By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Afghanistan today

One year ago, the

democratic government of Afghanistan collapsed.

The humiliating evacuation of U.S. military forces, civilians, and roughly

100,000 Afghans remain a sore spot for Washington and its allies. The Taliban

regime has ruled the country ever since. Levels of violence throughout the

country have been dramatically reduced—but so, too, have women's rights, the

freedom of the media, and the safety of those who supported the overthrown

democratic government. Questions about the new state of affairs abound. Should

the international community recognize the Taliban? Will the Taliban moderate

themselves? Can diplomacy or sanctions compel them to do so? Is a new

international terrorist threat forming under the Taliban’s watch?

And an even more

pressing question over the country: Is the Afghan civil war that started in

1978 finally over? For four decades, Afghanistan tore itself apart. Mujahideen

fought communists. Warlords fought warlords. The Taliban fought the

Northern Alliance. The democratic republic’s army fought the Taliban. In the

process, more than two million Afghans were killed or wounded, and more than

five million became refugees. Last year’s withdrawal of foreign

forces from the country ended that cycle and allowed the Taliban to consolidate

control—at least for the time being. Pockets of resistance to

Taliban rule, the Taliban’s continued embrace of the tactics of terrorism,

and foreign intervention could all potentially rekindle the civil war in

ways that are not apparent now. Today appears to be a new peace

period, maybe just a pause in Afghanistan’s prolonged trauma. Washington’s

ability to do much about this is limited. The most important thing is to be

cognizant of how previous interventions prevented the civil war from ending.

Getting involved in Afghanistan again to mitigate risks to U.S. national

security would pose an even greater risk: worsening the tragedy for the Afghan

people.

The Soviets regarded Central Asia as their vulnerable southern flank and were

eager to project their power into Afghanistan and the Middle East to protect

the region. The Western powers regarded the whole of Southwest Asia as an

oil-rich zone vital to the West's economy that was within striking distance of

the Soviets.

Far from a monolithic movement, the term “Taliban” encompasses everything from old

hard-liners of the pre-9/11 Afghan regime to small groups that adopt the name

as a ‘flag of convenience. Plus, the Afghan-Pakistani border is an unnatural

political overlay on a fragmented landscape that is virtually impossible for a

central government to control.

The Taliban groups

also were never defeated in 2001, when the United States moved to topple their

government in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. They primarily declined combat in

the face of overwhelmingly superior military force. Though they were not, at

that moment, an insurgent force, their moves were classic guerrilla behavior,

and their quick transition from the seat of power back to such tactics is a

reminder of how well and how painfully schooled Afghans have been in the

insurgent arts over the last several decades.

Afghanistan has

never been entirely peaceful. Tribal feuds, government repression, border

skirmishes, and dynastic plots have been part of Afghan life for centuries. It

is a hard place to govern. Tribal norms place a high value on the individuality

of every member of a tribe, and no government—including the monarchy that ruled

the country from 1747 to 1973—has ever been able to control the country’s

hundreds of tribes, subtribes, and clans. Religious leaders—village mullahs,

Islamic scholars, and judges—also play an essential role in society. They, too,

have posed checks on the power of state authorities and have sometimes called

for jihad against foreign invaders and Afghan rulers.

