strengthen its

“autonomy” and Russia’s military structures there, whilst maintaining the

notional integrity of the Ukraine overall. Russian seizure of the area

unilaterally – with or without the referendum – would be mutually exclusive to

point 1 and unlikely to be part of a SCO / BRICS-brokered deal.

Lastly there is the question of the Eastern Ukraine. In an extreme case,

Russia may want to press for plebiscites to decide its, future including

independence from Kiev and/or reunification with Russia. However plebiscites

would sit ill with China. A successful implementation of point 1 would negate

the need for Russia to push for voting and this could be supplemented by a

major commitment to BRICS-led investment in the eastern part of the country (as

opposed to US-led investment). This ‘federalization’ would serve China’s

interests in both protecting its current exposure and for it to be a further

base for expansion.

Such a plan could draw interest from a number of non-aligned parties.

The promise of economic development and investment is a powerful one, and one

could reasonably see entities such as Dubai becoming involved in making the

Eastern Ukraine some sort of regional “neutral” hub from which the BRICS+ can

establish themselves as a force.

It would require imagination, but there is far more to be gained for

China by attempting to do something, than by doing nothing. The latter offers

no long-term benefits, whilst the former could begin to add an interesting

arrow to the Chinese foreign relations quiver.

How will this unfold?

The Europeans do not feel as confident as Washington that losing Crimea

is worth an escalation in tensions or a complete break in relations with

Moscow, itself a significant partner. The European Union's priority continues

to be the management of its internal economic crisis. The more nuanced

political relationship European powers like Germany and France have with Moscow

makes it difficult for Brussels to match the aggressiveness of U.S. sanctions.

The rift between the interests of the United States and those of the

European Union is likely to widen as the standoff with Russia continues. This

particular round of sanctions will do little to sway Moscow's position

regarding Crimea, and the West has already threatened additional sanctions as

part of the ongoing negotiation process with Russia. However, it will be nearly

impossible for common ground to be found between the United States and Europe

on sanctions that carry real weight -- a division Moscow is sure to exploit to

its advantage as it tries to regain influence in mainland Ukraine.

For updates

click homepage here