By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

The Treacherous Path To A Better Russia

For God’s sake, this man

cannot remain in power,” U.S. President Joe Biden said of his Russian

counterpart, Vladimir Putin, a month after Russia launched a brutal invasion of

Ukraine in February 2022. Biden’s off-the-cuff remark, which his administration

swiftly sought to walk back, did not merely reflect anger at the destruction

unleashed by Putin’s war of choice. It also revealed the deeply held assumption

that relations between Russia and the West cannot improve as long as Putin is

in office. Such a sentiment is widely shared among officials in the

transatlantic alliance and Ukraine, most volubly by Ukrainian President

Volodymyr Zelensky himself, who last September ruled out peace talks until a

new Russian leader is in place.

There is good reason

to be pessimistic about the prospects of Russia’s changing course under Putin.

He has taken his country in a darker, more authoritarian direction, a turn

intensified by the invasion of Ukraine. The wrongful detention of The Wall

Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich in

March and the sentencing of the opposition activist Vladimir Kara-Murza to a 25-year prison term in April, for example, are

eerily reminiscent of measures from Soviet times. Once leaders grow to rely on

repression, they become reluctant to exercise restraint for fear that doing so

could suggest weakness and embolden their critics and challengers. If anything,

Putin is moving Russia more and more toward totalitarianism as he attempts to

mobilize Russian society in support of not just his war on Ukraine and his

antipathy to the West.

If the West’s

relations with Russia are unlikely to change while Putin is in power,

perhaps things could improve if he departs. But the track record of political

transitions that follow the exits of longtime authoritarian leaders offers

little room for optimism. The path to a better Russia is not just narrow—it is

treacherous. Authoritarian leaders rarely lose power while still waging a war

they initiated. As long as the war continues, Putin’s position is more secure,

making positive change less likely. What is more, authoritarian regimes most

often survive in the wake of the departure of longtime leaders such as Putin;

were Putin to die in office or be removed by insiders, the regime would most

likely endure intact. In such a case, the contours of Russian foreign policy

would stay essentially the same, with the Kremlin locked in a protracted

confrontation with the West.

One development,

however, could spark more substantive change in Russia: a Ukrainian victory.

Kyiv’s triumph in the war raises the possibility, even if only slightly, that

Putin could be forced out of office, opening a new style of the Russian

government. A Russian defeat in the war could galvanize the bottom-up pressure

needed to upend Putin’s regime. Such a development carries risks—of violence,

chaos, and even the chance of a more hard-line

government emerging in the Kremlin—but it also opens the possibility of a more

hopeful future for Russia and its relations with its neighbors and the West.

Although fraught, the most likely path to a better Russia now runs through

Ukrainian success.

The Persistence Of Putin

The first barrier to

a post-Putin Russia is, of course, Putin himself. After 23 years in power and

despite the challenges that have mounted since he invaded Ukraine, Putin looks

set to retain control until at least 2036—the end of his constitutional term

limit—perhaps even longer. Since the end of the Cold War, the typical

autocrat who had governed a country for 20 years and was at least 65 years old

(Putin is 70) ended up ruling for about 30 years. When leaders controlled

personalist autocracies—where power is concentrated in the leader rather than

in a party, junta, or royal family—their typical tenure lasted even longer, as

much as 36 years.

Of course, not all

autocrats are so durable; just a quarter of post–Cold War autocrats have ruled

for 20 years or more. Putin’s durability stems from the creation in Russia of

what the political scientist Milan Svolik calls an

“established autocracy,” in which regime officials and political and economic

elites are entirely dependent on the leader and invested in maintaining a

status quo from which they benefit. The longer such established autocrats are

in power, the less likely the regime’s insiders will remove them. A strong

consensus among governing officials about the need to use repression to

maintain stability, as is currently on full display in Putin’s Russia, further

reduces the likelihood that the leader will be removed against his will.

Russia’s war in

Ukraine has done little to change Putin’s outlook. His grip on power has

tightened and will remain strong as long as the fighting continues. Wars

encourage people to rally around the flag, suppressing disagreement and dissent

for national solidarity; polls have shown that Putin’s approval rating shot up

ten points after he launched the invasion. As a wartime president, Putin

has felt empowered to clamp down on critics and quash reporting by independent

media outlets and nongovernmental organizations. Perhaps more important, the

war has better insulated him from potential challengers from within. A

stretched military lacks the bandwidth to mount a coup. The security services

have profited from the war and have little incentive to throw in their lot with

coup plotters. For these reasons, the dynamics created by the war and Putin’s

actions have made him more than less likely to retain power as the battle rages

on, further deferring political change in Russia.

