By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

For reference see a list of the personalities

connected with British foreign policy towards the Arab Middle East, 1914–19.

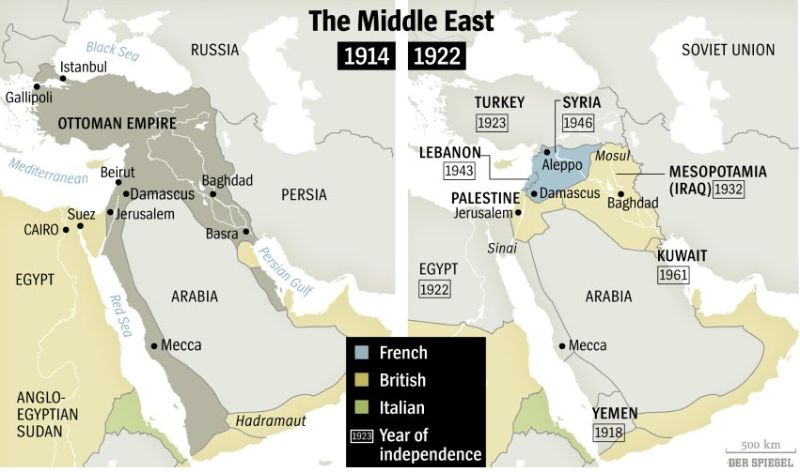

The profound effects of the British Empire’s actions in the Arab World

during the First World War can be seen echoing through the history of the 20th

century. The uprising sparked by the Foreign Office authorizing Sir Henry

McMahon to enter into negotiations with Sherif Hussein, and the debates

surrounding the Sykes–Picot agreement have shaped

the Middle East into forms which would have been unrecognizable to the

diplomats of the 19th century.

The crux the explanation of these events, which now loom so large, is

that Edward Grey and his Foreign Office officials were not very much alive to

the significance of what they were doing because for them Middle Eastern

affairs were simply not that important. This meant that as long as Grey and his

civil servants perceived the advice of various experts not to be inconsistent

with the essence of the Foreign Office’s policy – to uphold the Entente with

France – they were prepared to follow it.

This is why they acted without much ado upon recommendations by Lord

Hardinge, Lord Kitchener, Sir Reginald Wingate, McMahon and Sir Mark Sykes,

even when these contradicted one another. This tendency was especially

prominent during the first months of the war when Cairo was alternately

instructed to encourage the Arab movement in every way possible and to refrain

from giving any encouragement.

The sudden change in the summer of 1915, from a policy of restraint

concerning the Middle East to an active, pro-Arab policy, may also be explained

in this manner. Perhaps Wingate and McMahon were able to outstrip the India

Office and the Government of India as the Foreign Office’s premier advisors on

the Arab question because they were, after all, in the service of the Foreign

Office, perhaps because Austen Chamberlain had succeeded Lord Crewe as

secretary of state for India, but the main point is that Sir Edward and his

officials need not have had ‘good’ reasons for thinking that Wingate and

McMahon were in a better position to judge how to react to Hussein’s opening

bid. Wingate’s letters and memoranda played a role in the Foreign Office’s

conversion to a more active, pro-Arab policy, but it is highly improbable that

Grey and his officials would have been receptive to Sir Reginald’s arguments if

they had invested heavily in the policy of restraint advocated by the Indian

authorities.

The negotiations that led to the signing of the Sykes– Picot agreement

presented to the Foreign Office more a technical problem than a politically

sensitive one. Once it was realized that the conflicting claims of Arabs and

French regarding Syria were amendable to a settlement – as Wingate, Sir John

Maxwell, McMahon, Aubrey Herbert and Sykes, one after the other, had emphasized

– the Arab question became something of a routine affair, something that was

covered by the rule that nothing should be done that might arouse France’s

Syrian susceptibilities. The negotiations with the Emir of Mecca could only be brought to a close after those with the

French had successfully been concluded. Even though the authorities in

Cairo, and Sykes, urged the vital importance of a quick reply to Hussein’s

overtures, the negotiations with the French, as these entailed consultations

with the relevant departments as well as with Russia, simply had to run their

course. This also implied that once these negotiations were under way it was

very difficult to stop them. Neither the information that the Arabs were in no

position to rise against the Turks (which seemed to have knocked the bottom out

from under the raison d’être of the negotiations) nor that Hussein was not the

spokesman of the Arabs (which appeared to imply that, perhaps as far as the

Arab side was concerned, there was nobody to negotiate with) halted their

progress. Regarding the relative importance of the Arab question, it is

naturally also very telling that, after the Anglo–French agreement had been

signed in the middle of May 1916, nobody in the Foreign Office observed that

the way was now clear to finalize the negotiations with the Emir of Mecca, or

noticed, at the beginning of June, that he had started his revolt before the

negotiations with him had been completed.

For British policy makers, the sending of British troops to Rabegh was unquestionably an important question as far as

the Middle East was concerned during the years of the Asquith governments. They

were very much alive to the significance of this question, now completely

forgotten. Some ministers, notably Lord George Curzon, Chamberlain, Grey,

Arthur Balfour and David Lloyd George, dissatisfied with the manner in which

the war was being conducted, believed that Rabegh

provided the opportunity to challenge the dominant view that the war could only

be won in France and that sideshows must be avoided at all costs. Although the

significance of the Rabegh question was largely

symbolic − a small ally, a small force − the stakes regarding credibility were

very high as a result of Sir William Robertson’s initial flat refusal even to

consider the dispatch of troops. This implied that the protagonists in this

controversy were very reluctant to put their credibility at risk. That is why

the War Committee’s policy on Rabegh amounted to the

decision to postpone the decision, even when it had been decided to take a

decision, and of course, this also applies to Wingate, the strongest advocate

of sending troops.

Another major event with far-reaching consequences for the present-day

Middle East is, of course, the private deal between Lloyd George and French

Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau on 1 December 1918, which brought Palestine

and Mosul into the British sphere. In the course of 1919, Lloyd George made

several attempts to get Clemenceau to accept yet another revision in Britain’s

favor of the boundaries laid down in the Sykes–Picot agreement. Clemenceau

greatly resented these given his concessions in December and started openly to

accuse Lloyd George of bad faith. This had the result that the settlement of

the Arabic-speaking parts of the Ottoman Empire turned into a highly personal

affair between the two prime ministers, in the course of which the credibility

stakes became higher and higher. By the autumn of 1919, only the two prime

ministers were still prepared to let the Middle East further burden

Anglo–French relations. In the end, Lloyd George gave

in as far as the south-eastern border of Syria was concerned, and had more or

less his way regarding the northern border of Palestine, but this only after

Clemenceau had left office.

As what the British decision-making on the Arab question 1914–19 is

concerned, noticeable is the rapid decline of the Foreign Office’s influence,

which set in after Balfour had succeeded Grey. During the first years of World

War I, British Middle East policy was very much the Foreign Office’s preserve,

and Grey, with the support of Prime Minister Henry Asquith, was eager to guard

the Foreign Office’s preeminence. Moreover, after 11 years as foreign

secretary, the Foreign Office had to a very large extent become ‘his’

department, so that Grey and his officials most of the time spoke with one

voice. This was altered drastically after the advent of the Lloyd George

government in December 1916. Compared to Grey, Balfour could only be an

outsider and continued to be so during the whole period of his tenure of the

Foreign Office. His reputation was not bound up with the department, and he ran

the office in much the same lackadaisical manner as he had run the Admiralty.

This left Lloyd George ample space to intervene in British Middle East policy

and to bypass the Foreign Office whenever he felt like it. A first occasion was

the conference of St Jean- de-Maurienne in April 1917

to settle Italian claims in the Eastern Mediterranean, where no representative

of the Foreign Office was present. The frequency of Lloyd George’s

interventions increased over time and in 1919, as far as the settlement of the

Syrian question was concerned, the Prime Minister was completely in command,

and the Foreign Office could only follow.