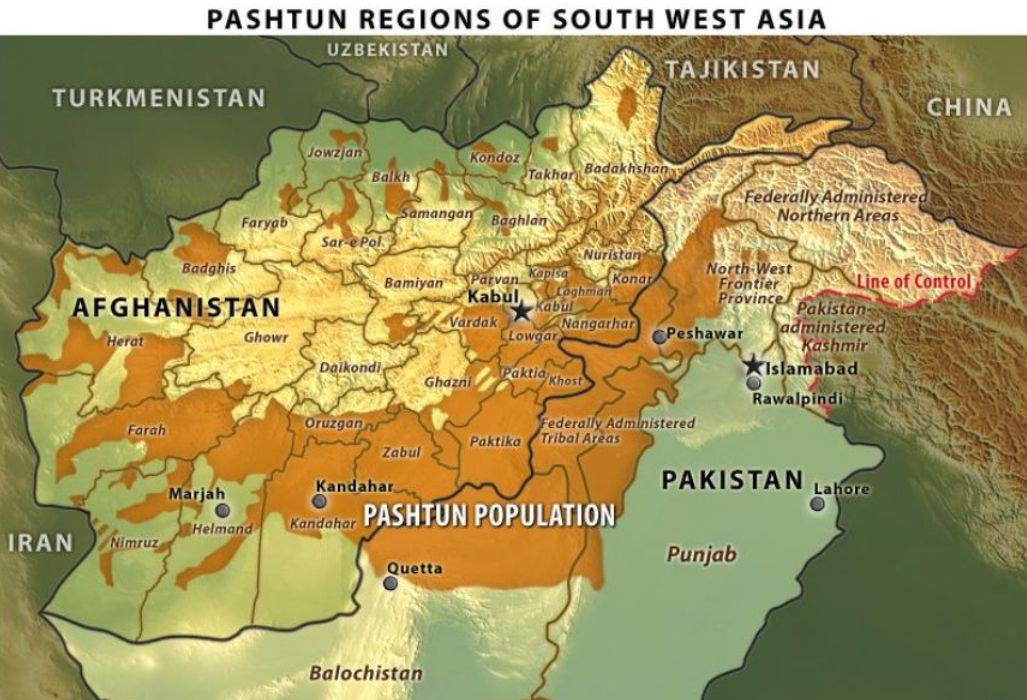

The Durand Line

But there was a kind

of stability to the instability. Tribes were too divided to pose an existential

threat to the country or society. The monarchy’s plotting and short bursts of

violence were too brief to prevent leadership transitions. Attempts by the

monarchy to oppress Afghans were deterred mainly by the tribes and religious

leaders. And nearly a century after the British invasion and occupation of

1878–81, no major foreign invasions upset the equilibrium.

Following a standoff

between the Russian British Armies, Afghanistan's frontier with British India

was drawn by Sir Mortimer Durand in 1893 and was accepted by representatives of

both governments. Recognizing Afghanistan as a buffer between the two empires

saved the Russians and the British from having to confront each other

militarily. The Durand Line, the border, intentionally divided Pashtun tribes

living in the area to prevent them from becoming a nuisance for the Raj. On

their side of the frontier, the British created autonomous tribal agencies

controlled by British political officers with the help of tribal chieftains

whose loyalty was ensured through regular subsidies.

Forces of

modernization began to tip that balance in the late twentieth century. But

the event that sparked 40 years of the civil war was the Saur Revolution in

1978. Communists overthrew the regime of Daoud Khan, the former king's

cousin, and successor. Yet the communists enjoyed only a small base of popular

support, and their education, land, and marriage reforms prompted a backlash

among tribes, religious leaders, and the rural population. In 1979, an

insurgency formed and advanced rapidly. In December of that year, the Soviet

Union invaded Afghanistan to prevent the defeat of the incipient

communist regime.

Stable instability

The Soviet invasion

brought modern industrial war to Afghanistan, leading to a decade of bloodshed.

Most Afghan casualties and refugees from the past 40 years occurred during this

period. Soviet tanks, aircraft, and artillery smashed into villages, which were

militarized in response. Resistance to the occupation united once disparate

tribes, ethnic communities, and religious leaders. Declaring themselves holy

warriors, the people rose, armed with assault rifles, rocket-propelled

grenades, and sophisticated communications gear supplied by the United States,

Saudi Arabia, and other countries.

The Soviet defeat and

departure in 1989 left the mujahideen without a common enemy, especially after

the communist regime finally fell in 1992. They turned to fight each other. War

entered Kabul itself. Many Afghans remember this as the worst part of the past

40 years. The different sides razed neighborhoods and victimized communities. The

tribal and ethnic community leaders that had been mujahideen became warlords.

Taliban rise and fall

The Taliban emerged

out of the chaos of the early 1990s. In his 2010 book, My Life with the

Taliban, Abdul Salam Zaeef, who served as Taliban ambassador to Pakistan

during the 2001 U.S. invasion, argued that “the Taliban were different” than

what had come before. “A group of religious scholars and students with

different backgrounds, they transcended the normal coalitions and factions,”

Zaeef wrote. “They were fighting out of their deep religious belief in jihad

and their faith in God. Allah was their only reason for being there, unlike

many other mujahedeen who fought for money or land.” Although combat persisted

in the north, the Taliban reduced violence in much of the country, slowly

gaining ground such that by 2001 their rivals were reasonably contained. Their

rule appeared stable, if harsh.

