By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

Beyond the First World War

It is generally

accepted that the First World War which at the time was seen as a clash of civilizations

and a contest of rival national values still reverberates today. With some

important centennials coming up like (already in the course of 2019 used in the

rhetoric by Prime Minister Viktor Orban) the Treaty of Trianon on 4 June 2020

and (which among others provided for an autonomous Kurdistan) the Treaty of Sèvres on10 August 2020

new complex patterns and alliances were formed many of them who found

themselves at each other’s throats as they struggled with competing claims and

expectations. With some important centennials coming up like (already in the

course of 2019 used in the rhetoric by Prime Minister Viktor Orban) the Treaty

of Trianon on 4 June 2020 and (which among others provided for an autonomous Kurdistan) the Treaty of Sèvres

on 10 August 2020 with the Ottoman Empire, which subsequently as we will see

underneath was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne made on June 24, 1923, with

the new Republic of Turkey. Here many new complex patterns and alliances were

formed many of them who found themselves at each other’s throats as they

struggled with competing claims and expectations including the fact that a

number of centennials will add more to the discussion as to how the war ended.

Not to mention that President Erdoğan seeks revisions in the Treaty of Lausanne

by

2023 due to what he claims to be secret articles signed by Turkish and

British diplomats at a Swiss lakefront resort almost a century ago.

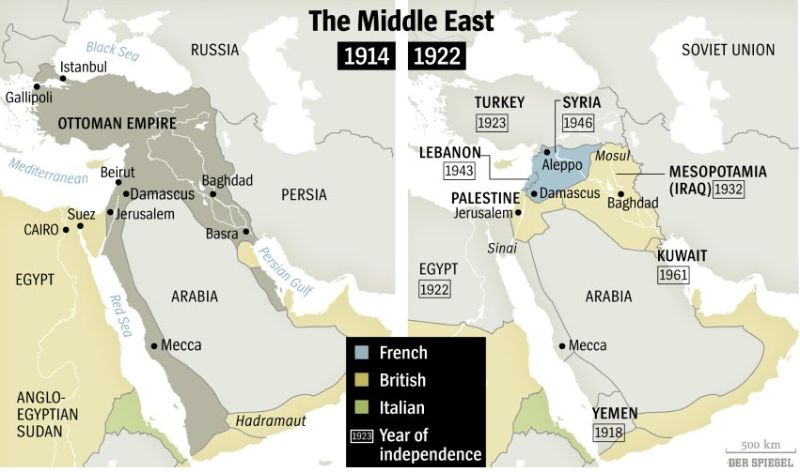

But, as we will see

no region, was more affected or its geography changed as the Middle East. Of

course, in 1914-18 participants in the Middle East had their own reasons for

entering the conflict: the British fought to secure the

Suez canal and the Gulf oilfields; the Turks

feared Russian encroachment and hoped to regain territory lost before the great

war; the Germans sought to destabilize the British empire, the Russians coveted

Istanbul and Anatolia.

Following the rebellion sparked by the Hussein-McMahon

correspondence; the Sykes-Picot agreement; and

memoranda such as the Balfour Declaration the at

first British (closely followed by the French) in

1918 became very influential in the Middle East.

The discussions

between the British and the French who would control what following the break down of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East would reach a fever pitch during the Versailles deliberations.

What is more, as we

will see underneath Turkish pundits today are looking ahead to more serious

foreign-policy challenges, like what will happen in 2023 when the Treaty of

Lausanne expires and Turkey’s modern borders become obsolete. In keeping with

secret articles signed by Turkish and British diplomats at a Swiss lakefront

resort almost a century ago, British troops will reoccupy forts along the

Bosphorus, and the Greek Orthodox patriarch will resurrect a Byzantine

ministate within Istanbul’s city walls...

We know that the First World War was begun with high expectations of

rapid victory. And although many military thinkers feared that a major war

between the Great Powers might prove to be a drawn-out affair, they were

outnumbered by those who believed that offensive tactics would allow for a

swift victory. Instead, the continent was condemned to a drawn-out war of

attrition that ended with the three great empires that dominated Central and

Eastern Europe – Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia – all being destroyed and

replaced by republics. From their peripheral fragments were born the states

that formed complex new patterns and alliances. As has been described, many of

these found themselves at each other’s throats as they struggled with competing

claims and expectations.

The exhausted Western

Powers were in no mood to allow the disputes between the new states of Europe

to erupt into wars that might plunge the continent back into a global conflict.

Although France, Britain, and the United States continued to maintain powerful

navies and the capacity to field large armies, there was no appetite whatsoever

for war, not least because there remained fears that Bolshevism might spread

beyond Russia. The remaining Great Powers were acutely aware that the Russian

Revolution had grown out of Russia’s disastrous performance in the war, and no

nation wished to risk finding itself drawn into a conflict that might end in

the same manner. Instead, the countries of Western Europe all hoped that fear

of future world conflict and the intervention of the new League of Nations

would be sufficient to ensure at least a generation of peace.

Ethnicities and

nationalities had played a large part in the conflict between the three

empires. The spark that ignited Europe – the assassination of Franz Ferdinand

and his wife Sophie – was the result of tensions in

the Balkans, where the Serbs aspired to create a South Slav state under

their control. The entire Austro-Hungarian Empire struggled in vain to keep its

multitudinous nationalities under control, and the lack of any collective sense

of identity or loyalty ensured that it was the first empire where centrifugal

forces combined with war-weariness to create widespread unrest. Nevertheless,

despite these internal pressures and the general expectations that the Dual

Monarchy was an institution with no future, Habsburg rule outlasted that of the

Romanovs in Russia and the Hohenzollerns in Germany.