When he was chairman of the Eastern Committee, Curzon succeeded in

curbing the Foreign Office’s grip on Middle East policy, which was greatly

resented by Lord Robert Cecil, but when Curzon became acting foreign secretary

in January 1919, it soon became apparent that he totally lacked the power to

reverse the tide and reestablish the Foreign Office’s authority in this policy

area. I cannot imagine a better illustration of just how low the Foreign

Office’s reputation had sunk by the autumn of 1919, than Curzon having to

request Lloyd George that he be present at the negotiations with Faisal.

The eclipse of the Foreign Office also implied that the basis of its

policy towards the Middle East – that nothing must be done that might excite

French susceptibilities with respect to Syria – was gradually eroded from 1917

onwards, with the result that in 1919 Lloyd George, confident that he could

dictate terms to the French, had no qualms in treating these with contempt.

Where traditional Foreign Office policy implied that possible trouble in the

Middle East was to be preferred to trouble with the French, Lloyd George’s

priorities were exactly the opposite. In this connection, one should not fail

to point out that the policy advocated by Cecil in 1918, although at first

glance it might have looked like a return to the Foreign Office’s traditional

policy, actually was nothing of the kind. It was almost as hostile to French

interests as Lloyd George’s. Although Cecil accepted that Britain’s signature

of the Sykes–Picot agreement held good, at the same time he tried to undermine

the French position, by creating facts on the ground, trying to bind the French

to the principle of self-determination, and to induce the Americans to step in

and force the French to recognize that the agreement was inconsistent with the

spirit of the times. Where Lloyd George was blunt, Lord Robert was too clever

by half, and both failed in their attempts to get the French to give up their

acquired rights in Syria under the Sykes–Picot agreement.

Whenever ‘the men on the spot’ did not see eye to eye with the decision

makers in London, the former did not succeed in convincing the latter that the

policy they advocated should be abandoned, and a different one adopted.

Although officials, soldiers and ministers in London readily accepted that

their knowledge of Middle Eastern affairs was inferior to that of those who

were actually there (except Curzon and Sykes of course), at the same time they

did not doubt that their knowledge was superior, because they saw the bigger

picture, however vague that picture might be. This equally applied to the

Foreign Office’s traditional policy that nothing should be done that might

arouse French susceptibilities with respect to Syria, and to Balfour’s policy

to create in Palestine the conditions that would give

the Zionists the opportunity to establish a Jewish state (provided that the

rights of the existing population were respected). Concrete, practical

difficulties did not stand a chance against lofty principles and general

notions. At best, such difficulties were acknowledged in London while the men

on the spot were encouraged to bear with them. At worst, these were merely seen

as attempts by the latter to obstruct agreed policy and yet to have it their

way. The insensitivity of the London decision makers to the worries and

warnings of the British authorities in the Middle East triggered

the latter to depict the consequences if their policy proposals were not

adopted in the shrillest terms.

Disaster would surely follow if the demands of the Arab nationalists

were not met right away, if a brigade was not sent to Rabegh,

if the British government insisted on implementing the Balfour Declaration.

That same insensitivity, however, also had the result that when these dire

consequences failed to materialize, hardly anybody in London noticed this and

called to account those who had uttered these apparently empty threats. Sykes’s

temporary prominence in British Middle East policy was not the result of his

testimony before the War Committee after his tour of the Near and Middle East,

but of his success in coming to a speedy agreement with François Georges-Picot.

From May 1915 onwards, Curzon was the (War) Cabinet’s expert on Middle Eastern

affairs in residence, so to speak, and although he sometimes managed to thwart

the policy initiatives of others, especially Sykes’s, he never managed to put

his stamp on the main lines of British Middle East policy. Lloyd George, on the

contrary, even though he knew next to nothing about the Middle East, certainly

did.

The consequences of British

policy in the Middle East.

During the Paris peace conference, Augustus John painted a portrait of

T.E. Lawrence, dressed in Arab robes, including a dagger. It resonated with the

British public. According to Christine Riding, it distilled a Western

orientalist desire for power over the Orient, while suggesting that that power

in the figure of Lawrence would be exerted with ‘knowledge, understanding and

empathy’.1.

By the time Faisal himself arrived in Paris on February 6, 1919, to

present the case for Arab ‘self-government’ in Syria, Lawrence, and the British

had assembled an entire public relations team for him, pumping gullible

journalists (especially American ones) with tales of derring-do by the

Hashemite prince. Embracing his part, Faisal showed up to address the Supreme

Council wearing ‘white robes embroidered with gold,’ with ‘a scimitar at his

side,’ thus inaugurating the curious twentieth-century tradition of Arab

leaders addressing diplomatic assemblies while fully armed. In an inspired

touch, Lawrence ‘interpreted’ Faisal’s remarks to the Supreme Allied Council

himself (in fact Lawrence’s Arabic was rather poor, so that what he was really

doing was making Faisal’s arguments for him). Speaking for Faisal, Lawrence

said that the Arabs wanted, above all, self-determination. The Lawrence-Faisal

promotion, judging by the effusions of Colonel House (in whom Faisal ‘inspired

a kindly feeling for the Arabs’) and U.S. secretary of state Robert Lansing

(Faisal ‘seemed to breathe the perfume of frankincense’), thoroughly bamboozled

the Americans. The French, outmaneuvered, denounced the infuriating Faisal as ‘British imperialism with Arab headgear.’2

Below the Arabian Commission to the Peace Conference at Versailles and

its advisors.

Fear of French dominance and the need to establish an alliance that would

support his political ambitions led Faisal to initiate the United States’

Middle East initiative. The inquiry was, in part, a result of the Hashemite

prince’s choice not to reject the fresh mandates system outright while in

Paris—a decision that immediately generated much controversy within nascent

nationalist circles across bilad al-sham, or Greater

Syria.3

Lloyd George and the British believed that, in Faisal and his Arab

irregulars, they had an ace in the hole, a façade to rule behind.

Anticipating this very track, the French press sought to undermine

Faisal’s Arabs by playing up Lawrence’s role in leading them. Astonishingly, in

light of his later rise to world fame, Lawrence was entirely unknown to the

Western public before the end of the war, largely by design. Both Allenby and

his chief political officer, Gilbert Clayton, had concealed Lawrence’s role in

public communiqués so as not to compromise Faisal’s political prospects. As

late as December 30, 1918, Lawrence was unmentioned in the account of the fall

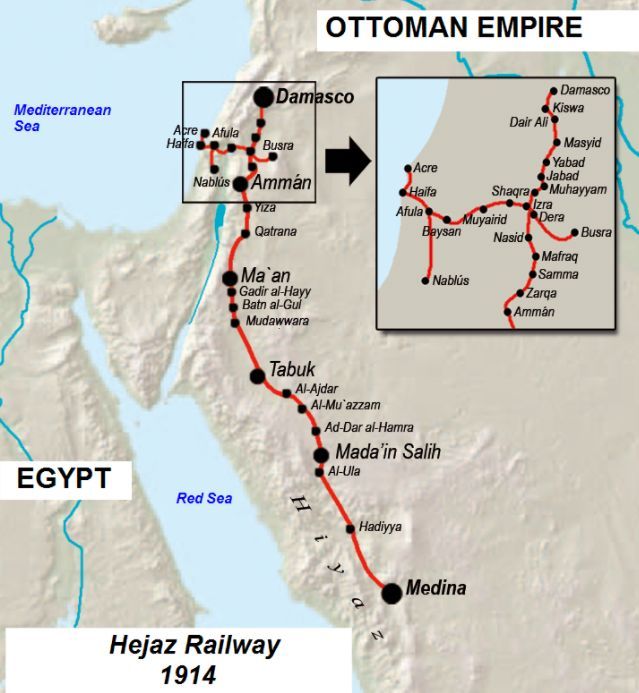

of Damascus published in the London Gazette. 4 It was actually a French

newspaper that first broke Lawrence’s 'cover,' expressly to belittle Faisal’s

Arabs. Colonel Lawrence, the Echo de Paris reported in late September 1918,

riding at the head of a cavalry force of 'Bedouins and Druze,' had 'sever [ed]

enemy communications between Damascus and Haifa by cutting the Hejaz railway

near Deraa,' thereby playing 'a part of the greatest importance in the

Palestine victory.'5

By introducing T. E. Lawrence to the world, the French scored an own

goal of the most self-destructive kind. Seeking to undermine Faisal, the Echo

de Paris had instead glorified Faisal’s greatest champion, a man born for the

role of mythmaker. Rather than deny his role in the Arab revolt, Lawrence

shrewdly manipulated his newfound fame, presenting himself not as an effective

liaison officer who had helped Arab guerrillas blow up some railway junctions

but as a witness to an Arab national awakening.6

There were differences among members of the British cabinet. Speaking at

a meeting of the Cabinet’s Eastern Committee in December 1918, Edwin Montagu,

Secretary of State for India, complained of drifting into a position ‘that

right from the east to the west there is only one possible solution to all our

difficulties, namely that Great Britain should accept responsibility for all

these countries’. 3 Whereby Churchill believed East and West Africa offered far

better opportunities for imperial development then the Middle East.7

Or as an adviser to the British delegation to the Versailles peace

conference also overheard Prime Minister Lloyd George musing aloud:

