By Eric Vandenbroeck

The Imprisonment of Hundreds of

Wealthy Saudis

As is known, Saudi Arabia’s ascendant crown prince, Mohammad bin Salman

(MBS), on Saturday swept aside dozens of potential

rivals in a series of arrests and firings on Saturday to impose a centralized

system that can confront what is perceived as the Iranian threat.

There are countries in which you are accused of an act of corruption and

then you are arrested. And then there are countries in which someone decides to

arrest you and only then are you called corrupt. Thus those who know the

country have argued that these arrests are indeed part of the indicated major

political transition, which by default is an assault on the country’s

sclerotic, traditional power structure.

The very same day Houthi rebels launched a missile from Yemen toward

the King Khaled Airport, north of Riyadh.

MBS’ consolidation of power has come with the implicit support of the

Trump administration. He has cultivated a close relationship with Jared

Kushner; David Ignatius reports that, during Kushner’s recent unannounced trip

to Riyadh, “The two princes are said to have stayed

up until nearly 4 a.m. several nights, swapping stories and planning strategy.”

Earlier in July 2017, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the UAE also cut Qatar’s external communications, presenting a thirteen-point

ultimatum that was designed to be rejected, rather like the one Austria-Hungary

sent to Serbia in July 1914. The demands included expulsion of the Muslim

Brotherhood leaders and the closure of al-Jazeera TV.

Although support from President Trump probably encouraged Crown Prince Mohammed

bin Salman down this path, ironically the Secretaries of Defense and State

rushed to protect Qatar, which is home to a huge US airbase. A history of how these problems came about has been

presented here.

Coinciding with an escalation of its conflicts abroad points to the fact

that MBS intends to use a face-off with the deeply hated Iran as a unifying

force within Saudi Arabia.

This said (see also the

Shi’ite-Suni devide) hatred towards Saudi Arabia

runs just as deep in Iran symbolized by Supreme Leader Khomeini denouncing King

Fahd as a "traitor to God" in his final testament.

Castigating the "small and puny Satans" of Riyadh or like his

successor Ayatollah Ali Khamenei who called on the Muslim world to remove Saudi custodianship of the

two holy places and the Hajj. The Saudi Grand Mufti, Sheikh Abdul-Aziz Al Sheikh,

promptly ruled that Iranians are not really Muslims but the descendants of pagan

Zoroastrians. In January 2016, the Saudis decided to include the Shia cleric

Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr among the forty-six men (most of them Al Qaeda members) it

executed. His offense was to call for the overthrow of the Sauds,

though charges of involvement in terrorism were spuriously added. After playing

a cat-and-mouse game with the authorities, Nimr was apprehended in 2012 and

sentenced to death in October 2014. Angry Iranians burned down

the only recently opened Saudi embassy in Tehran.

But Iran’s major advantage over the Gulf monarchs is that it has

developed instruments to project power. The Revolutionary Guard and its Quds

Force are battle tested and know how to share expertise and advice. Iran’s

closest allies are Hizbollah in Lebanon, the Assad

regime in Syria, the Shia government of Iraq and President Putin’s Russia. But

none of these are ‘clients’ and the notion of a ‘Shia crescent’ operating in

the region is a propaganda theme spread by the Gulf

monarchies.

Iran calculates that during the period of grace it enjoys as the

international community seeks to bed down the nuclear agreement, it can afford

to make aggressive moves, especially as Iran will have to be included in any

peace negotiations over Syria, one of the main sources of the waves of refugees

troubling Europe, Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and elsewhere. Tehran also exerts

considerable influence on Shia-dominated Iraq, seemingly able to engineer the

appointment and replacement of prime ministers through its influence on the

powerful Dawa Party.

It is also known that, among others, Iraqi militias are part of the

larger (mainly Afghan, Iraqi, Lebanese and Pakistani) Shia force that Iran has

deployed to bolster Syria’s embattled President Bashar al-Assad. So great is

Iran’s influence that it can change Iraqi strategy against ISIS. Initially

Mosul was to be enveloped in a horseshoe posture, leaving a western exit for

both refugees and fleeing ISIS fighters. Since Iran feared the latter would

debouch to Syria, where they and the Russians have turned the war there in favour of Assad, the Iranians insisted on complete

encirclement, with their proxy militias poised to turn the road west from Mosul

into a kill-box. The French government supported this

strategy since it would eliminate the terrorist commanders who in 2016 ordered

attacks in Brussels and Paris.