French

map from the early 1900s, for example, shows the population by ethnicity inside

the Austrian Hungarian Empire:

As Europe settled

down to its new national structures, it was inevitable that many people would find themselves on the wrong side of

the new borders that were often created in haste, or with no regard for the

realities on the ground. Whatever high-minded principles might have led to

Wilson’s insistence on the rights of the peoples of Europe to

self-determination, the fact was far untidier than he might have expected. The

decades of imperial rule had not required different nationalities within any

individual empire to live apart, and while there had been friction between the

different groups, their new status within the modern nations of Europe raised

this to new levels.

The greatest

territorial loser in the rearrangement of Europe was the Austro-Hungarian

Empire, which ceased to exist altogether. The Italians were awarded territories

along their border, completing their long-held dreams of uniting all the lands

that they regarded as Italian; the Balkan parts of the empire were largely

incorporated into the new Yugoslavia; Hungary was forced to concede

Transylvania to Romania; Bohemia and the Carpathian region broke away as the new state of Czechoslovakia; and much of Galicia was

absorbed by Poland. Hungary and Austria became separate states, and in a

remarkably short period, Vienna was changed from the center of a sprawling

empire that stretched from the Swiss border as far as the Ukrainian steppes

into the capital of a relatively small nation in Central Europe. It is a

measure of how inevitable the end of Habsburg rule had seemed for many years

that few Austrians showed any sense of hankering after past glories.

Russia entered the

war under the control of the tsars and ended it under

Bolshevik rule. In absolute terms, its loss of territory – Finland, the

Baltic States, and Poland – was modest, but these regions included some of its

most important economic and industrial centers, particularly Riga. Although exhaustion

brought the series of wars that followed the withdrawal of German forces to an

end, few in the region believed that the Russians had genuinely accepted the

loss of these territories. The Baltic States, in particular, were fearful that

small nations would prove no match for their larger neighbors. Still, it proved

impossible for Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to agree to cooperate militarily

in any meaningful manner. Their vulnerability would be exposed fully in a

future conflict. In the aftermath of the Battle of Warsaw, the Polish Army

managed to seize substantial territory to the east, but this created its

difficulties. Much of the land that now formed eastern Poland had a large non-Polish population, and just as it

was clear that Russia retained ambitions about recovering its Baltic provinces,

there could be no question that, if the opportunity were to arise, the Russian

population of eastern Poland might provide a pretext for the Russians to

attempt to re-enter this region. Piłsudski had hoped that

he might be able to create a Polish-led alliance that would be strong

enough to prevail against both Russia and any future resurgent Germany. Still,

the continuing enmity of the Lithuanians over the status of Vilnius effectively

prevented this from becoming a reality. For the moment, the military and economic

weakness of Germany and the Soviet Union allowed the new states to develop

unhindered, but this was no guarantee of long-term survival. Indeed, the status

of the Vilnius region would be used expertly by the Soviet Union in the manner

in which it absorbed Lithuania.

The former empire

that harbored the highest sense of grievance about the peace that was imposed

upon Europe was Germany. Many Germans felt that their nation had been unfairly

treated in the negotiations that led to the

Treaty of Versailles; they did not accept that Germany was primarily to

blame for the war, and resented the territorial losses that were imposed by the

victorious Western Powers.

Pictured underneath,

opened on 28 June 2019 an exhibition in Arras organized by the Palace of

Versailles starts with the proclamation of the German Empire in the same Hall

of Mirrors that witnessed the Signing of Peace of Versailles on 28 June 1919.

There was an arguable

case for Alsace and Lorraine were returned to French control, but it should be

pointed out that this region was not as unequivocally French as has generally

been stated – by the beginning of the 20th century, less than 12 percent of the population spoke French as

their first language.1 Even at the time of the Franco-Prussian War,

Francophones made up less than half of the overall population. However, the

anger in Germany at the loss of these territories was far less than the

resentment at the French occupation of the Saar region of Germany. The French

had demanded this area as a territorial acquisition during the abortive peace

talks between Vienna and Paris, and there was a considerable concern in Germany

that the French occupation of the Saar might become permanent.

The loss of territory

in the east was also the source of great resentment. Two Baltic cities – Memel,

to the north of East Prussia, and Danzig, to its west – were removed from

German control, even though the majority of their population was unequivocally

German. In both cases, the surrounding countryside was predominantly

non-German, and as has already been described, the Lithuanians took advantage

of this to seize the entire Memelland region and gain

access to the Baltic. The Poles were keen to secure control of Danzig, but

although Woodrow Wilson had assured the Poles that he supported the right of

the new Poland to have a Baltic port, he had likely intended this to be by

union with Lithuania. Instead, Danzig was declared a

free city, and the Poles were given control of a corridor of land running

past Danzig to the coast immediately to the north.

Here, they rapidly developed

the minor port of Gdynia into a new maritime center. The existence of this

corridor resulted in East Prussia is left isolated from the rest of Germany.

