By Eric

Vandenbroeck and co-workers

A Little

Imperium In Imperio

To know the context of what follows start with

the overview here, and for reference list of personalities

involved here.

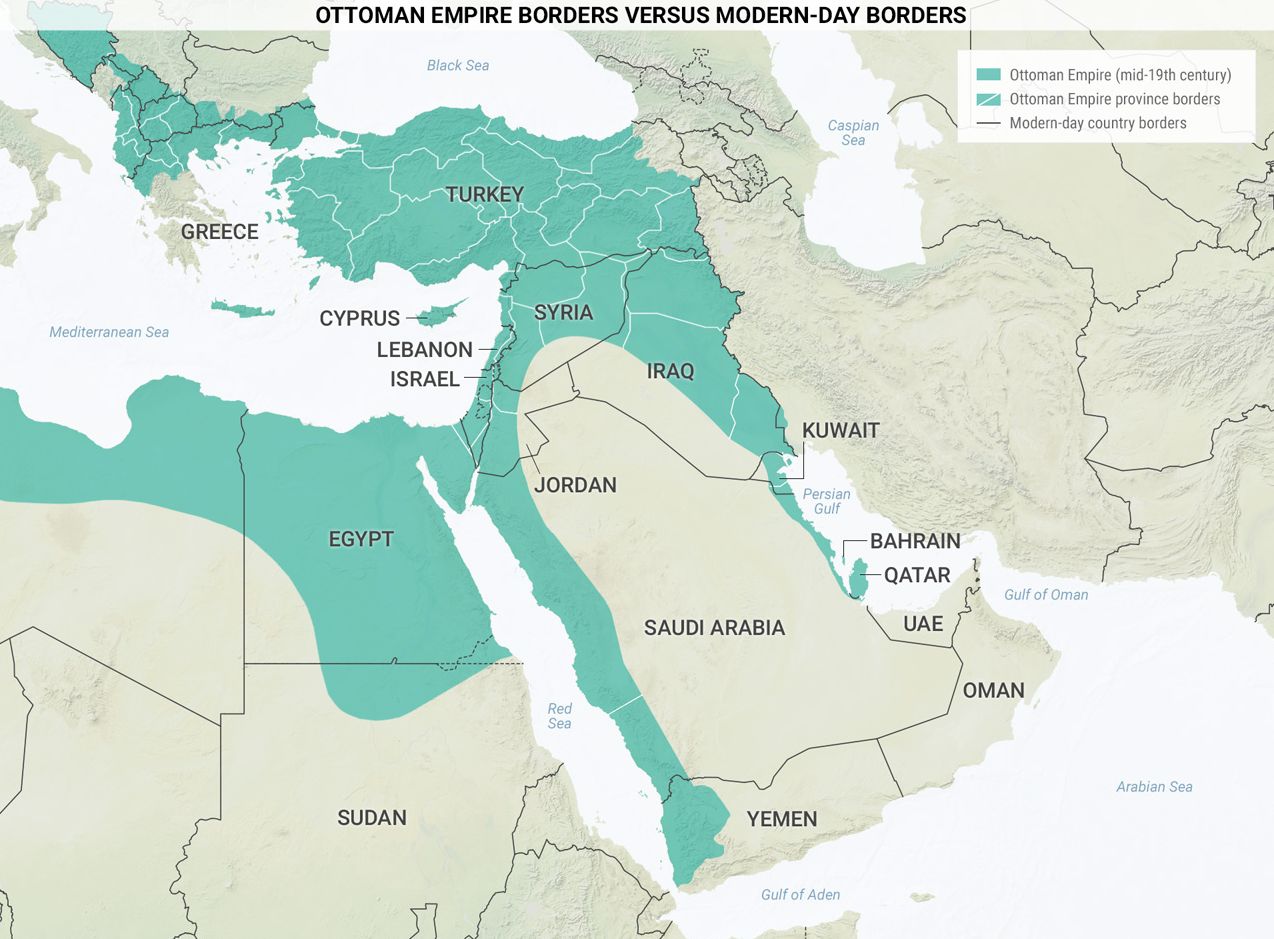

As we have seen the Sykes-Picot negotiations of 1916, had agreed to cede

most of greater Ottoman Syria to the French zone of influence, although only

the coastal area (i.e., today’s Lebanon) was supposed to be under direct French

rule, with the inland portions under 'independent' Arab administration, which

in practice meant Faisal and crowned ‘King’ Hussein’s

other sons. Theoretically, there was to be a kind of border between the two

zones stretching along a line drawn through Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo,

each allotted to the Arab side— though these cities were still squarely in the

French 'zone of influence.' But how was France to exert predominance over areas

now occupied by British troops? Complicating these questions further was the

Woodrow Wilson factor. Because of the possibly decisive contribution of

American troops to the collapse of German morale on the western front, along

with the financial leverage U.S. banking institutions now enjoyed vis-à-vis the

Allies indebted to them, the American president was believed to be nearly

all-powerful on the eve of the peace talks that would

open in Paris in January.

Starting in February 1917, and right up to the eve of the Paris peace

conference, the British attempted to cancel their agreement with the French.

In the early spring of 1918, Sir Percy Cox travelled to London for

consultations with the India Office and the Eastern Committee on the future of

Mesopotamia. He made a stopover in Egypt, where on 23 March a conference was

held at the Residency to discuss the situation between

Hussein and Ibn Sa’ud. Cox explained that ‘Ibn

Saud was exceedingly jealous and suspicious of King Hussein and he […] was

personally convinced that Ibn Saud would never acknowledge the King as his

temporal overlord, though he would always pay him, as he does now, the great respect

due to his religious position’. The conference agreed that ‘the Imam of Yemen,

Idrisi of Asir, and Ibn Saud were unlikely to accept King Hussein as their

temporal overlord’, but that this might change if Faisal’s forces were

successful in Syria, although admittedly ‘the inhabitants of Syria and

Mesopotamia were at one in their determination to allow no direct interference

in their affairs from the part of the King’. As far as British policy in

Central and South Arabia was concerned, little else could be done than ‘to keep

the peace between the different Amirs and to fulfil [our] treaty terms with

each’.¹

British policy towards the Arab chiefs remained one of not favoring any

one of them at the expense of the others, and preventing their jealousies and

rivalries escalating into open warfare. It was to be severely tested as a

result of what became known as the Khurma affair. On

9 July, Sir Reginald Wingate wired that ‘relations between King Hussein and Ibn

Saud are becoming increasingly strained and may lead to hostilities by their

respective adherents or even open rupture’. It was ‘not possible accurately to

appreciate various points at issue between them, but I think warning against

giving provocation addressed impartially to each would be salutary’. He

proposed a message in the following sense:

That His Majesty’s Government note with regret the ill-feeling between

King Hussein and Emir Ibn Saud as shown in their [?recent] correspondence and

regard it as seriously prejudicial to their interests and Arab cause. His

Majesty’s Government would view with great disfavour

any action by either party or their followers liable to aggravate situation or

to provoke hostilities.

In a further telegram Wingate warned that Hussein was greatly worried

about his position vis-à-vis Ibn Sa’ud and the other

Arab chiefs, and that ‘his present state of mind might lead him to a nervous

breakdown or ill- considered action’.²

Sykes was all in favor of making ‘the very strongest appeal’ to Hussein

and Ibn Sa’ud ‘to compose their differences and at

least agree to a truce for the duration of the war’, but he did not believe

that a crisis was at hand, since ‘the Arab mind always runs to negotiation and

compromise. It should not be impossible to get the two to appoint delegates to

meet on some neutral ground and there discuss the matter.’³

The Eastern Committee subsequently reformulated Wingate’s proposed

message so that it sounded less peremptory, and offered the British

government’s good offices ‘in coming to an agreement by negotiations’.⁴

The town of Khurma was situated some 120 miles

to the northeast of Taif, and in Aiteiba territory.