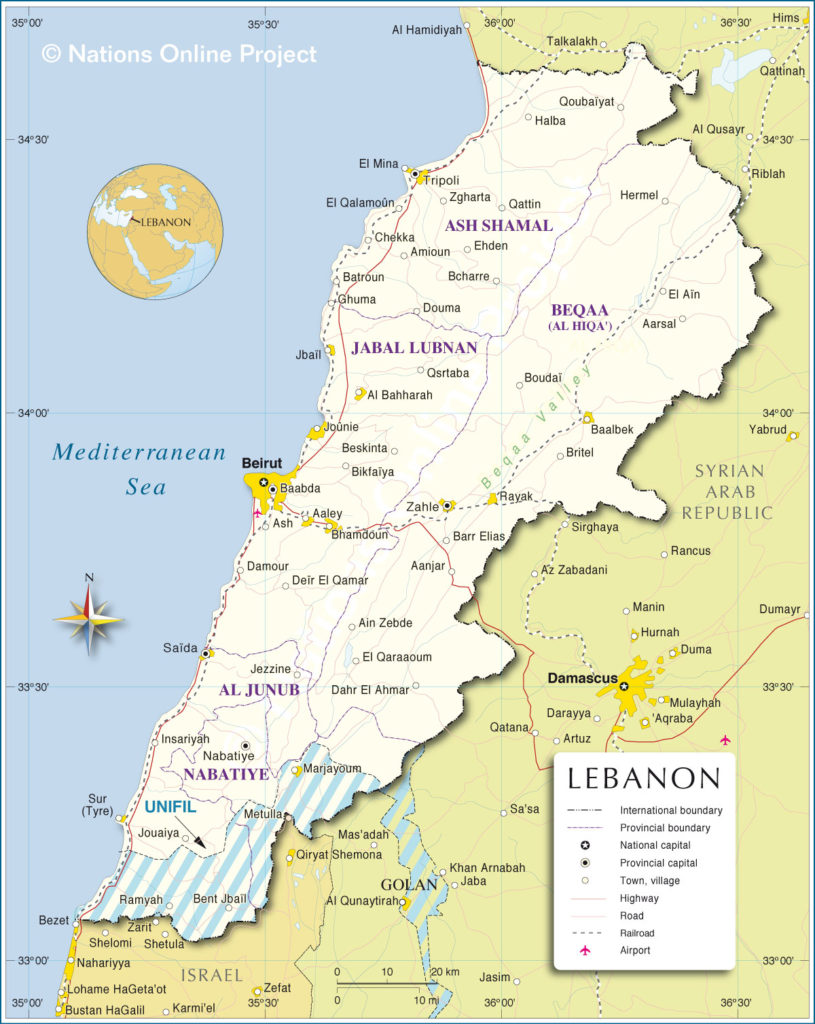

As for the current situation in Lebanon, on Saturday Lebanese Prime

Minister Saad Hariri resigned from office in a televised announcement filmed in

Riyadh. In his statement, Hariri said he was stepping down due to an

assassination plot, he may have even fled the country, only calling President

Michel Aoun after he left Lebanon. “We are living in a climate similar to the

atmosphere that prevailed before the assassination of martyr Rafik al-Hariri,”

Hariri said in his announcement. “I have sensed what is being plotted covertly

to target my life.” He also promised retribution against Iran, saying that

Lebanon and the Arab states will “cut off the hands that wickedly extend into

it.”

As I extensively covered in my overview

about Lebanon, Hariri’s resignation concludes an uncomfortable

year-long arrangement, in which he regained the prime minister’s seat in exchange for endorsing Aoun, an

ally of Hezbollah, for president. At the time, the compromise ended a

two-and-a-half-year political crisis, during which Lebanon did not

have a president, but it always made for strange bedfellows. For the past year,

Hariri has served in a government alongside Hezbollah, the group international

investigators believe to be responsible for his father’s murder. “We have an

understanding with Hezbollah,” Hariri told Foreign Policy during a visit to Washington

in July. “The functioning of the government, parliament and everything, it’s

important to have this consensus.”

Despite the obvious fragility of the arrangement, Hariri’s resignation

has been met with surprise and confusion in Beirut. Hezbollah Secretary General

Hassan Nasrallah tried to contain the fallout on Sunday by blaming Saudi Arabia for Hariri’s

resignation. “It was definitely a Saudi decision that was imposed

on him,” he said. “It was not his will to step down.” President Aoun told

reporters he won’t recognize Hariri’s resignation until he explains it in

person.

It appears that Hariri had to go because he was unwilling to confront

Hezbollah.