‘Mesopotamia … yes … oil … irrigation … we must have Mesopotamia; Palestine …

yes … the Holy Land … Zionism … we must have Palestine; Syria … h’m … what is

there in Syria? Let the French have that.’ 8 Other ministers sought to exploit

the opportunity created by Turkey’s defeat and Russia’s implosion to ensure

against a recrudescence of the latter’s power, and to strengthen the forward

defenses of India.

However, outlining his Fourteen Points in January 1918, Wilson declared:

There was to be free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment

of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in

determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations

concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government

whose title is to be determined. As to the Ottoman Empire, the non-Turkish

peoples ‘should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely

unmolested opportunity of autonomous development’.9

Although Wilson proved unable to impose his ideas on his European

allies, he had struck a powerful international chord. Even Mark Sykes acknowledged in March 1918 that the world had

moved on since his agreement with Picot, which could now ‘only be considered a

reactionary measure.'10

In November 1919 the British and French felt it necessary to declare

publicly that the end for which the two countries had prosecuted the war had

been ‘the complete and definitive liberation of the peoples long oppressed by

the Turks and the establishment of national governments and administrations

drawing their authority from the initiative and free choice of the indigenous

populations’.11 This was not, as events proved, to be taken at face value, not

least because part of the British motive in issuing the declaration had been to

try to undermine French claims to Syria. In Curzon’s words;

If we cannot get out of our difficulties in any other way we ought to

play self-determination for all it is worth wherever we are involved in

difficulties with the French, the Arabs or anybody else, and leave the case to

be settled by that final argument, knowing in the bottom of our hearts that we

are more likely to benefit from it than is anybody else.12

Wilson’s main influence, next was reflected in the new concept of League

of Nations mandates. To many they were simply a means of draping the crudity of

conquest in a veil of morality. That was the view certainly in Baghdad, where

in June 1922 Al-Istiqlal declared that ‘we do not reject the mandate because of

its name but because its meaning is destructive of independence’.13

Nevertheless, mandatory powers were accountable for their administrations of

the new territories to the League of Nations. Category A mandates, which

included those for the Middle East, were for countries nearly ready to run

their own affairs. The prospect of independence, in other words, was explicitly

recognised, with the power of the mandatory being

only temporary.14

Much would depend on the development of Arab nationalism. This could

only be exacerbated by the imposition of British hegemony in the place of an

Ottoman Empire, which had excited relatively little opposition and had at least

the advantage of being Muslim.15 The time had gone, as Major Hubert Young at

the Foreign Office noted in 1920;

when an Oriental people will be content to be nursed into

self-government by a European Power. The spread of Western education, increased

facilities of communication, and above all the War, with the resultant

emergence of the Wilsonian principle of self-determination, have combined to

breed in the minds of Eastern agitators, a distrust for, and impatience of,

Western control. We cannot ignore this universal phenomenon without

endangering, and possibly losing beyond possible recall, our position in the East.

The problem was not, in Young’s condescending view, insoluble, so long

as Britain was careful too, distinguish between the wild cries of the

extremist, anxious to secure for himself and deny to the foreigner what he

regards as the spoils of government, and the childish vanity of the masses on

which he brings his armory to bear. If we could but descend to tickling that

vanity ourselves, we should deprive the agitator of his most powerful weapon.16

Young’s solution, which was to work for the next two decades, was the

recognition of native governments and then entering into a treaty relationship

with them.

There were two more immediate constraints on British policy. The

disadvantages of some of the wartime agreements were becoming clear. British

ministers and officials believed that they had conceded too much to the French.

In the opinion of the General Staff, it was difficult to see how any

arrangement ‘could be more objectionable from the military point of view than

the Sykes– Picot agreement […] by which an enterprising and ambitious foreign

power [i.e. France] is placed on interior lines with reference to our position

in the Middle East’.14 There was talk of confining the French to the narrowest

possible limit of Arab land, preferably in the region of Beirut. At the same

time there was a belated appreciation of the contradictions between the various

British promises as they affected Syria and Palestine and the Zionists and

Palestinians.18

The other pressing constraint was military overstretch. In 1918 British

power in the Middle East was at its apogee. More than a million British and

imperial troops now occupied the Ottoman Empire. 19 Forces on this scale could

not be sustained for any length of time. The rapid demobilization of 1919,

however, occurred against a background of emergencies across the world,

stretching from India, via Egypt and Turkey, to Ireland, all of which were

tying up British troops. The press, led by Lord Northcliffe’s Times and Daily

Mail, believed they had found a useful stick with which to beat Lloyd George. A

Times editorial of 18 July 1921 complained that while nearly £ 150 million had

been spent since the Armistice on ‘semi-nomads in Mesopotamia,' the government

could only find £ 200,000 a year for the regeneration of British slums, and had

to forbid all expenditure under the 1918 Education Act. 20

If these weren’t handicaps enough, the continued division of

responsibility for the region between government departments was now further

exacerbated by the division of government between London and the peacemakers in

Paris. This made for endless discussion without resolution. Nor did it help

that Lloyd George had a habit of acting without reference to his advisers,

departments or prepared positions. 21

The Middle East was but one of a series of immensely complex problems

facing the peacemakers. The broad outline of the settlement in the Middle East

was not evident until the San Remo conference of April 1920. Here the British

and French effectively awarded themselves mandates over Iraq (as Mesopotamia

now came to be known), Palestine and Syria. As Curzon told the House of Lords,

the gift of mandates lay not with the League, but ‘with the powers who have

conquered the territories, which it then falls on them to distribute’. 22 It

was only at a conference of British officials and experts held in Cairo in

March 1921 and chaired by the Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, that the

question of rulers was decided, with the award of the Iraqi and Transjordanian

Thrones to two of the Sharif of Mecca,

Hussein ibn Ali of the Hashemite family’s sons, Abdullah and Faisal.

Although British policy makers saw linkages between the various

ex-Ottoman territories, there was little by way of overview of policy towards

the region, and the outcomes are best understood on a country by country basis.

Thus Faisal and the French were immediately at odds over Syria. At issue was

not simply a territorial dispute between two rival claimants, but the first

political contest between a European imperial power and a claimant standing on

the rights of self-determination. As Faisal told Lloyd George, he ‘could not

stand before the Muslim world and say that he had been asked to wage war

against the Caliph of the Muslims and now see the European powers divide the

Arab country.’ 32

With Woodrow Wilson reluctant or unable to turn his stirring rhetorical

support for self-determination into political reality, Faisal was almost

totally dependent on the British. Having committed themselves to both sides,

they equivocated and wriggled. The French prime minister, Georges Clémenceau,

who was primarily concerned with security against Germany, had little interest

in empire. In December 1918 he had been willing to agree to British control of

Palestine and Mosul, the latter with the important proviso that French

companies would have a share of oil rights there. But he assumed that Damascus

and Aleppo would be his quid pro quo. Syria was one question he could not

politically afford to concede. Strong Catholic interests were determined to

ensure that France retained its historic ‘presence’ in the Middle East, while

the war had demonstrated France’s vital interest in empire for manpower, money

and raw materials. ‘No other nation other than France’, wrote Maurice Barres in

the Echo de Paris, in a comment which would certainly not have been approved by

any official English reader, ‘possesses in so high a degree, the particular

kind of friendship and genius which is required to deal with the Arabs […] If

England wishes to give a kingdom to this Amir, let him set up in Baghdad.’ 33

Lloyd George nevertheless seemed determined to try to deny the French

their one Middle Eastern prize. His military advisers wanted a rail and air

link between Palestine and Iraq across Syrian territory for imperial

communications. Allenby warned of the risk that a French mandate would lead to

a war between France and the Arabs. Besides, the Prime Minister admired Faisal,

and believed that he had been promised at least the interior of Syria, and that

French rule would be more oppressive than British rule in Palestine and Iraq.

