By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Africa and the war in Ukraine

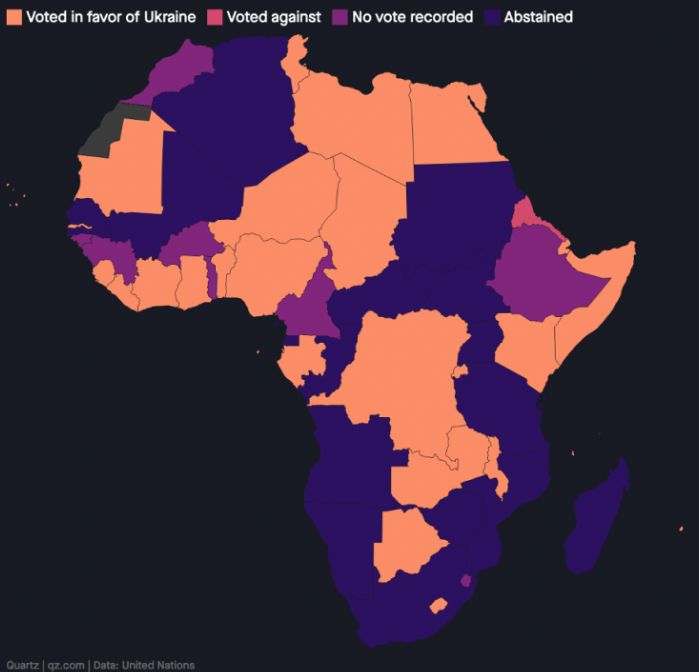

As Russian President

Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine enters its seventh month, many African

countries have yet to show strong support for Kyiv, to the chagrin of Western

leaders. In the early days of the conflict, after 17

African countries declined to back a UN resolution condemning Russia,

several European diplomats assigned to African capitals made a great show of

browbeating African leaders for not taking a stand against the invasion. South

African President Cyril Ramaphosa, in particular, was

the target of some strikingly undiplomatic tweets, with Riina Kionka, at the time the EU’s ambassador to Pretoria, writing

that “we were puzzled because [South Africa] sees itself and is seen by the

world as a country championing human rights.”

Stephen Chan, a

professor of world politics at the University of London’s School of Oriental

and African Studies (SOAS), said the visits by Macron and Lavrov demonstrated

the increased need to woo Africa at a time of growing global tension and a

potential “new

Cold War.”

Despite continued

Western pressure, the

situation has not changed much in the months since. In July, for example,

French President Emmanuel Macron traveled to central Africa and West Africa to

rally support for Ukraine. Yet, he managed only to rankle many African leaders

when he accused them of “hypocrisy” for refusing to condemn the war. By

contrast, during a visit to multiple African countries that same month, Russian

Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov emphasized Russia’s ties with the continent and

portrayed Russia as a “victim” in Ukraine. Only a handful of

African countries—Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria among them—have taken a strong stance

on the war, and even these have focused primarily on denouncing aggression more

broadly and on general calls for diplomacy and peace rather than on specific

criticism of Moscow.

Although leaders

in the West are puzzled by these developments, there are clear reasons for

African countries’ reluctance to embrace the Western narrative about Ukraine.

For one thing, Africa is a vast, complicated, and highly diverse continent. Its

54 countries and territories each have unique circumstances and histories and

different relations with Russia and the West. It would be unreasonable—and

condescending—to assume that the continent’s leaders could unify around a

single position instantaneously. When African countries have come together

around a common position in the past, it has often been after years of

deliberation, as with the transition from the Organization of African Unity to

the African Union, which took place in 2002 but had been in the works since the

late 1990s. On other occasions, a common front has been driven by a specific

and urgent threat, such as the Mano River Ebola outbreak or the COVID-19

pandemic. African countries knew they could not weather without a united front.

For Africa, Russia’s war in Ukraine has neither of these qualities.

Moreover, the skepticism

in African capitals about taking the Western side in a faraway war in Europe is

also rooted in a power imbalance between the West and African countries that

routinely plays out as structural violence. Beyond many historical injustices

that are not acknowledged—let alone accounted for—contemporary forms of

injustice persist. Leaders of Western nations are quick to sweep violent

colonial and neocolonial histories under the rug while African countries

continue to deal with their consequences. Consider the COVID-19 pandemic, in

which African countries were left begging for medicines and vaccines that

Western nations were throwing away by the millions, compounding the sense of

conditional friendship. Once Russia’s efforts to sway African countries are added

to the mix, history makes it difficult for the United States and its European

allies to build an African coalition against Moscow.

