There is a rumor that President Mohamed Morsi might be willing to annul

the decree he issued last month, however he would not back dawn on the vote for

the new constitution. The country's main opposition parties however maintain

that the draft constitution is biased and have rejected Morsi's call for

dialogue.

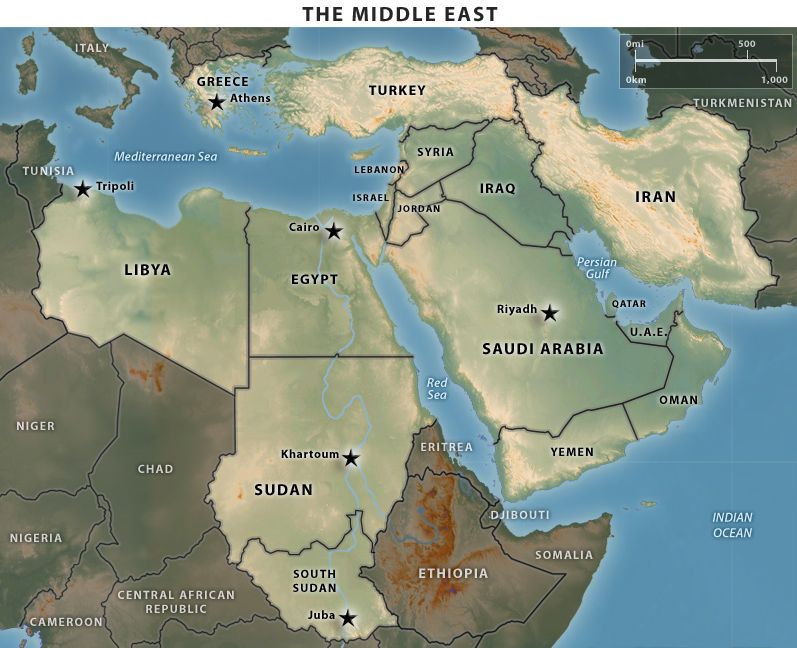

From Egypt to Syria to Jordan, relics of the post-Ottoman Middle East

are struggling for relevancy amid a rising Islamist tide. Whether Nasserite or

monarchist, the models that have defined this region over the past century are

either being altered significantly or headed for obsolescence.

In Egypt today opposition protesters have demonstrated outside the

presidential palace in Cairo, after breaking through a barricade erected by

security forces. Whereby it should be understood that Morsi did not call on the

Republican Guard the way U.S. President Barack Obama would call on the National

Guard. The military acted only when it wanted to.

The Egyptian military thus remains the central power in Egypt. Despite

efforts by the Muslim Brotherhood and President

Mohammed Morsi to gain control over the senior military leadership, the

Brotherhood does not control the military. The Brotherhood is not totally

powerless, but it is the weaker of the two. This dynamic is fundamental to

understanding where Egypt is and what decisions its leadership can make

domestically and in foreign relations.

Notably, the military does not want to completely destroy the

presidency. It needs a civilian partner, and the Brotherhood currently is its

only viable option. But it does not want the Brotherhood to become too powerful

either.

Important however is that although the Brotherhood previously rejected

such concessions, the new draft charter represents the group's realization that

it needs the military to advance its agenda in the current environment. An

article published by the Washington Institute on 3 December in fact spells out 'the

Brotherhoods deal with the Military'.

Meaning: First, the new constitution grants the military relative

autonomy over its own affairs. Article 195 holds that the defense minister must

be a member of the armed forces "appointed from among its officers,"

thereby sparing the military from civilian oversight. Article 197 similarly

establishes a National Defense Council to oversee the military's budgets; at

least eight of the council's fifteen seats must be held by high-ranking

military officials, avoiding the parliamentary oversight that the generals

feared. Meanwhile, Article 198 maintains the military judiciary as "an

independent judiciary" and allows civilians to be tried before military

courts for "crimes that harm the armed forces."

Second, the constitution grants the military substantial influence --

and perhaps even veto power -- over the conduct of war. Article 146 states that

the president cannot "declare war, or send the armed forces outside state

territory, except after consultation with the National Defense Council and the

approval of the House of Representatives with a majority of its members."

The text also seemingly equalizes the defense minister and the president during

wartime: Article 146 calls the president the "supreme commander of the

armed forces," while Article 195 declares the defense minister the

"commander-in-chief of the armed forces."

This is the reality in Egypt. The situation has been clouded with

uncertainty since August, when Morsi forced the retirement of several senior

military leaders, including Supreme Council of the Armed Forces chief Mohamed

Hussein Tantawi and armed forces chief Sami Annan. The question was whether

Morsi's moves made the military subordinate to civilian authority.

Whereas the unrest this past week stems from Morsi’s November 22 decree,

in which he granted himself near-absolute powers, including immunity from

judicial oversight of his decisions. Morsi has been

pushing for a constitutional referendum in December despite the

opposition’s outspoken criticism of the document, which under the Muslim

Brotherhood and Salafists's

pressure is designed to keep “the principles of sharia” law as the main source

of legislation.