It had been part of Hussein’s domains, but the governor appointed by the king

had gone over to Ibn Sa’ud after a quarrel with

Abdullah. The situation escalated when Hussein decided to send troops to Khurma to reassert his authority. Although Hussein assured

Wilson that ‘matter is purely one of internal administration and that no

hostile action of any sort against Bin Saud is in- tended’, and that he

expected ‘to settle it without fighting’, Philby warned that it was ‘fairly

clear if expedition referred to materialises in Khurma the tension between Ibn Saud and Sharif, already

acute, will develop into open hostilities. It would seem desirable therefore to

request Sharif to defer action.’⁵

Given this danger, the Foreign Office decided to send a sterner message

to both chiefs. The British government could not ‘tolerate dissension between

their friends, and they must insist, on pain of their severe displeasure, that

neither party shall take any action likely to lead to open breach’. Hussein and

Ibn Sa’ud were also requested to send conciliatory

messages to one another, and to come to ‘amicable exchange of views with object

of arriving at settlement of outstanding differences’.⁶ After Cyril Wilson had

communicated this message to Hussein, it led to the kind of illconsidered

action Wingate had warned against. The king requested the British government

‘to accept his abdication as he feels he may be regarded as an obstacle to Arab

movement and an unwilling obstructor of His Majesty’s Government’s policy’.

According to Sir Reginald, Hussein considered ‘his scheme of unification as the

only satisfactory solution of Arabian question’. He also suspected the British

of ‘partiality to Bin Saud’, and insisted that ‘our attitude towards his action

at Khurma is an evidence of this. He would prefer to

re- sign now than to wait and see the collapse of his policy.’ Wingate

suggested sending a pacifying message to the king.⁷ The Foreign Office replied

the next day. Wilson was instructed to tell Hussein that the British government

could not:

Regard seriously a decision to abdicate […] under a mistaken impression

that Your Highness had lost the confidence of His Majesty’s Government […] far

from this being the case His Majesty’s Government regard your leadership of the

Arab movement in the war as vitally necessary for the Arab cause and can- not

think that Your Highness will withdraw at such a juncture.⁸

The same day, the India Office informed the viceroy and Cox that Khurma clearly fell ‘under King Husain’s sphere and outside

that in which intervention by Bin Saud is warranted. Philby should impress this

view of the case on Bin Saud.’ The Indian and Mesopotamian authorities should

realize that as far as Ibn Sa’ud was concerned

‘neither his services or commitments in the past, nor his potential utility in

the future, will bear any comparison with those of King Hussein’, and that

there- fore ‘we cannot allow latter’s interests to be prejudiced […] by

ill-timed activities of Bin Saud’.⁹

On 7 August, Arnold Wilson transmitted a report by Philby, in which the

latter explained that Ibn Sa’ud had little room for

maneuver in the question of Khurma. When he gave in

to Hussein, this might fatally weaken his position vis-à-vis his Ikhwan

warriors.¹⁰ Sir Reginald was receptive to Philby’s argument. Although Britain

must ‘uphold [Hussein’s] right to punish a rebel Sheikh’, and that ‘Mr Philby’s ready acquiescence in Bin Saud’s assertion that

King’s action is aggressive’ was ‘most regrettable and ill-advised’, at the

same time Wingate fully appreciated ‘necessity of returning friendship of Bin

Saud whom I understand represents strongest if not only Anglophile element in Nejdean politics’. He therefore agreed that Ibn Sa’ud ‘should be treated liberally in the matter of funds

which may also exercise a pacifying influence on hostile public opinion

referred to by Mr Philby’, but he also urged that

‘other sinews of war should not be supplied’.¹¹

Sir Reginald saw no other option to resolve the Khurma

dispute than ‘continuing representations to both parties that it is to their

common and individual interests to prevent outbreak of hostilities and by

trying to induce them to correspond (either direct or through us) with a view

to discovering a modus vivendi’.¹² The Foreign Office showed greater

creativity. On 28 August it suggested that ‘good might result if a meeting

between King Hussein and Ibn Saud could be arranged under careful management. A

discussion between them, held under our auspices and direction might clear the

air and facilitate a settlement.’ If these discussions were to fail, then at

least time would have been ‘gained, as both would be likely to remain quiescent

pending the meeting’. A ‘strong and impartial’ commission – consisting of

Philby, Lawrence or Cyril Wilson, with an impartial chairman − should prepare

and oversee the negotiations between the two chiefs.¹³ Wingate, however,

disapproved of the plan. Hardinge suggested that a meeting between Abdullah and

Ibn Sa’ud’s brother might be a viable alternative.

Cecil only regretted that Cairo failed to appreciate that the plan, ‘even if it

came to no result […] would hang up the controversy for the time being’.¹⁴

After Allenby’s rout of the Turkish forces at Megiddo (see ‘Allenby’s

Offensive and the Capture of Damascus’, below), and the rapid advance of his

troops to the north, Sykes hoped that the whole intractable question would sink

into oblivion. When Wingate reported on 23 September that Hussein had rejected

the proposed meeting between Abdullah and Ibn Sa’ud’s

brother, Sir Mark noted that ‘the great danger has hitherto been that under

stress of internal dissensions either the king would abdicate or Ibn Saud would

go over to the Turks. There are now no Turks to go over to, and if Medina

surrenders the King’s position will be much more stable […] In any event

central Arabian politics have returned to the normal condition of

unimportance.’¹⁵ A few weeks later, Sykes minuted

that the Arabian situation after Allenby’s victory had ‘subsided to its chronic

and normal unimportance’.¹⁶ However, the question simply would not go away. On

6 December, Wingate wired that the Ikhwan had attacked a Hashemite supply base

some 45 miles north of Taif, and that ‘a collision appears imminent’.¹⁷

Four days later, he reported that the Ikhwan were advancing further on

Hijaz territory. Sir Reginald therefore strongly recommended ‘immediate despatch by His Majesty’s Government of peremptory

instructions to Bin Saud to withdraw all militant Ikhwan from neighbourhood, making it clear to him that failure or delay

in compliance will entail reprisals’.¹⁸

On 23 December the Army Council made a startling proposal. In a letter

to the Foreign Office they explained that they were ‘doubtful whether this

matter can be settled by putting pressure on Ibn Saud personally, as the latter

may be unable to exercise control over the fanatical elements among his

subjects, many of whom regard his friendliness towards Europeans as unorthodox

and degenerate’. The Army Council therefore believed that ‘more open measures

are required to shew Arabia definitely that the policy of His Majesty’s

Government is to support King Hussein, against all aggression’. If the foreign

secretary concurred, they were prepared to dispatch ‘immediately to Mecca, such

equipment as the Sherif may ask for and be able to use, as well as a suitable

force of Mohamedan troops’.

Shades of Rabegh, although not for Sir Eyre

Crowe, who proposed to concur, and the India Office was so informed

immediately.¹⁹ The India Office also appeared to have no recollection of the Rabegh crisis. It saw

‘no objection to the proposals of the War Office’. George Kidston of the

Foreign Office had, however, asked Lawrence for his opinion, and the latter was

very much against it. He used the same argument that had been so effective in

killing the plans to send a brigade to Rabegh in the

autumn of 1916, namely that the deployment of British troops in the Hijaz would

fatally discredit Hussein in the eyes of the Arabs. It would be ‘regarded as

the crowning phase of the policy of which we are accused in hostile Moslem

circles in Asia – the gradual reduction of Mecca to the status of a British

protectorate’. In view of Lawrence’s objections, Kidston thought that it was

‘difficult to act as proposed […] The only thing, therefore, that we can do is

to warn the War Office of the danger of offering Hussein Mahommedan troops for

Mecca.’ It was not until 10 January 1919 that the Foreign Office informed the

Army Council that, ‘after full consideration’, it was ‘averse from the proposal

to despatch Mohammedan troops to Mecca, since such a

step might be made use of by unfriendly persons to spread in Moslem circles the

impression that the policy of His Majesty’s Government with respect to the Arab

State implies undue interference in the holy places of Islam’.²⁰ That same day,

the garrison of Medina finally surrendered to the Hashemite forces. In view of

this development, so Montagu wired to Arnold Wilson on 16 January, ‘nothing is

to be gained by further intervention in dispute between King Hussein and Bin

Saud’.²¹

Mitigating or Abolishing the

Sykes–Picot Agreement

The very first attempt to persuade the French that the terms of the

Sykes–Picot agreement should be reconsidered was made by Sykes. On 28 February

1917, he explained to Georges-Picot that an international administration for

the ‘brown area’ – as laid down in article 3 of the agreement – would

‘inevitably drift into a condition of chaos and dissension’. It would be far

better if Palestine should become an American protectorate. Picot, however,

refused to consider this alternative. Prime Minister Lloyd George was very much

in favor of a British protectorate, but at the conference of Saint Jean-de-Maurienne his hints in this direction ‘had been very coldly