Putin and the freedom fighters

Of course, Russia’s

activities in Africa explain African reluctance to fall into line with the West

on Ukraine. As Western governments and analysts have noted, Moscow has been

engaged in a large-scale disinformation campaign to shape African opinion about

the conflict, particularly online. This effort builds on previous Russian

disinformation campaigns that have affected political processes elsewhere,

including in the United States. In May, The Economist published

a study of Twitter accounts used to spread Russian disinformation about the

war; many of these were based in Africa and seemed to be deliberately targeting

African communities.

One doctored image

shared widely by African Twitter accounts since the war began purportedly

showed a young Putin with former President of Mozambique Samora

Machel in a Tanzanian training camp for freedom fighters in the 1970s. In

reality, no such meetings could have occurred: Putin is not old enough to have

been in Tanzania when these photographs were taken. But the images went viral,

partly because they reinforced African grievances about the West’s colonial

legacy on the continent. Indeed, Machel later died in a mysterious plane crash

that South Africa’s Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission linked to the

apartheid government in South Africa, at the time a Western ally.

The wars of

decolonization in Africa are not ancient history. As recently as 2018, a group

of living victims of the British colonial government in Kenya successfully sued

the British government for the torture they endured in internment camps during

Kenya’s independence war in the 1950s. Other Cold War injustices are only

beginning to be addressed. In June of this year, the Belgian government

returned to the victim’s descendants a gold-crowned tooth that belonged to

Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo

(DRC), who was assassinated by a Belgian execution squad in 1961 in a

U.S.-backed plot.

For many countries,

communism provided an alternative to Western colonialism and a basis for

twentieth-century African independence movements. This legacy has allowed

contemporary Russia, a successor state to the Soviet Union, to portray itself

as on the right side of African history. Of course, Soviet support for

decolonization movements did not come only from Russia: much of it came from

other parts of the communist bloc, including Ukraine. But Russia has acquired

this reputation and exploited Africa’s complicated relationship with the West.

Better armed than allied

A second reason

African countries have been slow to support Ukraine stems from differences in

how African countries and their Western counterparts view contemporary

geopolitics. Many governments currently pivoting to Russia—including Mali,

Ethiopia, and Uganda —owe their political survival to Russian support. For

instance, Russia is a key weapons supplier and has provided military support

through mercenary forces like the Wagner Group to many African countries that

abstained from the UN vote condemning Russian aggression. Today, according to

the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Russia is Africa's most

powerful weapons exporter, accounting for 44 percent of weapons purchases

between 2017 and 2021. (Ukraine is also a weapons supplier to some African

countries, particularly South Sudan.)

Several African

leaders with longtime Western backing have not hesitated to cultivate Russian

military support. With Western support, for example, Yoweri Museveni has ruled

Uganda for 38 years; Paul Biya has ruled Cameroon for

40. Both have remained in office despite copious evidence of crimes against

their people. (Macron was in Cameroon when he made his remark about hypocrisy.)

Yet, although the United States trains Ugandan soldiers to fight on its behalf

in countries like Somalia, Uganda primarily buys its arms from Russia and has

the sharpest increase in military expenditure in Africa in 2020. Similarly,

Cameroon, a significant beneficiary of French largesse, signed a weapons deal

with Moscow in April 2022, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For

authoritarian regimes, efforts to play off both sides’ ties have reinforced the

continent’s ambivalence toward Ukraine.

