By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

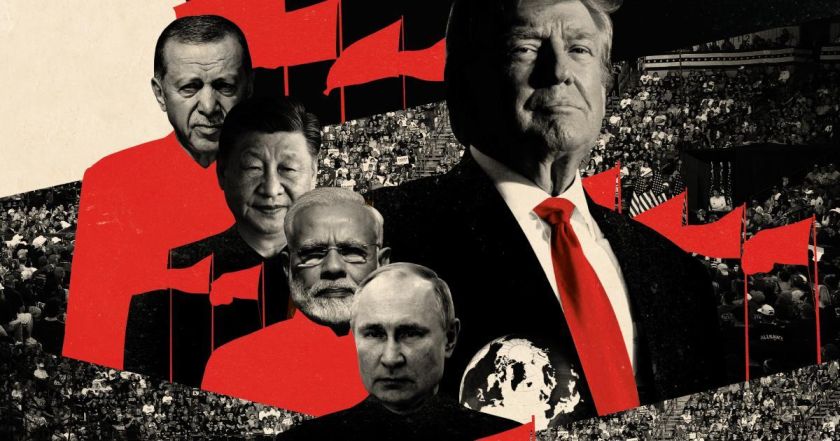

American Power in the New Age of

Nationalism

In the two decades

that followed the Cold War’s end, globalism

gained ground over nationalism. Simultaneously, the rise of increasingly

complex systems and networks—institutional, financial, and

technological—overshadowed the role of the individual in politics. But in the

early 2010s, a profound shift began. By learning to harness the tools of this

century, a cadre of charismatic figures revived the archetypes of the previous

one: the strong leader, the great nation, the proud civilization.

The shift arguably

began in Russia. In 2012, Vladimir Putin ended a short experiment

during which he left the presidency and spent four years as prime minister

while a compliant ally served as president. Putin returned to the top job and

consolidated his authority, crushing all opposition and devoting himself to

rebuilding “the Russian world,” restoring the great-power status that had

evaporated with the fall of the Soviet Union, and resisting the dominance of

the United States and its allies. Two years later, Xi Jinping made it to the

top in China. His aims were like Putin’s but far grander in scale—and China had

far greater capabilities. In 2014, Narendra Modi, a man with vast aspirations

for India, completed his long political ascent to the prime minister’s office

and established Hindu nationalism as his country’s dominant ideology. That same

year, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who had spent just over a decade as Turkey’s

hard-driving prime minister, became its president. In short order, Erdogan

transformed his country’s factionalized democratic ensemble into an autocratic

one-man show.

Perhaps the most

consequential moment in this evolution occurred in 2016 when Donald

Trump won the presidency of the United States. He promised to “make

America great again” and to put “America first”—slogans that captured a

populist, nationalist, anti-globalist spirit that had been percolating within

and outside the West even as the U.S.-led liberal international order took hold

and grew. Trump was not just riding a global wave. His vision of the U.S. role

in the world drew from specifically American sources, although less from the

original America First movement that peaked in the 1930s than from the

right-wing anticommunism of the 1950s.

For a while, Trump’s

loss to Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential race seemed to signal a

restoration. The United States was rediscovering its post–Cold War posture,

poised to buttress the liberal order and to stem the populist tide. In the wake

of Trump’s extraordinary comeback, however, it now appears more likely that

Biden, and not Trump, represented a detour. Trump and comparable tribunes of

national greatness are now setting the global agenda. They are self-styled

strongmen who place little stock in rules-based systems, alliances, or

multinational forums. They embrace the once and future glory of the countries

they govern, asserting an almost mystical mandate for their rule. Although

their programs can involve radical change, their political strategies rely on

strains of conservatism, appealing over the heads of liberal, urban,

cosmopolitan elites to constituencies animated by a hunger for tradition and a

desire for belonging.

In some ways, these

leaders and their visions evoke “the clash of civilizations” that the political

scientist Samuel Huntington, writing in the early 1990s, imagined would drive

global conflict after the Cold War. But they do so in a manner that

is often performative and flexible rather than categorical and overzealous. It

is the clash of civilizations lite: a series of gestures and a style of

leadership that can reconfigure competition over (and cooperation on) economic

and geopolitical interests as a contest among crusading civilization-states.