The Tsar Is Dead; Long Live The Tsar

Still, Putin will not

rule forever. There will be a post-Putin Russia at some point, even if it

arrives only after his death. Since the end of the Cold War, 40 percent of

longtime leaders (those rulers in power 20 years or more) of personalist

autocracies have relinquished control by dying. Putin appears set to remain in

office until the bitter end.

The extreme

personalization of the political system, including the absence of a strong

ruling party apparatus in Russia, makes Putin’s passing a potentially perilous

period. The most likely scenario is that power will pass to the prime minister,

Mikhail Mishustin, who would become the acting

president as the formal rules dictate. The upper house of Russia’s parliament

would have two weeks to schedule an election. During that time, the Russian

elite would battle to determine who would replace Putin. The transition process

could be chaotic as key actors vie for power and try to position themselves in

ways that maximize and secure their political influence. The list of regime

insiders that would battle it out is long and includes the likes of former

Russian President Dmitry Medvedev; Sergey Kiriyenko, Putin’s first deputy chief

of staff; and Dmitry Patrushev, Russia’s agriculture minister, whose father,

Nikolai, is the head of the Security Council. Others outside the regime, such

as Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner

mercenary recruitment firm, could add turbulence to the transition. But

ultimately, the fractious elites would most likely converge on a technocrat,

someone in the vein of Mishustin or Moscow Mayor

Sergei Sobyanin, or another seemingly weak consensus candidate whom all players

believe can be controlled and who will preserve the regime that benefits them.

Once the dust

settles, Russia will almost certainly remain

an authoritarian country. Since the end of the Cold War,

authoritarian regimes have outlasted 40 percent of longtime leaders (those

rulers in power 20 years or more) of personalist autocracies that have

relinquished control by dying. Putin appears set to remain in office until the

bitter end.

The extreme

personalization of the political system, including the absence of a strong

ruling party apparatus in Russia, makes Putin’s passing a potentially perilous

period. The most likely scenario is that power will pass to the prime minister,

Mikhail Mishustin, who would become the acting

president as the formal rules dictate. The upper house of Russia’s parliament

would have two weeks to schedule an election. During that time, the Russian

elite would battle to determine who would replace Putin. The transition process

could be chaotic as key actors vie for power and try to position themselves in

ways that maximize and secure their political influence. The list of regime

insiders that would battle it out is long and includes the likes of former Russian

President Dmitry Medvedev; Sergey Kiriyenko, Putin’s first deputy chief of

staff; and Dmitry Patrushev, Russia’s agriculture minister, whose father,

Nikolai, is the head of the Security Council. Others outside the regime, such

as Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner

mercenary recruitment firm, could add turbulence to the transition. But

ultimately, the fractious elites would most likely converge on a technocrat,

someone in the vein of Mishustin or Moscow Mayor

Sergei Sobyanin, or another seemingly weak consensus candidate whom all players

believe can be controlled and who will preserve the regime that benefits them.

Once the dust

settles, Russia will almost certainly remain

an authoritarian country. Since the end of the Cold War,

authoritarian regimes have outlasted 89 percent of the longtime leaders who

died in office. And in every instance in which an authoritarian leader’s death

led to the collapse of his regime, its replacement was also authoritarian. Even

in personalist autocracies, where the question of succession is considerably

fraught, the same regime has survived the leader’s death 83 percent of the

time. Occasionally, an authoritarian leader’s death in office can shift the

political landscape in liberalizing ways, as when Lansana Conté died in Guinea

in 2008, and free and fair elections were held in 2010 for the first time since

that country’s independence. More often, however, an authoritarian leader’s

death in office is a remarkably unremarkable event.

When leaders are

ousted through a coup or unseated in elections, it is safe to assume that some

of the elite and the citizenry have lost faith in them. That disgruntlement

places the regime itself in jeopardy. But when leaders die of natural causes,

no political machinations underlie their demise. The rudiments of the

government remain as they were, and elites have little interest in rocking the

boat. Although they may feud behind closed doors about who should take over the

leadership, they usually get in line behind whichever individual they deem the

safest bet for the regime’s survival.