This region, undeniably German in its history, culture, and population, had

always been a predominantly agricultural area, and there were constant doubts

that it would be able to survive in its new isolated state without one-day

becoming prey for an expansionist Poland. However, when the southern part of

East Prussia – the Masurian region, where there was

heavy fighting in 1914 and 1915 – was offered a plebiscite in 1920 to decide

whether it would be part of Poland or Germany, the result was overwhelmingly in

favor of the latter. The Poles protested that there had been widespread

intimidation by German police and paramilitary groups, and that results had

been falsified, but it seems that many Poles genuinely preferred to be part of

Germany rather than Poland; the vote took place in July when there was a

genuine threat of Tukhachevsky’s armies reaching Warsaw, and many may have felt

that they would be safer under German control rather than potentially once more

being under the Russian yoke.

All along the eastern

fringes of the new Germany, there were substantial

German-speaking communities in the modern nations of Europe – in Poland,

the Baltic States, the Sudetenland, and Bohemia. Even in Transylvania, there

were tens of thousands of descendants of Saxon settlers who had lived in the

region for hundreds of years. The status of Danzig was unsatisfactory to its

citizens, to Poland, and Germany. Once memories of the terrible cost of the war

began to fade and were no longer strong enough to be offset against the

continued perceived grievances of the Treaty of Versailles, it was almost inevitable

that many in Germany would seek opportunities to put right what they regarded

as abiding injustices. The willingness of a future generation to exploit

grievances both real and imagined made a second all-engulfing war inevitable.

The Austro-Hungarian diplomat Czernin summed up

events with considerable prescience in 1919:

The Council of Four at

Versailles [France, Britain, Italy and the United States] tried for some time

to make the world believe that they possessed the power to rebuild Europe

according to their ideas… That signified, to begin with, four utterly different

purposes, for four different worlds were comprised in Rome, Paris, London and

Washington… Wilson has been scoffed at

and cursed because he deserted his program; indeed, there is not the slightest

similarity between the Fourteen Points and the Peace of Versailles… Clemenceau,

too, the direct opposite of Wilson, was not quite open in his dealings.

Undoubtedly this older man, who now at the close of his life was able to

satisfy his hatred of the Germans of 1870, gloried in the triumph; but, apart

from that, if he had tried to conclude a ‘Wilson peace,’ all the private

citizens of France, great and small, would have risen against him, for they had

been told for the past five years, queues boches

payment tout [‘that the Germans will pay for everything’]. What he did, he

enjoyed doing; but he was forced to do it, or France would have dismissed

him. … And thus there came about what is

now a fact. A dictated peace of the most terrible nature was concluded and a

foundation laid for a continuance of unimaginable disturbances, complications,

and wars… The Entente, who kept up the

blockade for months after the cessation of hostilities, has made Bolshevism a

danger to the world. War is its father, famine its mother, despair its

godfather. The poison of Bolshevism will course in the veins of Europe for many

a long year.

Versailles is not the

end of the war; it is only a phase of it. The fight goes on, though, in another

form. I think possible that the coming generation will not call the high drama

of the last five years the World War, but the World Revolution, which it will

realize began with the World War.2

The closing comments

highlight the widespread preoccupation in Europe with the threat of Bolshevism.

Lenin, Trotsky, and others had always made clear their intent to export their

revolution to the rest of the world, and while the war between Russia and Poland

brought the first, forcible attempt to do this to an abrupt halt, Soviet

doctrine remained unchanged. Even if the threat gradually became more

ideological than the military, the fear of Bolshevism was exploited by those

who wished to play upon the concerns of the ‘bourgeoisie’ who had the most to

lose from the communist government. While the National Socialists in Germany

were amongst the leading exponents of exploiting such fears; they were by no

means alone. Both the Nazis and the Italian fascists demanded antidemocratic

powers as a necessary means of holding back socialism, and such sentiment

spread to non-fascist countries such as the Baltic States and Poland. The

post-war legacy of ethnic minorities on the wrong sides of Europe’s new borders

became intermingled with pre-war thinking about social Darwinism and racial

superiority; not only was it essential to reunite the lost populations with

their homelands, but it was also vital to save them from oppression by races

that were seen as inferior. Even within Bolshevik Russia, there was widespread

prejudice against certain nationalities. After coming to power, Stalin – who

was a Georgian – rapidly implemented a policy of enforcing Russification,

classifying some communities within Russia as ‘enemy nations’. Once assigned

this title, members of these communities – Poles, Germans, Koreans, Chinese,

Kurds, Iranians, Finns, Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians by ethnicity – were

subject to forcible relocation, arbitrary arrest, and even summary execution.3

For many in Germany,

there was an additional factor: the tantalizing sense that German domination of

Eastern Europe almost became a reality after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. While

there was a case for saying that the German Army had been defeated in the west,

it was unarguable that it had prevailed in the east. Also, the soldiers who served with Goltz in Latvia

returned home feeling that they had been promised land in return for their

service; there was a widespread sense of entitlement, which combined with the

notion of German superiority to the Slav people of the region to make many

believe that the Western Powers had cheated

Germany of its rightful gains in the east. If the opportunity arose,

Germany would attempt to make the territorial gains that were snatched away at

the end of the war, not least because

the specter of blockade and starvation had to be avoided in a future conflict;

given British control of the seas, this was possible only if Germany controlled

a vast land-based empire in the east.

Inevitably, many in

Germany attempted to analyze why their mighty army had failed to win the war.

The legend of the invincible army, stabbed in the back by treacherous

politicians and left-wing agitators, was popular with the officer corps in

particular, not least because it absolved them of all blame. Writing many years

later, Hermann Balck gave a somewhat more

sophisticated analysis. There was no question of Germany continuing the war in

the context of the loss of the Romanian

oilfields and the collapse of the k.u.k. Army;

even if Austria-Hungary had been propped up, the vast resources of the United

States would have brought defeat.

