By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

How to engage with the Taliban

Earlier, we argued

that the Taliban regime is unlikely to heed incentives

or sanctions to modify its behavior. One year ago, the democratic government of Afghanistan collapsed. The humiliating evacuation of U.S. military forces,

civilians, and roughly 100,000 Afghans remain a sore spot for Washington and

its allies.

It is clear that

since then, the extremist group has changed little since it first seized

control of the country in 1996. In March 2022, the Taliban decided not to

reopen girls’ secondary schools throughout the country—as it had vowed to do

just two days earlier—putting an end to any hopes that the group would rule the

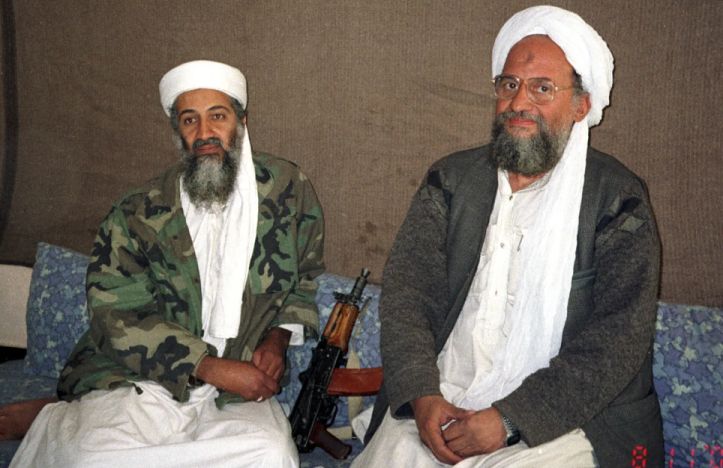

country differently this time around. And, in the weeks since a CIA drone

strike killed al Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahiri in a leafy Kabul enclave, it has

become even more apparent that the Taliban continues to harbor terrorist

groups.

It is time for the

United States and its partners to acknowledge these facts and adopt an approach

to the Taliban that appropriately addresses their actions instead of

encouraging them to continue making empty promises and offering excuses for

their outrageous behavior. Getting more rigid with the Taliban would not mean

interfering with humanitarian assistance to the Afghan people. It would mean

working closely with the United Nations and like-minded countries to impose

consequences on the Taliban for their unacceptable behavior and withholding

high-level engagement with the group until its leadership pursues more moderate

policies.

No change in behavior

Before the

U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan last year, many observers hoped that

the Taliban’s desire for international assistance and legitimacy would help

moderate their behavior once they were in power. On August 17, 2021, just two

days after the Taliban seized Kabul and took control of Afghanistan’s

government, longtime Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid addressed journalists

gathered for the Taliban’s first official news conference, assuring them that

Afghanistan’s new Taliban-led government would allow women to work, study, and

otherwise participate in society “within the bounds of Islamic law.”

In today’s

Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, women and girls over 12 are officially

prohibited from attending school and have few options for earning wages or

working outside the home. They face strict dress code requirements, new

restrictions on leaving their homes without a close male relative, and

increasing rates of child marriage and domestic abuse.

The Taliban has

disbanded the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, banned political

activities, and arrested and interrogated the leaders of civil society

organizations. They have systematically silenced human rights activists,

women’s advocates, and others working to build an open and inclusive Afghan

civil society. In February, the Taliban arrested more than 20 women activists

daily.

In May, UN Special

Rapporteur on Afghanistan Richard Bennett warned that the Taliban are creating

a society ruled by fear. The Taliban’s disregard for basic human rights has

proved deadly for many Afghans who worked in the previous government or its

national security forces. Since last August, the UN Assistance Mission in

Afghanistan has documented over 237 extrajudicial killings carried out by

members of the Taliban. The victims have included 160 members of the former

Afghan government and security forces. During the same period, new restrictions

on media have constrained journalists’ ability to report freely and forced at

least one-third of Afghan news outlets to shut down—which means that the number

of killings is likely far higher.

Some courageous

Afghan activists are fighting back. PenPath, an

Afghan organization working to reopen schools, continues campaigning for girls’

education in some of the most remote parts of the country. Female civil

servants with the Advocacy for Change Movement continue to call on the

Taliban-led government to respect women’s rights. These organizations, and

others like them, deserve international attention and support.

As part of the 2020

Doha agreement that the Taliban made with the United States, the group pledged

to prevent al Qaeda from using Afghan soil to threaten the security of the

United States and its allies. But any illusion that the Taliban intended to

make good on that promise was shattered in late July when it became clear that

Zawahiri, the al Qaeda leader, had been

living in a Kabul neighborhood at the home of an acting associate Interior

Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani.

