By Eric Vandebroeck

Underneath the

beginning of the Gala performance in Beijing with performers from ethnic

minority groups in traditional costume during China’s 70th National Day.

Understanding modern China.

Central to the

self-understanding of the Chinese leadership today is the

concept of Han Chinese an idea

that derived from the Song period when the first form of diplomatic cosmopolitanism

was conceived. It was during the described Song period that Chinese

colonists spread relentlessly southward, recurrently provoking armed opposition from tribal

groups in their path.

One challenge faced

historically by the agricultural and stationary Han civilization was that it

was surrounded to the north and west by nomadic tribes, with fluctuating

borders and populations in the mountains and dense forests to the south. To

secure the Han core, China historically fought, and occasionally was overcome

by, its neighbors (particularly the powerful nomadic tribes to the north). To

manage its regional position, China established a Middle Kingdom policy whereby it kept neighbors at bay with a parallel

policy of integration and accommodation for the nearby buffer regions while

employing a nominal tributary system to deal with its slightly more distant

neighbors.

It was through

the Han expansion that

China made its first contacts with peoples outside of the traditional Chinese

sphere, as its emissaries reached as far as Parthia (in modem Iran), China

developed its earliest firsthand knowledge and understanding of

other-particularly Western-cultural worlds. Second, the triumphant military

expeditions implanted the Middle Kingdom idea firmly and visibly in the

Chinese the worldview of international relations, in which China was the center and superpower of the

world and other peoples and countries were referred to only in a tributary and

subordinate terms.

Throughout its history, China’s boundaries underwent

constant fluctuations.

Thus the ruling political party of the People’s Republic

of China’s current allegiance to the unchanging never-never land of a timeless

past is clear in its delineation of China’s borders, based on the furthest

reaches of a Manchu-led empire, the Qing, but claimed to be eternal and

perpetually “Chinese.”

But it is the Maoist

period that largely shaped China’s contemporary boundaries and geopolitical

landscape. The internal weakening of the Qing Dynasty in the 18th and

19th centuries provided ample opportunities for

imperial exploitation of China by Europe and later Japan.

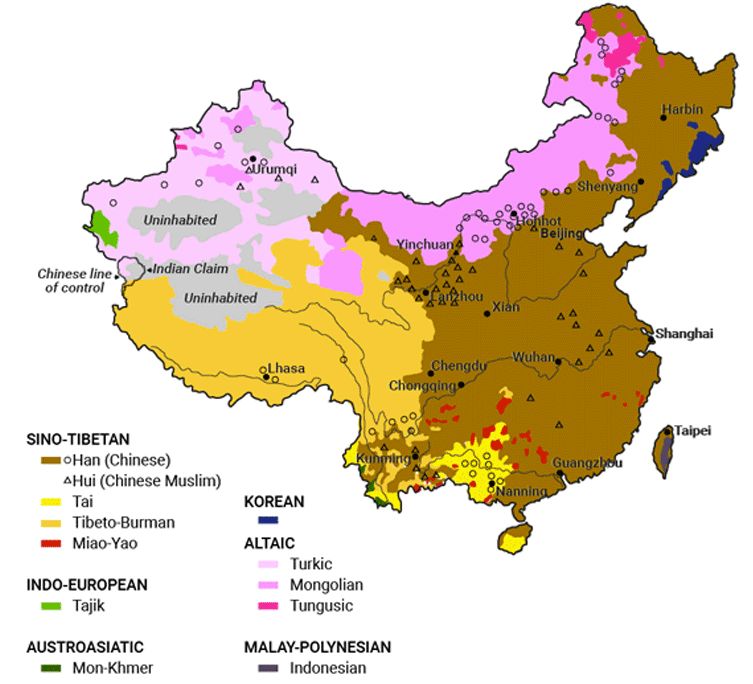

One of Beijing’s

greatest fears about the buffer regions stems from the manner

in which China assimilated them into the country. Unlike the Soviets,

who moved non-Russian ethnic groups around to avoid contiguous ethnicities

across borders, China moved Han Chinese into the buffer regions, slowly

diluting the local populations. China still fears Pan-Turkic movements spreading through Central Asia

into Xinjiang; large, organized ethnic Tibetan populations in India; Inner

Mongolian herdsmen potentially seeking reunification with Mongolia; ethnic

Koreans on the Chinese side of the Yalu River forging ties with a future

unified Korea; and numerous ethnic minority and even

militant groups moving along the borders of Southeast Asia.

China Dialects

The weakness of China

was (and may remain) the internal diversity of geography, history, economic

activity, and regionalism. As noted above, the Han core appears largely

unified, but underneath is extremely complex and fragmented. China has

north-south divisions, coastal-interior divisions, core-periphery divisions,

rural-urban divisions, and increasingly, have-and have-not divisions. Balancing

these differences requires a deft hand at the center. And, with China’s current

economic slowdown, this balancing act is growing more difficult. China’s size

has led to a historic pattern of expansion and contraction based on internal

crises more often than external threats, though as anywhere, severe internal

crises can pave the way for external actors to move in.

See also my case

study about the new nationalism project started following the 1989 Tiananmen

crackdown.

What also should be

noted is that China’s economic success has broken its self-sufficiency. Now, it

imports at least as much of its key industrial commodities as it produces.

Foreign trade is a vital piece of China’s economic activity, even as the

country attempts to drive its economy toward a domestic consumption model.

Outbound investments provide access not only to markets and resources but also

to technology and skills. This has compelled China to seek ways to secure

its vulnerable supply lines, expand its maritime presence and extend its

international financial and political presence.

Gala performance with performers from ethnic

minority groups in China

later in the evening:

For updates

click homepage here