Were Putin to die in

office, his successor would change little about the Russian regime and its

external relations. Successors who deviate from the status quo invite fierce

resistance from the old guard, who maintains considerable control over the

levers of power in the system. Therefore, new leaders who inherit office from

deceased autocrats tend to adhere to the previous program. When they try to go

off track, demonstrating a tentative interest in liberalizing reform—as

did Bashar al-Assad in Syria and Shavkat Mirziyoyev

in Uzbekistan during their first terms in office—the organs of the state loyal

to their predecessors usually pressure them to revert to more traditionally

repressive practices.

Successors of

deceased autocrats also tend to keep waging their predecessors’ wars even when

such wars are going badly. The political scientist Sarah Croco has found that

successors from within the regime are likely to continue the conflicts they

inherit, given that they would be seen as culpable for a wartime defeat. In

other words, even if Putin’s successor does not share the same wartime aims,

this leader will be concerned that any settlement that looks like defeat would

abruptly bring his tenure to an end. Beyond figuring out how to end the war,

Putin’s successor will be saddled with a long list of vexing problems,

including how to settle the status of illegally annexed territories such

as Crimea, whether to pay Ukraine wartime reparations, and whether to accept

accountability for war crimes committed in Ukraine. As such, should Putin die

in office, Russia’s relations with the United States and Europe will likely

remain complicated, at best.

A Shock To The System

The war has strengthened

Putin’s hold on power, and even his death may not usher in significant change.

At this point, only a seismic shift in the political landscape could set Russia

on a different path. A Ukrainian triumph, however, could precipitate such a

shift. Ukraine's clearest victory would entail restoring its internationally

recognized 1991 borders, including the territory of Crimea that Russia annexed

in 2014. Battlefield realities will make such a comprehensive victory

challenging to accomplish. However, lesser outcomes that see Russia lose parts

of Ukraine that it held before the February 2022 invasion would still send an

unambiguous signal of Putin’s incompetence as a leader, one the Kremlin cannot

readily suppress for domestic audiences. Such outcomes would raise the

prospect, even if only slightly, of Putin’s ouster and a more excellent

reckoning in the Kremlin. The most probable path to political change in Russia

runs through Ukraine.

A Russian defeat will

not easily translate into a change at the top. The personalist nature of

Putin’s regime creates a particularly strong resistance to change. Personalist

dictatorships have few institutional mechanisms to facilitate coordination

among potential challengers, and the elite tends to view their fates as intertwined

with that of the leader; these dynamics help personalist rulers withstand

military losses.

But even personalist

authoritarians are not immune to the fallout of poor military performance. The

political scientists Giacomo Chiozza and H. E. Goemans

find that from 1919 to 2003, just under half of all rulers who lost wars also

lost power shortly after that. As with other seismic events such as economic or

natural disasters, military defeats can expose leaders as incompetent,

shattering their aura of invincibility. Shocks can create a focal point for

mobilization, opening the way for the collective action necessary to dislodge

entrenched authoritarian rulers. In such systems, citizens who want reform

often exist in more significant numbers than assumed but keep their preferences

hidden. Operating frequently in a distorted and unreliable information

environment, they need to learn more about whether others share their views.

This leads to a situation where everyone keeps their heads down, and the

opposition remains private. But a triggering event such as a military defeat

can change calculations, encouraging reformist citizens (even if they are only

a tiny minority) to go public with their positions and leading to a cascade

effect in which more and more citizens do the same. A defeat in the war could

serve as the spark that mobilizes opposition to Putin’s rule.

Crucially, in the

event of a Russian defeat, moves against Putin will likely not come directly

from his inner circle. In personalist systems such as Putin’s Russia, regime

insiders struggle to coordinate a practical challenge to the leader, not least

because the leader seeks to play them off one another. The Russian elite is

split into what the Russian analyst Tatiana Stanovaya

calls the “technocrats,” who are senior bureaucrats, regional governors, and

other implementers of Putin’s policies, and the “patriots,” who are the heads

of the security services, senior officials in Putin’s United Russia party, and

the likes of Prigozhin. These groups hold different

visions for solving Russia’s problems and shaping the country’s future. There

is, therefore, a genuine risk that a move by one group would not be supported

by the other, potentially bringing down the whole system from which they all

benefit. Such dangers create high barriers to any challenge to Putin from the

inside. Even if some elite members wanted to punish Putin for wartime failure,

they would have difficulty mustering a united front.

