By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The

consequences of British and French policy in the Middle East

See a list of the personalities connected with British foreign policy towards the Arab

Middle East, 1914–19.

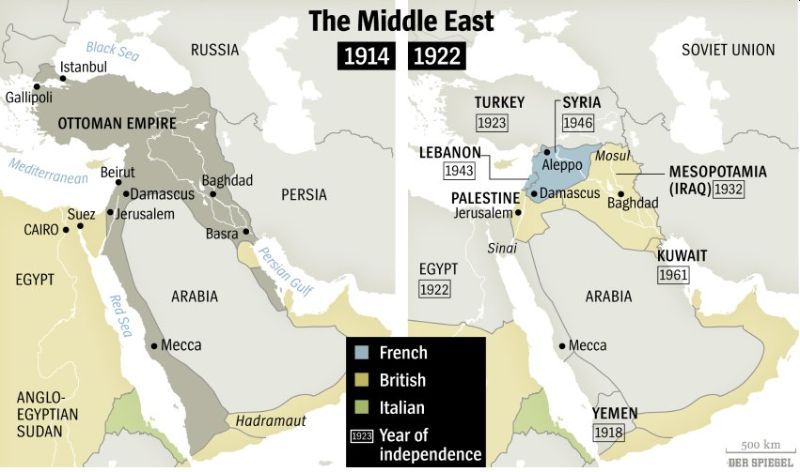

The Middle East played a major role in World War I, and, conversely,

the war was important in shaping the development of the modern Middle East. One

might even say that World War I began and ended with Middle East-related

conflicts.

The modern boundaries of the Middle East emerged from the war. So did

modern Arab nationalist movements and embryonic Islamic movements.

With the onset of WWI, the French and the British sent armies and

agents into the Middle East, to foment revolts in the Arabian Peninsula and to

seize Iraq, Syria, and Palestine. In 1916, French and British diplomats

secretly reached the Sykes-Picot agreement, carving up the Middle East into

spheres of influence for their respective countries. That agreement was

superseded by another which established a mandate system of French and British

control, sanctioned by the new League of Nations

Thus the profound effects

of the British Empire’s actions in the Arab World during the First World War

can be seen echoing throughout the history of the 20th century. The uprising

sparked by the Foreign Office authorizing Sir Henry McMahon to enter into

negotiations with Sherif Hussein and the debates surrounding the Sykes-Picot agreement has

shaped the Middle East into forms that would have been unrecognizable to the

diplomats of the 19th century.

The crux of explaining these events, which now loom so large, is that

Edward Grey and his Foreign Office officials were not very much alive to the

significance of what they were doing because Middle Eastern affairs were not

that important. This meant that as long as Grey and his civil servants

perceived the advice of various experts not to be inconsistent with the essence

of the Foreign Office’s policy – to uphold the Entente with France – they were

prepared to follow it.

This is why they acted without much ado upon recommendations

by Lord Hardinge, Lord Kitchener, Sir Reginald Wingate, McMahon, and

Sir Mark Sykes, even when these contradicted one another. This tendency was

especially prominent during the first months of the war when Cairo was

alternately instructed to encourage the Arab movement in every way possible and

to refrain from giving any encouragement.

The sudden change in the summer of 1915, from a policy of restraint

concerning the Middle East to an active, pro-Arab policy, may also be

explained. Perhaps Wingate and McMahon were able to outstrip the India Office

and the Government of India as the Foreign Office’s premier advisors on the

Arab question because they were, after all, in the service of the Foreign

Office, perhaps because Austen Chamberlain had succeeded Lord Crewe as

secretary of state for India. Still, the main point is that Sir Edward and his

officials need not have had ‘good’ reasons for thinking that Wingate and

McMahon were in a better position to judge how to react to Hussein’s opening

bid. Wingate’s letters and memoranda played a role in the Foreign Office’s

conversion to a more active, pro-Arab policy. Still, it is highly improbable

that Grey and his officials would have been receptive to Sir Reginald’s

arguments if they had invested heavily in the restraint procedure advocated by

the Indian authorities.

