By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

India’s Ruling Party Is Losing Control

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is associated with a

network of organizations, often referred to collectively as the Sangh

Parivar (Family of Associations).' In this sense, successfully maintaining a

coalition led by an explicitly religious nationalist political party directly

affects the literature on coalition formation and maintenance.

The Sangh Parivar

includes three frontline groups, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak

Sangh (RSS, National Organisation of

Volunteers), the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP, World Hindu Council), and an

associated student organization called the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP, All India

Student's Council). The Hindu nationalist agenda is also pushed forth by

ancillary organizations not commonly associated

with religious fundamentalist groups, such as labor unions,

think tanks, or rural development organizations. For instance, the Sangh

Parivar includes a very prominent trade union, the Bharatiya

Mazdoor Sangh (BMS, Indian Workers Union), which at times has been active in

voicing its opposition to foreign economic linkages. Likewise, RSS affiliates

such as the Seva Vibhag (SV, Service

Department), the Bharat Vikas Parishad (BVP), and the Vanvasi Kalyan

Ashram (VKA) are nongovernmental organizations that

have been active in working with India's tribal communities. Finally, the

Vidhya Bharati (VB, Indian Enlightenment) is a network of schools. The

Deendayal Research Institute (DRI) has undertaken research work on rural

development.

India’s government is facing a serious conundrum. Its

continued electoral success depends on Hindu majoritarianism, but it must also

maintain stability in the world’s soon-to-be most populous, diverse political

economy. Through Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s

two consecutive terms in office, the ruling Bharatiya

Janata Party (BJP) has energized right-wing Hindu nationalism, which has

undermined social stability in the highly diverse South Asian country. Thus

far, Modi has balanced between the pragmatic needs of governance and

ideological commitment, but this is an untenable situation, especially with

Hindutva having considerably displaced the country's secular character. The

rise of Hindu nationalism endangers regional stability – already at risk due to

a severely weakened Muslim-majority state next door in Pakistan and the return

to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Victims Of Their Success

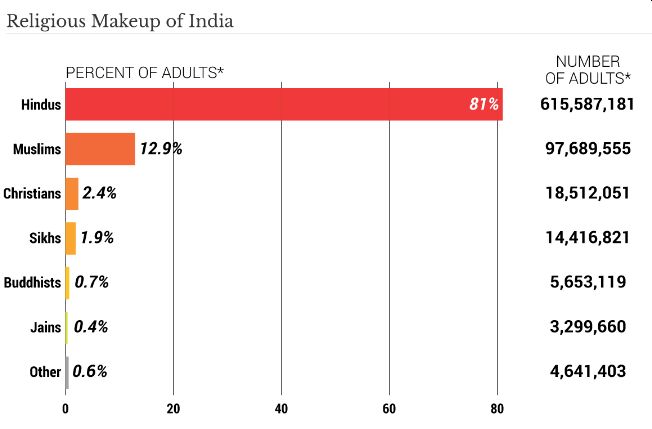

Modi’s BJP has been highly successful at winning

elections, given that Hindus constitute four-fifths of India’s 1.4 billion

people. Retaining power in democratic politics is about much more than

demographic arithmetic. This is particularly the case when almost a quarter of

a billion citizens are not from the majority faith – not to mention the

country’s regional and linguistic differences, especially in the south, where

the BJP’s brand of Hinduism faces resistance. This explains the Modi

administration’s difficult balancing act, amplified by growing domestic unrest,

international concerns, and criticism over the decline of the country’s

long-held secular democratic political tradition.

India’s prime

minister’s annual Independence Day speech reflected

how far political discourse has fallen in New Delhi. PM Modi hereby sported

a Tricolour-themed turban for Independence Day,

imbibing the ‘Har Ghar Tiranga’

spirit. If we look back, one notices that, unlike prior revolutions, India’s

split from the British Empire came about through a political movement committed

to nonviolence. The Indian National Congress, led by Mahatma Gandhi,

organized peaceful demonstrations on an unprecedented scale. The mighty

British Empire ultimately capitulated, encouraging anticolonial movements

worldwide.

The Modi government defused a recent June crisis

involving the BJP’s then-spokeswoman, Nupur Sharma, who made controversial

remarks about the Prophet Muhammad. Sharma’s statements offended many of the

country’s 200 million Muslim minorities and triggered public condemnation from

several Muslim states, including close allies of India. Modi’s BJP was forced

to do damage control, removing Sharma from her position, to prevent the crisis from

undermining its political interests and India’s international standing. In

addition, India's supreme court issued a firm reprimand, saying that Sharma’s

“loose tongue has set the entire country on fire.”