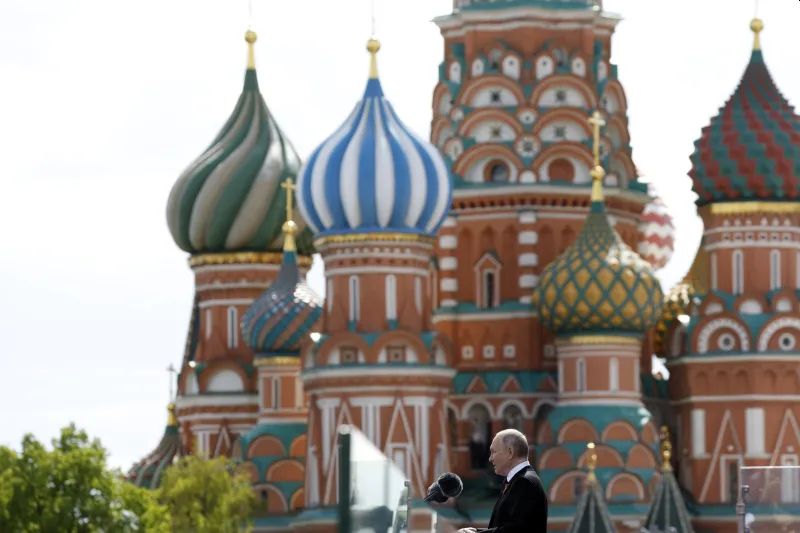

Putin speaking in Moscow, May 2023

Putin has sought to divide

his officials to insulate himself from a coup better. For example, the patriot

camp—comprising Russia’s security services and the most likely origin of an

elite move against Putin—is intentionally segmented into the Federal Guard

Service, the National Guard, and the Federal Security Service, hindering the

unity and coordination necessary for a coup. The absence of a viable

alternative to Putin means no center of gravity around which a challenge could

coalesce. His ability to use the security services to monitor dissent

(including using one service to monitor another) and the high costs of

detecting conflict further lessen the chances of an elite rebellion from

within.

The data confirm that

longtime authoritarian leaders face little risk of coups. Only ten percent have

been ousted in a coup among post–Cold War authoritarian leaders in power for 20

years or more. And, tellingly, no longtime personalist authoritarian leader

over 65 (such as Putin) has been ousted in a coup in this period.

But forces originating

outside the regime could unseat Putin and meaningfully change Russia’s approach

to the world. Given the lack of effective institutions to channel dissent in

today’s Russia, opposition to Putin could spill over, creating a groundswell

that could dislodge him. In fact, in cases where longtime personalist

authoritarian leaders do not die in office, pressure from outside the regime is

the most common way they are pushed out of power. Since the end of the Cold

War, a third of personalist dictators in control for 20 years or more were

toppled by popular protests or armed rebellions.

Putin’s actions since

the invasion raise the possibility of such pressure. Traditionally, autocrats

seek to create an apathetic, demobilized citizenry that they can easily control.

Until the attack, Putin presided over Russia this way. However, since the war

began, he has been forced to announce a “partial mobilization,” calling 300,000

Russians to fight in Ukraine. He has placed Russia on a wartime footing. As the

Russian writer Andrei Kolesnikov has observed, it is no longer possible for

Russians to stay disengaged. “More and more, Russians who are economically

dependent on the state are finding that they have to be active Putinists,” he noted on these pages. Public support for the

regime has become more common, as have incidents in which Russians report on

their fellow citizens' “antipatriotic” activities. But a more mobilized society

could ultimately prove challenging for the regime to control.