Like all the Great

Powers, Germany entered the war with considerable unity and enthusiasm. Still,

as Balck pointed out, this was unlikely to last, and

the political leadership of Germany – the civilian politicians and the kaiser –

did not do enough to ensure that the nation remained united in its pursuit of

victory. Decisions about democratic reforms were postponed until after the

successful conclusion of the war, an error that merely led to disaffection and

growing demands for immediate change. Nevertheless, Balck

also concluded that the German Army was not blameless. The extravagance and

glitter of the early years of Kaiser Wilhelm’s reign alienated many of the

Prussian officer corps, who increasingly turned their backs on politics and

concentrated on purely military matters, a tendency that would cost them dearly

in the Second World War. Balck felt that if Germany

were to win the war, victory had to be achieved in the first years of the war.

Still, despite the constant talk of conflict in the early years of the 20th

century, Germany was ill-prepared for a war that would find it pitched against

multiple opponents. The massive expenditure on the German Navy achieved nothing

other than alienating Britain and diverted precious resources and workforce

from the German Army. Once the war began, there were repeated errors: Balck was particularly critical of Falkenhayn’s strategy,

and felt that Hindenburg and Ludendorff were sidelined for too long.4

Like many reviews

written in the decades that followed, Balck’s opinions are not without merit

but are also selective. There can be no question that the war was lost by early

1918, and there was almost no possibility of the great offensive launched in the

west, bringing about a decisive victory before the immense power of the United

States intervened. But to point out the mistakes that Germany made in the years

before the war and once the conflict began is to ignore similar mistakes made

by Germany’s opponents. While Falkenhayn might have made errors, the commanders

of other armies also miscalculated repeatedly. Ultimately, the war was lost

because Germany and its allies did not have the resources of their

enemies.

The disintegration of

the national sense of unity that took Germany to war was more due to the

enormous pressures placed upon Germany by its enemies than due to negligence by

domestic politicians.

Even in the first

months after the Treaty of Versailles was signed, there were apparent

differences of opinion about whether it had achieved its aims. The British view

was that the destruction of Germany’s fleet had primarily achieved its war

aims. Still, despite Czernin’s condemnation of

Clemenceau, there was considerable dismay in France that the terms were not

harsh enough. The Italians had explicitly entered the war with significant

territorial gains as the price. Although they achieved some of these, others –

particularly the Dalmatian coast – were not granted to them. In the years that

followed, Germany proved incapable of paying reparations on the scale demanded,

leading first to the military occupation of the Ruhr and then to the

cancellation of payments entirely. David Lloyd George, who played a significant

part in the negotiations on behalf of Britain, later wrote an evaluation of the

treaty in which he concluded that it had not removed the military threat

permanently from Germany, and was critical of the manner in which Germany was

treated.5

The issue of

reparations had dominated thinking about the shape of a peace treaty during the

war, not least because of how Germany had imposed reparations on France in

1871. The Germans blamed the collapse of their economy on the punishing

payments that were demanded by the French and Belgians, and whilst it would be

wrong to blame the period of hyper-inflation entirely on reparations, they

certainly contributed to the problems of Germany as it attempted to recover

from the war. John Maynard Keynes, the British economist, criticized the treaty as being fundamentally unfair.

Europe, if she is to

survive her troubles, will need so much magnanimity from America, that she must herself practice it.

It is useless for the Allies, hot from stripping Germany and one another, to

turn for help to the United States to put the states of Europe, including

Germany, on their feet again. If the general election of December 1918 [in

Britain] had been fought on lines of prudent generosity instead of imbecile

greed, how much better the financial prospect for Europe might be.6

Others took a

different view. A leading French economist suggested that by restricting

Germany to a small army, the treaty allowed Germany to divert funding towards

reparations in an affordable manner; others pointed out that the terms were far

more lenient than those that Germany had intended to impose upon its enemies in

the event of a German victory.7

Regardless of whether the financial terms were too severe, it is

difficult to imagine a peace settlement that would have satisfied French and

Belgian demands for reparations and the general desire to weaken Germany militarily, and at the same time

would not have left Germany with a great sense of grievance that could then be

exploited by German politicians for their own ends. In a letter to a friend

written in 1920, Balck mused on the failings of

different parts of German society and made a prophetic statement:

Just like the German Bürgertum [the bourgeoisie], we too, unfortunately, must

strike our Christian religion, at least in its current state, from the list of

factors that can rebuild Germany. The church also has failed. The powerful

force of Christian teachings has been watered down and is heading in the wrong

direction. Our times are screaming for a reformer or a new religion. Socialism

is nothing but the dissatisfaction of the masses on a religious level. 8

For a nation with

little experience of democratic government, it was almost inevitable that

enthusiasm for such new concepts would soon be replaced by disillusionment,

especially in the context of a nation humiliated by defeat and struggling with

worsening financial circumstances. The lure of a strong man with dreams of

reborn nationalism was almost irresistible, and, for a generation brutalized

both at home and in the front line by a terrible conflict, the associated

violence and racism did not raise the concerns and outrage that might otherwise

have prevailed.