This contest is

rhetorical at times, allowing leaders to employ the language and the narratives

of civilization without having to stick to Huntington’s script or to the

somewhat simplistic divisions it foretold. (Orthodox Russia is at war with

Orthodox Ukraine, not with Muslim Turkey.) Trump was introduced at the 2020 GOP

convention as “the bodyguard of Western civilization.” The Kremlin leadership

has developed the notion of Russia as a “civilization-state,” using the term to

justify its efforts to dominate Belarus and subjugate Ukraine. At the 2024

Summit for Democracy, Modi characterized democracy as “the lifeblood of Indian

civilization.” In a 2020 speech, Erdogan declared that “our civilization is one

of conquest.” In a 2023 speech to the Central Committee of the Chinese

Communist Party, Chinese leader Xi Jinping extolled the virtues of a

national research project on the origins of Chinese

civilization, which he called “the only great, uninterrupted civilization

that continues to this day in a state form.”

In the years to come,

the kind of order these leaders fashion will greatly

depend on Trump’s second term. It was, after all, the U.S.-led order that had

encouraged the development of supranational structures following the Cold War.

Now that the United States has joined the twenty-first-century dance of nations,

it will often call the tune. With Trump in power, conventional wisdom in

Ankara, Beijing, Moscow, New Delhi, and Washington (and many other capitals)

will decree that there is no one system and no agreed-on set of rules. In this

geopolitical environment, the already tenuous idea of “the West” will recede

even further—and, consequently, so will the status of Europe, which in the

post–Cold War era had been Washington’s partner in representing “the Western

world.” European countries have been conditioned to expect U.S. leadership in

Europe and a rules-based order (not necessarily of American vintage) outside

Europe. Shoring up this order, which has been crumbling for years, will be left

to Europe, a loose confederation of states with no army and with little

organized hard power of its own—and whose countries

are experiencing a period of acutely weak leadership.

The Trump

administration has the potential to succeed in a revised international order

that has been years in the making. But the United States will thrive only if

Washington recognizes the danger of so many intersecting national fault lines

and neutralizes these risks through patient and open-ended diplomacy. Trump and

his team should regard conflict management as a prerequisite for American

greatness, not as an impediment to it.

The Real Roots of Trumpism

Analysts often

wrongly trace the origins of Trump’s foreign policy to the interwar years. When

the original America First movement flourished in the 1930s, the United

States had a modest military and did not have superpower status.

America Firsters wished more than anything to keep it

this way; they sought to avoid conflict. In contrast, Trump cherishes the

superpower status of the United States, as he emphasized repeatedly in his

second inaugural address. He is sure to increase military spending, and by

threatening to seize or otherwise acquire Greenland and the Panama Canal, he

has already proved that he will not shy away from conflict. Trump wants to

reduce Washington’s commitments to international institutions and to narrow the

scope of U.S. alliances, but he is hardly interested in overseeing an American

retreat from the global stage.

The true roots of

Trump’s foreign policy can be found in the 1950s. They emerge from that

decade’s surging anticommunism, although not from the liberal variant that

channeled democracy promotion, technocratic skill, and vigorous

internationalism, and that was championed by Presidents Harry Truman, Dwight

Eisenhower, and John F. Kennedy in response to the Soviet threat. Trump’s

vision stems from the right-wing anticommunist movements of the 1950s, which

pitted the West against its enemies, drew on religious motifs, and harbored a

suspicion of American liberalism as too soft, too postnational,

and too secular to protect the country.

This political legacy

is a tale of three books. First came Witness by the American

journalist Whittaker Chambers, a former communist and Soviet spy who eventually

broke with the party and became a political conservative. Witness was

his 1952 manifesto on fellow-traveling American liberals and their treachery,

which emboldened the Soviet Union. A similar vision motivated James Burnham,

the preeminent postwar conservative foreign-policy thinker. In his 1964 book, Suicide

of the West, he faulted the American foreign-policy establishment for

snobbish disloyalty and for upholding “principles that are internationalist and

universal rather than local or national.” Burnham advocated a foreign policy

built on “family, community, Church, country and, at the farthest remove,

civilization—not civilization in general but this historically specific

civilization, of which I am a member.”

One of Burnham’s

intellectual successors was a young journalist named Pat Buchanan. Buchanan

supported Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election, was an aide to

President Richard Nixon, and in 1992, launched a formidable primary challenge

to the sitting Republican president, George H. W. Bush. It is Buchanan whose

ideas most precisely foreshadow the Trump era. In 2002, Buchanan published The

Death of the West, in which he observed that “poor whites are moving

to the right” and contended that “the global capitalist and the true

conservative are Cain and Abel.” Despite the book’s title, Buchanan had some

hope for the West (in his us-and-them sense of the

term) and was confident in globalism’s impending crack-up. “Because it is a

project of elites, and because its architects are unknown and unloved,” he

wrote, “globalism will crash on the Great Barrier Reef of patriotism.”

