By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

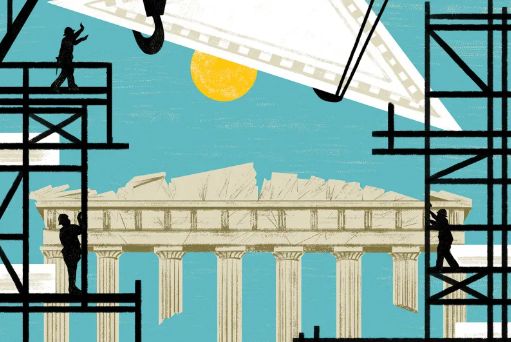

The Right Way to Counter Autocracy

When U.S. President

Joe Biden took office in January 2021, the United States had just witnessed four

of the most turbulent years in recent memory, culminating in the failed

insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6. Without a doubt, American

democracy was far more fragile than when Biden left the vice presidency in

2017.

The picture abroad

wasn’t much brighter. Populist parties with xenophobia and antidemocratic

tendencies were gaining momentum in established and nascent democracies. The

world’s autocracies seemed newly emboldened. Russia was clamping down on

dissent at home and encouraging authoritarianism abroad through election

interference, disinformation campaigns, and the actions of its paramilitary

Wagner Group. Meanwhile, China’s government had become even more repressive at

home and more assertive abroad, stripping Hong Kong of its autonomy and

leveraging its vast bilateral financial investments to secure support for its

policies in international institutions. In February 2022, just three weeks

before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Chinese President Xi

Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a new

strategic partnership that they claimed would have “no limits.”

But early 2022 may

prove to be a high-water mark for authoritarianism. Putin made a mistake

after a strategic error while the free people of Ukraine successfully

mobilized, innovated, and adapted.

The root causes of

Moscow’s disastrous showing are numerous, but several bears the hallmarks of

authoritarianism. Graft has rotted the Russian military from within, yielding

reports of soldiers selling fuel and weapons on the black market. Russian

commanders have taken massive risks with the lives of their soldiers:

conscripts arrive at the front having been lied to and manipulated rather than

properly trained. To avoid upsetting their superiors, military leaders have

supplied overly rosy assessments of their ability to conquer Ukraine, leading

one pro-Russian militia commander to call self-deception “the herpes of the

Russian army.”

Russia’s ghastly

conduct in Ukraine has left Moscow more isolated than ever since the end of

the Cold War. Most European countries are racing to decouple their

economies from Russia, and Finland and Sweden are on the brink of joining an

expanded and united NATO. Public opinion of Russia and Putin has plummeted

worldwide, reaching record lows, according to the Pew Research Center. In

Russia’s immediate neighborhood, Moscow’s traditional security and economic

partners are staying neutral, refusing to host joint military exercises,

seeking to reduce their economic dependence on Russia, and upholding the

sanctions regimes. Russians themselves are voting with their feet: officially,

hundreds of thousands of citizens have fled, but the actual number is

likely well over one million and includes tens of thousands of valued high-tech

workers.

The past few years

have also demonstrated the shortcomings of Beijing’s model. In 2020 and 2021,

senior Chinese officials claimed that the global response to

the COVID-19 pandemic showed the superiority of their system.

They regularly took potshots at the United States for its high COVID-19 death

toll. Unquestionably, the United States and other democracies made mistakes in

handling COVID-19. But unlike Chinese citizens, dissatisfied voters in

these countries could elect new leaders and change their governments’ approach

to the pandemic. By contrast, Beijing withheld vital data from the World Health

Organization, refused to work with other nations in developing a vaccine, and

stuck with its harsh “zero COVID” policy until late 2022. It

continues to be opaque about the COVID-19 situation in China, limiting the

international community’s understanding of potential variants.

Elsewhere, public

support for populist parties, leaders, and antipluralist

attitudes has dropped significantly since 2020, partly because populist-led

governments mishandled the pandemic. Between mid-2020 and the end of 2022,

populist leaders saw an average decline of 10 percentage points in their

approval ratings in 27 countries analyzed by researchers at Cambridge

University. In the same time frame, prominent leaders with autocratic

tendencies lost power at the ballot box. And American democracy has proved

resilient; the U.S. Congress passed meaningful electoral reforms and held

powerful public investigations into the events leading up to January 6.