It is unarguable that

the roots of the Second World War lay in the imperfect peace that was

established in Europe after the First World War. But such a simple statement

ignores many other factors. Many nationalities were allowed to develop their

states, and Europe was too exhausted to continue fighting until German military

power was unequivocally destroyed – in the absence of such a conclusive defeat,

the terms imposed resulted in perhaps the ‘least worst’ outcome. The world

would have to wait for another war with all its attendant horrors before the

imbalances created in the wake of the First World War were resolved. Still,

while the Second World War settled some issues, it created many more, leaving

Europe divided into two armed camps in a stand-off that would last for over 40

years. While some nations are dragged unwillingly into conflict, those that

enter it in the hope of resolving their problems find that they have merely

exchanged one set of issues for another – and at enormous cost.

In some respects, the

First World War belongs more to the 19th century than the 20th century. It was

a conflict with imperial monarchs, the widespread use of cavalry, and statesmen

who believed that they could arbitrarily redraw the maps of the world. The

events that triggered the outbreak of war show a disastrous failure of

deterrence. Yet, decades later, when Europe was once more armed to the teeth

and divided into two hostile, mutually suspicious camps, deterrence proved to

be effective at preventing war.

Although it was never

as isolationist as some have claimed, the United States turned inward soon

after the Paris Peace Conference. Congress rejected the Treaty of Versailles

and, by extension, the League of Nations. It also failed to ratify the

guarantee given to France that the United Kingdom and the United States would

come to its defense if Germany attacked. Americans became all the more insular

as the calamitous Great Depression hit and their attention focused on their

domestic troubles.

The United States'

withdrawal encouraged the British-already

distracted by troubles brewing in the empire-to renege on their commitment to

the guarantee. France left to itself, attempted to form the new and

quarreling states in Central Europe into an anti-German alliance, but its

attempts turned out to be as ill-fated as the Maginot Line in the west. One

wonders how history might have unfolded if London and Washington, instead of

turning away, had built a transatlantic alliance with a strong security

commitment to France and pushed back against Adolf Hitler's first aggressive

moves while there was still time to stop him.

Perhaps the cultural

memory of the vast waste of the First World War helped the nations of the

world, even if only to a limited extent, from making similar miscalculations

during the nuclear age.

What is more, as we

will see next Turkish pundits today are looking ahead to more serious

foreign-policy challenges, like what will happen in 2023 when the Treaty of

Lausanne expires and Turkey’s modern borders become obsolete. In keeping with

secret articles* signed by Turkish and British diplomats at a Swiss lakefront

resort almost a century ago, British troops will reoccupy forts along the

Bosphorus, and the Greek Orthodox patriarch will resurrect a Byzantine

ministate within Istanbul’s city walls.

As mentioned at the

start, the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, carved the carcass

of the Ottoman Empire into a number of nation-states, including a “Kurdish

State of the Kurds…east of the Euphrates, south of the southern boundary of

Armenia as it may be hereafter determined, and north of the frontier of Turkey

with Syria and Mesopotamia.” It would, said Winston Churchill, Britain’s

minister of colonies, be “a friendly buffer state” between Turks and Arabs.

But the Turks fought

back, making enough trouble that the U.S. supported a new treaty in 1923, the

Treaty of Lausanne. The Treaty of Lausanne allowed the British and French to

carve off present-day Iraq and Syria, respectively, for themselves. But it made

no provision for the Kurds.

The Treaty of Lausanne and the Mosul question

In 1922, Turkish

President Mustafa Kemal Ataturk dispatched his foreign minister, Mustafa Ismet Pasha,

to Lausanne to save the fledgling Turkish republic from the jaws of voracious

European colonialists. Two years earlier, the Treaty of Sevres had dismembered

the Ottoman Empire, ceding big chunks of territory to the leading Allied powers

along with the Greeks, Armenians, and Kurds. Deeply traumatized, Turkey, under

the nationalist command of Ataturk, was determined to return to the negotiating

table, not as a supplicant but as Europe's equal, to re-carve its post-colonial

boundaries in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. Though the country regained control

of Anatolia and the strategic straits through the deal, Turkey left some

critical unfinished business at Lausanne: the former Ottoman vilayet of Mosul.

The Turks demanded

that the British, represented by Foreign Secretary Lord George Nathaniel

Curzon, return the expansive territory, which stretched from Anatolia beyond

the mountains of upper Kurdistan. From there, it followed the Tigris southeast

from the Sinjar Mountains near the Syrian border, across the Nineveh plain

through Mosul to Arbil and Kirkuk before butting up against the Zagros

Mountains along the Iranian border. Ismet Pasha insisted that this swath of

land was the natural dividing line between Anatolia and Mesopotamia, a

strategic frontier where most inhabitants were intricately bound with Turkey by

trade, tongue, and culture. "Mosul has become more closely connected …

with the ports of the Mediterranean than with those of the Persian Gulf,"

he argued. The region's oil wealth, in no small part, influenced the Turks'

interest in Mosul. At the same time, they were also trying to extend the

strategic depth of their new republic as far as possible, knowing that an array

of adversaries could pit ethnic minorities in the Turkish periphery against the

newborn state.

Under the Ottoman

Empire, the Mosul vilayet stretched from Zakho in

southeastern Anatolia down along the Tigris River through Dohuk, Arbil, Alqosh, Kirkuk, Tuz Khormato and Sulaimaniyah before butting up against the western slopes

of the Zagros Mountains, which shape the border with Iran. This stretch of

land, bridging the dry Arab steppes and the fertile mountain valleys in Iraqi

Kurdistan, has been a locus of violence long before the Islamic State arrived.

