By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Operation Al-Aqsa Flood

Operation Al-Aqsa Flood

and Operation Swords of Iron are military operations that began on 7 October

2023 when rockets were fired by Palestinian militants at Israel from the Gaza

Strip, with the latter being the Israeli counter-operation. This was

accompanied by militant infiltrations into kibbutzim surrounding Gaza and the

Israeli city of Sderot, which included the taking of hostages. Palestinian

media reported the kidnapping of Israeli families and elderly people to Gaza.

In response, Israel

launched raids on the Gaza Strip. Defense Minister Yoav

Gallant approved the

call-up of reserve forces.

Hamas leader Saleh

al-Arouri stated that the

"Mujahideen"

had begun an operation to defend Al-Aqsa

Mosque and liberate

the prisoners. Al-Qassam Brigades published

pictures of captured Israeli soldiers. Navigation traffic was disrupted at

airports in central and south Israel.

The operation began

with a surprise attack, which

Hamas states is in response to Israel's "desecration

of Al-Aqsa". And

occurred only a day after the 50th anniversary of the Yom

Kippur War, which

also began with a surprise attack. It is also the culmination of a massive wave

of violence in Israel throughout the High

Holy Days.The

attack began at 06:34 in the morning with a widespread launch of Palestinian rockets towards

Israel, from Dimona in the south to Hod HaSharon in the north and Jerusalem in the east. Hits were observed in many places,

and some resulted in casualties, especially in the Bedouin communities.

With the rocket fire,

dozens of Palestinian militants infiltrated communities in the Gaza

envelope, including

through drones and breaches in the IDF fence, riding on motorcycles and ATVs. The IDF was caught entirely off guard by the attack.

The Palestinian militants infiltrated Israeli towns as Sderot, Ofakim, and Netivot, killed several unarmed civilians, and took hostages

in kibbutzim near the border. According to Israel's Police

Commissioner, Kobi Shabtai, there

are still 21 active hotspots in the southern region.

Defense

Minister Yoav Gallant approved

a wide-scale call-up of reserves and declared a special state in a radius of up

to 80 kilometers from the Gaza Strip border. About an hour after the attack

began, the IDF spokesperson instructed residents of the south and central

regions to stay close to protected areas and within the Gaza envelope in a

protected space. About two hours after the attack began, the IDF began its

offensive in the Gaza Strip.

Mohammed Deif, the head of Hamas' military wing, presented the

reason for the attack as the "Jewish ascent to the Temple

Mount" during

the Sukkot holiday and called on the residents of the Gaza

Strip and Arab Israelis to join the attack, which he referred to as

"Operation al-Aqsa".

In the Palestinian

media, it was reported that bodies of Israeli soldiers were captured in the

territory of the Gaza Strip, as well as Israeli military vehicles as "war

booty." Israeli authorities did not confirm these reports.

Militants arrived at

a nature party (outdoor rave) in the Re'im Forest, fired

shots at participants, and threw grenades. They also arrived at the Priaon and fired many shots.