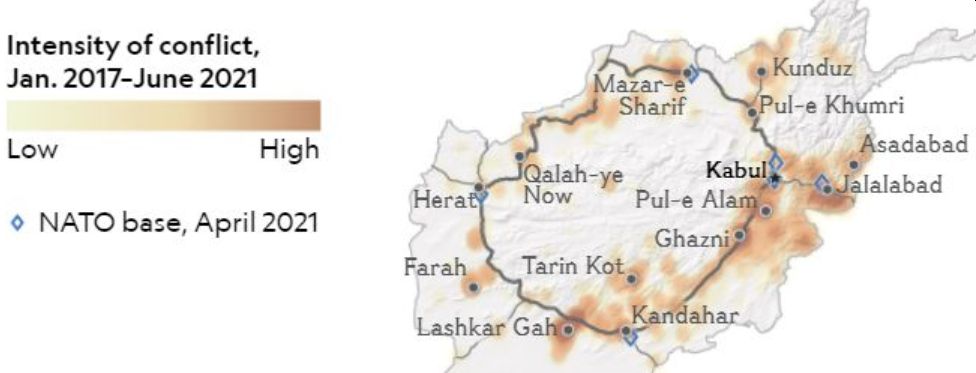

The U.S.-led

intervention in 2001 toppled the Taliban regime and briefly created greater

peace and freedom than Afghans had experienced since at least 1978. In the

years that followed, however, it became clear that the more consequential

effect of the invasion was the rekindling of Afghanistan’s civil war. The

challenges of governing were not going away quickly. Nor were the Taliban.

Taking advantage of mistakes in U.S. policy, misrule by the Kabul government,

and Pakistan's support, the Taliban movement turned into a capable insurgency. Violence and instability persisted until August 2021.

The war between

Western forces and the Taliban changed Afghan society dramatically. The

casualties from bombs, mines, night raids, and drones can most easily be seen.

War also disrupted the economy; many Afghans depended on poppy cultivation for

income. Afghans experienced their first legitimate elections. Parliament had

absolute power for the first time. Yet, in the end, democracy lost out.

Religious extremism

The source of Afghan

political power that has proved most enduring is religion. In

the anarchy following the Soviet withdrawal, the traditional Islam of the

villages retained credibility among the people. As the anthropologist

David Edwards has written, “Islam migrates better than honor or nationality. As

a portable system of belief and practice whose locus is personal faith and

worship, it can be adapted to a variety of contexts and situations but

estranged from the familiar settings in which it arose, is it not also more

resistant to the mundane negotiations and compromises that everyday life

requires?” Through the Taliban, a religious movement ruled Afghanistan for the

first time in the modern era. That was no flash in the pan. The sign survived

20 years of war and rules again, making the Taliban the most significant

religious force in Afghanistan’s modern history.

The civil war and its

foreign interventions have a yet darker side. They bred extremism. As Edwards

charts in his 2017 book, Caravan of Martyrs, the Soviet invasion

and the U.S. and Pakistani support for the mujahideen pushed martyrdom to the

forefront. Foreigners—the Palestinian Abdullah Azzam

and the Saudi Osama bin Laden foremost—brought with

them ideas of terrorism and suicide bombing. Throughout the U.S. intervention,

the Taliban could not divorce themselves from either. Siding against foreign

terrorism risked criticism from internal supporters, and suicide bombing was an

invaluable weapon against U.S. and government forces.

Radical ideology was

the catalyst. While studying at King Abdul Aziz University in Jeddah, Saudi

Arabia, in the late 1970s, Osama bin Laden

joined the Muslim Brotherhood, a radical Islamic group founded in Egypt in

1928. Osama bin Laden.

As the leader of the

Taliban from 2016 onward, Mawlawi Haibatullah

has endorsed the use of terrorism. In 2008, Haibatullah

advised the Taliban founder and leader Mullah Omar that Islam justified a wider

use of suicide bombings. Haibatullah’s 23-year-old

adopted son blew himself up in a car bomb during an attack in Helmand in 2017,

recording a video before setting off on the mission. Until then, no other

Afghan leader had ever martyred a son, adopted or otherwise, signifying how

values were changing. Traditionally, sons were to be cherished, not cast aside

needlessly. An embrace of martyrdom and an indifference to the lives

of civilians had become part of what it meant to belong to the Taliban. One can

only hope that the trend fades with the departure of foreign powers and becomes

an aberration in Afghan history.