For much of 1919, therefore, the British tried either to reconcile the two

parties, or to get the French to change policy, and even withdraw. This led to

some furious exchanges between Clémenceau and Lloyd George. It was on one of

these occasions that Clémenceau accused Lloyd George of being a cheat. 34

In the face of French intransigence, by autumn the British opted for

France. They could no longer afford to keep an army of occupation in Syria.

Moreover, as Sir Arthur Hirtzel, Permanent Under-Secretary in the India Office,

put it, ‘If we support the Arabs in this matter, we incur the ill-will of

France; and we have to live and work with France all over the world.’ 35

British troops were withdrawn on 1 November 1919. The garrisons in Homs, Hama,

Aleppo and Damascus were handed over to Faisal, those on the Syrian littoral

went to the French. Faisal felt deserted. He complained of being handed over

‘tied by feet and hands’ to the French, insisting that Syria was ‘no more a

chattel to be used for political bargaining than is liberated Belgium.' 36

The British advised Faisal to come to terms with the French; he was

unable to do so. In March 1920 the Syrian General Congress declared the country

independent within its ‘natural boundaries’ including Lebanon and Palestine.

This earned a firm rebuke from Curzon, who pointed out firmly where power lay. ‘These countries were conquered by the Allied Armies,

and their future […] can only be determined by the Allied Powers acting in

concert.’ 37 The French were nevertheless subjected to guerrilla attacks along the

coast and denied the use of Aleppo, which was being used in support of French

troops in Cicilia fighting Mustapha Kemal. In July 1920, not very surprisingly,

the Hashemite leader was expelled. Syria, declared Alexandre Millerand, the new

French premier, would henceforward be held by France ‘the whole of it, and

forever’. 38

The loss of the direct linkage to the broader Arab hinterland that

accompanied Lebanon’s creation as a separate state (see next article), served

to strengthen the power and wealth of Beirut’s merchants and bankers, who

enjoyed a virtual monopoly on foreign trade, while smaller cities such as

Tripoli in the north and Sidon in the south, which had relied on regional,

inter-Arab trade, declined in importance economically.

British officers who had served with Faisal were deeply embarrassed to

see their former comrades ‘thrashed and trampled down’, as Churchill put it.

But there was also a certain relief that the French had extinguished the

fiercest source of agitation in the Arab world. French resentment against the

British over the affair proved long-lived. 39

If Syria had been a diplomatic embarrassment, it nevertheless proved

much less of a political headache than Iraq, whose future became the source of

acute controversy. In 1918 Iraq was ‘a ruinously neglected semi-desert,

semi-swamp of 171,599 square miles. Its population of some three million

inhabitants was a festering agglomeration of sectarian and social rivalries.’

40 It was by far the most expensive British commitment in the Middle East. In

September 1919 there were still 25,000 British and 81,000 Indian troops in the

country, the size of the garrison partly reflecting the Turkish threat to

Mosul. But there were also inefficiencies which the press soon picked up on,

with The Times running a campaign for withdrawal. Iraq became a prominent issue

in the 1922 election; indeed, between 1920 and 1924 something like a national

debate was held over whether Britain should remain. 41 All of this worried

ministers sufficiently to come close to a decision for withdrawal. The cost of

garrisoning the country seemed out of proportion to its value.42 But Iraq was

one of Britain’s few wartime gains, and the Prime Minister was ‘on general

principles’ against a policy of scuttle.

Besides, there was the prospect of oil. The British were determined not

to continue their heavy wartime reliance on American oil. The Mosul oil fields

were regarded as potentially the biggest in the world. Imperial oil consumption

was estimated to reach 10 million tons, but Persia and the Empire would only

produce 2.5 million tons. It was therefore regarded as imperative that Britain

should obtain undisputed control of as much production as possible. 44

But if British power and influence were to be retained, therefore, three

key issues had to be resolved. Should the three former Turkish vilayets of

Basra, Baghdad and Mosul be ruled directly by Britain, or indirectly through a

nominally independent Arab ruler? If the latter, who should that ruler be? And,

most important of all, could all three be welded together as a cohesive, viable

state?

Historically the vilayets had been administered separately, with their

own valis in direct contact with Istanbul. Iraq had neither a natural capital,

a single administrative system nor a ruling class. Mosul looked more to Aleppo

and southern Turkey than to Baghdad; Basra had long-established connections

with India and the Gulf, while Baghdad was the centre

of the Persian transit trade. A unitary state, an awkward creation at best,

would have to be imposed against the wishes and traditions of the individual provinces.

In addition to the sectarian divisions previously noted, some 600,000 Kurds had

been added with the Mosul vilayet. The nearest to a common denominator was the

Arabic language, which was not however spoken by the Kurds. 44

Although there had been early talk during the war of annexing Basra, by

1918 it had become clear that, thanks to Woodrow Wilson, taking over the

country was no longer a political option. This message had not, however, got

through to the man on the spot. The Acting Civil Commissioner, Lt-Colonel

Arnold Wilson, was a determined proponent of direct rule. Wilson stands as the

Middle Eastern prototype of the British official failing to adapt to changing

times in the Middle East. Described by his biographer as a late Victorian, this

highly energetic Indian army officer was an unabashed imperialist who wanted to

see a protectorate established in Iraq. Like Cromer in Egypt, he had little

time or understanding for local nationalism. The country, as Wilson saw it, was

neither ready for self-government, nor indeed wanted it. The average Arab, as

opposed to the ‘amateur politician’ in Baghdad, he conveniently believed, saw

the future in terms of fair dealing and material and moral progress under the

aegis of Great Britain. To install ‘a real Arab government’ in Mesopotamia was

impossible; if Britain attempted to do so, ‘we shall abandon the Middle East to

anarchy’. 45

This view was not shared by the more perceptive Gertrude Bell. She was

once described as the most powerful woman in the British Empire. The fact that

there was little competition does not detract from her real accomplishments.

The first woman to take a First in Modern History at Oxford, she was a

distinguished traveller and prewar intelligence

officer in the Middle East, plus a translator of the Persian poet, Hafez. On

her death in 1925, one nationalist Iraqi paper praised ‘the true sincerity of

her patriotism, free from all desire for personal gain, and the zeal for the

interests of her country which illuminated the service of this noble and

incomparable woman’, citing her as ‘an example to all men of Iraq’. 46 Bell,

who had her ear much closer to the ground than Wilson, believed that

nationalism was gaining an unstoppable momentum. From London, Hirtzel warned

that Wilson appeared to;

be trying impossibly to turn the tide instead of guiding it into the

channel that will suit you best. You are going to have an Arab state whether

you like it or not […] it is of no use to shut one’s eyes to the main facts. We

must adapt ourselves and our methods to the new order of ideas and find a

different way of getting what we want. And again, echoing Young, ‘is it not

better to do voluntarily what one will sooner rather than later be compelled to

do?’ 47

But if more far-sighted officials did not like Wilson’s approach,

ministers were dangerously slow to impose their more realistic ideas on the

Civil Commissioner. Disagreements between departments, as also between the

British and French, along with the delay in making peace with Turkey, all

contributed to procrastination. 48

This allowed time for tribal unrest to boil over into a major revolt in

1920. Iraq was a traditionally rebellious society, with a lot of arms left over

from the Ottoman era. The immediate causes of this revolt were complex, in part

local, in part the result of nationalist propaganda emanating from Syria.