The area has been home to an evolving mix of Kurds, Arabs, Turkmen, Yazidis, Assyro-Chaldeans, and Jews, while Turkish and Persian

factions and the occasional Western power, whether operating under a flag or a

corporate logo, continue to work in vain to eke out a demographic makeup that

suits their interests.

Lord Curzon, armed

with his own demographic and ethnographic studies, struck down the Turkish

argument at every turn. London could not afford to let the threat of Turkey's

expansionism thwart its own goal of establishing a strategic foothold in

Mesopotamia and monopolizing the region's energy resources. Looking at the

region demographically, Lord Curzon saw the Mosul vilayet as a land full of

Arabs and ethnic minorities who were more willing to fight the Turks than to

assimilate with them. "Why should Mosul city be handed back to the Turks?

It is an Arab town built by Arabs. During centuries of the Turkish occupation

it has never lost its Arab character," he maintained. He also insisted

that the Turkish argument for a natural mountainous buffer along the

Sinjar-Mosul-Arbil-Kirkuk line was disingenuous:

"Ismet Pasha has

suggested that the Jebel Hamrin will make a good defensive boundary. But it is

well known that this is not a great range of mountains, but merely a series of

rolling downs. Is it not obvious that a Turkish army placed at Mosul would have

Baghdad at its mercy, and could cut off the wheat supply almost at a moment's

notice? It could practically reduce Bagdad by starvation."

Ismet Pasha, known

for driving Lord Curzon mad with his penchant for wearing earplugs while his

British counterpart spoke, responded with utmost innocence:

"Turkey, which

has now ceased to be an Empire and become a national State, cannot think of

attacking and conquering a country whose population belongs to a different

race… [T]he Turkish and Arab people who have lived together like brothers for

centuries would obviously never think of attacking each other when left to

themselves."

The Oil Factor

As described by

Martin Gibson, Britain's Quest For Oil: The First World War and the Peace

Conferences, 2017 and Dag Harald Claes, The Politics of Oil: Controlling

Resources, Governing Markets and Creating Political Conflicts, 2018 and Anand Toprani, Oil

and the Great Powers: Britain and Germany, 1914 to 1945, 2019. Oil had little

direct impact on military strategy at the beginning of the war, but that the

lessons of the war made oil important in war aims from 1918 onwards and in

post-war diplomacy. The Allies benefitted from having more oil than the Central

Powers, but their supplies were never secure. Britain's prewar policy of

building up stocks in peacetime and buying on the market in wartime was shown

to be flawed by an oil crisis in 1917. The war showed that Britain had to

control its own supplies in the future; doing so became a post-war aim in 1918.

Britain's power and

prestige were based on its naval supremacy; British dominance of naval fuel

bunkering was a key factor in this. Britain had substantial reserves of coal,

including Welsh steam coal, the best in the world for naval use, but little

oil. Britain's oil strategy in 1914 was to build up reserves cheaply in

peacetime and to buy on the market in wartime. An oil crisis in 1917 showed

that this was flawed and that secure British controlled supplies were needed.

The war created an opportunity for Britain to secure substantial oil reserves

in the Middle East. Attempts to obtain control of these affected the peace

treaties and Britain's post-war relations with its Allies. The USA was then the

world's largest producer and was the main supplier to the Allies during the

war. It believed, wrongly, that its output would decline in the 1920s and

feared that Britain was trying to exclude it from the rest of the world. France

also realized that it needed access to safe and reliable supplies of oil.

The largest available

potential oilfield was in the Mosul vilayet, part of the Ottoman Empire in

1914, and now part of Iraq. The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement allocated about half

of Mosul to France, which in 1918 agreed to include

all of it in the British mandate territory of Iraq in return for a share of the

oil and British support elsewhere. Other disagreements delayed an Anglo-French

oil agreement, but one was finally signed at San Remo in 1920. It was followed

by the Treaty of Sèvres with the Ottoman Empire,

which appeared to give Britain all that it wanted in the Middle East.

The problems with

Faisal becoming King of Irak made Churchill wonder if

it was worthwhile for Britain to stay in Iraq. He told Lloyd-George in

September 1922 that the threat from Turkey meant that extra troops had had to

be kept at Mosul, meaning that expenditure was greater than planned. Problems with

the USA had prevented the development of the oil. He suggested that Britain

should give Faisal an ultimatum that it would leave unless he agreed to

Britain's terms. Whether Britain left entirely or held onto Basra was less

important. Lloyd George wanted to stay, putting Mosul's oil forward as a reason

to do so.

The resurgence of

Turkey under Mustafa Kemal meant that a new treaty had to be negotiated at

Lausanne in 1923. Sèvres angered the USA since it

appeared to exclude US oil companies from Iraq. For a period Britain focused on

the need to have a large British controlled oil company, but it was eventually

realized that control of oil-bearing territory was more important than the

nationality of companies. This allowed US oil companies to be given a stake in

Iraqi oil, improving Anglo-American relations. Britain's need for oil meant

that it had to ensure that the Treaty of Lausanne left Mosul as part of the

British mandate territory of Iraq. Turkey objected, but the League of Nations

ruled in Britain's favor. Britain had other interests in the region, but most

of them did not require control over Mosul. Mosul's oil gave Britain secure

supplies and revenue that made Iraq viable without British subsidies. By 1923

Britain had devised a coherent strategy of ensuring secure supplies of oil by

controlling oil-bearing territory.

