By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

For reference, see a list of the personalities connected with British foreign policy towards the Arab

Middle East, 1914–19.

As we have seen yesterday in

the war of 1914-18, participants in the Middle East had their reasons for

entering the conflict, and for the British, the focus was to secure the Suez Canal and the Gulf oilfields.

The actions in the Arab World during the First World War can be seen echoing

throughout the history of the 20th century. The uprising sparked by the Foreign

Office authorizing Sir Henry McMahon to enter into negotiations

with Sherif Hussein and the debates surrounding the Sykes-Picot agreement has shaped the Middle

East into forms that would have been unrecognizable to the diplomats of the

19th century.

Following the Arab revolt sparked by the Hussein-McMahon correspondence; and

memoranda such as the Balfour

Declaration, the first British (closely followed by the French) 1918 became very

influential in the Middle East.

They acted without much ado upon recommendations by Lord Hardinge,

Lord Kitchener, Sir Reginald Wingate, McMahon, and Sir Mark Sykes, even when

these contradicted one another. This tendency was especially prominent during

the first months of the war when Cairo was alternately instructed to encourage

the Arab movement in every way possible and to refrain from giving any

encouragement.

The negotiations with the Emir of Mecca could only be concluded after those

with the French had successfully been completed. Even though the

authorities in Cairo and Sykes urged the vital importance of a quick reply to

Hussein’s overtures, the negotiations with the French, as these entailed

consultations with the relevant departments and Russia, had to run their

course.

The revolt was officially initiated at Mecca on 10 June 1916, the aim

of the revolt was to create a single unified and independent Arab state

stretching from Aleppo in Syria to Aden in Yemen, which the British had

promised to recognize.

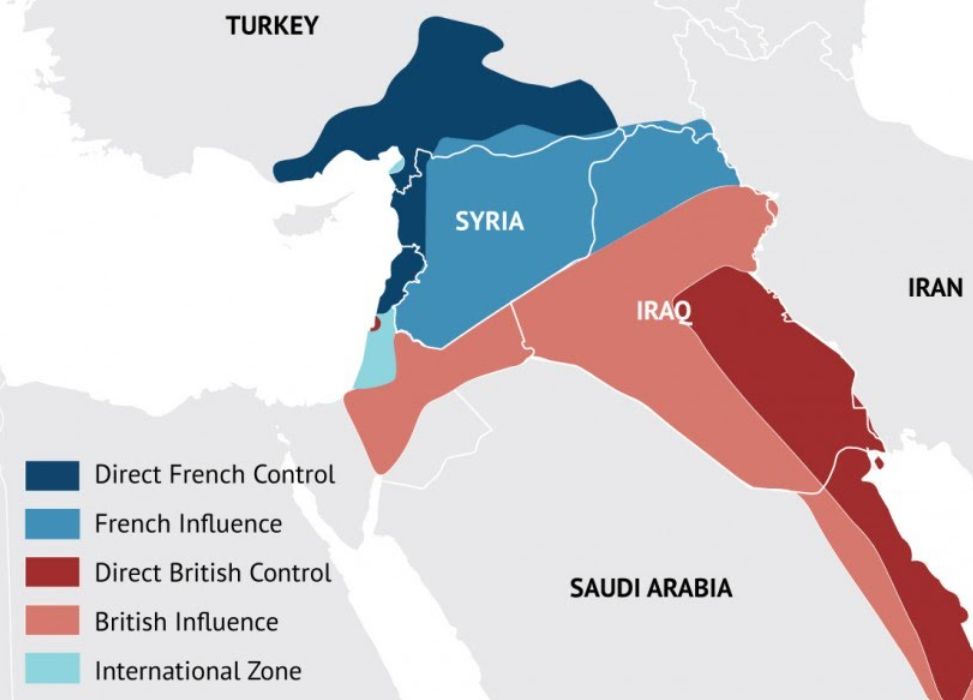

The discussions between the British and the French about who would

control what following the breakdown of the Ottoman Empire in the

Middle East would reach fever

pitch during the Versailles deliberations.

During the Paris peace conference, Augustus John painted a portrait of

T.E. Lawrence, dressed in Arab robes, including a dagger. It resonated with the

British public. According to Christine Riding, it distilled a Western

orientalist desire for power over the Orient while suggesting that that power

in the figure of Lawrence would be exerted with ‘knowledge, understanding and

empathy’.1.