Mass Appeal

A bottom-up challenge

to Putin’s rule would create the possibility of political change in Russia but

is not without risks. Pressure from below brings the potential for chaos and

violence should it culminate in an armed rebellion, for example. In Russia,

efforts by ethnic minorities to push for greater sovereignty, as they did after

the fall of the Soviet Union, could further delegitimize Putin and even lead to

his ouster. Several factors work against such centrifugal forces. Putin has

increased his influence over regional leaders by making them more dependent on

Moscow; patriotic pride in the Russian state remains strong in the republics,

and the cause of secession is not especially popular in Russia’s sprawl of

republics. Yet the comparative data suggest it should not be dismissed. The

political scientist Alexander Taaning Grundholm has shown that although the personalization of an

autocracy makes a leaderless vulnerable to internal threats such as coups, it

does so at the expense of raising the risk of civil war. In the post–Cold War

era, 13 percent of longtime personalist leaders were ousted through civil

wars.

Already, Russia’s

regions have borne the brunt of the costs of Putin’s war in Ukraine. The

Kremlin has relied disproportionately on fighters from Russia’s poorest

composed areas of large populations of ethnic minorities, including once

rebellious republics such as Chechnya and provinces such as Buryatia and Tuva.

In Tuva, for instance, one of every 3,300 adults has died fighting in Ukraine.

(The comparable figure for Moscow is one of every 480,000 adults.) In other

regions such as Khabarovsk, people have been disillusioned with Moscow for some

time, as evidenced by antigovernment protests in 2020 after the Kremlin

arrested the region’s popular governor. Another round of mobilization

concentrated in the areas and mounting economic hardship could feed

secessionist sentiment.

A military defeat for

Russia could be the catalyst to set the process in motion. A Ukrainian victory

would signal further weakness in Russia’s central authority and the Russian

military, increasing the likelihood that secessionist groups see the moment as

ripe for taking up arms. The return to Russia’s regions of now veteran fighters

with access to weapons but few economic prospects would further facilitate such

movements. Political entrepreneurs, such as Prigozhin,

may also factor into these dynamics. Prigozhin’s

efforts to upset the power balance in the Putin regime could ignite conflict

between the Wagner paramilitary company and the Russian armed forces and

security services and flare into an outright insurgency.

The Kremlin would

meet any secessionist bids with violence, as it did during Russia’s two wars

with Chechnya. It is impossible to predict whether such moves for independence

could succeed or whether a leadership change at the top, forced by this growing

debacle, could prompt a national reckoning and lead Russians to abjure their

country’s imperialist designs on their neighbors.

What is more

specific, however, is that violent upheaval tends to beget more violence. When

post–Cold War autocrats have been ousted due to civil war, their departures

have virtually guaranteed the establishment of new dictatorships or, even

worse, outright state failure. Examples include the emergence of the Kabila

family’s regime in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) after the

overthrow of Mobutu Sese Soko in 1997 and the

breakdown of the state in Libya after Muammar al-Qaddafi’s ouster in 2011.

Should an armed insurgency unseat Putin, the aftermath would be violent, and

the odds of a new dictatorship coming to power would also be high.

But there is another,

less bloody form of bottom-up pressure that could usher in a more liberal

Russia: widespread protests. Twenty percent of longtime personalist

authoritarian leaders in the post–Cold War era have been ousted by mass

protests. Of course, such a movement faces incredible obstacles in today’s

Russia: high levels of repression, the Kremlin’s dismantling of the opposition,

and the exodus of hundreds of thousands of (often liberal) Russians since the

invasion who might have otherwise taken to the streets. And even if dissenters

could crowd public squares in large numbers, large-scale protests are not

guaranteed to topple Putin, given that authoritarian regimes can generally ride

out such movements. Consider, for example, the experience of Iran this year,

Belarus in 2020 (and in 2010), and Russia itself after controversial elections

in 2011 and 2012. In each case, an authoritarian regime suddenly seemed

vulnerable in the face of mass protests, only to reassert its control, often

violently.

The aftermath of the

mass protests that ousted Hosni Mubarak in Egypt in 2011 and Omar

al-Bashir in Sudan in 2019 reveal that such movements can bring new,

potentially worse, authoritarian regimes to power. The military coup that

toppled the democratically elected leader Mohamed Morsi in Egypt in 2013

illustrates that powerful security apparatuses do not disappear when

authoritarian regimes lose power. Should these actors conclude that democracy

does not suit their interests, they can use force to snuff it out. Even worse,

events in Sudan this year make clear that the security apparatus is often not

unified after the end of personalist rule. Once a strongman is no longer at the

helm, his divide-and-conquer strategies can pave the way for conflict to

explode among different factions. The security forces in Russia are certainly

powerful enough to mount a formidable challenge to any leader who threatens

their interest. And their division into distinct groups increases the chance

that they might come to blows with one another. Successful mass protests are

not, in other words, guaranteed to produce a better Russia.