I also suspect that Hariri is neither a free man nor a hostage in KSA;

as per often in today’s Middle East he probably is somewhere in between with

Saudis able to impose maximum pressure on him as a Saudi citizen, and to use

him as a Lebanese politician in the fight against Iran and Hezbollah.

According to analysts, Saad Hariri’s resignation as Lebanese prime

minister could lead to an extended crisis in

the country with neither Iran nor Saudi Arabia achieving their

preferred outcomes.

At a minimum, Hariri’s resignation means a competition for leadership of

Lebanon’s Sunni community and a delegitimized government tilted towards

Hezbollah. Elias Muahanna, an insightful observer of

Lebanese politics, notes that Saudi Arabia could try

to isolate Hezbollah and Lebanon the way it has Qatar, leading a boycott of the

country and potentially cutting off lucrative business contracts between Saudi

and Lebanese companies. But it could also be much more destabilizing than that.

Lebanon, though racked with intermittent violence and overwhelmed by refugees,

has remained surprisingly stable over the past several years, despite the civil

war next door. A Saudi-backed clash with Hezbollah, though, could dissolve that

semblance of stability, and with the conflict in Syria winding down, Sunni

militants could shift their attention west, setting the stage for more violence

in a different theater. The New York Times reported that on Sunday Bahrain warned

its citizens to leave the country, which could be a worrying sign.

“Less than a year after Saad Hariri

re-entered office, his departure raises fears that Lebanon is being dragged

anew into the dangerous crosswinds of the Saudi-Iranian rivalry,” wrote Julien Barnes-Dacey,

a senior Middle East policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign

Relations, on Tuesday.

More to the point, an FP contributor in an article yesterday, titled

“Jared Kushner, Mohammed bin Salman, and Benjamin Netanyahu Are Up to

Something” suggests that not only the Saudi’s but also Israel might prepare for

another war with Hezbollah in Lebanon, preparations which have already been

in the works for some time.

On 5 November, Tel Aviv started the largest-ever aerial exercise in the history of Israel.

Shortly after Hariri announced his resignation, Israel’s defense

minister, Avigdor Lieberman, took to Twitter. “Lebanon = Hezbollah. Hezbollah =

Iran. Iran = Lebanon,” he wrote. “Iran endangers the world. Saad Hariri has proved that today.

Period.”

The recent leak of a classified Israeli Foreign

Ministry cable sent to all Israeli diplomatic facilities worldwide

points to the subterfuge being engaged in by Israel and Saudi Arabia to

effectuate political discord in Lebanon and a Saudi military confrontation with

Iran.

Thamer al-Sabhan, the Saudi minister for Gulf

affairs, said on Monday that Lebanon’s government would “be dealt with as a government declaring war on

Saudi Arabia” because of what he described as “acts of aggression”

committed by Hezbollah.

As for the missile from Yemen toward the King Khaled Airport, the

Houthis have fired rockets into the kingdom before, but previous attacks have

mostly been concentrated along the Saudi-Yemeni border. The Yemeni missile, a

new Scud variant likely developed with

the help of Iran, puts Saudi Arabia at much greater risk of attack.

Both Trump and Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister, Adel al-Jubeir,

have pinned responsibility for the attack on Iran, though the head of Iran’s

Revolutionary Guards denied involvement. “We do not have even the possibility

to transfer missiles to Yemen. The missiles belong to them and they have

increased their range,” Mohammad Ali Jafari told Iranian state media. Saudi

Arabia retaliated by tightening its grip on Yemen, closing off the Saudi-Yemeni

border and blocking sea and air traffic. And charging Iran with an “act of war”

thus raising the threat of a military

clash.

Why Tehran Is Winning the War

for Control of the Middle East

In Lebanon, Hezbollah vanquished

the Saudi-sponsored “March 14” alliance of political groups that

aimed to constrain it. The events of May 2008, when Hezbollah seized west

Beirut and areas around the capital, showed the helplessness of the Saudis’

clients when presented with the raw force available to Iran’s proxies. Hezbollah’s

subsequent entry into the Syrian civil war confirmed that it could not be held

in check by the Lebanese political system.

The establishment of a cabinet dominated by Hezbollah in December 2016,

and the appointment of Hezbollah’s ally Michel Aoun as president two months

earlier, solidified Iran’s grasp over the country. Riyadh’s subsequent

withdrawal of funding to the Lebanese armed forces, and now its push for

Hariri’s resignation, effectively represent the House of Saud’s acknowledgement

of this reality.