received’ by the French and the Italians. When the War Cabinet reviewed the

results of the conference on 25 April 1917, they therefore concluded that

although they ‘inclined to the view that sooner or later the Sykes–Picot

Agreement might have to be reconsidered […] No action should at present be

taken in this matter.’²²

David Hogarth was in London at the beginning of July 1917. He drew up a

memorandum in which he advocated ‘some reconsideration of the Agreement’. He

claimed that it had favored France, but presumed that there must have been

‘sufficient reasons of general policy […] to so favour

France’. These, however, appeared no longer to apply, especially because ‘the

position of one beneficiary – ourselves – has been very greatly strengthened

both by the part we have played among the Arabs in the Hejaz and in Mesopotamia,

and by the open and insistent preference declared by the Zionist Jews’, while

at the same time ‘a strong and increasing feeling has manifested itself in

opposition to French penetration of any part of the Arab area’.²³ Even though

Hogarth observed to Clayton that in London he had ‘found no one who both takes

the S.P. Agreement seriously and approves of it – except M.S. himself’,²⁴ Sykes

could cheerfully report to Clayton some two weeks later that Hogarth ‘got

trounced by the Foreign Office for meddling in affairs without consulting

proper authorities, he being an Admiralty employee. This departmentalism for

once served my ends.’²⁵

On 13 July, Harold Nicolson completed a memorandum, written at the

request of Balfour, on British ‘contractual’ and ‘moral’ obligations towards

Russia, France, Italy and the Sherif of Mecca with respect to the territory of

the Ottoman Empire. Nicolson’s observations on the Sykes–Picot agreement made

Sir Mark produce a memorandum of his own, in which he sub- mitted that Nicolson

had not attributed ‘sufficient importance to the moral side of the question and

to the ideals for which the best elements in this war are fighting, viz: the

liberation of oppressed peoples and the maintenance of world peace’. Sykes

admitted that the Sykes–Picot agreement allowed the signatory states to annex

certain areas, but claimed that ‘formal annexation’ was ‘quite contrary to the

spirit of the time, and would only lay up a store of future trouble’. Two

central axioms should guide British action in the Middle East. One was the

‘unalterable friendship of Great Britain and France’, the other ‘the duty of

Great Britain and France towards oppressed peoples’. It was Sykes’s firm belief

that if ‘Great Britain and France stick to these two grand principles then we

may gain our temporal requirements without endangering our good name or running

counter to the ethical sense of mankind as a whole’. What was needed was a

‘frank discussion between the British and French governments’, in which it was

‘essential’ to get the French to ‘play up to Arab nationalism with loyalty and

purpose, and give definite instructions to their local officers to act

accordingly’. Sir Mark also reminded his colleagues that France was ‘a better neighbour than Turkey or Germany’, and that (in a clear

snipe at Hogarth) ‘no petty consideration that France is getting more than her

share should stand between Great Britain and the beating of the enemy’.²⁶

In a further memorandum Sykes reiterated that the frank discussion

between the allies should concentrate on ‘the attitude they intend to adopt

towards the populations inhabiting those regions’. First of all, the avenue

that had been ‘left open to annexation’ had to be closed off. Annexation was

‘contrary to the spirit of the time, and if at any moment the Russian

extremists got hold of a copy they could make much capital against the whole

entente’. France and Britain should come to an agreement ‘not to annex but to

administer the country in consonance with the ascertained wishes of the people

and to include the blue and red areas in the areas A and B’. If France boldly

came out ‘with a recognition of […] Arab nationality in Syria as a whole they

would sacrifice nothing and gain much’. With respect to Palestine, France

should agree that Britain was ‘appointed trustee of the Powers for the

administration’ of the country. Naturally, this would ‘be very objectionable to

the French, but they really must be induced to settle matters up in their own

interest’. They also should accept that Syria and the Lebanon became autonomous

states, ‘under French patronage, but under a national flag’. If the French

would ‘not agree to such a joint policy’, then Britain should abide by the

agreement, but then it would be for the French ‘to make good – that is to say

that if they cannot make a military effort compatible with their policy they

should modify their policy’.

George Clerk was rather taken aback by the boldness of Sykes’s

proposals. He noted that ‘the conclusion of this paper seems to be that, having

got the Sykes–Picot Agreement […] we are to propose scrapping the whole thing.

“Since I am so early done for, I wonder what I was begun for!”’ He also

observed that a policy of no annexation would ‘make Basra rather a problem’.

Although some of Sir Mark’s proposals were ‘excellent’, ‘desirable’, or

‘possibly salutary’ they would not ‘enhance our popularity’. Sir Ronald Graham

agreed that, ‘with the possible exception of Basrah, it is preferable for us to

“protect” or “influence” rather than formally annex. But it is a delicate

matter to approach the French […] on the subject and we are likely to be

misunderstood.’ He suggested that Georges-Picot, ‘who is now over here and will

go further in the direction pro- posed than any other Frenchman I know of,

should be consulted’. Balfour, however, rejected Graham’s suggestion. Until the

War Cabinet had considered the matter there was ‘little use in interesting

Picot’.²⁷

At Sykes’s request, his memorandum was circulated to the War Cabinet,

but was not put on the agenda. At the end of September 1917, Clayton

nevertheless felt confident enough to reassure Lawrence – who had written a

violently anti-French, anti-agreement letter to Sykes that Clayton thought

inadvisable to send on²⁸ – that from all he had heard:

The S–P agreement is in considerable disfavour

in most quarters […] The change in the Russian situation has wounded it

severely and the general orientation of Allied policy towards ‘no annexations’,

‘no indemnities, etc.’, militates still further against many of its provisions.

I am inclined, therefore, to think that it is moribund. At the same time we are

pledged in honour to France to give it the

‘coup-de-grace’ and must for the present act loyally up to it, in so far as we

can. The S–P agreement was made nearly two years ago. The world has moved at so

vastly increased a pace since then that it is now as old and out of date as the

battle of Waterloo or the death of Queen Anne. It is in fact dead and, if we

wait quietly, this fact will soon be realised. It was

never a very workable instrument and is now al- most a lifeless monument. At

the same time we cannot expect the French to see this yet, and we must

therefore play up to it as loyally as possible until force of circumstance

brings it home to them.²⁹

A further impetus to the idea that the Sykes–Picot agreement was

obsolete and could not stand was provided by a flurry of declarations and

speeches on war aims by, respectively, the Bolsheviks, the Central Powers,

Prime Minister Lloyd George and President Wilson in the last weeks of December

1917 and the first of January 1918. On 22 November 1917, Leon Trotsky,

commissary of foreign affairs, had addressed a note to the ambassadors at

Petrograd ‘containing proposals for a truce and a democratic peace without

annexation and without indemnities, based on the principle of the independence

of nations, and of their right to determine the nature of their own development

themselves’.³⁰ Peace negotiations with the Quadruple Alliance – Germany,

Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey – started at Brest- Litovsk one month

later. During the opening session of the conference, the Russian delegation

read out a declaration on the six principles on the basis of which the

negotiations should be conducted. The third of these stated that national

groups that had not been independent before the war should be ‘guaranteed the

possibility of deciding by referendum the question of belonging to one State or

another, or enjoying their political independence’, and the fourth that minorities

should have the right to an autonomous administration. On behalf of the

Quadruple Alliance, the Austrian minister for foreign affairs, Count Czernin, replied on 25 December. The Russian principles

formed ‘a discussible basis […] for peace’. With respect to principles three

and four, Czernin declared that the ‘question of

State allegiance of national groups which possess no State independence’ should

be solved by ‘every State with its peoples independently in a constitutional

manner’, and that ‘the right of minorities forms an essential component part of

the constitutional right of peoples to self- determination’.³¹

Lloyd George and other members of the War Cabinet felt that Czernin’s speech could not be left unanswered. At the end

of December and during the first days of January there were a series of

discussions on the contents of a British declaration on war aims. At a meeting

of the War Cabinet on 3 January, the Prime Minister expressed his willingness

‘to accept the application of the principle of self-determination to the

captured German colonies […] Mesopotamia […] and […] Palestine’.³² In the final

version of Lloyd George’s speech, which he delivered on 5 January, there were

several references to the right of self-determination. The most important was

that a ‘permanent peace’ could only be secured through a territorial settlement

‘based on the right of self-determination or the consent of the governed’. With

respect to the non-Turkish parts of the Ottoman Empire, the Prime Minister

scoffed at Czernin’s third principle, which implied

that ‘the form of self- government […] to be given to Arabs, Armenians, or

Syrians is […] entirely a matter for the Sublime Porte’. The British government

for their part were agreed that ‘Arabia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Syria, and

Palestine are […] entitled to a recognition of their separate national

conditions’, but ‘what the exact form of that recognition in each particular

case should be need not here be discussed, beyond stating that it would be

impossible to restore to their former sovereignty the territories to which I

have already referred’. Lloyd George could not deny that much had recently

‘been said about the arrangements we have entered into with our Allies on this

and on other subjects’, but that the conditions under which these had been made

had changed, and he expressed his readiness ‘to discuss them with our

Allies’.³³

Enter President Wilson

Three days later it was President Wilson’s turn to answer Czernin’s challenge. In a speech to a joint session of the

American Congress he stated that:

What we demand in this war, therefore, is nothing peculiar to ourselves.