The Secret articles of the Treaty of Lausanne myth

At the time of the

British negotiation with the Ottomans over the fate of the Mosul region,

British officers touring the area wrote extensively about the ubiquity of the

Turkish language, noting that "Turkish is spoken all along the high road

in all localities of any importance." This fact formed part of Turkey's

argument that the land should remain under Turkish sovereignty. Even after the

1923 signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, in which Turkey renounced its rights to

Ottoman lands, the Turkish government still held out a claim to the Mosul

region, fearful that the Brits would use Kurdish separatism to further weaken

the Turkish state. Invoking the popular Wilsonian principle of

self-determination, the Turkish government asserted to the League of Nations that

most of the Kurds and Arabs inhabiting the area preferred to be part of Turkey

anyway. The British countered by asserting that their interviews with locals

revealed a prevailing preference to become part of the new British-ruled

Kingdom of Iraq.

As for the above secret

articles signed by Turkish and British diplomats at a Swiss lakefront

resort almost a century ago, British troops will reoccupy forts along the

Bosphorus, and the Greek Orthodox patriarch will resurrect a Byzantine

ministate within Istanbul’s city walls. On the plus side for Turkey, the

country will finally be allowed to tap its vast, previously off-limits oil

reserves and perhaps regain Western Thrace.

Of course, none of

this will actually happen. The Treaty of Lausanne has no secret expiration

clause. But it’s instructive to consider what these conspiracy theories,

trafficked on semi-obscure

websites

and second-rate news

shows, reveal about the deeper realities of Turkish foreign policy,

especially under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s pro-Islam Justice and

Development Party (AKP).

As we have seen above

after defeating the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Britain, France, Italy, and

Greece divided Anatolia, colonizing the territory that is now Turkey. However,

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk reorganized the remnants of the Ottoman army and thwarted

this attempted division through shrewd diplomacy and several years of war.

Subsequently, the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne recognized Ataturk’s victory and

established the borders of modern Turkey. Lausanne then became part of the

country’s foundational myth. For a time it even had its own holiday, Lausanne

Day, when children dressed in costumes representing contested regions of

Anatolia for elementary school plays.

With the Treaty of

Lausanne, so embedded in the Turkish state’s ideology, it is no surprise that

conspiracies about it are ideologically loaded and vary according to the

partisan affiliation of the individual conspiracy-monger. Erdogan’s critics

tend to be more focused on the risks Turkey faces when Lausanne expires.

Conspiracy-minded secularists have always

worried that Erdogan is working with the European Union to establish an

independent Kurdistan or perhaps dig a new Bosphorus to secure American ships’

access to the Black Sea, or really doing anything else possible to undermine

the sovereignty Ataturk secured for Turkey. Some of Erdogan’s supporters, by

contrast, are more optimistic about Lausanne’s expiration, in part based on a

strain of recent historical revisionism suggesting that Ataturk actually could

have gotten a much better deal during the negotiations had he not been in

league with the Europeans — not preserved the whole Ottoman Empire,

necessarily, but at least held on to a bit more of Greek Thrace and maybe the

oil fields of Mosul. Where Ataturk once criticized the Ottoman sultan for

failing to defend Turkish territory in the face of Western aggression,

Islamists have now borrowed this charge for use against Ataturk.

In the realm of

Turkish domestic politics, talk about “the end of Lausanne” reflects the fears

of some and the hopes of others that with former prime minister, now president,

Erdogan’s consolidation of power over the last decade, Turkey has embarked on a

second republic — what Erdogan calls “New

Turkey.” Supporters believe this new incarnation of the Turkish state will

be free of the authoritarianism that defined Ataturk’s republic; critics worry

it will be bereft of Ataturk’s secularism.

Still, the

persistence of the end-of-Lausanne myth shows the extent to which New Turkey

will be indebted to the ideology of the old one. Turkish Islamists have

certainly inherited the conspiratorial nationalism found among many

secularists, complete with the suspicion of Euro-American invasions and

Christian-Zionist plots. (Is it any coincidence Lausanne is in Switzerland, a

center of world Zionism?) While the secularist fringe speculated that Erdogan

was a secret Jew using moderate Islam to weaken Turkey on Israel’s borders,

many in the AKP’s camp now imagine that all Erdogan’s problems are caused by

various international conspiracies seeking to block Turkey’s meteoric rise.

In the realm of foreign

policy, though, these conspiracies belie a deeper truth: Despite the current

violence to Turkey’s south, the borders enshrined in the Treaty of Lausanne are

more secure than they have ever been. And the AKP was the first government to

fully realize this. While Erdogan has often stoked nationalist paranoia for

political gain, as when he claimed foreign powers were behind popular

anti-government protests, the AKP’s foreign policy was the first to reflect a

serious awareness of Turkey’s newfound political and economic power, not to

mention the security that comes with it. Beneath all the bizarre rhetoric and

paranoia, the AKP realized that Turkey has finally moved beyond an era in its

foreign policy defined by the need to defend what was won at Lausanne.

After the Treaty of

Lausanne was signed, Turkey’s main geopolitical aim was the preservation of its

territorial integrity. In the 1920s and 1930s, the threat came from European

powers like fascist Italy. In response, Turkish statesmen embraced perilous neutrality,

controversially staying out of World War II from fear that joining either side

would invite a Russian or German invasion. During the Cold War, the Soviet

Union emerged as a uniquely imminent threat, leading Turkey to abandon its

neutrality and join NATO.