Background History

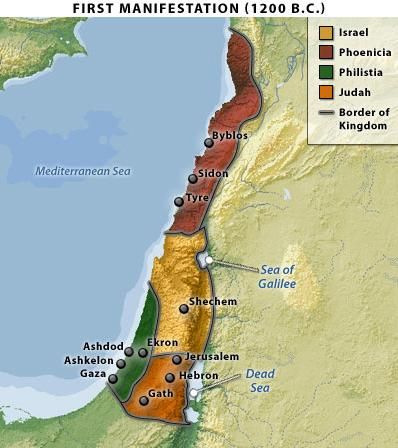

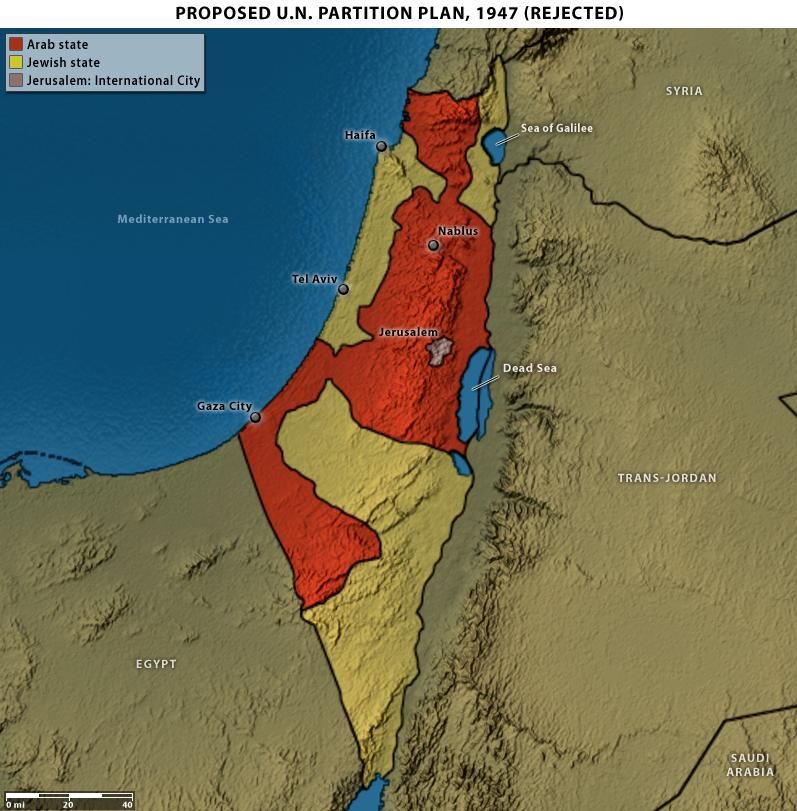

From a historical

point of view, one could say that 'Israel' has manifested itself three

times in history. The first manifestation began with the invasion led by

Joshua. It lasted through its division into two kingdoms, the Babylonian

conquest of the Kingdom of Judah and the deportation to Babylon early in the

sixth century B.C. The second manifestation began when Israel was recreated in

540 B.C. by the Persians, who had defeated the Babylonians. The nature of this

second manifestation changed in the fourth century B.C. when Greece overran the

Persian Empire and Israel and again in the first century B.C. when the Romans

conquered the region.

The second

manifestation saw Israel as a minor actor within the framework of more

considerable imperial powers. This situation lasted until the Romans destroyed

the Jewish vassal state.

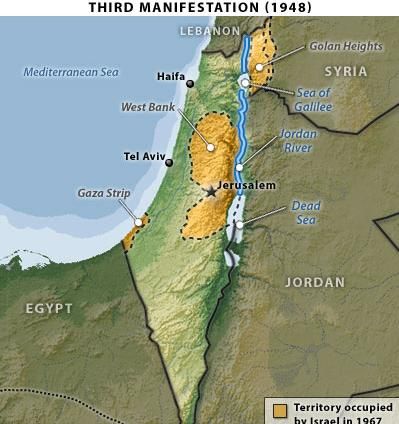

Israel’s third

manifestation began in 1948, following (as in the other cases) an ingathering

of at least some Jews who had been dispersed after conquests. Israel’s founding

takes place in the context of the decline and fall of the British Empire and

must, at least in part, be understood as part of British imperial history.