It is that the world be made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it

be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live

its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair

dealing by the other peoples of the world, as against force and selfish

aggression.

Wilson subsequently enumerated the 14 points on which ‘the program of

the world’s peace must be based’. The 12th of these was that ‘the Turkish

portions of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty,

but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured

an un- doubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of

autonomous development’. The President did not explicitly invoke the principle

of self- determination, but in a further speech to Congress on 11 February,

Wilson observed that ‘self-determination is not a mere phrase. It is an

imperative principle of action which statesmen will henceforth ignore at their

own peril.’³⁴

Predictably, Sykes was the first to recognize the implications of these

declarations and speeches for the Sykes–Picot agreement. He minuted

on 16 February that ‘the Anglo–French Agreement of 1916 in regard to Asia Minor

should come up for reconsideration’, and deplored that ministers were placed

‘under the necessity of having to uphold agreements which are out of harmony

with the expressed policy of the Entente and the United States, and which are

based on a state of affairs which no longer exists’. Hardinge, also rather

predictably, disagreed. He warned that ‘to do this would only open the door to

further discussion with the French and Italians, and unless it be necessary

from a Parliamentary point of view I would deprecate such action’.³⁵

Sykes wrote to Clayton on 3 March 1918 that ‘ever since Kerensky’s

disappearance’, he had regarded the agreements ‘as completely worn out and that

they should be scrapped. When they were made the United States of America was

not in the war, Russia existed and the Italians had not been defeated.’ He

claimed that ‘for the time at which it was made the Agreement was conceived on

liberal lines’, but admitted that ‘the world has marched so far since then that

the Agreement can only be considered a reactionary measure […] the stipulations

in regard to the red and blue areas can only be regarded as quite contrary to

the spirit of every ministerial speech that has been made for the last three

months.’ He enclosed a letter to Georges-Picot in the same vein, and observed

that he ‘should be very glad if you would talk this matter over with Monsieur

Picot. I do not think he quite realises how far

things have gone or how little interest outside a very narrow circle in France

people take in the question of Syria and Palestine.’³⁶

Clayton was simply delighted. On 4 April he replied that Sykes’s ‘clear

statement of the state of affairs in regard to this question’ had helped him

‘greatly’. He confessed that he had always felt this way, but until the receipt

of Sir Mark’s letter he ‘had not been quite sure that H.M.G. had come to a

definite decision in the matter’. He presumed that the French government had

not yet been informed of it, as he saw ‘no sign from Picot that he has any idea

that such a policy is in contemplation and he still regards the agreements as

his bible’. Clayton assured Sykes that he would ‘take an early opportunity of

discussing the whole question with him and sounding him on those lines,

probably giving it as my own personal opinion that the agreements are out of date,

reactionary, and only fit for the scrap heap’.³⁷ He reported this conversation

to Balfour on 19 May 1918. He had intimated to Picot ‘my opinion that the

Sykes–Picot agreement, if not absolutely dead, is at any rate an impracticable

instrument as it stands’. The latter had ‘allowed that considerable revision

was required in view of changes that had taken place in the situation since

agreement was drawn up’, but nevertheless considered that ‘agreement holds, at

any rate principle’.³⁸

At the beginning of April, on the

eve of Sir Percy Cox’s visit to London, the India Office wrestled with the

implications of ‘the spread of the doctrine of “self- determination” under the

powerful advocacy of the President of the United States’ for the future status

of Mesopotamia. It was not suggested that the government’s policy ‘should be

modified in essence’, as it was ‘scarcely thinkable that we should suffer the

results already achieved to be entirely thrown away’, but one could not ignore

‘the general change of outlook […] which the war has brought about’. The India

Office therefore proposed to ask Cox ‘what elements in the population is it

specially desirable to strengthen and encourage, with a view of ensuring that,

if and when the moment for “self-determination” arises, there will be a

decisive pronouncement in favour of continuing the

British connection?’ Sir Percy for his part was not disturbed by the principle

that ‘the peoples of the countries interested or affected should be allowed to

deter- mine their own form of government’. He assumed that ‘if at the end of

the war we find ourselves in a sufficiently strong position, and in effective

administrative control, we should still hope to annex the Basrah Vilayet and

exercise a veiled protectorate over the Baghdad Vi- layet’.

At the same time he recognized that ‘the question of annexation has become

exceedingly difficult vis-à-vis the President of the United States, who will

presumably exercise the most potent influence at the Peace Conference. Our original

proposals must consequently be regarded as a counsel of perfection, and we must

be prepared to accept something less.’ A policy of an ‘Arab façade’ should

offer ‘no insurmountable difficulties’.

Sykes was shocked by Cox’s adaptation of the principle of

self-determination to the Mesopotamian situation. He angrily noted:

We should come to a clear decision as to what is the basis of our

Mesopotamian policy. Is it to be camouflaged Imperialism or is it a policy of

development with Democratic and World objectives? I have always objected to the

expression Arab Façade as typifying an out-of-date point of view.

He urged the Eastern Committee not to take Egypt or India as models, as

in ‘both places our basis of occupation is Imperialistic, and in both places we

are going to be confronted with revolutionary democratic movements which will

probably have the support of the future governments of this country when the

re-action comes after the war’. These difficulties could only be avoided ‘if

our policy is logical and public and does not conceal a second policy of hidden

annexation and ascendancy’.³⁹ Sir Mark, however, got nowhere at the meeting of

the Eastern Committee where the question was discussed in his presence and

Cox’s on 24 April 1918. Although Curzon agreed that British policy ‘might have

to be adapted to certain formulae, such as that of “self-determination,”

increasingly used as a watchword since President Wilson’s entry into the war’,

that was as far as he was prepared to go. In Mesopotamia ‘we should construct a

State with an “Arab Façade”, ruled and administered under British guidance’,

and where Basra was concerned, ‘it might be desirable to keep Basra town and

district entirely in British hands’. Balfour believed that:

President Wilson did not seriously mean to apply his formula outside

Europe. He meant that no ‘civilised’ communities

should remain under the heel of other ‘civilised’

communities: as to politically inarticulate peoples, he would probably not say

more than that their true interests should prevail as against exploitation by

conquerors. If so, an Arab State under British protection would satisfy him

(and with him the American public, though less enlightened), if it were shown

that the Arabs could not stand alone. Doubtless the Arabs, if offered the

choice, would choose what we wished. He

therefore thought it ‘unlikely that President Wilson would oppose the policy

suggested’. After Curzon had expressed the hope that ‘should the word

“annexation” appear too inauspicious (as suggested by Sir Mark Sykes) […] a

terminological variant, such as “perpetual lease,” or “enclave,” might be

found, both to safeguard the reality which we must not abandon, and to save the

appearances which the occasion might require’, the Eastern Committee ‘approved

Sir P. Cox’s Memorandum, and desired him to proceed with the development of the

administration in Mesopotamia on the lines that had been laid down’.⁴⁰

During their conference at the beginning of July 1918, Sykes and Picot

also discussed the situation with respect to the agreement. Sykes repeated once

more his argument that it ‘had been profoundly affected by the exit of Russia,

the entrance of the United States and the accentuation of the Democratic nature

of allied War Aims in general’. Picot countered by explaining that ‘the

Agreement could not be abolished, as such an act would raise violent opposition

and ill feeling among the Colonials in France, and would give great strength to

the financial pro-Turkish elements both of which would be most fatal

developments, and helpful to the enemy’. After ‘some discussion and careful

examination’, they drew up two papers. The first of these was a proposal for a joint

declaration to the King of the Hijaz. The second, paper B, concerned a

statement of Anglo–French war aims in the Middle East:

1. In the opinion of the governments of Great Britain and France there

can be no prospect of a permanent and lasting peace in the Middle East so long

as non-Ottoman nationalities, now subject to Ottoman rule, or inhabiting areas

hitherto subject to Ottoman rule now occupied by the Allied forces, have no

adequate guarantee of social, material, and political security.