Autocrats are now on

the back foot. Under Biden’s leadership, the United States and

countries worldwide have joined forces to protect and strengthen democracy at

home and abroad and to work together on challenges such as climate change and

corruption. After a year of faltering authoritarianism and stubborn democratic

resilience, the United States and other democracies can regain their

momentum—but only if we learn from the past and adapt our strategies. For the

last three decades, advocates of democracy have focused too narrowly on

defending rights and freedoms, neglecting the pain and dangers of economic

hardship and inequality. We have also failed to contend with the risks

associated with new digital technologies, including surveillance technologies,

that autocratic governments have learned to exploit to their advantage. It

is time to coalesce around a new agenda for aiding the cause of global freedom,

one that addresses the economic grievances that populists have so effectively

exploited, defangs so-called digital authoritarianism, and reorients

traditional democracy assistance to grapple with modern challenges.

Not A Fragile Flower

In his address to the

British Parliament in 1982, U.S. President Ronald Reagan observed

that “democracy is not a fragile flower; still, it needs cultivating.” Since

then, the cultivation of democracy abroad has largely meant the provision of

what we call democracy assistance: funding to support independent media, the

rule of law, human rights, good governance, civil society, pluralistic

political parties, and free and fair elections.

This assistance from

the United States, which grew from just over $106 million in 1990 to over $520

million in 1999, supported democratic actors in countries locked behind the

Iron Curtain as they became proud, thriving members of a free Europe. After

brave protesters broke the grip of Soviet rule, our assistance helped newly

independent countries establish everything from public broadcasters to

independent judiciaries. Similar initiatives aided reformers throughout Africa,

Asia, and Latin America as they solidified their democracies.

Although it is

difficult to measure how much these programs have advanced democratic progress worldwide,

multiple studies have identified ways in which democracy assistance from the

United States and other donors has supported positive outcomes. The U.S. Agency

for International Development, the institution I lead and the largest provider

of democracy assistance in the world, has had “clear and consistent impacts” on

civil society, judicial and electoral processes, media independence, and

overall democratization, according to one study of the agency’s democracy

promotion programs between 1990 and 2003. A later study

commissioned by USAID found that every $10 million of democracy

assistance it provided between 1992 and 2000 contributed to a seven-point jump

on the 100-point global electoral democracy index maintained by the nonprofit Varieties

of Democracy.

But the same study

showed that these positive effects began to falter in the years after

the 9/11 attacks on the United States. Between 2001 and 2014, the

same amount of investment only saw an increase of a third of a point—still two

and a half times more than the average annual change among countries in the

electoral democracy index over that period, but a much more diminished impact

than in previous years.

Of course, a host of

interrelated factors contribute to democracy’s struggles: polarization,

significant inequality, widespread economic dissatisfaction, the explosion of

disinformation in the public sphere, political gridlock, the rise of China as

a strategic competitor of the United States, and the spread of digital

authoritarianism aimed at repressing free expression and expanding government

power. Many of these challenges can only be solved domestically. But those

of us invested in the global renewal of democracy must help societies address

economic concerns that antidemocratic forces have exploited; take the fight for

democracy into the digital realm, just as autocracies have; and adapt our

toolkit to meet not just long-standing challenges to democracy but also new

ones.

Blinded By The Rights

At the core of

democratic theory and practice is respect for the individual's dignity. But

among the most significant errors many democracies have made since the Cold War

is to view individual dignity primarily through the prism of political freedom

without being sufficiently attentive to the indignity of corruption,

inequality, and a lack of economic opportunity.

This was not a

universal blind spot: several political figures, advocates, and individuals

working at the grassroots level to advance democratic progress presciently

argued that economic inequality could fuel the rise of populist leaders and

autocratic governments that pledged to improve living standards even as they

eroded freedoms. But too often, the activists, lawyers, and other members

of civil society who worked to strengthen democratic institutions and protect

civil liberties looked to labor movements, economists, and policymakers to

address economic dislocation, wealth inequality, and declining wages rather

than building coalitions to tackle these intersecting problems.

Democracy suffered as

a result. Over the past two decades, as economic inequality rose, polls

showed that people in rich and poor countries alike began to lose faith in

democracy and worry that young people would end up worse off than they were,

giving populists and ethnonationalists an opening to exploit grievances and

gain a political foothold on every continent.

Moving forward, we

must look at all economic programming that respects democratic norms as a form

of democratic assistance. When we help democratic leaders provide vaccines

to their people, bring down inflation or high food prices, send children to

school, or reopen markets after a natural disaster, we are demonstrating—in a

way that a free press or vibrant civil society cannot always do—that democracy

delivers. And we are making it less likely that autocratic forces will take

advantage of people’s economic hardship.