During Shia’s demonstrations against the advance of ISIS in Iraq in

1914, pitchforks, symbols of the 1920 revolt, was brandished. 49

One of the revolt’s most lasting damaging consequences was to bring the

old differences between Sunni and Shi‘a back to the surface. 50 Wilson left

Baghdad in 1920, to be replaced by Sir Percy Cox. A patient, determined and

insightful man, Cox could sit through hours of small talk, gradually steering

the conversation in the direction he wanted it to go. Faisal’s biographer

describes him as having an unparalleled knowledge of Arab affairs and ‘the rare

ability to see into the motives of people from a radically different culture’.

51 His instructions were both to appease the nationalists and preserve British

influence. He immediately implemented a policy of handing over control to a

provisional Arab government with British advisers, while continuing to exercise

an authority over Iraqi ministers which was no less real for being discreet.

The British objective, in Hirtzel’s inimitably cynical words, was ‘some modicum

of Arab institutions, which we can safely leave while pulling the strings

ourselves, something which won’t cost very much’.52

The British were looking for a king. Churchill believed that in the

Middle East, as elsewhere, British interests ‘were best served by friendship

and cooperation with the party of monarchy and tradition’. 53 But they wanted

an amenable ruler, someone content to reign but not rule. They also wanted to

avoid a political system which would provide the majority Shi‘a population, who

were hostile to the British, with a political majority.54

Faisal’s new kingdom

Faisal’s new kingdom comprised all three of the former Turkish vilayets

which had come under British occupation, following Force D’s advance from Basra

in early 1915. In Arnold Wilson’s prescient view, these would not form a

coherent political entity. The Kurds would never accept an Arab ruler, nor

would the Shi‘a majority accept domination by the Sunni minority.

Three-quarters of the country, moreover, was tribal without a previous

tradition of obedience to any government. Also, there was the Jewish community

which dominated the commercial life of Baghdad, and a substantial Christian

community, including the Nestorian-Chaldean refugees from Turkey, the

Assyrians, who had gathered in Mosul.

Although alternatives were proposed – Lawrence at one point suggested

separate Emirates for Baghdad and Basra – the main British debate had been

whether to include Mosul in the new state. The problem was its predominantly

Kurdish population. Under the Treaty of Sèvres,

signed in August 1920, the Kurds had initially been promised autonomy. Opinion

at the Cairo conference as to whether to include Mosul was divided, with a

strong feeling that Kurdistan should not be brought under an Arab government

and should even be made into a buffer between Iraq and a resurgent Turkey. The

issue was also hotly contested in parliament and in The Times. But if Mosul was

to be independent, Iraq’s future was economically and strategically

compromised. Mosul was essential to Iraq not just for its oil potential, but

also as an important grain-growing area, as well as rendering the rest of the

country militarily much more defensible. In the end the economic and strategic

factors were judged as outweighing this important further addition to Iraqi

heterogeneity.

Palestine raised the even more tricky question of whether to confirm

wartime policy. The risks were now becoming more evident. In June 1919, the

Military Administrator, Sir Arthur Money, warned that fear and distrust of

Zionist aims was growing daily and that a British mandate on the lines of the

Zionist program would require the indefinite retention of a military force

considerably greater than those currently in the country. When Gertrude Bell

visited Palestine in the autumn, she found that Zionism was virtually the only

subject of discussion in Jerusalem.

All the Moslems are against it and furious with us for backing it and

all the Jews are for it and equally furious with us for not backing it enough

[…] I believe that if both [sides] would be responsible they would be each of

them have not very much to fear. But they won’t be reasonable, and we are

sowing the seeds of secular disturbance as far as I can see.

The first riots occurred in April 1920. Yet neither warnings from those

on the spot, nor the calls from the Northcliffe press to drop responsibility

for Palestine, nor even the doubts of the Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, who

believed that Palestine would prove ‘a rankling thorn’ in the flesh of the

mandatory power, led to a reversal of policy. There was still the hope that

Jewish– Arab tensions would diminish over time, not least once the economic

advantages of Jewish immigration became clear. If Britain gave up the mandate,

the French and Italians might step in. Besides, a public commitment had been

made, which the government felt honour-bound to

fulfil. Any retreat would, in Lloyd George’s words in 1921, ‘damage Britain’s

reputation in the eyes of the Jews of the world’.

The Balfour Declaration (more about this in an upcoming three part

article) was duly written almost verbatim into the preamble to the mandate,

which alluded specifically to ‘the historical connection of the Jewish people

with Palestine’. Britain was obliged to secure the new Jewish homeland and use

its best endeavours to facilitate Jewish immigration

and encourage Jewish settlement of the land. Hebrew was recognized as an

official language and a Jewish Agency established to cooperate with the

mandatory authorities in the development of natural resources and the operation

of public works and utilities. The mandatory award made no reference to the

Arabs. In contrast to the Iraqi mandate, the British were invested with full

power of legislation and administration. There was, in other words, no

obligation for the British to ensure self-government, which could only have

been on the basis of an Arab majority.

Geographically, however, in addition, the

newly mandated Palestinian territory was considerably smaller than the Zionists

had hoped. The borders, as agreed with the French in December 1920, cut the

country off from all its most important potential water resources, including the

Litani, the northernmost sources of the Jordan, the

spring of Hermon and the greater part of the Yarmuk

rivers. They also left Palestine without natural geographical frontiers, a

problem which was to have major repercussions when Israel gained independence

also, the territory to the east of the River Jordan was hived off to an Arab

ruler.

Mosul and the importance of

Oil.

In the midst of the discussions before the Inter-Allied Commission on

Mandates in Turkey left, on February 15, 1919, Clemenceau even proposed a quid

pro quo to Lloyd George. France would agree to scrap Sykes-Picot and formally

cede both Mosul and Palestine, so long as Britain would give France the mandate

for greater Syria and a quarter of the oil production of Mosul, which would be

brought to market via pipelines to be constructed in French Syria. Lloyd

George, unwilling to give up the Faisal card yet, refused to yield.

However then, forwarded on 20 March to the Political, Economic and

Military Sections of the Delegation, Sir Louis Mallet of the Foreign Office and

Sir Arthur Hirtzel of the India Office, the Intelligence Department of the

Naval Staff produced a report on Middle Eastern oil, arguing that control of

Mosul and its oil should be a British objective.

A detailed description of the prospects of finding oil in this region

was given. Most of it had yet to be surveyed, but there were good reasons to

think that it was a single oilfield, split by the Turkish-Persian frontier.

There was thought to be oil close to Baghdad as well as around Mosul. As the

Persian and Mesopotamian oilfield was a single structure, it should be

developed as such. In Persia British rights were well established; the

situation in Iraq was less clear-cut. Political stability in Mesopotamia was

required with a government that was friendly, or at least neutral, towards

Britain.

Thus after the war, Britain had several reasons to want the League of

Nations mandate over Iraq, but oil was the main reason why it wanted Mosul to

be part of Iraq. France, Italy, and the USA were all also interested in Mosul's

oil.

A British controlled concession in Turkey was not as good for Britain as

oil in Iraq. It was more important that oil should be in territory controlled

by or friendly to Britain than that concessions should belong to British

companies. Archival evidence shows that oil motivated Britain's desire that

Mosul should remain part of Iraq.

Various disagreements delayed an Anglo-French oil agreement, but one was

finally signed at San Remo in 1920. It was followed by the Treaty of Sèvres with the Ottoman Empire, which appeared to give

Britain all that it wanted in the Middle East.

The resurgence of Turkey under Mustafa Kemal meant that a new treaty had

to be negotiated at Lausanne in 1923. Serves angered the USA since it appeared

to exclude US oil companies from Iraq. For a period Britain focused on the need

to have a large British controlled oil company, but it was eventually realized

that control of oil bearing territory was more important than the nationality

of companies. This allowed US oil companies to be given a stake in Iraqi oil,

improving Anglo-American relations.

Britain's need for oil also meant that it had to ensure that the Treaty

of Lausanne left Mosul as part of the British mandate territory of Iraq. Turkey

objected, but the League of Nations ruled in Britain's favor. Britain had other

interests in the region, but most of them did not require control over Mosul.

Mosul's oil gave Britain secure supplies and revenue that made Iraq viable

without British subsidies.