2. That the only guarantee of permanent improvement is to be found in

the securing of self- government to the inhabitants of such areas.

3. That in view of the condition of these areas arising from

misgovernment, devastation, and massacre, it is the opinion of the two Powers,

that a period of tutelage must supervene before the inhabitants of the areas

are capable of complete self-government, and in a position to maintain their

independence.

4. That the Powers exercising such tutelage should exercise it on the

sanction of the free nations of the world, and with the consent of the

inhabitants of the areas concerned.⁴¹

Paper B was coolly received in the Foreign Office. Sir Eric Drummond

doubted ‘very much the wisdom of B. I do not think we ought to bind ourselves

definitely to the principles laid down in paragraphs 3 and 4’, and Hardinge was

‘very doubtful as to the value of such declarations. We have already made

several […] and they may, as has often happened in the past, prove inconvenient

in the future.’⁴²

Paper B was to be discussed at the Eastern Committee’s meeting of 15

July, but on Sykes’s request the discussion was adjourned. At the next meeting,

discussion was again postponed at his request, this time, as it turned out, for

good.⁴³ The idea that it was desirable to publish an Anglo–French declaration

on war aims in the Middle East had, however, set. On 6 August, Cecil told the

Italian ambassador that ‘there was considerable anxiety in Arab circles lest we

should be going to annex districts which were populated by Arabs, and it was

partly to allay these anxieties that we were considering whether we should

formally propose to the French government some declaration of this kind’.⁴⁴ At

the Eastern Committee’s meeting of 8 August, Cecil moreover emphasized that the

point of such a declaration ‘was to ensure beforehand that the French if and

when we entered Syria, should not make use of our military forces in order to

carry out a policy which was at variance with our general engagements’.⁴⁵

The next day, Hogarth submitted a memorandum on the Arab question to the

Foreign Office in which he again pressed home the point that:

The belief, amounting, since Bolshevik revelations, to certainty, that

we have pledged great part of Syria to France, for her occupation or her

exclusive influence, is the greatest stumbling-block we have to encounter […]

Outside a small denationalised minority, which

however is more articulate than the majority, the feeling of all classes of

Syrians against entry into the French colonial sphere is of the strongest and

most irreconcilable sort.⁴⁶

Hogarth’s memorandum led to an interview with Lord Robert on 17 August.

The next day, Hogarth submitted the draft of an Anglo–French declaration to the

King of the Hijaz, as an alternative to the one proposed by Sykes and Picot.

Cecil heavily edited Hogarth’s draft, which resulted in the following text:

Great Britain and France undertake severally and jointly to promote and

assist the establishment of native governments and administrations in all parts

of the Arab-speaking areas of Arabia, Syria, Jazirah and Upper Iraq, and to recognise them as effectively established. Further, they

pledge them- selves, after the areas have been liberated from the Turks, not to

annex any part of them, provided they be not invited expressly to do so by the

majority of the inhabitants or by the native government of any of such areas,

unless the native governments should become unable or unwilling to prevent

annexation, protection, or occupation by any other foreign power.

George Lloyd was also invited to give his views on a joint Anglo–French

declaration. He observed that it was ‘generally agreed that in view of what has

occurred since’, the Sykes–Picot agreement was ‘a source of embarrassment at

the moment’, but rather doubted the wisdom of making yet another declaration,

especially considering that ‘America may well be in a position to disturb and

perhaps break any agreements we now make, and if this occurred we should suffer

serious damage in regard to Eastern confidence in our under- takings’. He

therefore advised that ‘fresh declarations made by ourselves and France to the

Arabs or made between France and ourselves about the Arabs are undesirable if

they can by any means be avoided’. However, in case it was decided that a

declaration could not be avoided, then it should be ‘clearly understood that it

is not made as a rider or an addendum to the Sykes–Picot agreement, but in

definite substitution of it and of all those agreements with Italy or others

that resulted from it’. Cecil quite agreed, but lamented ‘how are we to

mitigate or abolish the S.P. agreement? It is I fear impossible to induce the

French to agree to its abrogation.’⁴⁷

On 4 September 1918, the French Embassy reminded the Foreign Office of

its demarche of 1 August on the administration of occupied enemy territory in

the French sphere of influence (see ‘French Participation in the Administration

of Palestine’). Sykes minuted that the best thing was

to ask Georges-Picot ‘to come over here and put the matter on a settled basis’.

He still adhered to his ‘original idea that we should do two things together.

(A) In return for arrangements as to French position west of Syria being

occupied by us, get (B) French statement as to the policy they would follow.’⁴⁸

A few days later, Sykes received a letter from Picot complaining that ‘the

embassy has several times demanded a reply to its demarches on the

administration of the territories in our zone; but failed to get one’, and

warning that in France ‘people do not understand this silence at all; malicious

spirits see hidden intentions, others are worried. As far as I am concerned, I

cannot return before the question is settled and the prolongation of my stay

threatens every day to lead to a scandal.’

In his reply, Sir Mark almost pleaded with Picot that France should

relent and at last acknowledge ‘the spirit of the age’. If French colonialists

insisted on ‘supporting an annexationist policy’, then ‘disaster alone’ could

ensue. France really had no other option than ‘to come out with a declaration

supporting Syrian and Lebanese independence on national lines. To say that

France is ready to give all assistance and protection to Syria, but does not

desire to impose institutions on the country, nor to insist on an unsolicited

occupation thereof after the war.’ Sykes threatened that even he, France’s last

champion in England, was thinking of giving up on her, and ended his letter on

a note of exasperation:

My point is this, getting France to make a concession in policy is like

getting blood out of a stone. I don’t ask you to modify the area of your

interest, but the extent of it […] Just as Syrians ask me for a single proof

that France means to do other than back minorities, annex Blue Syria, and paralyse the hinterland, so British people ask me for a

single proof that Syria is going to be developed on other than ordinary French

colonial lines, and any real indication that anything else is to be expected.⁴⁹

‘a little imperium in imperio’

Cecil chafed under the Eastern Committee’s dominant position in the

formulation of Middle East policy. He very much resented the Committee’s, and

especially its chairman’s, constant meddling in matters he firmly believed to

be the preserve of the Foreign Office. The day- to-day execution of Middle East

policy should be in the hands of his department. The Eastern Committee should

limit itself to discussing matters of high policy and to arbitrate and

coordinate when the policies pursued by the departments concerned − the India

Office, the War Office, the Foreign Office and, occasionally, the Treasury –

threatened to come into conflict. In the middle of July 1918, Cecil’s chances

to push through this vision appeared to be greatly increased by his appointment

as assistant secretary of state for foreign affairs – a constitutional novelty

– with special responsibility for, among other subjects, the Middle East (he

continued as parliamentary under-secretary for foreign affairs).

From a memorandum Montagu had submitted on 5 July, it appeared that he

thought on the same lines as Cecil. He was sure that action had ‘been delayed

by the necessity for awaiting decisions of the Eastern Committee’. The

committee ‘should not attempt actual executive action, but […] should be a

Cabinet Committee, discussing, on behalf of the Cabinet, Cabinet matters,

questions of policy, leaving details of the conduct of the policy to the

Departments concerned’. Montagu also suggested the establishment of a sub-committee

of three, ‘consisting of an Under-Secretary of State or an Assistant

Under-Secretary of State from the Foreign Office and from the India Office,

with the Director of Military Intelligence from the War Office’. This sub-

committee would then have the duty ‘to thresh out everything, and to give

decisions except on matters of high policy or of such great importance as

should go before the Ministers of the Committee for decision’.