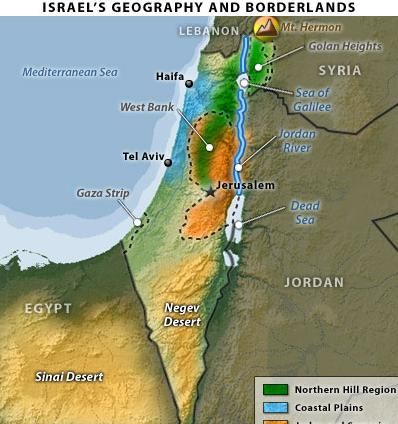

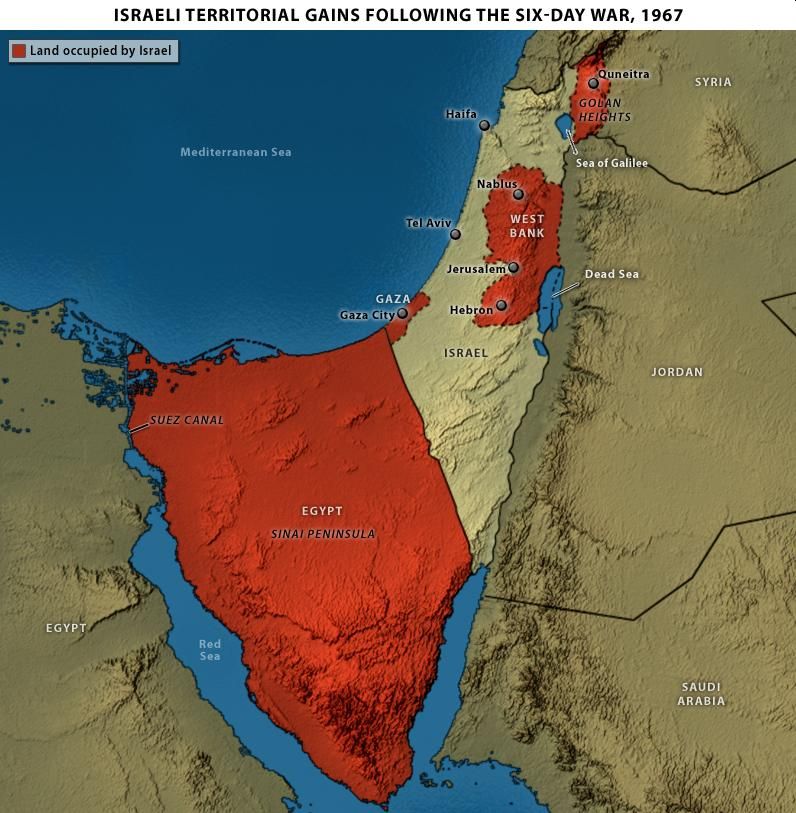

Israel’s reality

today is this. It is a small country, yet it must manage threats far outside

its region. It can survive only if it maneuvers with great powers commanding

more significant resources. Israel cannot match the resources, so it must

constantly be clever. There are periods when it is relatively safe because of

great power alignments, but its normal condition is one of global unease.

On the other hand,

the Arabs don’t care about the Palestinians other than for the destruction of

Israel. For example, Gaza is a nightmare into which the Egyptians forced

Palestinians (fleeing Israel).

The idea for

what were de facto Arab-Muslims to call themselves 'Palestinians' came as

a reaction to the Jewish migration to what is now Israel after

WWI. When World War I ended, the rule of the Ottoman Empire, which

controlled the Middle East, ended.

Shortly after the British took over in 1920, they

moved the Hashemites to an area in the northern part of the peninsula, on the

eastern bank of the Jordan River. Centered around Amman, they named this

protectorate carved from Syria “Trans-Jordan,” as in “the other side of the

Jordan River,” since it lacked any other obvious identity. After the British

withdrew in 1948, Trans-Jordan became contemporary Jordan. The Hashemites also

had been given another kingdom, Iraq, in 1921, which they lost to a coup by

Nasserist military officers in 1958.

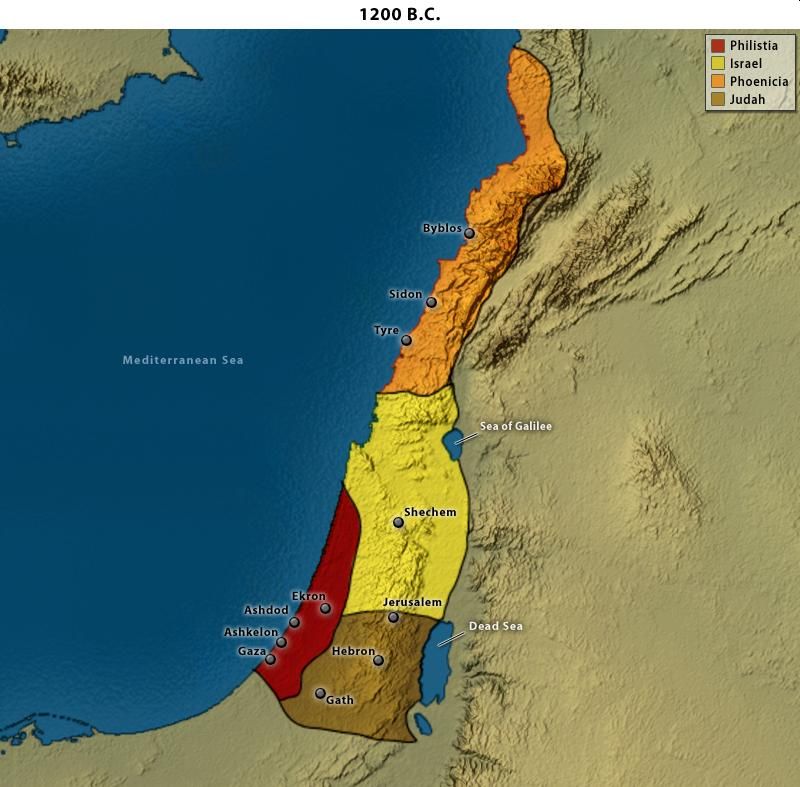

West of the Jordan

River and south of Mount Hermon was a region that had been an administrative

district of Syria under the Ottomans. It had been called “Philistia” mostly,

undoubtedly, after the Philistines whose Goliath had fought David thousands of

years before. Names here have a history. The term Philistine eventually

came to be known as Palestine, a name derived from ancient Greek, which

is what the British named the region.