When the Cold War

ended, a new threat to Turkey’s borders emerged: a guerrilla war launched by

the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). This threat helped unite Turkey with Israel

over a shared belief that comfortable Western liberals would never understand why,

in a dangerous neighborhood, killing terrorists, be they Kurdish or

Palestinian, took precedence over human rights. In fact, Turkey entered the

21st century much like Israel: a regional power with a self-perception based on

the fear and insecurity that circumscribed its founding. Amid fevered criticism

of the war in Gaza this summer, it was striking to see a few Turkish

writers offer advice to Israel about the benefits Turkey has found in

overcoming this self-perception.

American observers

often forget that when the AKP came to power in 2003, almost all of Turkey’s

borders, not just the Middle Eastern ones, were potential hot spots. War with

Greece seemed like a real possibility, not to mention with Iran, Syria, Iraq,

or Armenia. Ahmet Davutoglu, then foreign minister, now prime minister, set out

to change this with his signature, if awkwardly translated “zero problems with

neighbors” policy. With the Arab Spring and Syrian uprising having undermined

many of Davutoglu’s accomplishments by creating a host of new problems, it has

been easy to mock this policy for its naiveté. That response ignores the real

benefits the policy delivered to Turkey, particularly on the heels of an era

when Turkey’s fear-driven approach to regional issues sometimes seemed,

instead, like one of “maximum problems with neighbors.”

Among other things,

Davutoglu honed a more diplomatic language appropriate to Turkey’s new power

and ambitions. For example, rather than responding with nationalistic brio to

hostile questions about Turkish claims on the Aegean Sea from Greek sometimes-adversaries,

he would, instead, gently defuse these Balkan bombs by gracefully suggesting

the real question was “how do we make the Aegean a sea of peace?” Turkey,

Davutoglu deftly suggested, had left such petty Balkan disputes behind and had

moved on to more important things. Like making money.

Indeed, sometimes

underneath all the ideological bluster, Erdogan’s government was accused of

being a little too eager to capitalize on Turkey’s new position of economic

strength. Ironically, during the recent war in Gaza, Erdogan’s opponents

criticized his rhetoric toward Israel not as too harsh but as too hollow.

Secular and Islamist critics alike took great joy in pointing

out that while Erdogan has become an outspoken critic of Israel,

Turkish-Israeli trade has nevertheless steadily increased during the AKP’s time

in office, with Erdogan’s son playing a key role. It is a telling sign of the

shift in Turkey that where once the Turkish military worked to maintain good

Turkish-Israeli relations behind the scenes amid public spats, now that role

had been assumed by the Turkish business community.

Ankara was reluctant

to join the West’s anti-Qaddafi coalition in 2011, for example, in large part

because Turkish businessmen had been doing brisk business in Libya to the tune

of almost $10 billion during the previous year. When civil war broke out in Syria

shortly after the uprising in Libya began, Erdogan and Davutoglu were eager to

be on the right side of history from the beginning, and, likely, were also a

little embarrassed that improved ties with Bashar al-Assad’s regime were one of

the most prominent and profitable achievements of the “zero problems” policy.

Now, a stronger,

wealthier Turkey has discovered some of the challenges that a strong, wealthy

country can face. Americans might even recognize a few. The Arab Spring

revealed that undemocratic regimes only make great business partners until they

are overthrown. An exaggerated sense of confidence also led Turkey to take such

an active role in supporting anti-Assad rebels in Syria without fully

considering potential blowback. Turkish voters are now questioning their

country’s role in this violent quagmire, especially after Islamic State

militants, seemingly ungrateful for Turkey’s previous patronage, kidnapped and

held dozens of Turkish citizens working in the country’s consulate in Mosul,

Iraq.

Plus now with renewed

conflicts involving situations like the Syrian

Democratic Forces (SDF) who are led by the Kurdish People's Protection Units

(YPG) and its more recent involvement in Libya foreign policy will be

judged by whether it can continue to translate Turkey’s abstract geopolitical

security, those Lausanne borders still

aren’t going anywhere, into personal safety and stability for Turkish citizens.

In short, Erdogan and will face plenty of challenges even without having to

renegotiate the Treaty of Lausanne.

But all this attests

to the fact that things like the centennial of the Treaty of Trianon on 4 June

2020 (which among others provided for an autonomous Kurdistan) the Treaty of Sèvres on 10 August 2020, or/and the upcoming Treaty of

Lausanne in 2023, which Turkey still believes today that it has " secret

articles" to go in effect in 2023

still have relevance today.

1. Rademacher, M., Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen

1871–1919 (Osnabrück University, 2006) University thesis available online

2. Count Ottokar Czernin (Austrian serving as Foreign Minister from1916 to

1918), In the world war 1920, 2015, pp. 302–305

3. Terry Martin, The

Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union

1923–1939 (Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2001), p. 311

4. Hermann Balck (Author), David T. Zabecki (Editor, Translator),

Order in Chaos: The Memoirs of General of Panzer Troops (2015), pp. 128–133

5. David Lloyd

George, The Truth about the Peace Treaties (Gollancz, London 1938)

6. John Maynard

Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (Harcourt, Brace &

Howe,

New York 1920), pp.

90–91

7. Etienne Mantoux,

Carthaginian Peace, or The Economic Consequences of Mr

Keynes

(Scribner, New York

1952)

8. Balck (2015), p. 137

For updates click homepage here