Sir Henry Wilson also chimed in. The CIGS claimed that ‘Mr Montagu’s statement that the present organisation

inevitably leads to action being frequently delayed cannot be disputed’. Action

was not only ‘delayed owing to the necessity of obtaining the sanction of the

Committee to every step taken in the execution of policy already laid down by

the Committee’, but also ‘a ruling as to important questions of policy has on

several occasions been postponed from one meeting to another owing to the fact

that the Committee is overburdened with executive action’. The War Office

therefore were ‘in general accord’ with the changes ‘of great importance’

suggested by Montagu.

Cecil naturally could not but agree. He noted on 20 July that ‘for

executive purposes the Eastern Committee is not a convenient instrument. It

necessarily meets comparatively seldom, and even so is a great burden on the

time of the very busy men who constitute the Committee.’ Executive matters

therefore should be dealt with, ‘as far as possible […] either by the

individual departments immediately concerned or by informal consultations

between two or more departments, and I trust that this system will be increasingly

adopted in the future’. Only in important matters ‘the Chairman of the

Committee should be consulted just as the Prime Minister is, or ought to be’.

The Foreign Office, however, did not speak with one voice. On 17 July

the department had circulated its own note on the subject, which was far less

critical of the Eastern Committee. It admitted that ‘action in important

matters meets occasionally with some delay’, and agreed that ‘a considerable

number of questions of secondary

importance relating to the situation in the East which are now submitted to the

Committee are capable of inter-departmental adjustment without re- course to

the Committee’, but on the whole it could ‘hardly be denied that the Eastern

Committee in its present form has proved a very useful branch of the War

Cabinet’, and it was ‘doubtful whether the conduct of affairs now under the

control of the Committee would either in the present or the future be improved

by any material change in its present form of organisation’.

Ten days later, Balfour sided with the department. He, too, thought that the

critics of the Eastern Committee ‘exaggerate its shortcomings’. Balfour

moreover completely turned around Montagu’s suggestion to set up a small

sub-committee that would deal with day-to-day affairs. Instead of the

sub-committee deciding which matters should be sent up to the Eastern

Committee, it should be Curzon as chairman deciding which questions could be

handled by the sub-committee.

Curzon therefore had an easy time in parrying the three-pronged attack

by Montagu, Wilson and Cecil. In a memorandum, dated 1 August, he declared that

he was not ‘aware of any question of importance, the decision of which has been

delayed by the procedure or constitution of the Committee’. Certainly there had

been delays, ‘as, for instance, the discussion of the present subject’, but

these had been caused not by the Committee, ‘but by the slowness of the

departments in submitting their views’. Curzon added that:

In practice the departmental devolution that is recommended in some of

these papers already exists […] Action is taken upon the great majority of the

telegrams that come in both to Foreign Office, India Office, and War Office,

without any reference to the Committee (or, I may add, to the Chairman) at all.

The Departments have found no difficulty in discriminating between what I may

call departmental cases and Committee cases.

He also saw ‘no reason for the constitution of a Sub- Committee, with

powers either of decision or action’. He could only ‘concur in Mr Balfour’s view that we are dealing not unsuccessfully

with a complex situation, and that for the present no substantial changes are

required’.⁵⁰

Curzon was not allowed to savor his moment of triumph for very long. He

had ‘only just completed [his] note on Montagu’s proposals’ when he received a

letter from Cecil in which the latter announced his intention, ‘unless you see

some objection’, to ask ‘Oliphant, Shuckburgh, and Macdonogh

to meet frequently, so that all routine matters arising out of the Persian and

Middle East telegrams and involving more than one of the offices can be rapidly

disposed of without interdepartmental correspondence’. These officials would

meet in Cecil’s room ‘two or three times a week, or oftener if necessary, and

then I could see that they did not dispose of any really important matter

without consulting you, or if necessary the Eastern Committee’. Curzon replied

right away. He was shocked that Cecil ‘without waiting for any decision’

contemplated setting up this committee, and viewed this move ‘with considerable

suspicion’. The committee would ‘almost certainly develop into a little

imperium in imperio, whose tendency will be to act on

his own account, and to usurp the powers of the Eastern Committee’. Curzon

therefore hoped that ‘after this explanation […] you will not think it

necessary to pursue the idea’. Lord Robert hastily assured Curzon the same day

that ‘of course no meeting of the kind to which you object shall take place,

pending a discussion of the whole matter by the Eastern Com- mittee’.⁵¹

The discussion on the Eastern Committee and its functions finally took

place on 13 August 1918. Montagu, Cecil and Curzon extensively rehearsed their

arguments. At the end of the discussion, Curzon found it necessary to warn

that, if the Eastern Committee would overrule him and approve the establishment

of ‘a formal sub- committee’, then he would have ‘to ask to be relieved of his

present duties’. General Smuts came to his rescue. He had been ‘much impressed

with the case made out by the Chairman, who had, it was universally admitted

exceptional qualifications for his present position as President of their

Committee. It would be a very serious matter to set up a smaller body which

might encroach upon the functions of the Committee.’ He moreover opined that

the Eastern Committee was not free to decide this matter; ‘if any considerable

change were con- templated he thought the matter would have to go before the

Cabinet’.⁵²

Even though Curzon visited Hankey one week later ‘to explain to me his

difficulties with Montagu and Lord R. Cecil at the Eastern Committee’,⁵³ this

was more or less where the affair ended, also because Montagu decided not to

pursue the matter any further. As he explained in a letter to Cecil, he had

found that ‘you, and I noticed at dinner Eric [Sir Eric Drummond], are not a

little inclined to consider my desire to get a better form of administration in

Eastern matters as being personal in their application to Lord Curzon’. This

was ‘so inaccurate and has caused me such deep concern, that I propose to

abandon the matter and to acquiesce, rather than to be further misunderstood

[…] I therefore propose to drop the subject and shall inform Lord Curzon of this

decision when he returns to London.’⁵⁴

In August 1918, Cecil was also busy setting up a department within the

Foreign Office that would deal with the Middle East, Egypt and Persia. Almost

three years previously, Sykes had already urged upon him the establishment of

such a department, and at the end of July Lord Robert had requested Sir Mark to

draw up ‘a rough draft of the scheme of organisation

for Middle Eastern affairs’.⁵⁵ In a note he sent to Hardinge one month later,

Cecil explained how he envisaged the new department. He laid particular stress

on the fact that the problems Britain confronted in Egypt, Arabia, Palestine

and Mesopotamia were ‘mainly administrative and not diplomatic […] they should

be dealt with by a special Department of the Office, which should be largely

staffed by persons with administrative experience’.⁵⁶

Hardinge supported the idea that a Middle East Department should be

established as soon as possible, but disagreed with Cecil on who should be the

under- secretary in charge of it. Lord Robert had first considered Sir Arthur

Hirtzel, but had reached the conclusion, so he explained to Balfour, that

Hirtzel ‘for various reasons, including your dislike of I.O. officials […]

would not do’. He had subsequently opted for Crowe.⁵⁷ Hardinge agreed that

Hirtzel was ‘not at all suitable’, but according to him Crowe would not do

either, because the latter had neither Middle Eastern expertise nor experience.

He proposed Graham instead. The latter had spent many years in Egypt, and was

‘the soul of loyalty and would, I am convinced, make the new department a

success’.⁵⁸ Lord Robert, however, held on to Crowe. He informed Hardinge the

next day that he had telegraphed to Balfour, who was away on holiday, on the

subject ‘telling him what you have suggested and explaining quite definitely my

view that I would rather not attempt the scheme at all unless I am permitted to

have in charge of the department someone with whom I can work

satisfactorily’.⁵⁹ Balfour was rather puzzled by Cecil’s attitude. He had ‘no

reason to question your estimate of Crowe – you have seen more of his work than

I have. But surely you underestimate Graham? He has industry, good sense, and

[…] ability; and though I think Crowe is probably the cleverer man is it so

clear that he has the sounder judgment?’ Balfour also pointed out that ‘so far

as actual experience is concerned, Graham is the better man’.⁶⁰

In a long reply written the next day, Lord Robert set out his ‘case

against Graham’. When Cecil had discussed the matter with him, Graham had been

‘against the whole proposal’, and he was still ‘almost passionately anxious to

retain Egypt as part of the ordinary Foreign Office organisation’.