The French region was further subdivided.

The French had been allied with the Maronite Christians during a civil war that

raged in the region in the 1860s. Paris owed them a debt, so it turned the

predominantly Maronite region of Syria into a separate state, naming it Lebanon

after the dominant topographical characteristic of the area, Mount Lebanon. As

a state, Lebanon had no prior reality, nor even a unified ethno-sectarian

identity; its main unifying feature was that demographically, it was dominated

by French allies.

The British region

was also divided. The Hashemites, who ruled the western Hejaz region of the

Arabian Peninsula, had supported the British, rising against the Ottomans.

In return, the

British had promised to make them

rulers of some sort of Arabian Empire after the war. But in addition to the

Hashemites, London was also allied with the French and with other tribes

against the Ottomans and thus could not make the Hashemites the unquestioned

rulers of all of Arabia (the Peninsula as well as the Levant). Furthermore,

the Sauds in 1900 had launched the

reconquest of Arabia from Kuwait and had gained control over the eastern and

central parts of the peninsula. By the mid-1920s, the Hashemites lost control

over the arm to the Sauds, paving the way for

the eventual creation of Saudi Arabia.

But by then, the

British had moved the Hashemites to an area in the northern part of the

peninsula, on the eastern bank of the Jordan River. Centered around Amman, they

named this protectorate carved from Syria “Trans-Jordan,” as in “the other side

of the Jordan River,” since it lacked any other apparent identity. After the

British withdrew in 1948, Trans-Jordan became contemporary Jordan. The

Hashemites also had been given another kingdom, Iraq, in 1921, which they lost to

a coup by Nasserist military officers in 1958.

West of the Jordan

River and south of Mount Hermon was a region that had been an administrative

district of Syria under the Ottomans. It had been called “Philistia” mostly,

undoubtedly, after the Philistines whose Goliath had fought David thousands of

years before. Names here have a history. The

term Philistine eventually came to be known as Palestine, a name

derived from ancient Greek — and that is what the British named the region,

whose capital was Jerusalem.

Significantly, while

the people of this area were referred to as Palestinians, a demand for a

Palestinian state was virtually nonexistent in 1918. The European concept of

national identity at this time was still very new to the Arab region of the

Ottoman Empire. There were clear distinctions in the region, however. Arabs

were not Turks. Muslims were not Christians, nor were they Jews. Within the

Arab world, there were religious, tribal, and regional conflicts. For example,

tensions existed between the Hashemites from the Arabian Peninsula and the

Arabs settled in Trans-Jordan. Still, these were not defined as tensions

between Jordan and Palestine. They were ancient and genuine but were not

thought of in national terms.

European Jews had

been moving into this region under Ottoman rule since the 1880s, joining

relatively small Jewish communities that had existed there (and in most other

Arab regions) for centuries. The movement was part of the Zionist movement,

which, motivated by European definitions of nationalism, sought to create a

Jewish state in the region. The Jews came in small numbers, settling on land

purchased for them by funds raised by Jews in Europe. Usually, this land was

bought from absentee landlords in Cairo and elsewhere who had gained ownership

of the land under the Ottomans. The landlords sold the land out from under the

feet of Arab tenants, dispossessing them. From the Jewish point of view, this

was a legitimate acquisition of land. From the tenants’ point of view, this was

a direct assault on their livelihood and eviction from land their families had

farmed for generations. And so it began first as real estate transactions,

winding up as partition, dispossession, and conflict after World War II and the

massive influx of Jews after the Holocaust.

As other Arab regions became nation-states in the

European sense of the word, their views of the region developed. Those who

adopted the Syrian identity, for example, saw Palestine as an integral part of

Syria, much as they saw Lebanon and Jordan. They saw the Sykes-Picot agreement as a violation of Syrian

territorial integrity. They opposed the existence of an independent Jewish

state for the same reason they opposed Lebanese or Jordanian independence.

Elements of Pan-Arab nationalism and Islamic identity informed this Syrian view

but were not the key factors behind it. Instead, the critical factor was the

view that Palestine was a province of the sovereign entity known as Syria, and

those we call Palestinians today were simply Syrians. The Syrians have always

been uncomfortable with Palestinian statehood, though not with the destruction

of Israel, and invaded Lebanon in the 1970s to destroy the Palestine Liberation

Organization (PLO) and Fatah.