In Syria, Iran’s provision of finances, manpower, and know-how to the

regime of President Bashar al-Assad has played a decisive role in preventing

the regime’s destruction. The Iranian mobilization of proxies helped cultivate

new local militias, which gave the regime access to the manpower necessary to

defeat its rivals. Meanwhile, Sunni Arab efforts to assist the rebels, in which

Saudi Arabia played a large role, ended largely in chaos and the rise of Salafi

groups.

In Iraq, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has developed an

officially-sanctioned, independent military force in the form of the

120,000-strong Popular Mobilization Units (PMU). Not all the militias

represented in the PMU are pro-Iranian, of course. But the three core Shiite

groups of Kataeb Hezbollah, the Badr Organization, and Asaib

Ahl al-Haq answer directly to the IRGC.

Iran also enjoys political preeminence in Baghdad. The ruling Islamic

Dawa Party is traditionally pro-Iranian, while the Badr Organization controls

the powerful interior ministry, which has allowed it to blur the boundaries

between the official armed forces and its militias, thus allowing rebranded

militiamen to benefit from U.S. training and equipment. Saudi Arabia,

meanwhile, has been left playing catch up: Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi

visited Riyadh in late October to launch the new Saudi-Iraqi Coordination

Council, the first time an Iraqi premier had made the trip in a

quarter-century. But it is not clear that the Saudis have much more up their

sleeve than financial inducements to potential political allies.

In Yemen, where the Saudis have tried their hand at direct military

intervention, the results have been mixed. The Houthis and their allies,

supported by Iran, have failed to conquer the entirety of the county and have

been kept back from the vital Bab el-Mandeb Strait as

a result of the 2015 Saudi intervention. But Saudi Arabia is bogged down in a

costly war with no end in sight, while the extent of Iranian support to the

Houthis is far more modest.

This, then, is the scorecard of the Saudi-Iranian conflict. So far, the

Iranians have effectively won in Lebanon, are winning in Syria and Iraq, and

are bleeding the Saudis in Yemen.

In each context, Iran has been able to establish proxies that give it

political and military influence in the country. Tehran also has successfully

identified and exploited seams in their enemy’s camp. For example, Tehran acted

swiftly to nullify the results of the Kurdish independence referendum in

September and then to punish the Kurds for proceeding with it. The Iranians

were able to use their long-standing connection to the Talabani family, and the

Talabanis’ rivalry with the Barzanis,

to orchestrate the retreat of Talabani-aligned Peshmerga forces from Kirkuk in

October, thus paving the way for the city and nearby oil reserves to be

captured by its allies.

There is precious little

evidence to suggest that the Saudis have learned from their earlier failures

There is precious little evidence to suggest that the Saudis have

learned from their earlier failures and are now able to roll back Iranian

influence in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia is no better at building up

effective proxies across the Arab world, and has done nothing to enhance its

military power, since Mohammed bin Salman took the reins. So far, the crown

prince’s actions consist of removing the veneer of multiconfessionalism

from the Lebanese government, and threatening their enemies in Yemen.

Those may be important symbolic steps, but they do nothing to provide

Riyadh with the hard power it has always lacked. Rolling back the Iranians,

directly or in alliance with local forces, would almost certainly depend not on

the Saudis or the UAE, but on the involvement of the United States, and in the

Lebanese case, perhaps Israel.

It’s impossible to say the extent to which Washington and Jerusalem are

on board with such an effort. However, the statements last week by Defense

Secretary James Mattis suggesting that the United States intends to stay in

eastern Syria, and by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that Israel will

continue to enforce its security interests in Syria, suggest that these players

may have a role to play.

Past Saudi behavior might encourage skepticism. Nevertheless, the

Iranians here have a clearly visible Achilles’ heel. In all the countries where

the Saudi-Iran rivalry has played out, Tehran has proved to have severe

difficulties in developing lasting alliances outside of Shiite and other

minority communities. Sunnis, and Sunni Arabs in particular, do not trust the

Iranians and do not want to work with them. Elements of the Iraqi Shiite

political class also have no interest of falling under the thumb of Tehran. A

cunning player looking to sponsor proxies and undermine Iranian influence would

find much to work with, it’s just not clear that the Saudis are that player.

Mohammed bin Salman, at least, appears to have signaled his intent to

oppose Iran and its proxies across the Arab world. The game, therefore, is on.

The prospects of success for the Saudis will depend on the willingness of their

allies to engage alongside them, and a steep learning curve in the methods of

political and proxy warfare.

For updates

click homepage here