Graham really had the ‘diplomatic mind’ and would ‘never be a good

administrative official’. He added for good measure that Graham had ‘been quite

useless to me in Middle Eastern affairs during Hardinge’s absence. Indeed he

really knows less about them than I do.’ What it all amounted to was that

Graham did ‘not suit [him] as a subordinate’, while with Crowe it was the

opposite. The ‘Hardinge–Graham mind’ was no use to him, ‘whereas Crowe’s suits

me exactly’. Cecil observed in conclusion that ‘as you have asked me to do this

work I do very earnestly beg that I may be allowed to have the assistance which

I believe to be essential to me’.⁶¹ Balfour gave in. On 28 August, he informed

Drummond that he had telegraphed to Cecil

that Crowe should be appointed.⁶² Three days later, Cecil reported to

Balfour that ‘the Crowe incident is closed. I gather the appointment has given

very general satisfaction in the Office.’⁶³

None of the protagonists in the conflict had thought of making the acting

adviser on Arabian and Palestine affairs head of the new Middle East

Department. During the greater part of the month of August, Sykes had been away

from the Foreign Office. He had stayed for a few weeks at his home at Sledmere

to recuperate. When he returned and was confronted with the creation of this

new department for which he had drafted a first outline but of which Crowe was

in charge, he lodged a feeble protest with Lord Robert. He thought it ‘only

right that I should point out that under this arrangement I drop down in the

scale. I advised Lord Hardinge who passed the stuff on to the Secretary of

State. Under the present arrangement I advise Sir Eyre Crowe who advises Lord

Hardinge, and when the stuff comes back it will have to go back to Sir Eyre

Crowe,’⁶⁴ but left it at that.

Allenby’s Offensive and the

Capture of Damascus

On the morning of 19 September 1918, the EEF opened an attack on the

Turkish lines in what became known as the battle of Megiddo. As Archibald

Wavell, who served on the staff of Allenby’s XX Corps, noted in his book on the

Palestine campaigns, Allenby ‘had massed on a front of some fifteen miles […]

35,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry and 383 guns. On the same front, the unconscious

Turk had only 8,000 infantry with 130 guns […] The battle was practically over

before a shot was fired’.⁶⁵ The Turkish defeat was complete by 21 September.

Five days later, Allenby ordered the advance on Damascus.

The occupation of Damascus offered another opportunity to get the French

to accept that changes in circumstances prevented the execution of the Sykes–

Picot agreement, this time by creating facts on the ground. If an Arab

administration had been established in area ‘A’ before French officials and

soldiers arrived, then France would have no other option but to accept the fait

accompli, and to give up her imperialistic designs. On 23 September, Ormsby

Gore urged Sykes that Faysal, whose force operated on the right flank of

Allenby’s army, should be proclaimed ‘Emir in the event of our capturing

Damascus. We should recognise Arab government there

at once.’⁶⁶ A first step was to recognise the

belligerent status of Faysal’s troops. On 24 September, the Director of

Military Intelligence was informed that the Foreign Office had wired to Lord

Derby − Bertie’s successor at the Paris embassy − that ‘the time has come for

formally recognising the belligerent status of the

friendly Arabs operating in the Palestine– Syrian theatre against the Turks’.

In a subsequent letter four days later, the Foreign Office went one step

further by proclaiming that:

In pursuance of the general policy approved by His Majesty’s Government,

and in accordance more particularly with the engagements into which they have

entered with the King of Hedjaz, the authority of the friendly and allied Arabs

should be formally recognised in any part of the

Areas A and B, as defined in the Anglo–French agreement of 1916, where it may

be found established, or can be established, as a result of the military

operations now in progress.

This implied that these territories should be treated as ‘allied

territory enjoying the status of an independent state, or confederation of

states, of friendly Arabs which has in consequence of its military successes

and the organisation of a government (or governments)

established its independence of Turkey’. The Foreign Office also reminded the

Director of Military Intelligence that:

If and where the Arab authorities request the assistance or advice of

European functionaries, we are bound under the Anglo–French agreement to let

these be French in Area A. It is important from this point of view that the

military administration should be restricted to such functions as can properly

be described as military, so as to give rise to no inconvenient claim to the

employment of French civilians where unnecessary. It is equally important to

keep our procedure in that part of Area B, which lies East of the Dead Sea and

of the Jordan-Valley, on the same lines, so as not to give the French the

pretext for any larger demands in Area A.⁶⁷

Allenby could not have agreed more. On the day he had ordered the

advance on Damascus, he also issued a ‘Special instruction’ to the Australian

Mounted Division, which spearheaded his offensive, that ‘while operating

against the enemy about Damascus care will be taken to avoid entering the town

if possible. Unless forced to do so for tactical reasons, no troops are to

enter Damascus.’⁶⁸ Damascus should not surrender to British troops, but to

Faisal’s Northern Arab Army. Tactical reasons, however, forced the Australian

Mounted Division’s hands. The attempt ‘to pass around Damascus’ in pursuit of

the retreating Turkish army had to be abandoned because ‘the terrain was too

rugged’.⁶⁹ This had the result that in the early morning of 1 October 1918, the

10th regiment Australian Light Horse entered Damascus on its way to Homs.

According to Cyril Falls, the official historian of the campaign:

Once in the streets the horsemen were compelled to pull up to a walk,

for they found themselves surrounded by a population gone mad with joy […]

Major Olden dismounted for a few minutes at the Serai or Town Hall, where he

found sitting a committee, under Mohammed Said [Sa’id al-Jazairi],

a descendant of Abd el Kader, the famous Algerian

opponent of the French, who declared that he had been installed by Jemal Pasha

as Governor the previous afternoon, and formally surrendered the city to him.⁷⁰

Lawrence arrived in Damascus around 9:00 a.m. That same day he sent a

telegram to General Headquarters in which he reported his reception ‘amid

scenes of extraordinary enthusiasm on the part of the local people. The streets

were nearly impassable with the crowds, who yelled themselves hoarse, danced,

cut themselves with swords and daggers and fired volleys into the air.’ He and

his companions had been ‘cheered by name, covered with flowers, kissed

indefinitely, and splashed with attar of roses from the house-tops’. Lawrence

also mentioned that Shukri al Ayubi, a local supporter of Faisal, had been

installed as military governor, but failed to mention that he had dismissed the

Arab administration appointed by Djemal Pasha that had surrendered Damascus to

the British troops.⁷¹ Only one week later, the Foreign Office learned from

Clayton that he had: Ascertained [that]

a certain Ammed Sayed and Abd Elara Kader el Jezari [Abd al-Qadir, the

brother of Sa’id al-Jazairi] attempted to usurp civil

control in Damascus during Turkish withdrawal on September 30th but were

dismissed by Emir Feisal’s representative and Abd el

Kader imprisoned on October 2nd after his attempt to inflame local Moslem

opinion against the Christian and Shereffian

occupation which had led to rioting by Moors and Druses in Damascus.

Clayton apologized that he had not reported this incident sooner, but he

‘did not consider it advisable to telegraph vague rumors and unsubstantiated

reports’.⁷²

Allenby wired to the War Office on 6 October that he had visited

Damascus three days before, and that ‘Sharif Feisal made his entry amid the

acclamation of the inhabitants same day’. During an interview he had informed

the Emir that he ‘was prepared to recognise the Arab

administration of occupied territory East of the Jordan from Damascus to Maan

inclusive as a military administration under my supreme control’. He had

further told Faisal that he would ‘appoint two liaison officers, between me and

the Arab Administration, one of whom would be British and the other French and

that these two officers would communicate with me through my Chief Political

Officer’.⁷³ Allenby did not mention that Faisal had ‘objected very strongly’ to

this arrangement, ‘as he knew nothing of France in the matter’, and that he had

felt it necessary to remind Faisal that the latter was under his command and

had to obey orders. Faisal had finally ‘accepted this decision and left with

his entourage’.⁷⁴

On 7 October, Allenby did report that trouble had arisen with respect to

Beirut. The French political officer Captain Coulondre

had officially protested to Faisal about the latter hurriedly sending Arab

troops to occupy that city. Faisal had claimed that he had sent these troops

‘for purely military reasons to prevent disturbance’, and had ‘indignantly

denied charge of any ulterior motive and bad faith’. Allenby, however, had no

hesitation in pointing out that ulterior motives were involved. The Arab nationalists

were intent on exploiting the formula for the second type of areas

distinguished in the Declaration to the Seven, which referred to ‘areas

emancipated from Turkish control by the action of the Arabs themselves during

the present war’, where Britain recognized ‘the complete and sovereign

independence of the Arabs inhabiting these areas’. This clause applied to the

past. It covered the areas that had been liberated since the beginning of

Hussein’s revolt. Syria was covered by the fourth type of areas that had been

distinguished, those that ‘were still under Turkish control’, and in respect to

which the British government had only expressed their wish and desire that ‘the

oppressed peoples of these areas should obtain their freedom and independence’.