Nowhere is that task

more important today than in societies that have managed to elect democratic

reformers or throw off autocratic or antidemocratic rule through peaceful mass

protests or successful political movements. These democratic bright spots are

incredibly fragile. Unless reformers solidify their democratic and economic

gains quickly, populations understandably grow impatient, especially if they

feel that the risks they took to upend the old order have not yielded

tangible dividends in their own lives. Such discontent allows opponents of

democratic rule—often aided by external autocratic regimes—to wrest back

control, reversing reforms and snuffing out dreams of rights-regarding

self-government.

The task before reformist

leaders is enormous. Often they inherit budgets laden with debt; economies

hollowed out by corruption, civil services built on patronage, or a combination

of all three. When Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema took office in

2021 after winning a landslide victory over an incumbent whose regime had

arrested him more than a dozen times, he discovered that his predecessors

had accumulated over $30 billion in unserviceable debt, nearly one and a half

times the country’s GDP, with very little new infrastructure or

return on borrowing to show for it. In Moldova, where the anticorruption

advocate Maia Sandu was elected president in 2020, a

single corruption scandal had previously siphoned off a whopping 12 percent of

the country’s GDP.

Election Day In Chisinau, Moldova

To help rising

democracies overcome such hurdles, USAID has stepped up with

additional support. We have identified and increased our investment in several

bright democratic spots, including the Dominican Republic, Malawi, the

Maldives, Moldova, Nepal, Tanzania, and Zambia. That list is by no means

comprehensive, and admittedly some of these bright spots shine more intensely

than others in their commitment to democratic reform. But all are working to

fight corruption, create more space for civil society, and respect the

rule of law. Biden has also created a special fund at USAID so we can

move quickly to help bright spots deliver on their key economic priorities as they

pursue reforms and consolidate democratic gains.

But we don’t just

want to boost our assistance to these countries; we want to help them

prosper beyond the impact of our programming. The U.S. government’s flagship

food security initiative, Feed the Future, which works with agribusiness,

retailers, and university research labs to help countries improve their

agricultural productivity and exports, recently expanded to include Malawi and

Zambia. USAID has also partnered with Vodafone to expand the reach of a

mobile app called m-mama to every region in Tanzania. The app is akin to an

Uber for expectant mothers, helping pregnant women who lack ambulance services

reach health facilities and significantly decreasing maternal mortality. In

Moldova, pushing ahead with anticorruption reforms despite ramped-up economic

pressure from Russia, USAID has worked to increase the country’s

trade integration with Europe. And at the UN General Assembly in

September, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and I gathered the

heads of state of many of these rising democracies, together with

corporate executives and private philanthropies, to encourage new

partnerships.

Principled Aid

Everywhere they

assist, democratic countries must be guided by and seek to promote democratic

principles—including human rights, norms that counter corruption, and

environmental and social safeguards. In contrast to the approach of autocratic

governments, we showcase the potential benefits of our democratic system when

we assist in a fair, transparent, inclusive, and participatory

manner—strengthening local institutions, employing local workers, respecting

the environment, and providing benefits equitably in society.

Over the past four

decades, Beijing has transformed from one of the largest recipients of foreign

assistance to the largest bilateral provider of development finance, mainly in

the form of loans. Through its enormous infrastructure investments, Beijing has

helped many developing countries build seaports, railways, airports, and

telecommunications infrastructure. But the second-order effects of China’s

financing can undermine the long-term development objectives of partner

countries and the health of their institutions. Even in highly indebted poor

countries, much of the development financing China offers is provided at

non-concessional market rates through opaque agreements hidden from the public.

According to the World Bank, 40 percent of the debt owed by the world’s poorest

countries is held by China. And attempts by highly indebted borrowers such as

Zambia to restructure their debts to China have been slow and fractured, with

Chinese lenders rarely agreeing to reductions in interest rates or the principal.

Because they are

subject to little public oversight, Beijing’s loans are often diverted for

personal or political gain. A 2019 study in the Journal of Development

Economics found that Chinese lending to African countries increased

closer to elections and that funds disproportionately wound up in the hometowns

of political leaders. These loans skirt local labor and environmental

safeguards and help the Chinese government secure access to natural resources

and strategic assets, boosting state-owned or state-directed enterprises.