Trump assimilated

this decades-long conservative tradition not through studying such figures but

through instinct and campaign-trail improvisation. Like Chambers, Burnham, and

Buchanan, outsiders enamored of power, Trump relishes iconoclasm and rupture, seeks

to upend the status quo, and loathes liberal elites and foreign-policy experts.

Trump may seem an unlikely heir to these men and the movements they shaped,

which were shot through with Christian moralism and at times with elitism. But

he has cannily and successfully cast himself not as a refined exemplar of

Western cultural and civilizational virtues but as their toughest defender from

enemies without and within.

The Revisionists

Trump’s dislike of

universalistic internationalism aligns him with Putin, Xi, Modi, and Erdogan.

These five leaders share an appreciation of foreign-policy limits and a nervous

inability to stand still. They are all pressing for change while operating within

certain self-imposed parameters. Putin is not trying to Russify the Middle

East. Xi is not trying to remake Africa, Latin America, or the Middle East in

China’s image. Modi is not attempting to construct ersatz Indias abroad. And

Erdogan is not pushing Iran or the Arab world to be more Turkish. Trump is

likewise uninterested in Americanization as a foreign-policy agenda. His sense

of American exceptionalism separates the United States from an intrinsically

un-American outside world.

Revisionism can

coexist with this collective avoidance of global system building and with the thinning

out of the international order. To Xi, history and Chinese power—not the UN

Charter or Washington’s preferences—are the true arbiters of Taiwan’s status,

for China is whatever he says it is. Although India does not sit beside a

global flash point like Taiwan, it continues to litigate its borders with China

and Pakistan, which have been unresolved since India achieved independence in

1947. India ends wherever Modi says it ends.

Erdogan’s revisionism

is more literal. To advantage its allies in Azerbaijan, Turkey facilitated

Azerbaijan’s expulsion of Armenians from the contested territory of

Nagorno-Karabakh, not through negotiation but through military force. Turkey’s

membership in the NATO alliance, which entails a formal commitment to democracy

and to the integrity of borders, did not stand in Erdogan’s way. Turkey has

also established itself as a military presence in Syria. This is not quite a

reconstitution of the Ottoman Empire. Erdogan does not aim to keep Syrian

territory in perpetuity. But Turkey’s military-political projects in the South

Caucasus and the Middle East have a historical resonance for Erdogan. Proof of

Turkey’s greatness, they show that Turkey will be wherever Erdogan says it

ought to be.

Amid this rising tide

of revisionism, Russia’s war against Ukraine is the central story. Acting in

the name of Russian “greatness” and presiding over a country that has no end in

his eyes, Putin’s speeches are awash in historical allusions. Sergey Lavrov,

the Russian foreign minister, once wisecracked that Putin’s closest advisers

are “Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and Catherine the Great.” But it is

the future, not the past, that really concerns Putin. Russia’s 2022 invasion

was a geopolitical turning point akin to those the world witnessed in 1914,

1939, and 1989. Putin waged war to partition or colonize Ukraine. He meant the

invasion to set a precedent that would justify similar wars in other theaters

and possibly excite other players (including China) about the possibilities of

disruptive military ventures. Putin rewrote the rules, and he has not ceased

doing so: badly as the invasion has gone for Russia, it has not resulted in

Russia’s global isolation. Putin has renormalized the idea of large-scale war

as a means of territorial conquest. He has done so in Europe, which once

epitomized the rules-based international order.

The war in

Ukraine, however, hardly augurs the death of international diplomacy. In some

ways, the war has kickstarted it. For example, the BRICS group, which formally

links China, India, and Russia (along with Brazil, South Africa, and other

non-Western countries) has grown larger and arguably more cohesive. On the

other side, Ukraine’s coalition of supporters has become far more than

transatlantic. It includes Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, and South

Korea. Multilateralism is alive and well; it is just not all-encompassing.

In this kaleidoscopic

geopolitical landscape, relationships are protean and

complex. Putin and Xi have built a partnership but not quite an alliance. Xi

has no reason to imitate Putin’s reckless break with Europe and the United

States. Despite being rivals, Russia and Turkey can at least deconflict their

actions in the Middle East and in the South Caucasus. India regards China

apprehensively. And although some analysts have taken to describing China,

Iran, North Korea, and Russia as forming an “axis,” they are four profoundly

different countries whose interests and worldviews frequently diverge.