According to Allenby, the Arab nationalists interpreted the formula adopted for

the second type of area as a promise that Britain would recognise

the complete and sovereign independence of all areas liberated by the Arabs

themselves.⁷⁵ This was the reasoning behind Faisal’s rush to Beirut. After

Faisal’s troops had reached Beirut, Shukri al- Ayubi had been installed as

governor, and the Sherifian flag hoisted. This was

unacceptable to Allenby. Beirut was in the blue area and he therefore appointed

a French military governor, while Faisal was ordered to withdraw his forces.

Faisal initially refused to do so. On 11 October, Clayton wrote to Wingate that

he must ‘go to Damascus and give Faisal a talking to, as he is getting rather

out of hand’. Faisal should understand that he would ‘surely prejudice his case

before the Peace Conference if he tries to grab’. It would be far better if the

latter ‘should devote his energies to forming a sound and reliable

administration in Damascus and the “A” and “B” areas, so that he may have

something tangible to show at the Peace Conference’.⁷⁶

Clayton had his talk with Faisal on 14 October. The latter had tendered

his resignation the day before, in protest against the lowering of the Arab

flag at Beirut, but had been persuaded to postpone it.⁷⁷ Faisal explained to

Clayton that he regarded himself as ‘a guardian who has pledged his honour to secure the freedom and independence of the Arab

people of Syria’, and emphasized that ‘the people of Beirut and other coastal

towns took the first possible opportunity of

declaring for Arab government’. He nevertheless acquiesced in Shukri’s

removal, and when he was informed that ‘no flags will be flown in Beirut’, he

was also ‘satisfied regarding the lowering of the Arab flag’ there.⁷⁸ In a

further telegram, Clayton took the opportunity to drive home once more that

‘the crux of the situation’ still was the ‘necessity for definitive declaration

of policy by the French and British governments to the effect that there will

be no question of annexation whether open or veiled in any part of Syria. Arabs

will not wish to accept French assistance without this declaration.’⁷⁹ Allenby

fully agreed. He warned the War Office that ‘the general feeling of uneasiness

on the parts of the Arabs can only be dispelled by public declaration of policy

by the French and British governments’.⁸⁰ Both Clayton and Allenby were not

aware that, as Crowe minuted on Clayton’s telegram,

‘the public declaration of policy desired by General Clayton is being prepared

in consultation with the French’.⁸¹

The Foreign Office’s Window of Opportunity and the Joint Declaration

Four days after the launch of Allenby’s offensive, Balfour, who

substituted for Cecil as the latter was away on holiday, received Paul Cambon.

The French ambassador reminded the foreign secretary that Syria was ‘by the

Sykes–Picot Agreement, within the French sphere of influence, and it was

extremely important from the French point of view that this fact should not be

lost sight of in any arrangements that General Allenby, as Commander-in-Chief,

might make for the administration of the country’. Subsequently, they had ‘a

conversation of considerable length, in which Sir Mark Sykes, the joint author

of the Sykes–Picot Agreement took a part’. In the end, completely bypassing the

Eastern Committee, Balfour:

Drafted for M. Cambon’s guidance the following statement of policy,

which seemed to me to be required by the letter and spirit of the Agreement:–

Private.

The British government adhere to their declared policy with regard to

Syria: namely that, if it should fall into the sphere of interest of any

European Power, that Power should be France. They also think that this policy

should be made perfectly clear both in France and elsewhere.

The exact course which should be followed by the two governments in case

General Allenby takes his forces into Syria should be immediately discussed in

Paris or London. But it is understood that in any event, wherever officers are

required to carry out civilian duties, these officers should (unless the French

government express an opinion to the contrary) be French and not English;

without prejudice of course to the supreme authority of the Commander-in-Chief

while the country is in military occupation.

Balfour in one stroke regained for the Foreign Office the initiative in

formulating British policy towards the Middle East. He also confirmed the

policy that Cecil and Sykes had been advocating for months that Britain should

without reserve recognize the French claims in Syria and the Lebanon that

flowed from the Sykes–Picot agreement, but which had time and again been

thwarted by the Eastern Committee. For the moment, however, the Eastern

Committee remained unaware of Balfour’s initiative. The day after the

interview, the Foreign Office did inform the Director of Military Intelligence

that Bal- four had telegraphed to Derby that ‘if General Allenby advances to

Damascus it would be most desirable that in conformity with the Anglo–French

Agreement of 1916 he should if possible work through an Arab Administration by

means of French liaison’. It also suggested that ‘this telegram should be

repeated to Sir E. Allenby for his guidance’.⁸² It was only at the Eastern

Committee’s meeting of 26 September that Balfour related that he had drawn up

‘a brief statement of policy’, which ‘had been cabled the same evening to our

Ambassador in Paris’. He assured the committee that copies of his note would be

circulated, but suggested that ‘the further discussion of the subject should be

postponed until members were in possession of these papers’. Curzon was quite

taken aback. He declared that ‘he regarded the question as one of the utmost

importance. The Foreign Office appeared now to be relying upon the Sykes–Picot

Agreement from which the Committee had hitherto been doing their best to

escape.’⁸³

On 27 September, on the eve of Georges-Picot’s visit to London (see

‘Mitigating or Abolishing the Sykes–Picot Agreement’, above), Cambon called

upon Cecil. The ambassador explained that ‘in the existing state of things it

would scarcely do to leave the negotiations in the hands of Sir Mark Sykes and

M. Picot exclusively’, and proposed that ‘M. Picot might be accompanied by

somebody from the French Embassy, and Sir Mark by someone from this office’.

Cecil agreed that ‘it was desirable that the negotiations should be rather more

formal than they had been’, and suggested that Cambon and he should both

preside.⁸⁴

The Anglo–French conference took place on 30 September. On the

proposition of Lord Robert, and ‘subject to the confirmation of the British and

French governments’, it was agreed that:

In the areas of special French interest, as described in the

Anglo–French Agreement of 1916, which are or may be occupied by the Allied

forces of the Egyptian expeditionary force, the Commander- in-Chief will recognise the representative of the French government as

his Chief Political Adviser. The functions of the Chief Political Adviser will

be as follows:

1. Subject to the supreme authority of the Commander-in-Chief, the Chief

Political Adviser will act as sole intermediary on political and administrative

questions between the Commander- in-Chief and any Arab government or

governments, permanent or provisional, which may be set up in Area ‘A’, and recognised under the terms of clause 1 of the Agreement of

1916.

2. At the request of the

Commander-in-chief, and subject to his supreme authority, the Chief Political

Adviser will be charged by the Commander- in-Chief with the establishment of

such provisional administration in the towns of the Syrian littoral situated in

the blue area, and in the blue area in general.

3. Subject to the approval of the

Commander- in-Chief, the Chief Political Adviser will provide […] Such European

advisory staff and assistants as the Arab government or governments set up in

Area ‘A’ may require under clause 1 of the Anglo–French Agreement of 1916 […]

Such personnel as may be necessary for civil duties in the littoral towns or

other parts of the blue area.

The conference also decided that the ‘above arrangement shall remain in

force until such time as the military situation justifies reconsideration of

the question of civil administration and political relations’, and to recommend

to their respective governments that they:

Take an early opportunity to issue a declaration, or declarations,

defining their attitude towards the Arab territories liberated from Turkish

rule. Such a declaration should make it clear that neither government has any

intention of annexing any part of the Arab territories, but that, in accordance

with the provisions of the Anglo–French Agreement of 1916, both are determined

to recognise and uphold an independent Arab State, or

confederation of States, and with this view to lend their assistance in order to

secure the effective administration of those territories under the authority of

the native rulers and peoples.⁸⁵

The policy urged by Sykes and Cecil of faithfully adhering to the terms

of the Sykes–Picot agreement, but at the same time preventing the French from

realizing their imperialistic plans by binding them through a joint declaration