Thursday then, the military put tanks outside the palace and 3pm curfew

was proclaimed. Even so, hundreds of people streamed into the streets at

nightfall, some of them demanding Morsi’s November decrees be retracted, others

thrusting their support behind the Egyptian leaders – and many others still

just protesting the recent deaths.

The military allowed the situation to evolve until Morsi was desperate

and had to negotiate with the military leadership. A bargain may be

forthcoming, but ultimately the deal they make matters less than the balance of

power. The fact that Morsi had no choice but to ask for the military's help --

and the fact that the military did not act before negotiations -- confirms that

Morsi does not control the military. The military has shown the public that it,

not the civilian government, is the arbiter of power in Egypt. Notably, the

military does not want to completely destroy the presidency. It needs a

civilian partner, and the Brotherhood currently is its only viable option. But

it does not want the Brotherhood to become too powerful either.

Soon after that President Morsi addressed the nation accusing the

foreign-funded opposition of trying to incite violence against his legitimacy.

"I separate the legitimate opposition from the vandals who committed

violence,” said Morsi. “The opposition thinks Article 6 is a problem. I won’t

insist on keeping it, and anyway, the decree ends after the referendum.”

During the constitutional referendum Morsi is also unlikely to

compromise because of his intimate familiarity with the Brotherhood's

unparalleled mobilizing capabilities. Specifically, the Brotherhood is

structured such that its Guidance Office can direct thousands of

five-to-eight-person cells known as families,

which are situated in practically every Egyptian neighborhood, to any location

that it chooses. During last year's revolution, this structure was vital to

ensuring a mass Brotherhood turnout at the uprising's most pivotal moments, and

Morsi himself was responsible for commanding Brotherhood cadres' activities

within Tahrir Square. The Brotherhood remains extremely confident that it can

overwhelm its current opponents, and Morsi is unlikely to respond to protests

that his own supporters can exceed.

This is, in fact, precisely what the Muslim Brotherhood will do, when it

is likely to unite with Salafist organizations

and hold a mass demonstration in front of Cairo University. For Morsi, the

Islamists' inevitably impressive turnout will likely affirm his claim that

"around 90 percent" of Egyptians support him, and validate his

attempt to rush the Islamist-drafted constitution to a national referendum. But

for Morsi's secularist opponents, the Islamists' mass mobilization to support a

naked power grab represents a call to arms, and they are bracing for the worst.

Add to this Syria and Jordan

In Syria, rebels were closing in on Damascus while U.S. Secretary of

State Hillary Clinton met with her Russian counterpart Thursday apparently to

discuss how to avoid a chemical weapons disaster in Syria following the

departure of President Bashar al Assad. Russia may also be using its

interactions with the United States to present counter

evidence to recently leaked U.S. intelligence claims about Syria's chemical

weapons activity. Moscow's intent would be to undermine what appears to be a

psychological campaign by the United States aimed at further fracturing the al

Assad government through fear of a foreign military intervention.

From the point of view of Moscow, a beneficiary of the embattled Alawite regime, maintaining as much of the state

machinery as possible (including a prominent role for the minority Alawites) is

the best path forward to stabilize Syria and at the same time ensure a strong

Russian stake in the Levant. The only adjustment that needs to be made to the

system, as far as Russia is concerned, is the removal of the al Assad clan

through some sort of amnesty deal. The United States and Turkey are also trying

to avoid a level of state collapse that would draw them into a military

campaign in Syria, but are looking for a larger share of power for Syria’s

Sunni majority that would limit Iranian influence and (to Turkey’s benefit)

embolden the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria. In other words, possible adjustments

to the Syrian military republic model remain under debate and may even be well

beyond the control of the negotiators in question.

In Jordan, the Hashemite kingdom is struggling to avoid concessions that

will empower an already-emboldened Muslim Brotherhood-led opposition that is

now openly calling for the downfall of the monarchy. Jordanian

King Abdullah II spent Thursday on a visit to the West Bank to demonstrate

his support for Fatah leader and Palestinian National Authority President

Mahmoud Abbas after the latter's U.N. bid for Palestinian recognition. This

visit embodies the obsolescence of the post-Ottoman era. The U.N. bid

notwithstanding, Fatah and the secular left of the Nasserite era have long lost

their credibility in the Palestinian arena. Hamas and its Islamist allies are

meanwhile making strides with the regional rise of the Muslim Brotherhood at

the expense of fraying ancient regimes. In the latest Gaza crisis, Abbas could

not even attempt to claim to speak on behalf of Gaza in trying to defuse the

conflict. Yet Abbas and Abdullah continue to visit each other on a regular

basis, unaware or perhaps deliberately blind to the idea that they are now

relics of another time.

For updates click homepage

here