The British had managed to camouflage the oil issue during their

campaign in the League of Nations for Mosul to be attached to Iraq – a claim

hotly contested by the Turks – by making their case on ethnic grounds. Having

been awarded Mosul, the Iraqis were pressured into making the oil concession by

holding it as a precondition for the election of Iraq’s first parliament. But

with the Americans determined to prevent Britain from establishing a monopoly,

London failed to obtain a majority shareholding in the company for British

national groups. ‘We shall probably have to let in the Americans somehow’, one

official had written in 1921. ‘But we should prefer to do it as an act of grace

rather than by compulsion.’

Britain nevertheless exerted a considerable influence over the company

by virtue of the fact that it was registered in Britain and had a British

chairman.

Iraqi willingness to accede to so many demands reflected the

government’s heavy dependence on British assistance, most notably for security.

The ‘sheet anchor’ of British power lay not in the threat to intervene

militarily, but rather, as Dobbs noted, to withhold military intervention.

There was constant trouble in the southern provinces and in Kurdistan. Until

the final settlement of the Mosul dispute in 1925, the northern province was

threatened by Turkish irregular units. In the south-west, Ikhwan raiding from

Ibn Sa’ud’s kingdom of Najd continued on and off for

seven years. This desert war, which had begun in 1924, reflected one of the

difficulties of translating European notions of sovereign states with fixed

frontiers into a region of nomadic tribes, whose very existence depended on

their ability to migrate and graze freely. But the early raids also reflected

the deep-seated hostility between Ibn Sa’ud and the

Hashemites.

The key to controlling these various conflicts was airpower. Lawrence

had believed that aircraft ‘could rule the desert’. Despite early technical

problems, a political coalition between the RAF, anxious for a peacetime role

to justify its continued existence as an independent service, and the

politicians, led by Churchill, desperate to reduce costs in Iraq, ensured that

air power became a covert means of pursuing empire in an increasingly

anti-imperial age. The Colonial Secretary was perhaps the only minister willing

to gamble on turning such a large state over to a new, and still largely

untried, method of imperial control. First deployed in the early 1920s, it

became the main British instrument for ensuring order until Iraqi independence

in 1932. Its value to the insecure, fledgling Iraqi government is attested by

the fact that between August 1921 and 1932, the RAF came to the government’s

aid on 130 occasions.

Its long-term value to the British was also substantial. Iraq provided

the RAF with operational training and a distinctive role. In his study of air

power and colonial control, David Omissi credits Iraq

with facilitating the independent survival of the Service, which had only been

formed in 1918 and still faced opposition from the navy, army and Treasury,

thereby helping ensure British victory in the Battle of Britain in 1940. The

Iraqi experience also lies behind the strategic bombing campaign of World War

II, affording the RAF, including the future head of Bomber Command, Air Chief

Marshall Sir Arthur Harris, with their only significant experience of bombing

prior to 1939. Airpower was cheap, quick, flexible, and ideally suited to a

large country with poor communications. It was particularly effective against

tribal dissidence and border encroachments, while allowing control of remoter

regions without the expense of occupation. Warnings were normally given and,

according to at least one officer, aircraft did not generally inflict very

heavy casualties, but achieved a moral effect by engendering a feeling of

helplessness among tribesmen unable to reply effectively to attack.

Squadron-Leader Harris, as he then was, wrote however that both Arabs and Kurds

knew that ‘within 45 minutes a full-scale village can be practically wiped out

and a third of its inhabitants killed or injured’. Despite official

instructions, air control was also used to enforce revenue collection,

sometimes becoming a substitute for good administration. It was quicker and

easier to send aircraft than to investigate disputes and grievances on the

ground. Similarly it was easier to bomb the Kurds than make political

concessions to them. Either way air control did not encourage the Iraqi government

to develop more peaceful means of extending control over its territory. But Leo

Amery’s verdict of 1925, that were the aeroplane

‘removed tomorrow, the whole [Iraqi] structure would inevitably fall to

pieces’, appears to have been close to the mark.

Iraq, however, needed forces of its own; according to the 1922 treaty,

it was to take over responsibility for internal security and national defense

within four years. Faisal wanted to introduce conscription, but the British

objected, preferring the creation of a small, professional mobile army.

Conscription promised poorly trained troops and threatened to divert funds from

roads and railways essential to Iraqi development and British military mobility

in the country. But there were two other reasons for the British opposition. A

large army could become the instrument of a government with despotic

aspirations. The other touched on one of the basic weaknesses of the new

country. Whereas Faisal looked to conscription as a means of nation building,

the British realized that it would be highly unpopular with the majority Shi‘a

community; they had no wish to become involved in any consequent enforcement

activities for which they would then be blamed. The Iraqis suspected the real

reason for British objection was that they did not want a strong Iraqi army. In

addition to security, mandatory Iraq also needed British financial help and, at

least in the early years, administrative expertise. According to de Gaury,

ministers depended on the advisers for unbiased opinions and hard and quick

work. While the numbers of British advisers more than halved between 1923 and

1931, they nevertheless proved a potent source of Anglo-Iraqi friction. Stephen

Longrigg, who was Inspector-General of Revenue, later

wrote of ‘an adolescent society and government impatient to be rid of foreign

control, condescension, and wiseacre advice, which its politicians never wholly

trusted and frequently misunderstood’.

Every order and measure within a ministry had to pass through the

Adviser before gaining ministerial signature. If the Adviser objected because

it was contrary to the treaty or good administration, the matter was raised

with the High Commissioner, who in extreme cases ‘advised’ the King against it.

A special Iraqi term, al-Wadha al-Shadh, translated

as ‘perplexing predicament,' was invented to describe this much-resented system

of dual responsibility.

As in Egypt, the High Commissioner would at times intervene over the

appointment of ministers. Cabinets, therefore, tended to be dominated either by

conservative elements or by young Iraqis willing to work with Britain. Iraqis

coined the sarcastic epithet Mukhtar dhak al-Saub for the High Commissioner,

loosely translated as boss on the other side of the River Tigris from the prime

minister’s residence. Iraqi frustration with the mandate was captured by the

poet, Ma’ruf al-Rasafi:

He who reads the Constitution will learn that it is composed according

to the Mandate He who looks at the flapping banner will find that it is

billowing in the glory of aliens He who sees our National Assembly will know

that it is constituted by and for the interests of any but the electors He who

enters the Ministries will find that they are shackled by the chains of foreign

advisers.

Much to Dobbs’s annoyance, Faisal was

constantly trying to chip away at British privileges, to the point that by 1928

the two men could barely tolerate being together. Faisal’s aim, however, was

not complete British disengagement, something he knew he could not afford, but

an end to the High Commissioner’s interventions in Iraqi internal affairs. The

British were partially responsive. They could not afford a discontented Iraq

and recognized the growing risk that the continuation of the mandate would

undermine Faisal’s credibility on which they ultimately depended, so were,

therefore, willing at least to loosen their control. But a new treaty in 1927

failed to provide the concessions Faisal wanted. Two years of haggling and one

tragedy followed. In 1929 the Iraqi prime minister, ‘Abd al-Muhsin al-Sa’adoun, committed suicide. In the note he left for his

son, he wrote that the Iraqis ‘are weak, powerless and far from independence.

They are incapable of accepting the advice of honorable people such as I. They

think I am a traitor to the country and a slave of the English.’

The treaty, which was eventually signed in 1930, provided for de jure if

not de facto Iraqi independence. Britain retained two rent-free air bases,

which were relocated away from Baghdad and Mosul to reduce friction with

nationalist circles. There would be mutual help in time of war, including the

right to transport troops across Iraq. Iraq would continue to buy military

equipment from Britain, employ at its expense the services of the British

military mission, and send its officers exclusively to British military

academies. There was to be ‘full and frank’ consultation on all foreign policy

questions concerning their common interests. Iraq should normally employ

Britons in posts held by non-Iraqis, thus continuing to give Britain

considerable latitude in defense and administration. Britain, however, ceased

to have any responsibility in internal affairs, which meant that the RAF would

no longer help with internal security. The High Commissioner became an

ambassador, though with a higher status than that of other foreign envoys.