By the time Faisal himself arrived in Paris on February 6, 1919, to

present the case for Arab ‘self-government’ in Syria, Lawrence and the British

had assembled an entire public relations team for him, pumping gullible

journalists (especially American ones) with tales of derring-do by the

Hashemite prince. Embracing his part, Faisal showed up to address the Supreme

Council wearing ‘white robes embroidered with gold,’ with ’a scimitar at his

side,’ thus inaugurating the curious twentieth-century tradition of Arab

leaders addressing diplomatic assemblies while fully armed. In an inspired

touch, Lawrence ‘interpreted’ Faisal’s remarks to the Supreme Allied Council

himself (in fact, Lawrence’s Arabic was relatively poor, so what he was doing

was making Faisal’s arguments for him). Speaking for Faisal, Lawrence said that

the Arabs wanted, above all, self-determination. The Lawrence-Faisal promotion,

judging by the effusions of Colonel House (in whom Faisal ‘inspired a kindly

feeling for the Arabs’) and U.S. secretary of state Robert Lansing (Faisal

‘seemed to breathe the perfume of frankincense’), thoroughly bamboozled the

Americans. The French, outmaneuvered, denounced the infuriating Faisal as ‘British imperialism with Arab

headgear.’ 2

Below is the Arabian Commission to the Peace Conference at Versailles

and its advisors.

Fear of French dominance and the need to establish an alliance that

would support his political ambitions led Faisal to initiate the United States’

Middle East initiative. The inquiry was, in part, a result of the Hashemite

prince’s choice not to reject the fresh mandates system outright while in Paris

- a decision that immediately generated much controversy within nascent

nationalist circles across bilad al-sham,

or Greater Syria.3

Lloyd George and the British believed that, in Faisal and his Arab

irregulars, they had an ace in the hole, a façade to rule behind.

Anticipating this very

track, the French press sought to undermine Faisal’s Arabs by playing

Lawrence’s role in leading them. In light of his later rise to world fame,

Lawrence was entirely unknown to the Western public before the end of the war,

largely by design. Both Allenby and his chief political officer, Gilbert

Clayton, had concealed Lawrence’s role in public communiqués so as not to

compromise Faisal’s political prospects. As late as December 30, 1918, Lawrence

was unmentioned in the account of the fall of Damascus published in the London

Gazette. 4 It was a French newspaper that first broke Lawrence’s ‘cover,’

expressly to belittle Faisal’s Arabs. Colonel Lawrence, the Echo de Paris

reported in late September 1918, riding at the head of a cavalry force of

‘Bedouins and Druze,’ had ‘sever [ed] enemy communications between Damascus and

Haifa by cutting the Hejaz railway near Deraa,’ thereby playing a part of the

most significant importance in the Palestine victory.’ 5

By introducing T. E. Lawrence to the world, the French scored their own

goal of the most self-destructive kind. Seeking to undermine Faisal, the Echo

de Paris had instead glorified Faisal’s greatest champion, a man born for the

role of mythmaker. Rather than deny his role in the Arab revolt, Lawrence

shrewdly manipulated his newfound fame, presenting himself not as an effective

liaison officer who had helped Arab guerrillas blow up some railway junctions

but as a witness to an Arab national awakening.6

At a meeting of the Cabinet’s Eastern Committee in December 1918, Edwin

Montagu, Secretary of State for India, complained of drifting into a position’

Right from the east to the west there is only one possible solution to all our

difficulties, namely that Great Britain should accept responsibility for all

countries. 3 Whereby Churchill believed East and West Africa offered better

opportunities for imperial development than the Middle East.7

Or, as an adviser to the British delegation to the Versailles peace

conference also overheard Prime Minister Lloyd George musing aloud:

‘Mesopotamia … yes … oil … irrigation … we must have Mesopotamia; Palestine …

yes … the Holy Land … Zionism … we must have Palestine; Syria … h’m… what is

there in Syria? Let the French have that.’ 8 Other ministers sought to exploit

the opportunity created by Turkey’s defeat and Russia’s implosion to ensure

against a recrudescence of the latter’s power and strengthen India’s forward

defenses.

However, outlining his Fourteen Points in January 1918, Wilson

declared:

There was to be a free,

open-minded, and impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a

strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of

sovereignty, the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight

with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined. As

to the Ottoman Empire, the non-Turkish peoples ‘should be assured an undoubted

security of life and an unmolested opportunity for autonomous development.9

Although Wilson proved unable to impose his ideas on his European

allies, he had struck a powerful international chord. Even Mark Sykes acknowledged in March 1918 that

the world had moved on since his agreement with Picot, which could now ‘only be

considered a reactionary measure.’ 10

In November 1919, the British and French felt it necessary to declare

publicly that the end for which the two countries had prosecuted the War had

been ‘the complete and definitive liberation of the peoples long oppressed by

the Turks and the establishment of national governments and administrations

drawing their authority from the initiative and free choice of the indigenous

populations.11 This was not, as events proved, to be taken at face value, not

least because part of the British motive in issuing the declaration had been to

undermine French claims to Syria. In Curzon’s words;

