By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Harry Truman's character and view of the world

were different from Franklin Roosevelt's. Yet it must not be thought that

his sudden assumption of the presidency meant an instant change in America's

relations with Russia. True, when Truman received Molotov in the White House

less than ten days after he had become president, he spoke to this Russian in

solid words to which the latter said that he was thoroughly unaccustomed.

Truman's advisers instantly thought that the president's language was too

harsh, and the next day Truman thought it better not to press the issue (again,

it was mostly Poland) with Molotov. When Churchill, a few days after the German

surrender, implored Truman to take a harder line with Moscow (it was in that

letter that Churchill first used the phrase iron curtain), Truman did not

follow Churchill's urgings; another few days later, he sent Joseph Davies and

then Harry Hopkins to Moscow to try to iron out problems with

Stalin. During the Potsdam summit meeting in July,

Truman's behavior and his impressions of Stalin were still cordial and

positive.

Throughout 1945 (and even for two years after that), Truman did not

altogether abandon the hope of maintaining at least good relations with the

Soviet Union, and particularly with Stalin.

However, he had, commendably, few or no illusions about Stalin or

Russian ambitions or Communism. The following year, 1946, was marked by more

and more troubles with Russians and Communists, involving Iran, Turkey, Greece,

Yugoslavia, Berlin. In March 1946, Truman accompanied Churchill to Fulton,

Missouri, where Churchill delivered his famous Iron

Curtain speech (though the president and the State Department were careful

to state publicly that they were not necessarily associating themselves with

the former prime minister's views). By early 1947 Truman's decision was to

oppose further Soviet advances and aggressions and contain the Soviet Union and

Communism. By that time, Stalin had decided to proceed to the more or less

complete Communization of the countries that had fallen into his sphere of

interest in Eastern Europe. There was, as yet, no sharp conflict between the

Soviet Union and the United States in China or the Pacific.

Truman believed in American power and American righteousness. So did

his newly appointed secretary of state, James F. Byrnes. Byrnes was a longtime

Washington power broker, a former conservative senator from South Carolina,

Supreme Court justice, and wartime overlord of the American economy. Truman

liked Byrnes, who had befriended him as a new senator in the mid-1930s, and

thought him shrewd, knowledgeable, and challenging. He let Byrnes do most of

the contentious bargaining at Potsdam on German reparations, Polish borders,

and the composition of the new governments in Eastern Europe. Once Stalin

agreed in the first days of the conference to attack Japan, Truman felt

satisfied. "I've gotten what I came for," he confided to Bess on July

18. "Stalin goes to war August 15 with no strings on it. ... I'll say that

we'll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won't be killed.

That's the important thing."

To Truman and Byrnes, the atomic bomb meant more than the weapon to

defeat Japan and save American lives. It was a vast new instrument of American

power. Truman went to Potsdam not knowing it would work; Admiral Leahy said it

wouldn't; Byrnes thought it might, "but he wasn't sure." By all

accounts, and there are many, news of the successful testing of the bomb

enormously buoyed Truman's self-confidence. It "took a great load off my mind," he confided

to Joe Davies. The president did not order the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima

to impress the Russians, as some historians claim; nevertheless, he believed

that it would impress them and make them more manageable.

Truman quietly took Stalin aside at Potsdam and elliptically mentioned

that the United States had a powerful new weapon to use against Japan. Nothing

more needed to be said. Nor did all the pressing issues have to be resolved at

Potsdam. Truman was eager to go home. He grew impatient with the incessant

haggling at the conference. Stalin, he thought, was stalling. He "doesn't

know it," Truman again wrote his wife, "but I have an ace in the hole

and another one showing-so unless he has threes or two pairs (and I know he has

not), we are sitting all right." The

"atomic bomb," Byrnes also was thinking, "had given us great

power, and ... in the last analysis, it would control."

When Truman ordered that atomic bombs be dropped on Hiroshima and then

Nagasaki, these were not tough decisions. They were necessary, in his mind, to

save American lives. They vividly demonstrated American power; they confirmed

that enemies of America would pay for their transgressions. The Japanese did

pay, and then they capitulated unconditionally, except for the preservation of

the emperor. They had little choice, for Stalin's troops attacked

simultaneously, seized parts of Manchuria, invaded northern Korea, and set

their sights on Hokkaido, Japan's northernmost home island.

The war ended. The American people celebrated. Truman breathed a sigh

of relief. He now eagerly delegated peacemaking to Secretary of State Byrnes,

who he thought had performed ably at Potsdam. Truman wanted to turn his

attention to demobilization, reconversion, and the domestic issues he knew and

understood. Byrnes, for his part, was eager to take command of the nation's

foreign policy. He was sure of himself. He told his closest colleagues that the

atomic bomb was a great weapon that could be used to exact concessions from

potential adversaries. But experienced colleagues in the State and War

departments had their doubts. They deeply resented Byrnes's attempts to

monopolize American diplomacy. Many of them left office in September and

October 1945; however, Byrnes was in charge, exhausted from years of wartime

responsibility.