The foreign policies

of these countries emphasize history and uniqueness, the notion that

charismatic leaders must heroically uphold Russian or Chinese or Indian or

Turkish interests. This militates against their convergence and makes it hard

for them to form stable axes. An axis requires coordination, whereas the

interaction among these countries is fluid, transactional, and personality-driven. Nothing here is black and white, nothing

is set in stone, and nothing is nonnegotiable.

This milieu suits

Trump perfectly. He is not overly constrained by religiously and culturally

defined fault lines. He often prizes individuals over governments and personal

relationships over formal alliances. Although Germany is a NATO ally

of the United States and Russia a perennial adversary, Trump clashed with

German Chancellor Angela Merkel in his first term and treated Putin with

respect. The countries Trump wrestles with the most are those that lie within

the West. Had Huntington lived to see this, he would have found it baffling.

A Vision of War

In Trump’s first

term, the international landscape was fairly calm.

There were no major wars. Russia appeared to have been contained in Ukraine.

The Middle East appeared to be entering a period of relative stability

facilitated in part by the Trump administration’s Abraham Accords, a set of

deals intended to enhance regional order. China appeared to be

deterrable in Taiwan; it never came close to invading. Indeed

if not always in word, Trump conducted himself as a typical Republican

president. He increased U.S. defense commitments to Europe, welcoming two new

countries into NATO. He struck no deals with Russia. He talked harshly about

China, and he maneuvered for advantage in the Middle East.

But today, a major

war rages in Europe, the Middle East is in disarray, and the old international

system is in tatters. A confluence of factors might lead to disaster: the

further erosion of rules and borders, the collision of disparate

national-greatness enterprises supercharged by erratic leaders and by

rapid-fire communication on social media, and the mounting desperation of

medium-sized and smaller states, which resent the unchecked prerogatives of the

great powers and feel imperiled by the consequences of international anarchy. A

catastrophe is more likely to erupt in Ukraine than in Taiwan or the Middle

East because the potential for world war and for nuclear war is greatest in

Ukraine.

Even in the

rules-based order, the integrity of borders has never been absolute—especially

the borders of countries in Russia’s vicinity. But since the end of the Cold

War, Europe and the United States have remained committed to the principle of

territorial sovereignty. Their enormous investment in Ukraine honors a

distinctive vision of European security: if borders can be altered by force,

Europe, where borders have so often generated resentment, would descend into

all-out war. Peace in Europe is possible only if borders are not easily

adjustable. In his first term, Trump underscored the importance of territorial

sovereignty, promising to build a “big, beautiful wall” along the U.S. border

with Mexico. But in that first term, Trump did not have to contend with a major

war in Europe. And it’s clear now that his belief in the sanctity of borders

applies primarily to those of the United States.

Trump and Modi in New Delhi, February 2020

China and India,

meanwhile, have reservations about Russia’s war, but along with Brazil, the

Philippines, and many other regional powers, they have made a far-reaching

decision to retain their ties with Russia even as Putin labors away at

destroying Ukraine. Ukrainian sovereignty is immaterial to these “neutral”

countries, unimportant compared with the value of a stable Russia under Putin

and with the value of continuing energy and arms deals.

These countries may

underestimate the risks of accepting Russian revisionism, which could lead not

to stability but to a wider war. The spectacle of a carved-up or defeated

Ukraine would terrify Ukraine’s neighbors. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and

Poland are NATO members that take comfort in NATO’s Article 5 commitment to

mutual defense. Yet Article 5 is underwritten by the United States—and the

United States is far away. If Poland and the Baltic republics concluded that

Ukraine was on the brink of a defeat that would put their own sovereignty at

risk, they might elect to join the fight directly. Russia might respond by

taking the war to them. A similar outcome could result from a grand bargain

among Washington, western European countries, and Moscow that ends the war on

Russian terms but has a radicalizing effect on Ukraine’s neighbors. Fearing

Russian aggression on the one hand and the abandonment of their allies on the

other, they could go on the offensive. Even if the United States stayed on the

sidelines amid a Europe-wide war, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom would

probably not remain neutral.

Were the war in

Ukraine to widen in that way, its outcome would greatly affect the reputations

of Trump and Putin. Vanity would exert itself, as it so often does in

international affairs. Just as Putin cannot afford to lose a war to Ukraine,

Trump cannot afford to “lose” Europe. To squander the prosperity and power

projection that the United States gains from its military presence in Europe

would be humiliating for any American president. The psychological incentives

for escalation would be strong. And in a highly personalistic international

system, especially one agitated by undisciplined digital diplomacy, such a

dynamic could take hold elsewhere. It could spark hostilities between China and

India, perhaps, or between Russia and Turkey.