Democratic donor

countries and private businesses must increase their investments in projects

that elevate economic and social inclusion and strengthen democratic

norms—decisions that yield more equitable results and stronger development

performance. Together with the rest of the G-7, the United States plans to

mobilize $600 billion in private and public investment by 2027 to finance

global infrastructure. Crucially, we will do so in a way that advances the

needs of partner countries and respects international standards—a model for all

such investments moving forward. This new Partnership for Global Infrastructure

and Investment will finance clean energy projects and climate-resilient

infrastructure; fund the responsible mining of metals and critical minerals,

directing more of the profits to local and indigenous groups; expand access to

clean water and sanitation services that particularly benefit women and the

disadvantaged; and expand secure and open 5G and 6G digital networks so that

countries don’t have to rely on Chinese-built networks that may be susceptible

to surveillance.

Digital Dangers

Like inequality and

economic privation, potentially dangerous digital technologies have not

received nearly enough attention from most democracies. The role such tools

have played in the rise of autocratic governments and ethnonationalism

movements can hardly be overstated. Authoritarian regimes use surveillance

systems and facial recognition software to track and monitor critics,

journalists, and other members of civil society to repress opponents and stifle

protests. They also export this technology abroad; China has provided

surveillance technology to at least 80 countries through its Digital Silk Road

initiative.

Part of the problem

is a lack of global norms and legal or regulatory frameworks that embed

democratic values into tech design and development. Even in democratic

countries, programmers often have to define their professional ethics on the

fly, developing boundaries for powerful technologies while also trying to meet

ambitious quarterly goals that leave them little time to reflect on the human

costs of their products.

Biden came into

office recognizing technology's important role in shaping our future. That is

why his administration partnered with 60 other governments to release the

Declaration for the Future of the Internet, which outlines a shared positive

vision for digital technologies as well as a blueprint for an AI bill

of rights so that artificial intelligence is used in line with democratic

principles and civil liberties. In January 2023, the United States also assumed

the chair of the Freedom Online Coalition, a group of 35 governments committed

to reinvigorating international efforts to advance Internet freedom and counter

the misuse of digital technology.

To build resilience

to digital authoritarianism, we are kicking off a major new digital democracy

initiative that will help partner governments and civil society assess the

threats that misuse of technologies poses to citizens. We launched a new

industry with Australia, Denmark, Norway, and other partners to better align

our export controls with our human rights policies. We blacklisted flagrant

offenders, such as Positive Technologies and NSO Group, both of which sold

hacking tools to authoritarian governments. And in the coming months, the White

House will finalize an executive order barring the U.S. government from using

commercial spyware that poses a security threat or a significant risk of

improper use by a foreign government or person.

But perhaps the

biggest threat to democracy from the digital realm is disinformation and other

forms of information manipulation. Although hate speech and propaganda are not

new, the rise of mobile phones and social media platforms has enabled

disinformation to spread at unprecedented speed and scale, even in remote and relatively

disconnected regions of the world. According to the Oxford Internet Institute,

81 governments have used social media in malign campaigns to spread

disinformation, sometimes in concert with the regimes in Moscow and Beijing.

Both countries have spent vast sums manipulating the information environment to

fit their narratives by disseminating false stories, flooding search engines to

drown out unfavorable results, and attacking and doing their critics.

The most important

step the United States can take to counter foreign influence campaigns and

disinformation is to help our partners promote media and digital literacy,

communicate credibly with their public, and engage in “pre-bunking”—that is,

seeking to inoculate their societies against disinformation before it can

spread. In Indonesia, for example, USAID has worked with

local partners to develop sophisticated online courses and games that help new

social media users identify disinformation and reduce the likelihood of sharing

misleading posts and articles. The United States has also helped Ukraine

fight against the Kremlin’s propaganda and disinformation. For

decades, USAID has worked to enhance the media environment in the

country, encouraging reforms that allow greater access to public information and

supporting the emergence of strong local media organizations, including the

public broadcaster Suspilne. After Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014, our work

expanded to help local journalists produce Russian-language programming that

could reach into Kremlin-occupied territories, such as Dialogues With

Donbas. This YouTube channel featured honest conversations with

Ukrainians about life behind Russian lines. We also helped support the

production of the online comedy show Newspalm, which

regularly racks up tens of thousands of views as it skewers Putin’s lies. And

even before Moscow’s full-scale invasion began in February 2022, we worked with

the government of Ukraine to stand up the Center for Strategic

Communications, which uses memes, well-produced digital videos, and social

media and Telegram posts to poke holes in Kremlin propaganda. Despite

these successes, the global fight against digital authoritarianism remains

fragmented and underfunded. The United States and other democracies must work more closely

with the private sector and civil society groups to identify challenges, build

partnerships, and increase investments in digital freedom worldwide. At the

same time, we must react to new challenges that journalists, election monitors,

and anticorruption advocates face, updating democracy assistance programming to

respond to ever-evolving threats.