Byrnes was not as shrewd as he thought he was, nor was the Soviet Union

quickly threatened. At the first postwar meeting of foreign ministers in London

in September, Byrnes thought he could outmaneuver Molotov and arrange for more

representative governments in Romania and Bulgaria. But Molotov chafed at

Byrnes's procedural moves and sneered at his not very subtle efforts to use

America's atomic monopoly to leverage concessions. The Soviet foreign minister

was willing to negotiate on some of these points until Stalin ordered him to

stiffen his resolve. Let the conference end in deadlock, Stalin wired Molotov.

Let Byrnes stew for a while. Stalin's adulatory comments about Byrnes in front

of Truman at Potsdam had, typically, concealed the dictator's emerging contempt for a man who wielded power so flagrantly.

Byrnes returned to Washington chastened. The Russians would not be

intimidated, he realized. Perhaps, Byrnes now thought, the bomb could be used

as a carrot rather than a stick. Maybe the Soviets could be lured into a

favorable agreement to regulate the future of atomic energy. Some of the

Soviets' arguments, he believed, had merit. He conceded certain hypocrisy in

the American insistence that the Soviets open up eastern Europe while the

United States locked the Kremlin out of Japan. He could understand why the

Soviets feared the revival of German power and wanted friendly governments on

their periphery. It might make sense, he thought, to acquiesce to what was

happening in Bulgaria and Romania, more or less, if, in return, the Kremlin

promised to withdraw Soviet troops as soon as the peace treaties were

negotiated.

Moreover, a four-power treaty guaranteeing the demilitarization of

Germany might hasten this process. In other words, Stalin's obsession with

security might be assuaged by a demilitarization treaty. At the same time, his

domination of eastern Europe might be diluted by his agreement to withdraw

Soviet troops from Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, as they just had been

removed from Czechoslovakia.

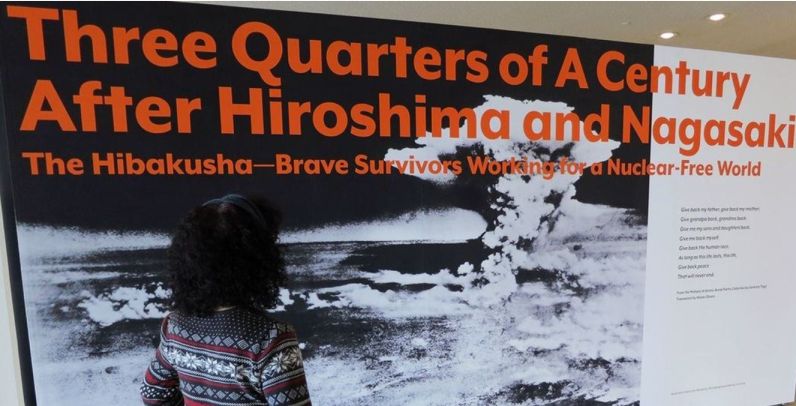

An example from the WWII era of the rewriting of history is President

Truman's decision in August 1945 to drop atomic bombs on Japanese cities. As a

result of the president's decision, over 200,000 Japanese civilians were

slaughtered. This decision was justified at the time as necessary to prevent

the deaths of tens of thousands of American soldiers that would ensue from an

invasion of the Japanese islands.

President Truman decided to detonate atomic bombs over Hiroshima on

August 6, 1945, and Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, without consulting broadly with

his advisors.1 The majority of the members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff did not

believe at the time that dropping atomic bombs on Japan was warranted: Of the

eight five-star generals in the US military, only one – Marshall - thought the

bombing was justified.2 Postwar appraisals of Truman's decision by the leading

generals of the US military - Arnold, Eisenhower, Halsey, King, Leahy,

MacArthur, and Nimitz - concluded that dropping nuclear bombs on Japan was

unnecessary.3

There are several reasons for this consensus against dropping atomic

bombs on Japan among military leaders. Both American and Japanese officials

understood by the summer of 1945 that Japan had lost the war. The US military

had total, unopposed control of the skies and had blockaded the main Japanese

island. Because of the Allied bombing and the blockade, the Japanese government

had been rationing food since early 1945, but supplies were expected to run out

by November.4 In fact, the emperor feared that if the war did not end soon, a

domestic revolt would overthrow his dynasty.5

The Soviet Union was poised to invade the Japanese homeland to the

west.6 The Japanese particularly feared Russian occupation. Admiral Toyoda said

in a postwar statement that "the Russian participation in the war against

Japan rather than the atom bombs did more to hasten the surrender."