A Vision of Peace

Alongside such

worst-case scenarios, consider how Trump’s second term could also improve a

deteriorating international situation. A combination of workmanlike U.S.

relations with Beijing and Moscow, a nimble approach to diplomacy in

Washington, and a bit of strategic luck might not necessarily lead to

breakthroughs, but it could produce a better status quo. Not an end to the war

in Ukraine, but a reduction in its intensity. Not a resolution of the Taiwan

dilemma, but guardrails to prevent a major war in the Indo-Pacific. Not a

solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but some

form of U.S. detente with a weakened Iran and the emergence of a viable

government in Syria. Trump might not become an unqualified peacemaker, but he

could help usher in a less war-torn world.

Under Biden and his

predecessors, Barack Obama and George W. Bush, Russia and China had to cope

with systemic pressure from Washington. Moscow and Beijing stood outside the

liberal international order in part by choice and in part because they were not

democracies. Russian and Chinese leaders exaggerated this pressure, as if

regime change were actual U.S. policy, but they were not wrong to detect a

preference in Washington for political pluralism, civil liberties, and the

separation of powers.

With Trump back in

office, that pressure has dissipated. The form of the governments in Russia and

China does not preoccupy Trump, whose rejection of nation building and regime

change is absolute. Even though the sources of tension remain, the overall atmosphere

will be less fraught, and more diplomatic exchanges may be possible. There may

be more give-and-take within the Beijing-Moscow-Washington triangle, more

concessions on small points, and more openness to negotiation and to

confidence-building measures in zones of war and contestation.

If Trump and his team

can practice it, flexible diplomacy—the deft management of constant tensions

and rolling conflicts—could pay big dividends. Trump is the least Wilsonian

president since Woodrow Wilson himself. He has no use for overarching structures

of international cooperation such as the UN or the Organization for Security

and Cooperation in Europe. Instead, he and his advisers, especially those who

hail from the tech world, might approach the global stage with the mentality of

a start-up, a company just formed and perhaps soon to be dissolved but able to

react quickly and creatively to the conditions of the moment.

Ukraine will be an

early test. Instead of pursuing a hasty peace, the Trump administration should

stay focused on protecting Ukrainian sovereignty, which Putin will never

accept. To allow Russia to curtail Ukraine’s sovereignty might provide a veneer

of stability but could bring war in its wake. Instead of an illusory peace,

Washington should help Ukraine determine the rules of engagement with Russia,

and through these rules, the war could gradually be minimized. The United

States would then be able to compartmentalize its relations with Russia, as it

did with the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War, agreeing to disagree about

Ukraine while looking for possible points of agreement on nuclear

nonproliferation, arms control, climate change, pandemics, counterterrorism,

the Arctic, and space exploration. The compartmentalization of conflict with

Russia would serve a core U.S. interest, one that is dear to Trump: the

prevention of a nuclear exchange between the United States and Russia.

A spontaneous style

of diplomacy can make it easier to act on strategic luck. The revolutions in

Europe in 1989 offer a good example. The dissolution of communism and the

collapse of the Soviet Union have sometimes been interpreted as a masterstroke

of U.S. planning. Yet the fall of the Berlin Wall that year had little to do

with American strategy, and the Soviet disintegration was not something the

U.S. government expected to happen: it was all

accident and luck. President George H. W. Bush’s national security team was

superb not at predicting or controlling events but at responding to them, not

doing too much (antagonizing the Soviet Union) and not doing too little

(letting a united Germany slip out of NATO). In this spirit, the Trump

administration should be primed to seize the moment. To make the most of

whatever opportunities come its way, it must not get bogged down in system and

in structure.

But taking advantage

of lucky breaks requires preparation as well as agility. In this regard, the

United States has two major assets. The first is its network of alliances,

which greatly magnifies Washington’s leverage and room to maneuver. The second

is the American practice of economic statecraft, which expands U.S. access to

markets and critical resources, attracts outside investment, and maintains the

American financial system as a central node of the global economy.

Protectionism and coercive economic policies have their place, but they should

be subordinate to a broader, more optimistic vision of American prosperity, and

one that privileges long-time allies and partners.

None of the usual

descriptors of world order apply anymore: the international system is not

unipolar or bipolar or multipolar. But even in a world without a stable

structure, the Trump administration can still use American power, alliances,

and economic statecraft to defuse tension, minimize conflict, and furnish a

baseline of cooperation among countries big and small. That could serve Trump’s

wish to leave the United States better off at the end of his second term than

it was at the beginning.

For updates click hompage here