Close contacts with the government continued. As of September 1932, the

ambassador paid at least one weekly visit to the King, while the Prime Minister

normally paid a weekly visit to the embassy.

Iraq had agreed to these terms because it wanted admission to the League

of Nations, as well as the assurance of continued British military support

against external attack. The treaty, nevertheless, met with widespread

opposition. Many Shi‘a feared that independence was a prolog to mass

conscription; Kurds feared subordination in a predominantly Arab state. The

League of Nations had for some time been uneasy about Iraq’s intolerant policy

towards its minorities. When the League had awarded Mosul to Iraq in 1925, it

had demanded a 25-year Anglo-Iraqi treaty, as a means of guaranteeing Kurdish

rights. Dobbs had once described the Kurds as ‘the sheet-anchor’ of British

influence in Iraq. There was also concern about the positions of the Assyrians,

a Christian group who had come from Turkey after World War I. Many served in

the Levies, an imperial rather than an Iraqi force, which the British regarded

as more efficient and reliable than the Iraqi army, and which were used to

guard the RAF bases. British attempts to intervene with the Iraqi government on

behalf of both minorities were consistently rebuffed, a fact which the British

were anxious to conceal from the League of Nations Permanent Mandate

Commission. This cover-up allowed Iraq to become the first mandatory territory

to be admitted to the League of Nations. For the Iraqis, it was an important

symbol of equality. To French displeasure, it also provided a potential

precedent for Syria and Lebanon.

The mandatory period of Anglo-Iraqi relations had lasted barely more

than a decade. The British had provided a ruler, parliament, and a

Western-style constitution. They had provided the government and country with

vital security and helped with the establishment of an administration. They had

also helped ensure that Mosul, where oil was found in 1928, remained Iraqi. But

they had not provided significant resources for economic development. In Iraq,

as elsewhere in the Middle East, the Treasury was ungenerous. There had been a

minimal investment in education because it would be dangerous to educate young

people who would have no prospects for employment. In 1932 there were fewer

than two thousand secondary school places in Iraq.

Nor had the British helped to provide their awkward creation with

something even more important, namely a political culture which might allow it

to transcend its multiple divisions; indeed to some extent the British had

hindered this development. Since Iraqis were never given real responsibility in

government and regarded the constitution as an instrument of foreign control

and manipulation, the constitution never took root. Parliament was not

representative of the country as a whole, but rather of those groups, notably

the tribal sheiks, whom the British had sought to bolster, while the government

was conducted for the benefit of the Sunni urban elite. In 1937 the British

ambassador described elections as a ‘dumbshow.' This undemocratic distribution

of power could only serve to deepen the ethnic and religious divisions which

Iraq had inherited.

Sir Henry Dobbs had few illusions. ‘My hope,' he had written in

retirement in 1929;

is that, even without our advice, Iraq may now be so well established,

that she may be able to rub along in a corrupt, inefficient, oriental sort of

way, something better than she was under Turkish rule […] If this is the

result, even though it may not be a very splendid one, we shall have built

better than we knew.

He was over-optimistic. The end of the mandate was followed by a period

of instability, with religious and ethnic groups asserting their claims to

greater autonomy, renewed tribal unrest in the south and a distinct sense of

disillusion with the constitutional system. Between 1936 and 1941 there were no

less than seven military coups.

The 1930s saw a notable decline in British influence, and one senior

British official complained, the treaty failed to ‘bring us the credit of

friendship we might have acquired by leaving Iraq altogether – but at the same

time – did not bring us power and control which we set out to secure’. Faisal

died in 1933. Despite being educated at Harrow, and having a taste for Savile

Row suits, the young King Ghazi, who, like Farouk in Egypt, was very much the

playboy prince, strongly resented British influence. In July 1936 the Foreign

Office was considering forcing his abdication. The following year he opened a

radio station, a gift from Hitler, in his palace. It attacked Zionism and

British influence in the Gulf. His death in a drunken road accident in 1939 was

widely attributed to the British; a theme played up by German radio. Ghazi’s

views were representative of a younger nationalist generation, who resented the

lack of full independence, and were influenced by the Arab revolt in Palestine.

They saw the British as an obstacle to Arab unity and looked to European

fascism as a successful new social model. Fascist ideas had a particular appeal

among young army officers, who disliked continued British control and saw

Germany as an example of how the army could become a ‘school for the nation’

and a vanguard of liberation from colonialism. Alignment with the Axis offered

a means of liberating Iraq from dependence on Britain.

Arms supplies were a particular bone of contention. Under the 1930

treaty, Britain was obliged to sell the modern arms the Iraqis needed. But the

requests made in the 1930s were not all met. In 1936 the Foreign Office was

chary of a proposal to double the Iraqi air force, making it superior in

numbers and quality to the RAF. The main problem, however, was the slow pace of

the British rearmament. The Iraqis could not believe that a Great Power would

be unable to supply their needs and suspected that they were deliberately kept

short of arms. The delivery of German and Italian weapons in 1937, in clear

breach of the 1930 treaty, facilitated Axis penetration of the armed forces.

Senior Iraqi military figures visited Germany, establishing ties with German

firms. Indeed by the mid-1930s, the German minister, Fritz Grobba,

who had a good command of Arabic and Turkish and a deep knowledge of the

region, was beginning to take on the social and political role once played by

the British embassy. A British embassy report of April 1939 spoke of the

Germans ‘pouring money’ into Iraq. The ambassador, Sir Maurice Peterson, found

himself powerless to do much more than issue warnings to the Iraqis.

The 1930s also witnessed the emergence of another problem which was to

cause considerable trouble in future years. Following independence, Iraq laid

claim to neighboring Kuwait. It did so on the basis that it was a successor

state to the Ottoman Empire and of the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, which

had stipulated that Kuwait was an autonomous district of the Empire and the

sheik an Ottoman official. This was despite the fact that the convention had

remained unratified, that Turkey had renounced all claims under the 1923 Treaty

of Lausanne, and that Iraq had in 1932 accepted the Iraqi-Kuwaiti border. The

Iraqis pursued their case by a propaganda campaign, support for dissident

elements in Kuwait and border incursions. All this was successfully opposed by

Britain, which was responsible for the defense of Kuwait, and was already

eyeing the sheikhdom as an alternative should they lose their Iraqi bases. But

opposition came at the cost of further undermining Britain’s position in Iraq.

The Arab question and the ‘shocking document’

that shaped the Middle East.

Showing things were not going to well, Britain’s defeat at Gallipoli was

followed by an even more devastating setback in the war against the Ottomans:

The Menace of Jihad and How to Deal with It.

French rivalry in the Hijaz; the British attempt to get the French

government to recognize Britain’s predominance on the Arabian Peninsula; the

conflict between King Hussein and Ibn Sa’ud, the

Sultan of Najd; the British handling of the French desire to take part in the

administration of Palestine; as well as the ways in which the British

authorities, in London and on the spot, tried to manage French, Syrian, Zionist

and Hashemite ambitions regarding Syria and Palestine. The

‘Arab’ and the ‘Jewish’ question.

The British authorities in Cairo, Baghdad and London steadily lost their

grip on the continuing and deepening rivalry between Hussein and Ibn Sa’ud, in particular regarding the possession of the desert

town of Khurma. British warnings of dire consequences

if the protagonists did not hold back and settle their differences peacefully

had little or no effect. All the while the British wanted to abolish the Sykes–

Picot agreement. The Syrian question.

One of the most far-reaching outcomes of the First World War was the

creation of Palestine, initially under Britain as the Mandatory, out of an

ill-defined area of the southern Syrian boundary of the Ottoman Empire. The

true history of the Balfour Declaration and its implementations P.1.

The true history of the Balfour Declaration and

its implementations P.2.

The true history of the Balfour Declaration and

its implementations P.3.

1. Christine Riding, ‘Travellers and Sitters:

The Orientalist Portait’, in Nicholas Tromans and Rana Kabbani (eds), The Lure of the East

(London, 2008), p. 61.

2. D. K. Fieldhouse, Western Imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958,

2008, p. 69.