7

Recognizing the inevitable, Japanese officials had made numerous

overtures to the US government.8 Throughout 1945, the emperor and his advisors

sought assistance from Sweden and Portugal to negotiate a peace treaty with the

United States. On May 5, a cable from a member of the Admiral Staff of the

Japanese Navy stated that much of the Japanese military "would not regard

with disfavor an American request for capitulation even if the terms were

hard." 9 On July 13, another cable from the Japanese foreign minister

reported that the emperor was "mindful of the fact that the present war

daily brings greater evil and sacrifice upon the people of all belligerent

powers," and that he "desires from his heart that it might be quickly

terminated." 10

After Japan's surrender, Secretary of War Stimson commissioned an

interrogation of some seven hundred Japanese military, government, and industry

officials and concluded that "before December 31, 1945, and in all

probability before November 1, 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the

atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and

even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated." 11 Truman was aware

of the Japanese overtures and the content of the diplomatic cables. But Truman

did not respond to any of them.12

Despite what is written in most American textbooks, there were

alternatives to dropping atomic bombs on large population centers that

incinerated and fatally poisoned hundreds of thousands of civilian men, women,

and children. In our view, the best option would have been to wait. Stalin had

committed to Truman to declare war on Japan on August 15, including announcing

an invasion of the Japanese islands. The looming prospect of a Soviet invasion

might have prompted an immediate Japanese surrender. And Truman did not have to

drop the second bomb soon after the first. It was impractical for Japan to

negotiate a surrender with an unresponsive US president in the seventy-five

hours between the detonation of the first and second atomic bombs.

Of course, it cannot be known for sure how long Japan may have delayed

negotiating a surrender to end the war without the bombing of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. The Japanese military was divided. Some wanted to fight on, but many

were willing to accept a peace that maintained the emperor's dynasty. (While

Truman demanded unconditional surrender, the United States supported the

Imperial Dynasty after the war, and the emperor's grandson sits on the Japanese

throne today.) The Japanese also knew that an invasion would likely cost tens

of thousands of American lives and believed this grim prospect gave them

negotiating leverage. And Japanese scientists at the time had correctly guessed

that the United States had only a few atomic bombs in early August. (A third bomb

would have been ready by August 21, and more would have followed in September.)

13

In any case, an invasion of the Japanese mainland would have occurred

at the earliest in late October or early November.14 Given the collapse of food

supplies, the threat of an overthrow of the Imperial Dynasty, and a threatened

Soviet invasion and occupation, a delay of even several weeks may have resulted

in a Japanese surrender. At a minimum, Truman could have paused for more than

seventy-five hours before dropping the second atomic bomb.

The fact is that Truman did not hesitate to order the detonation of all

the atomic bombs in the military's possession as soon as they were ready. But

it is doubtful the Japanese regime could have survived more than several months

without negotiating an end to the war. Hundreds of thousands of lives might

have been saved if Truman had delayed the detonation of atomic bombs over

Japanese cities until just before a planned invasion of the Japanese islands

later in the year. And Truman could have responded to the Japanese entreaties

for surrender.

But he did not. There is no evidence Truman considered even a short

delay or the possibility of peace.15

On August 9, after A second atomic bomb had incinerated Nagasaki,

Truman received a telegram from a Protestant clergyman, pleading with him to

stop the bombing. Truman's racist attitude toward the Japanese was no secret.

Truman replied, "When you have to deal with a beast, you have to treat him

as a beast." 16

The version of history recorded in most American history textbooks and

commonly repeated today is that the decision to drop bombs on Hiroshima and

Nagasaki in August was justified to avoid further American casualties. But

Truman could have waited, even for just a few weeks, and that might have saved

the lives of over 200,000 Japanese people. It might have even delayed the start

of the Cold War and the nuclear arms race that followed.

1. Background on the

decision to drop two atomic bombs on Japan comes from Huczko

(2014); Maciej. (2014. “Alternatives to Dropping the A-Bomb in Bringing the War

with Japan to an End.” Warsaw School of Economics. Vol. 1. No. 39. p. 128–137.

2. Ellsberg (2017),

Ellsberg, Daniel, (2017). The Doomsday Machine, Bloomsbury Publishing, New

York, Daniel, (2017). The Doomsday Machine, Bloomsbury Publishing, New York.

3. Frank (1999), and

Alperovitz (1995). Frank, Richard, (1999), Downfall, Penguin Books, New York,

Alperovitz, Gar. (1995). The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb. Alfred A. Knopf,

Inc. New York.

4. The role of the

emperor and the Japanese government at the time comes from Bix (2000) and

Laquerre (2013).

5. Huczko (2014). “Alternatives to Dropping the A-Bomb in

Bringing the War with Japan to an End.” Warsaw School of Economics. Vol. 1. No.

39. p. 128–137.

6. Frank (1999),

Downfall, Penguin Books. New York.

7. Ellsberg (2017),

The Doomsday Machine, Bloomsbury Publishing. New York.

8. Huczko (2014), p. 133.

9. Huczko (2014), p. 131.

10. Huczko (2014), p. 131.

11. Frank (1999), p.

355.

12. Huczko (2014), p. 131.

13. Frank (1999), p. 303.

14. Frank (1999), p. 358.

15. Frank (1999), p.

303.

16. National Park

Service (2017). Bix, Herbert, (2000), Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan.

Harper Collins, New York.

For updates click hompage here