The negotiations that led to the signing of the Sykes-Picot agreement

presented more of a technical problem than a politically sensitive one to the

Foreign Office. Once it was realized that the conflicting claims of Arabs and

French regarding Syria were amendable to a settlement – as Wingate, Sir John

Maxwell, McMahon, Aubrey Herbert, and Sykes, one after the other, had

emphasized – the Arab question became something of a routine affair, something

that was covered by the rule that nothing should be done that might arouse

France’s Syrian susceptibilities. The negotiations with the Emir of Mecca could only be concluded after those with

the French had successfully been completed. Even though the authorities in

Cairo and Sykes urged the vital importance of a quick reply to Hussein’s

overtures, the negotiations with the French, as these entailed consultations

with the relevant departments and Russia, had to run their course. This also

implied that it was tough to stop these negotiations once we were underway.

Neither the information that the Arabs were in no position to rise against the

Turks (which seemed to have knocked the bottom out from under the raison d’être

of the negotiations) nor that Hussein was not the spokesman of the Arabs (which

appeared to imply that, perhaps as far as the Arab side was concerned, there

was nobody to negotiate with) halted their progress. Regarding the relative

importance of the Arab question, it is naturally also very telling that, after

the Anglo-French agreement had been signed in the middle of May 1916, nobody in

the Foreign Office observed that the way was now clear to finalize the

negotiations with the Emir of Mecca, or noticed, at the beginning of June, that

he had started his revolt before the talks with him had been completed.

For British policymakers, the sending of British troops to Rabegh was unquestionably an important question as far

as the Middle East was concerned during the years of the Asquith governments.

They were very much alive to the significance of this question, now wholly

forgotten. Some ministers, notably Lord George Curzon, Chamberlain, Grey,

Arthur Balfour, and David Lloyd George, dissatisfied with how the war was being

conducted, believed that Rabegh provided

the opportunity to challenge the dominant view that the war could only be won

in France and that sideshows must be avoided at all costs. Although the

significance of the Rabegh question was

largely symbolic − a small ally, a small force − the stakes regarding

credibility were very high due to Sir William Robertson’s initial flat refusal

even to consider the dispatch of troops. This implied that the protagonists in

this controversy were reluctant to put their credibility at risk. That is why

the War Committee’s policy on Rabegh amounted

to the decision to postpone the decision, even when it had been decided to make

a decision. Of course, this also applies to Wingate, the strongest advocate of

sending troops.

Another major event with far-reaching consequences for the present-day

Middle East is the private deal between Lloyd George and French Prime Minister

Georges Clemenceau on 1 December 1918, which brought Palestine and Mosul

into the British sphere. In 1919, Lloyd George made several attempts to get

Clemenceau to accept another revision in Britain’s favor of the boundaries in

the Sykes-Picot agreement. Clemenceau greatly resented these, given his

concessions in December, and started openly to accuse Lloyd George of bad

faith. This resulted in the settlement of the Arabic-speaking parts of the

Ottoman Empire turning into a highly personal affair between the two prime

ministers. The credibility stakes became higher and higher. By the autumn of

1919, only the two prime ministers were still prepared to let the Middle East

further burden Anglo-French relations. In the end, Lloyd George gave in as far as the south-eastern border

of Syria was concerned and had more or less his way regarding the northern edge

of Palestine, but this only after Clemenceau had left office.

As the British decision-making on the Arab question 1914–19 is

concerned, noticeable is the rapid decline of the Foreign Office’s influence,

which set in after Balfour had succeeded Grey. During the first years of World

War I, British Middle East policy was very much the Foreign Office’s preserve.

With the support of Prime Minister Henry Asquith, Grey was eager to guard the

Foreign Office’s preeminence. Moreover, after 11 years as foreign secretary,

the Foreign Office had to a considerable extent, become ‘his’ department, so

that Grey and his officials most of the time spoke with one voice. This was

altered drastically after the advent of the Lloyd George government in December

1916. Compared to Grey, Balfour could only be an outsider and continued to be so

during his tenure at the Foreign Office. His reputation was not bound up with

the department, and he ran the office in much the same lackadaisical manner as

he had run the Admiralty. This left Lloyd George ample space to intervene in

British Middle East policy and bypass the Foreign Office whenever he felt like

it. The first occasion was the conference of St Jean- de-Maurienne in

April 1917 to settle Italian claims in the Eastern Mediterranean, where no

representative of the Foreign Office was present. The frequency of Lloyd

George’s interventions increased over time. In 1919, as far as the settlement

of the Syrian question was concerned, the Prime Minister was utterly in

command, and the Foreign Office could only follow.