If we cannot get out of our difficulties in any other way, we ought to

play self-determination for all it is worth wherever we are involved in

problems with the French, the Arabs, or anybody else and leave the case to be

settled by that final argument, knowing in the bottom of our hearts that we are

more likely to benefit from it than is anybody else.12

Wilson’s primary influence next was reflected in the new concept of

League of Nations mandates. To many, they were simply a means of draping the

crudity of conquest in a veil of morality. That was the view indeed in Baghdad,

where in June 1922, Al-Istiqlal declared that ‘we do not reject the

mandate because of its name but because its meaning is destructive of

independence.’ 13 Nevertheless, mandatory powers were accountable for their

administrations of the new territories to the League of Nations. Category A

mandates, which included those for the Middle East, were for countries nearly

ready to run their affairs. The prospect of independence, in other words, was

explicitly recognized, with the power of the mandatory being only

temporary.14

Much would depend on the development of Arab nationalism. This could

only be exacerbated by the imposition of British hegemony in the place of an

Ottoman Empire, which had excited relatively little opposition and had at least

the advantage of being Muslim.15 The time had gone, as Major Hubert Young at

the Foreign Office noted in 1920;

when an Oriental people will be content to be nursed into

self-government by a European Power. The spread of Western education increased

communication facilities. Above all, the War, with the resultant emergence of

the Wilsonian principle of self-determination, has combined with bred in the

minds of Eastern agitators a distrust for, and impatience of, Western control.

We cannot ignore this universal phenomenon without endangering and possibly

losing, beyond possible recall, our position in the East.

The problem was not, in

Young’s condescending view, insoluble, so long as Britain was careful to,

distinguish between the wild cries of the extremist, anxious to secure for

himself and deny to the foreigner what he regards as the spoils of government,

and the childish vanity of the masses on which he brings his armory to bear. If

we could but descend to tickling that vanity ourselves, we should deprive the

agitator of his most potent weapon.16

Young’s solution, which was to work for the next two decades, was the

recognition of native governments and then entering into a treaty relationship

with them.

There were two more immediate constraints on British policy. The

disadvantages of some of the wartime agreements were becoming apparent. British

ministers and officials believed that they had conceded too much to the French.

In the opinion of the General Staff, it was difficult to see how any

arrangement ‘could be more objectionable from the military point of view than

the Sykes-Picot agreement […] by which an enterprising and ambitious foreign

power [i.e., France] is placed on interior lines concerning our position in the

Middle East.14 There was talk of confining the French to the narrowest possible

limit of Arab land, preferably in the region of Beirut. At the same time, there

was a belated appreciation of the contradictions between the various British promises

as they affected Syria and Palestine and the Zionists and Palestinians.18

The other pressing constraint was military overstretch. In 1918 British

power in the Middle East was at its apogee. More than a million British and

imperial troops now occupied the Ottoman Empire. 19 Forces on this scale could

not be sustained for any time. However, the rapid demobilization of 1919

occurred against a background of emergencies across the world, stretching from

India, via Egypt and Turkey, to Ireland, all of which were tying up British

troops. The press, led by Lord Northcliffe’s Times and Daily Mail, believed

they had found a useful stick to beat Lloyd George. A Times editorial of 18

July 1921 complained that while nearly £ 150 million had been spent since the

Armistice on ‘semi-nomads in Mesopotamia,’ the government could only find £

200,000 a year for the regeneration of British slums and had to forbid all

expenditure under the 1918 Education Act. 20

If these weren’t handicaps enough, the continued division of

responsibility for the region between government departments was now further

exacerbated by the division of government between London and the peacemakers in

Paris. This made for endless discussion without resolution. Nor did it help

that Lloyd George had a habit of acting without reference to his advisers,

departments, or prepared positions. 21

The Middle East was but one of many immensely complex problems facing

the peacemakers. The broad outline of the settlement in the Middle East was not

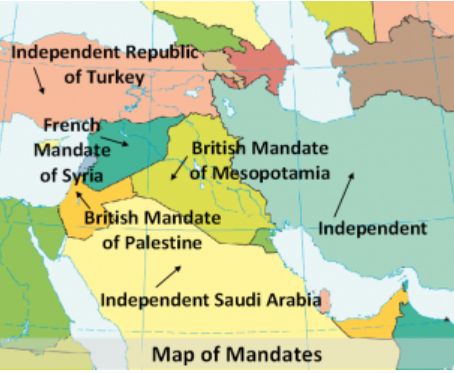

evident until the San Remo conference of April 1920. Here the British and

French effectively awarded themselves mandates over Iraq (as Mesopotamia now

came to be known), Palestine, and Syria. As Curzon told the House of Lords, the

gift of mandates lay not with the League but ‘with the powers who have

conquered the territories, which it then falls on them to distribute.’ 22 It

was only at a conference of British officials and experts held in Cairo in

March 1921 and chaired by the Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, that the

question of rulers was decided, with the award of the Iraqi and Transjordanian

Thrones to two of the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein ibn Ali of the

Hashemite family’s sons, Abdullah and Faisal.