Nevertheless,

widespread protests provide the most promising path to a more liberal Russia.

Since the end of the Cold War, there have been seven instances in which an

authoritarian leader who had been in power for 20 years or more was unseated

through protests. In three of those—Indonesia in 1998, Tunisia in 2011, and

Burkina Faso in 2014—the countries staged democratic elections within two

years. Those odds may seem low (and young democracies can backslide), but

consider that there are no examples of democratization after the departure of

similar authoritarians who died in office or were overthrown via a coup or

civil war. Other routes to a better, democratic future do not exist. Russians

have the best chance of bringing about a better Russia.

Preparing For A Post-Putin Russia

Putin’s exit will

likely occur with little warning, no matter how he leaves office. His departure

will spur significant debate about how best to approach a post-Putin Russia,

not just within policymaking circles in Washington but within the transatlantic

alliance more broadly. Some allies will view Putin’s demise as an opportunity

to reset relations with Moscow. Others will remain adamant in their view that

Russia is incapable of change. Therefore, The United States must consult allies

about the best approach to a post-Putin Russia to avoid the prospect of his

departure becoming divisive. The alliance's unity will remain critical to

managing relations with a future Russia.

In any scenario, it

will take some effort to discern the intentions of a new Russian leader, even

one who comes to power with the backing of the Russian people. Rather than

seeking to decipher Kremlin intentions—which a new leader will have the

incentive to misrepresent to secure concessions from the West—the United

States and European countries should be prepared to articulate their

conditions for an improved relationship clearly. Such situations should

include, at a minimum, Russia’s complete withdrawal from Ukraine, reparations

for wartime damage, and accountability for its human rights violations. As much

as the United States and European countries will want to stabilize relations

with a post-Putin Russia, Moscow must also be interested in the proposition.

Given the dim

prospects for and the uncertain outcome of any future protests, the expectation

of U.S. and European officials should be that Russia will remain an autocracy

even after Putin departs. Since the end of the Cold War, authoritarianism has

persisted beyond the departure of a longtime autocratic leader in 76 percent of

cases. When such leaders are also older personalist autocrats, authoritarianism

endures (or states fail) 92 percent of the time. Such leaders deeply entrench

authoritarian institutions and practices, casting a long shadow over the

countries they rule.

Managing relations

with Moscow, therefore, requires a long-term and sustainable strategy to

constrain Russia and its ability to wage aggression beyond its borders. Such a

strategy should also aim to weaken the grip of authoritarianism in Russia over

time. Corruption has been a key enabler of the Putin regime; illicit

networks entrench regime interests and prevent individuals outside the

government from gaining influence within the system. To weaken these barriers,

Washington must properly enforce sanctions on the Kremlin’s cronies in the business

world, combat money laundering, make financial and real estate markets in the

United States and Europe more transparent, and support investigative

journalists in their bid to uncover such corruption. The United States can also

bolster Russian civil society, an essential force in forging a more liberal and

democratic country, beginning with supporting the work of the many actors in

Russian civil society—including journalists and members of the opposition—who

have fled the country since the start of the war in February 2022. Backing them

now would help lay the groundwork for a better relationship between the United

States and post-Putin Russia.

However, Washington

and its allies can do little to shape Russia’s political trajectory directly. A

better Russia can be produced only by a clear and stark Ukrainian victory, the

most viable catalyst for a popular challenge to Putin. Such a resounding defeat

is also required to enable Russians to shed their imperialist ambitions and to

teach the country’s future elites a valuable lesson about the limits of

military power. Support for Ukraine—in the form of sustained military

assistance and efforts to anchor the country in the West through membership in

the European Union and NATO—will pave the way for improved relations with a new

Russia. Getting there will be hard. But the more decisive Russia’s defeat in

Ukraine, the more likely it is that Russia will experience profound political

change, one hopes for the better.

For updates click hompage here