Where to go from here?

A year after the U.S.

withdrawal, it remains uncertain whether a new form of stability has taken hold

in Afghanistan. The war may have genuinely been a transformational process for

Afghan society. It is possible that the Taliban’s Islamic government may be

able to keep violence at bay, enjoy a base level of legitimacy among the

people, and deter foreign intervention. It is also possible, however, that the

civil war is not yet over. It paused for parts of the country during the

Taliban rule in the 1990s and during the first years of the U.S. intervention

from 2001 to 2005. With that historical precedent in mind, a new unstable

balance may not be apparent for another five years.

Peering ahead, a

renewed civil war could take many forms. One is the resumption of decades-long

fighting between the Taliban, composed primarily of Pashtuns and resistance

groups based in the country’s north that tend to draw from Afghanistan’s

Hazara, Tajik, and Uzbek minorities. So far, the Taliban has faced little more

than sporadic attacks from these groups and fiery statements from their exiled

leaders—a far cry from an effective insurgency. But that could change with time

if the groups can build their cohesion and resilience and win over popular

support. Resistance groups could also receive support from Iran or Russia,

which might decide to aid them because of historical relationships, cultural

ties, opposition to the Islamic State, and competition with Pakistan.

In a different

scenario, a conglomeration of Afghans in cities around the country could rise.

With sufficiently poor governance, even certain Pashtun tribes could revolt.

Land disputes could also challenge the Taliban. Tribal and villager

dissatisfaction with access to land and water have traditionally caused strife.

The Taliban received support for 25 years from poor farmers to whom they gave

or promised land. For the Taliban to make good on those promises, other

Afghans, including landed tribes with title, must lose land, and they may

resist. How well the Taliban can balance these competing demands matters. So

far, the regime has not been too oppressive, taking a little from the land

without taking it all. Yet land issues can fester and are notoriously difficult

for any government to manage.

The Taliban could

also fuel their undoing. The tactics of terrorism feed violence, and the

Taliban may be unable to control extremist trends. Young men could continue to

look to martyrdom for meaning, grow restive, and look for new targets. Those

targets are as likely to be within Afghanistan as abroad. In late 2021, there

were rumors that Mawlawi Haibatullah

and Sirajuddin Haqqani, deputy leaders of the Taliban government, had declared

an end to suicide bombings. But the presence of the al Qaeda leader Ayman

al-Zawahiri in Kabul, where he was killed in a U.S. drone strike in July, bodes

poorly. A wider acceptance of extremism could create more recruits for the

Islamic State, which maintains a faction in the country and could adapt its

terrorist campaign into an anti-Taliban insurgency.

Perhaps nothing is

more likely to revive the civil war than foreign interventions. Russian and

Iranian efforts to support ethnic and sectarian proxies in Afghanistan and

ill-judged Pakistani moves to tame the Taliban, protect Islamabad’s perceived

interests, or more clearly define an Afghan-Pakistan border could stoke new

violence. U.S. military actions to counter terrorism could also do the same.

Precision strikes on Afghan soil could trigger a backlash among Afghans and

increase support for terrorist groups. Over-the-horizon strikes may be

essential to U.S. national security, but they will likely encourage radicalization

in Afghanistan. Worst of all, in today’s environment of great-power

competition, intervention or influence by one great power could compel others

to intervene, backing their proxies or the Taliban government and producing an

escalatory spiral of violence. That would be a recipe for renewed civil war and

a tragedy for the Afghan people.

The lack of U.S. role

The United States and

its allies may want to be more than passive observers and try to do something

to stabilize the country. There is little harm in providing humanitarian

assistance or stepping aside if other countries want to assist the

Taliban regime. In contrast to supporting the anti-Taliban resistance and

conducting counterterrorism activities inside Afghanistan, such activities

would not raise the risk of restarting the Afghan civil war. But the amount the

United States and its allies can do is limited. The Taliban regime is unlikely

to heed incentives or sanctions to modify its behavior.

Moreover, substantial

U.S. financial assistance to the Taliban regime would likely draw reactions

from China, Iran, and Russia, which would back Afghans to oppose any U.S.

influence. The same is even more true if the United States attempts to support

proxies to supplant the Taliban regime. The best policy for Washington may be

to monitor the situation closely rather than inadvertently cause harm by trying

to help one side or another.

For updates click hompage here