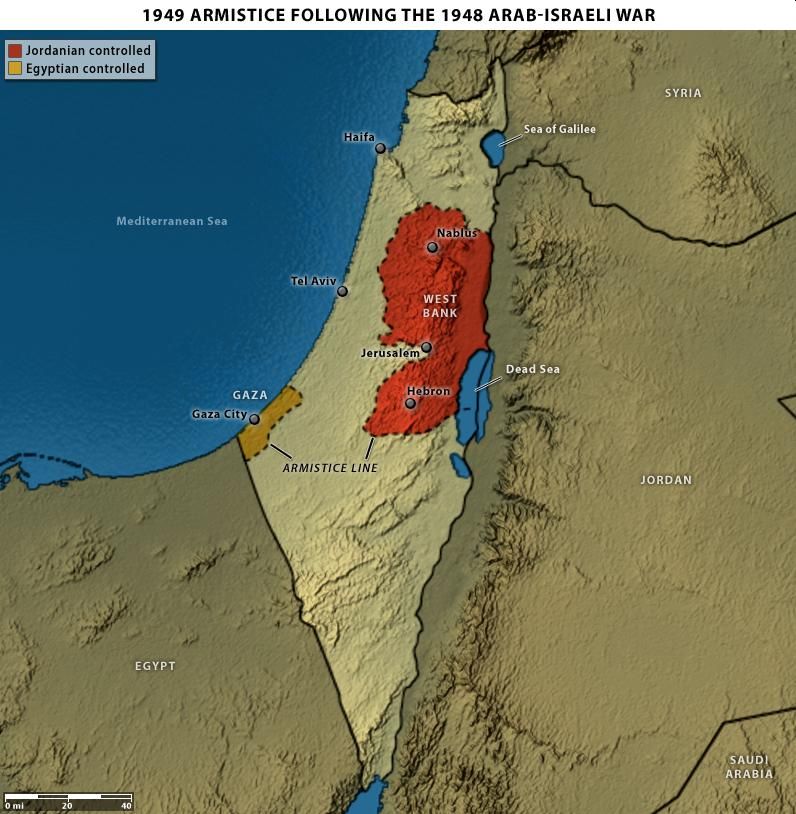

The Jordanian view of

the Palestinians was even more uncomfortable. The Hashemites were very

different from the region’s original inhabitants. After partitioning the

British-administered Palestine in 1948, Jordan took control of the West Bank

and East Jerusalem. But there were deep tensions with the Palestinians, and the

Hashemites saw Israel as a guarantor of Jordanian security against the Palestinians.

They never intended an independent Palestinian state (they could have granted

it independence between 1948 and 1967). In September 1970, they fought a bloody

war against the Palestinians, forcing the PLO out of Jordan and into Lebanon.

The Jordanians remain very fearful that the last vestige of the Hashemite

monarchy could collapse under the weight of Palestinians in the kingdom and the

West Bank, paving the way for a Palestinian takeover of Jordan.

The Egyptians also have been

uncomfortable with the Palestinians. Under the monarchy prior to the rise of

Gamal Abdul Nasser in 1952, Egypt was hostile to Israel’s creation. But when

the Egyptian army drove into what is now called Gaza in 1948, Cairo saw Gaza as

an extension of the Sinai Peninsula, as it saw the Negev Desert. It viewed the

region as an extension of Egypt, not a distinct state.

Nasser’s position was even more

radical. He envisioned a single, united Arab republic, both secular and

socialist. He thought of Palestine not as an independent state but as part of

the United Arab Republic (founded as a federation of Egypt and Syria from 1958

to 1961). Yasser Arafat was partly a creation of Nasser’s secular socialist

championing of Arab nationalism. The liberation of Palestine from Israel was

central to Arab nationalism, though this did not necessarily imply an

independent Palestinian republic.

Arafat’s role in defining the

Palestinians in the minds of Arab countries also must be understood. Nasser was

hostile to the conservative monarchies of the Arabian Peninsula. He intended to

overthrow them, knowing that incorporating them was essential to a united Arab

regime. These regimes, in return, saw Arafat,

the PLO, and the Palestinian movement as a direct threat.

Palestinian

nationalism represented a challenge to the Arab world as well: Syrian

nationalism, Jordanian nationalism, Nasser’s vision of a United Arab Republic,

and Saudi Arabia’s sense of security. If Arafat was the father of Palestinian

nationalism, then his enemies were not only the Israelis but also the Syrians,

the Jordanians, the Saudis, and, in the end, the Egyptians.

For updates click hompage here