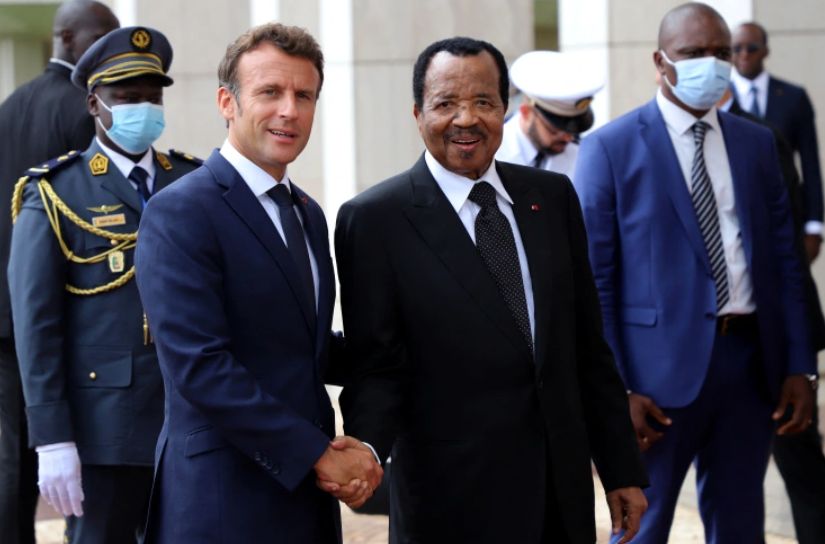

Cameroon's President

Paul Biya (right) with his French counterpart

Emmanuel Macron at the presidencial palace in Yaounde, Cameroon:

But for other

countries, what Macron calls hypocrisy is more plausibly understood as conflict

fatigue. After all, Africa has experienced and continues to experience

many intractable wars. During the Cold War, many African wars were proxy

battles between the Soviet Union and the United States. Although Western powers

have been slow to recognize it, the legacy of those conflicts—including in

Angola, the DRC, Mozambique, and elsewhere—continues to cast a long shadow on

many parts of the continent. The last time Africans were asked to take sides in

a war between the West and East, countries were devastated, and millions of

people died.

In his classic essay

on decolonization, “Concerning Violence,” published in his 1961 book The

Wretched of the Earth, the psychiatrist and political philosopher Frantz

Fanon wrote that “neutralism produces in the citizen of the third world … a

fearlessness and an ancestral pride resembling defiance.” He argued that for

African countries, staying neutral was necessary for survival. But he

criticized African leaders for allowing neutralism to fuel foreign efforts to

militarize the continent. Today, the same pattern is emerging, and the warning

stands. Russia has promised to expand weapons supplies to African countries to

buy their allegiances. Now, many activists and leaders in pro-democracy circles

fear that the continent is entering another period in which efforts by foreign

powers to buy friends in African governments will herald a new era of poor

leadership.

The missing peace

African countries

have a unique vantage

point toward Russia’s war in Ukraine. Rather than inviting more of them to

join in the war, Western countries could use this opportunity to allow Africans

to practice the lessons they have learned from generations of war on their

soil. The African Union has declared that one of its aims is “silencing the

guns by 2030,” African countries have some of the most complex mechanisms for

peace and security in the world, partly because they are so frequently called

into use. For example, the Peace and Security Council of the African Union is a

standing decision-making body within the union. At the same time, subregional

organizations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

have gone as far as building their peacekeeping and early warning capacities.

For those who have worked with such bodies, the overarching question about the

war in Ukraine is, “Where are the peacemakers?” Aside from the UN

Secretary-General, they do not see much evidence of world leaders urging

de-escalation. Isn’t a conflict between Russia and the West the precise

scenario that international diplomacy exists to address?

Thousands of people have been killed in the conflict

in Tigray:

Indeed, African

countries know how difficult ending wars can be. In East Africa, multiple

conflicts are underway, including in eastern DRC, Ethiopia, Somalia, South

Sudan, and Sudan. Several of these have been devastating: there is mounting

evidence of genocide

in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, and Sudanese people continue to struggle for

an end to military rule as other countries—including Russia—offer the military

regime military and financial support. These conflicts have triggered interventions

by the African Union, the Inter-Governmental Agency for Development, and the

East African Community, not to mention a few bilateral efforts at mediation.

Some of these wars have been raging for a generation. African countries’

collective hesitation to be drawn into Ukraine must be interpreted, in part, in

light of this visceral awareness of the long-term harm that wars on the

continent have produced.

History reminds

African countries to approach Ukraine’s conflict cautiously and treat

claims of friendship with suspicion. For many Africans, the current

overtures from Russia and the West are not about friendship. They are about

using Africa as a means to an end. Authoritarian leaders like Biya can and have reaped benefits from the war. But the dominant

African position, given the significant uncertainties about the war and its

outcome, has been to demand peace and urge diplomacy—and, whenever possible, to

avoid having to take sides in a conflict that seems unlikely to offer much to

Africa, mainly if it turns the continent into a new theater of proxy war.

For updates click hompage here