When he was chairman of the Eastern Committee, Curzon succeeded in

curbing the Foreign Office’s grip on Middle East policy, which Lord Robert

Cecil greatly resented. Still, when Curzon became acting foreign secretary in

January 1919, it soon became apparent that he lacked the power to reverse the

tide and reestablish the Foreign Office’s authority in this policy area. I

cannot imagine a better illustration of just how low the Foreign Office’s

reputation had sunk by the autumn of 1919 than Curzon having to request Lloyd

George that he be present at the negotiations with Faisal.

The eclipse of the Foreign Office also implied that the basis of its

policy towards the Middle East – that nothing must be done that might excite

French susceptibilities concerning Syria – was gradually eroded from 1917

onwards, with the result that in 1919 Lloyd George, confident that he could

dictate terms to the French, had no qualms in treating these with contempt.

Where traditional Foreign Office policy implied that possible trouble in the

Middle East was preferred over the problem with the French, Lloyd George’s

priorities were precisely the opposite. In this connection, one should not fail

to point out the policy advocated by Cecil in 1918. However, at first glance,

it might have looked like a return to the Foreign Office’s traditional

approach, actually was nothing of the kind. It wasn’t very friendly to French

interests as Lloyd George’s. Although Cecil accepted that Britain’s signature

of the Sykes-Picot agreement held good, at the same time, he tried to undermine

the French position by creating facts on the ground, trying to bind the French

to the principle of self-determination and induce the Americans to step in and

force the French to recognize that the agreement was inconsistent with the

spirit of the times. Where Lloyd George was blunt, Lord Robert was too clever

by half, and both failed in their attempts to get the French to give up their

acquired rights in Syria under the Sykes-Picot agreement.

Whenever ‘the men on the spot’ did not see eye to eye with the

decision-makers in London, the former did not succeed in convincing the latter

that the policy they advocated should be abandoned and a different one adopted.

Although officials, soldiers, and ministers in London readily accepted that

their knowledge of Middle Eastern affairs was inferior to that of those who

were there (except Curzon and Sykes, of course), at the same time, they did not

doubt that their knowledge was superior, because they saw the bigger picture,

however vague that picture might be. This equally applied to the Foreign

Office’s traditional policy that nothing should be done that might arouse

French susceptibilities concerning Syria and to Balfour’s policy to create

in Palestine the conditions that would give the Zionists the opportunity to establish a Jewish

state (provided that the rights of the existing population were

respected). Concrete, practical difficulties did not stand a chance against

lofty principles and general notions. At best, such challenges were

acknowledged in London while the men on the spot were encouraged to bear with

them. At worst, these were merely seen as attempts by the latter to obstruct

agreed policy and yet to have it their way. The insensitivity of the London

decision-makers to the worries and warnings of the British authorities in the Middle

East triggered the latter to

depict the consequences of their policy proposals were not adopted in the

shrillest terms.

Disaster would surely follow if the demands of the Arab nationalists

were not met right away, if a brigade was not sent to Rabegh if

the British government insisted on implementing the Balfour Declaration.

However, that same insensitivity also had the result that when these dire

consequences failed to materialize, hardly anybody in London noticed this and

called to account those who had uttered these empty threats. Sykes’s temporary

prominence in British Middle East policy was not the result of his testimony

before the War Committee after he toured the Near and Middle East but of his

success in coming to a speedy agreement with François Georges-Picot. From May

1915 onwards, Curzon was the (War) Cabinet’s expert on Middle Eastern affairs

in residence, so to speak, and although he sometimes managed to thwart the

policy initiatives of others, especially Sykes’s, he never managed to put his

stamp on the main lines of British Middle East policy. On the contrary, even

though he knew next to nothing about the Middle East, Lloyd George certainly

did.

For updates click hompage here