To some extent,

eliminating Zawahiri vindicates U.S. President Joe Biden’s argument that “over

the horizon” operations are an effective way to deal with terrorist threats.

But it also demonstrates that the Taliban retains close links with al Qaeda and

that the terrorist group is taking advantage of the Taliban’s return to power

to rebuild its base in Afghanistan. U.S. Secretary of State has said that

the Taliban’s sheltering of Zawahiri (who earlier operated suicide bombers) breached

the Doha agreement. But the vaguely worded deal, which the Trump administration

negotiated, does not explicitly require the Taliban to expel al Qaeda and other

terrorist organizations from Afghan territory.

Engagement has proved futile

Some security experts

argue that if the United States does not continue high-level engagement with

the Taliban, Afghanistan will likely descend into civil war and chaos

and become an even bigger headache for the West than it already is. Others

argue that the immediate need to work with the Taliban regime to ensure that

humanitarian assistance reaches desperate Afghans should take precedence over

human rights concerns. Both arguments miss the mark.

Agreeing to engage

with the Taliban regardless of their human rights record will not

encourage stability over the long run. How the Taliban governs its people is a

better determinant of the country’s political stability than whether the United

States or any other country sits down for talks with the Taliban. Suppose the

Taliban regime continues its repressive approach. In that case, the Afghan

people will increasingly resist violations of their rights and freedoms. They

may even gravitate toward further violent resistance—regardless of whether U.S.

officials are talking to the regime. Pattana Durrani, the executive director of the Afghan education

nonprofit LEARN, recently told an interviewer that “the most important thing I

would want the international community to understand is the fact that meeting

Taliban doesn’t help.”

In late August, the

UN warned that 24 million Afghans still require humanitarian relief and that

more than $700 million is needed to help Afghans get through the

coming winter. But Washington should limit its engagement with the Taliban to

agreeing on a set of principles for delivering aid, including Taliban

noninterference in the work of the organizations carrying out aid programs.

There is a growing concern that Taliban leaders are trying to manipulate

humanitarian assistance by selecting which communities receive it and directing

aid organizations to recruit workers from lists they provide.

On September 14, the

Biden administration announced that $3.5 billion in frozen Afghan assets would

not be released to Afghanistan’s Taliban-controlled central bank. On September

14, the Biden administration announced that the money would be

distributed to the Afghan people through an international fund managed by Swiss

government officials and experts. The new Afghan Fund will disburse that $3.5

billion to benefit the Afghan people.

But the most

significant step the United States can take to show the Taliban that it won’t

be business as usual is to back the reinstatement of the UN travel ban for all

Taliban leaders, which had been waived since 2019. The waiver expired in late

August when the UN Security Council disagreed on whether to extend it. Still,

Russia and China will likely seek more travel exemptions for the Taliban. If

the international community continues to allow Taliban officials to travel

abroad, it will send the signal that it is acceptable for them to continue

repressing women and girls. In the past year, the Taliban used the waiver on

the travel ban to try to establish international legitimacy by attending

international conferences in Norway in January and Uzbekistan in July. Back

home, the regime violated women’s rights and intensified its crackdown on

Afghan civil society.

As Washington reduces

its diplomatic engagement with the Taliban, it should also focus on finding

creative ways to support Afghan civil society, such as providing resources to

local Afghan groups that monitor human rights abuses and promote women’s rights

and media freedoms, and inviting them to speak at international gatherings.

Washington could also allocate more resources to the UN Assistance Mission to

Afghanistan to enhance its focus on preventing human rights abuses and working

more closely with Afghan civil society. It is also essential that the

international community maintain its informal consensus against recognizing the

Taliban as Afghanistan’s legitimate government until the group meets basic

governance and human rights standards and takes steps to break ties with

terrorists.

Over five months

since the Taliban broke their promise to reopen girls’ secondary schools. After

spending hundreds of millions of dollars over the past 20 years supporting

organizations that promote women’s rights in Afghanistan, the United States has

a moral obligation to Afghan women and girls. The very women and girls that

Washington helped empower are now losing their rights to education and

employment, and many now fear for their lives. The UN and international human

rights organizations have documented numerous human rights cases of abuse

against women and girls, including extrajudicial killings, arbitrary detentions,

forced displacement, persecution of minorities, torture, and a clampdown on

journalists and freedom of expression over the last year. The Taliban’s actions

are unacceptable, and U.S. policy must reflect this by adopting a stricter

approach to the Taliban until the group upholds its previous promises to

respect the rights of all Afghans.

For updates click hompage here