The government’s

efforts somewhat pacified Indian Muslims and Muslim-majority countries, most of

which are close trading partners of India. However, it has triggered a debate

within the BJP’s broader ecosystem known as the “Sangh Parivar,” a

constellation of right-wing Hindu nationalist social and political entities

spawned by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the

parent organization of the BJP. A widespread perception within this community

is that Sharma was unfairly treated for remarks taken out of context and issued

in response to many Muslims’ ongoing mockeries of Hindu deities.

Though the situation was defused, it sheds light on

how the BJP’s ideology can be a liability for the ruling party. The elite of

almost all populist parties of any ideological persuasion is far more pragmatic

than its political base. What leaders say they will do before getting elected

differs from how they behave once in office, where they encounter the

constraints of policymaking and thus need to bridge the gap between campaign

promises and actual policy deliverables. This logic tends to create internal

differences within the ruling political movement where the existing leadership

faces a challenge from far more hawkish elements inhabiting the next echelons.

The BJP is no exception to this rule. The Sharma

incident occurred amid existing tensions between the ideologues within the BJP,

its broader environs, and the party’s top leadership, encumbered by the

imperatives of governing. The BJP’s electoral strategy pushed it toward the

weaponization of Hindutva; the ideology heavily focused on reviving Hindu

civilization by rolling back its Muslim heritage. This strategy created a

conundrum for the BJP because it unleashed majoritarian religious extremism,

which evolved well beyond the BJP’s electoral needs and thus beyond the party’s

control. A prime example of this intra-BJP schism is the state's chief minister

of Uttar Pradesh, Yogi

Adityanath, a hardliner Hindu monk-turned-politician well known for

whipping up anti-Muslim hysteria.

Yogi Adityanath has become the first CM from BJP to

retain power in Uttar Pradesh:

Ideologues like Adityanath, who have been loud voices

for establishing Hindu Rashtra (Hindu State), have been responsible for

mobilizing hundreds of thousands of young militants. To this extremist lot, the

actions of the BJP leadership against Sharma represent, at best, a weak

commitment to their cause and, worse, a betrayal. The move also reinforced the

perception that the project of Hindu Rashtra remains vulnerable to pressures

from Muslim and Islamist actors and that the Indian Muslim minority constitutes

a fifth column within the Indian body politic.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath performs

'Kanya Pujan':

Successor Or Challenger?

The schisms within

the BJP were hardwired into the party’s fabric. Adityanath, for example, is not

originally from the party. Instead, he emerged from a more hawkish strain of

Hindutva in his native Uttar Pradesh through his political vehicle, the Hindu Yuva Vahini, and the highly influential Hindu temple he

leads, known as the Gorakhnath Math. As recently as

the late 2000s, he clashed with the BJP when he fielded candidates against the

ruling party and was instrumental in the defeat of an incumbent finance

minister in the then-BJP government. Seeing his mounting influence in Uttar

Pradesh, the BJP accepted Adityanath as the party leader in the state.

After nearly a decade

as a lawmaker in the Indian parliament, Adityanath returned to state politics

in Uttar Pradesh in 2017 when he became chief minister of the state – a

position he consolidated with his reelection in March 2022. Even before his

second-term victory (the first sitting chief executive of the state to win

reelection since independence), Adityanath emerged as the second most popular

leader in the BJP after its chief, Modi, who has been telegraphing – even if

for political purposes – that the monk is his protege. At 50, Adityanath is

younger than the 72-year-old Indian prime minister. Thus, he has enough time to

position himself as Modi’s successor even though he intends to seek a third

term in the 2024 elections.

Regardless of the future positions of the two men,

Adityanath’s rise has the BJP establishment concerned about the ruling party’s

continued ability to balance between its need to leverage religion to maintain

its unique position in the Indian political landscape and to govern what will

soon be the world’s largest nation. Thus far, the party has been able to do so

by complementing its Hindu First ideology with a powerful political machine

with deep grassroots support and a welfare economic model. But ultimately, the

BJP brand relies heavily on exclusionary politics, which engenders religious

extremism capable of upsetting India’s fragile social stability.

The BJP faces no

effective national-level opponent. Its main rival, the

Congress Party, which ruled the country for 54 of its 75-year history, is a

shell of its former self, given that the BJP’s Hindutva has supplanted its

secular nationalist ideology. However, Hindutva appears to be growing beyond

the ruling party’s ability to harness it for electoral purposes. This long-term

trend will have a direct bearing on India and the stability of the world’s most

densely populated region of South Asia – an area already impacted by Muslim

extremism on its western flank.

For updates click hompage here