3. Eleanor H. Tejirian and Reeva Spector

Simon, Conflict, Conquest, and Conversion: Two Thousand Years of Christian

Missions in the Middle East, 2012, p.183.)

4. Not mentioned in the London Gazette: see both censored and uncensored

versions of Allenby’s report for the London Gazette, preserved in PRO, WO 32/

5128.

5. Cited in James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the

Struggle That Shaped the Middle East, 2011, 61– 62.

6. Cited in David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the

Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, 2001, 377.

7. Christopher Catherwood, Churchill’s Folly (New York, 2004), p. 119.

8. Margaret MacMillan, Peacemakers: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919

and Its Attempt to End War,2001, p. 392.

9. Henry Foster, The Making of Modern Iraq (London, 1936), p. 87.

10. Ephraim and Inari Karsh, Empires of the Sand (Harvard, 1999), p.

261. Helmut Mejcher, Imperial Quest for Oil: Iraq,

1910– 1928 (London, 1976), p. 177.

11. John Marlowe, Late Victorian: The Life of Sir A. Talbot Wilson

(London, 1967), p. 134.

12. Macmillan, Peacemakers, p. 297.

13. Shareen Blair Brysac and Karl E. Meyer,

Kingmakers: The Invention of the Modern Middle East, p. 144.

14. D. K. Fieldhouse, Western Imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958,

2008, p. 69.

15. Peter Sluglett, ‘An Improvement on

Colonialism? The “A” Mandates and their Legacy in the Middle East’,

International Affairs, March 2014, p. 414.

16. British Documents on Foreign Policy, Vol. xiii (London, 1963), p.

264.

17. Erik Goldstein, British peace aims and the eastern question: the

political intelligence department and the Eastern Committee, 1918, Middle

Eastern Studies,Volume 23, 1987 - Issue 4, p. 424.

18. John Darwin, Britain, Egypt and the Middle East (London, 1981), p.

134. British Documents on Foreign Policy, Vol. iv, p. 343.

19. David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle

East, 1914-1922, 1990, p. 385.

20. Ibid., p. 470. Christopher Catherwood, Churchill’s Folly: How

Winston Churchill Created Modern Iraq, 2004 p. 72. John Townsend, Proconsul to

the Middle East (London, 2010), p. 182.

21. Briton Cooper Busch, Britain, India and the Arabs, 1914-21,1971 pp.

272– 3.

22. Macmillan, Peacemakers, p. 416.

23. Arab Buttetin, June 23,1916, p. 47 &

Feb. 6,1917, pp. 57-58, FO 882/25. See also McMahon to Grey, Ocr. 20, 1915, British Foreign Office (FO) 371/2486/154423;

"Intelligence Report," Dec. 28,1916, FO 686/6, p. 176.

24. Hussein to McMahon (Cairo), July 1915-Mar. 1916, presented to

British parliament, Cmd. 5957, London, 1939, P: 3 (hereinafter -

"Hussein-McMahon Correspondence"). 64.

25. Hussein's letter of Nov. 5,1915, ibid., P' 8; McMahon's letter of

Dec. 14, 1915, ibid., pp. 11-12; "Report of Conversation between Mr. R.C

Lindsay, ev.a., Representing the Secretary of State

for Foreign Affairs, and His Highness the Emir Faisal, Representing the King of

the Hedjaz. (Held at the Foreign Office on Thursday, Jan. 20, 1921)"

British Colonial Oficce (CO) 732/3, fol. 366.

26. For the text of Hussein's letter, see Times, May 19, 1923. See also

Husseini's letter to High Commissioner Samuel, Nov. 3, 1923, Central Zionist

Archives (CZA), 525/10690.

27. B. H. Liddell Hart, T. E. Lawrence to his Biographer (London:

Cassell, 1962), P: 142 (recording a conversation with Lawrence, Aug. 1, 1933).

28. Abu Khaldun Sati al-Husri, Yawrn Maisalun: Safha min Tarikh al-Arab al-Hadith (Beirut: Dar al-Ittihad,

1964, rev. ed.), p. 261.

29. Jamal Husseini, "Report of the State of Palestine during the

Four Years of Civil Administration, Submitted to the Mandate's Commission of

the League of Nations Through H.E. the High Commissioner for Palestine, by the

Executive Committee of the Palestine Arab Congress - Extract," Oct.

6,1924, p. 1, 525/10690 (CZA); "Minutes of the JAE Meeting on Apr. 19,

1937," BGA (Ben Gution Archive); "The Arabs

Reject Partition," quoted from Palestine & Transjordan, Vol. II, No.

57 (july 17, 1937), p. 1, S25/10690.

30. General Nuri Said, Arab Independence and Unity: A Note on the Arab

Cause with Particular Reference to Palestine, and Suggestions for a Permanent

Settlement to Which Are Attached Teas of All the Relevant Documents (Baghdad:

Government Press, 1943), p. 11.

31. "First Conversation on Trans-jordania,

Held at Governmem House, Jerusalem, Mar. 28,

1921," FO 371/6343, fols. 99-101; "Second

Conversation on Trans-jordania” & "Third

Conversation on Trans-jordania," ibid., fols. 101-02.

32. Ali A. Allawi, Faisal I of Iraq, 2014, p. 249.

33. Ibid., p. 253. Howard M. Sachar, Emergence of the Middle East,

1914-24,1970, pp. 259– 60.

34. Jukka Nevakivi, Britain, France and the

Arab Middle East, 1914-20 (University London Historical Study),1969, p. 154.

Busch, Britain, India, p. 313. Bell, France and Britain, Vol. i, pp. 126– 7. Paris, Britain, the Hashemites, p. 62.

35. Ibid., p. 55. James Barr, Setting the Desert on Fire: T.E. Lawrence

and Britain's Secret War in Arabia, 1916-18, 2007, pp. 165, 302.

36. Nevakivi, Britain, France, p. 208. Elie Kedourie, England and the Middle East: Destruction of the

Ottoman Empire, 1914-21, 1987, p. 148.

37. Allawi, Feisal, p. 276.

38. Fromkin, Peace to End, pp. 436– 9.

39. Nevakivi, Britain, France, p. 256. William

Jackson, Britain’s Triumph and Decline in the Middle East (London, 1996), p.

15.

40. Sachar, Emergence, p. 376.

41. Townshend, When God Made Hell, pp. 454, 514– 16. John Marlowe, Late

Victorian: The life of Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson,1967, pp. 162– 4. John

Townsend, Proconsul to the Middle East: Sir Percy Cox and the End of Empire,

2010, p. 183.

42. Kwasi Kwarteng, Ghosts of Empire (London, 2011), p. 25.

43. Nevakivi, Britain, France, p. 91. Mejcher, ‘Oil and British Policy towards Mesopotamia’, pp.

384– 5. Catherwood, Churchill’s Folly, pp. 75, 205.

44. Peter Sluglett, Britain and Iraq (London,

2007 edn), p. 45. Fieldhouse, Western Imperialism, p.

70.

46. Busch, Britain, India, p. 356. Marlowe, Late Victorian, pp. 136– 7,

170, 255– 6.

47. Justin Marozzi, Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood,2016, pp. 290–

1, 304.

48. Ibid., pp. 165– 6. Charles Tripp, A History of Iraq (Cambridge,

2000), p. 39.

49. Ibid. Marlowe, Late Victorian, p. 125. Stephen Hemsley Longrigg, Iraq, 1900 to 1950: A political, social, and

economic history (London, 1953), p. 118.

50. Darwin, Britain, Egypt, p. 200. Sachar, Emergence, p. 373. Eugene

Rogan, The Arabs: A History,2011, p. 173. ‘Top Shi‘a Cleric Piles Pressure on

Maliki’, Financial Times, 21 February 2014.

51. Marozzi, Baghdad, p. 299.

52. Allawi, Feisal, p. 384. Marlowe, Late Victorian, p. 256.

53. Ibid., p. 183, Busch, Britain, India, p. 423, Darwin, Britain,

Egypt, pp. 215– 16.

54. David Cannadine, Ornamentalism: How the

British Saw Their Empire, 2002, p. 75.

For

updates click homepage here