Although British policymakers saw linkages between the various

ex-Ottoman territories, there was little way of an overview of policy towards

the region. The outcomes are best understood on a country-by-country basis.

Thus Faisal and the French were immediately at odds over Syria. At issue was

not simply a territorial dispute between two rival claimants but the first

political contest between a European imperial power and a claimant standing on

the rights of self-determination. As Faisal told Lloyd George, he ‘could not

stand before the Muslim world and say that he had been asked to wage war

against the Caliph of the Muslims and now see the European powers divide the

Arab country.’ 32

With Woodrow Wilson reluctant or unable to turn his stirring rhetorical

support for self-determination into political reality, Faisal was almost

totally dependent on the British. Having committed themselves to both sides,

they equivocated and wriggled. The French prime minister,

Georges Clémenceau, who was primarily concerned with security against

Germany, had little interest in the empire. In December 1918, he had been

willing to agree to British control of Palestine and Mosul, the latter with the

critical proviso that French companies would have a share of oil rights there.

But he assumed that Damascus and Aleppo would be his quid pro quo. Syria was

one question he could not politically afford to concede. Vital Catholic

interests were determined to ensure that France retained its historic

‘presence’ in the Middle East. At the same time, the War had demonstrated

France’s vital interest in the empire for manpower, money, and raw materials.

‘No other nation other than France’, wrote Maurice Barres in the Echo de Paris,

in a comment which would certainly not have been approved by any official

English reader, ‘possesses in so high a degree the particular kind of

friendship and genius which is required to deal with the Arabs […] If England

wishes to give a kingdom to this Amir, let him set up in Baghdad.’ 33

Lloyd George nevertheless seemed determined to try to deny the French

their one Middle Eastern prize. His military advisers wanted a railway link

between Palestine and Iraq across Syrian territory for imperial communications.

Allenby warned of the risk that a French mandate would lead to a war between

France and the Arabs. Besides, the Prime Minister admired Faisal and believed

that he had been promised at least the interior of Syria and that French rule

would be more oppressive than British rule in Palestine and Iraq. For much of

1919, therefore, the British tried either to reconcile the two parties or get

the French to change policy and even withdraw. This led to some furious

exchanges between Clémenceau and Lloyd George. On one of these occasions, Clémenceau accused

Lloyd George of being a cheat. 34

In the face of French intransigence, the British opted for France by

autumn. They could no longer afford to keep an army of occupation in Syria.

Moreover, as Sir Arthur Hirtzel, Permanent Under-Secretary in the India

Office, put it, ‘If we support the Arabs in this matter, we incur the ill-will

of France; and we have to live and work with France all over the world.’ 35

British troops were withdrawn on 1 November 1919. The garrisons in Homs, Hama,

Aleppo, and Damascus were handed over to Faisal; those on the Syrian littoral

went to the French. Faisal felt deserted. He complained of being handed over

‘tied by feet and hands to the French, insisting that Syria was ‘no more a

chattel for political bargaining than is liberated Belgium.’ 36

The British advised Faisal

to come to terms with the French; he could not do so. In March 1920, the Syrian

General Congress declared the country independent within its ‘natural

boundaries’ including Lebanon and Palestine. This earned a firm rebuke from Curzon,

who pointed out firmly where power lay. ‘The

Allied Armies conquered these countries, and their future […] can only be

determined by the Allied Powers acting in concert.’ 37 The French were

nevertheless subjected to guerrilla attacks along the coast and denied the use

of Aleppo, which was being used to support French troops

in Cicilia fighting Mustapha Kemal. In July 1920, not very

surprisingly, the Hashemite leader was expelled. Syria, declared Alexandre

Millerand, the new French premier, would henceforward be held by France ‘the

whole of it, and forever. 38

The loss of the direct

linkage to the broader Arab hinterland that accompanied Lebanon’s creation as a

separate state (see next article) served to strengthen the power and wealth of

Beirut’s merchants and bankers, who enjoyed a virtual monopoly on foreign

trade. In contrast, smaller cities such as Tripoli in the north and Sidon in

the south, which relied on regional, inter-Arab work, declined economically.

For updates click hompage here