To that end, the

United States has launched several new initiatives—many inspired by activists,

civil society, and pro-democracy nongovernmental organizations—under the banner

of the Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal, which Biden unveiled at

his 2021 Summit for Democracy. For instance, we have heard from independent

journalists worldwide that one of the major impediments to their work, in

addition to death threats and intimidation, is lawsuits brought against them by

those whose corruption they seek to expose. These frivolous lawsuits can cost

journalists and their outlets millions, putting some out of business and

creating a chilling effect for others. In addition to helping strengthen the

physical security of news organizations, USAID has established a new

insurance fund, Reporters Shield, that will help investigative journalists and

civil society actors defend themselves against bogus charges. In recognition of

the economic challenges all traditional media outlets face, even in the United

States, we have also organized a new effort to help media organizations that

are struggling financially develop business plans, lower costs, find audiences,

and tap into new sources of revenue so that they do not go bankrupt when

independent journalism is needed most.

The United States is

also working with its partners to support free and fair electoral processes

worldwide. Autocrats no longer simply stuff ballot boxes on election day; they

spend years tilting the playing field through cyber-hacking and voter

suppression. Together, the leading global organizations that support electoral

integrity, both within governments and outside them, have formed the Coalition

for Securing Election Integrity to establish a consistent set of norms for what

constitutes a free and fair election. The coalition will also help identify

critical elections that the United States and other donor countries can help

support and monitor.

A Chinese-built train in Athi River, Kenya

Finally, we are

taking a much more aggressive and expansive approach to fight corruption, going

beyond addressing the symptoms—petty bribes and shady backroom deals—to tackle

the root causes. In late 2021, for instance, the Biden administration announced

the first U.S. strategy on anticorruption, which recognizes corruption as a

national security threat and lays out new ways to tackle it. We are also

working with partner governments to detect and root out corruption occurring

globally, abetted by an industry of shadowy facilitators. In Moldova, for

instance, we helped the country’s electoral commission to encourage greater

transparency in financial disclosures so that external actors looking to exert

influence over elections cannot hide their contributions. And in Bulgaria,

Slovakia, and Slovenia, where USAID had previously closed its missions, we have

restarted assistance to local institutions to support their efforts to curb

corruption.

At the same time, we

are raising the costs of corruption by bringing to light massive multinational

schemes to hide illicit gains. We support global investigative units that unite

forensic accountants and journalists to expose illicit dealings, including

those detailed in the Luxembourg Leaks and the Pandora Papers. And as

corruption grows more complex and global in scope, we are helping link

investigative journalists across borders, including in Latin America,

where such efforts have uncovered the mismanagement of nearly $300 million in

public funding.

Back From The Brink

Democracy is not in decline.

Instead, it is under attack. Under attack from within by forces of division,

ethnonationalism, and repression. And under attack by autocratic governments

and leaders who seek to exploit the inherent vulnerabilities of open societies

by undermining election integrity, weaponizing corruption, and

spreading disinformation to strengthen their grip on power. Worse,

these autocrats increasingly work together, sharing tricks and technologies to

repress their populations at home and weaken democracy abroad.

To fend off this

coordinated assault, the world’s democracies must also work together. That is

why in March 2023, the Biden administration will host its second Democracy

Summit—this time, held simultaneously in Costa Rica, the Netherlands, South

Korea, the United States, and Zambia—where the world’s democracies will take

stock of their efforts and put forward new plans for democratic renewal.

After years of

democratic backsliding, the world’s autocrats are finally on the defensive. But

to seize this moment and swing the pendulum of history back toward democratic

rule, we must break down the wall that separates democratic advocacy from

economic development work and demonstrate that democracies can deliver for

their people. We must also redouble our efforts to counter digital surveillance

and disinformation while upholding freedom of expression. And we must update

the traditional democratic assistance playbook to help our partners respond to

ever more sophisticated campaigns against them. Only then can we beat back

antidemocratic forces and extend the reach of freedom.

For updates click hompage here