By Eric Vandenbroeck

The story of

Buddhist's past and at least one possible future.

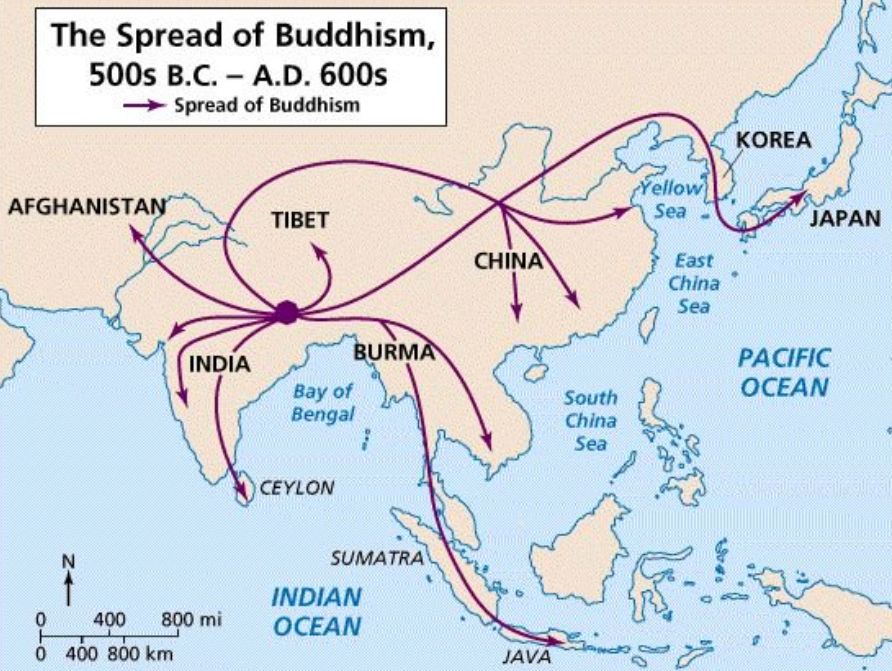

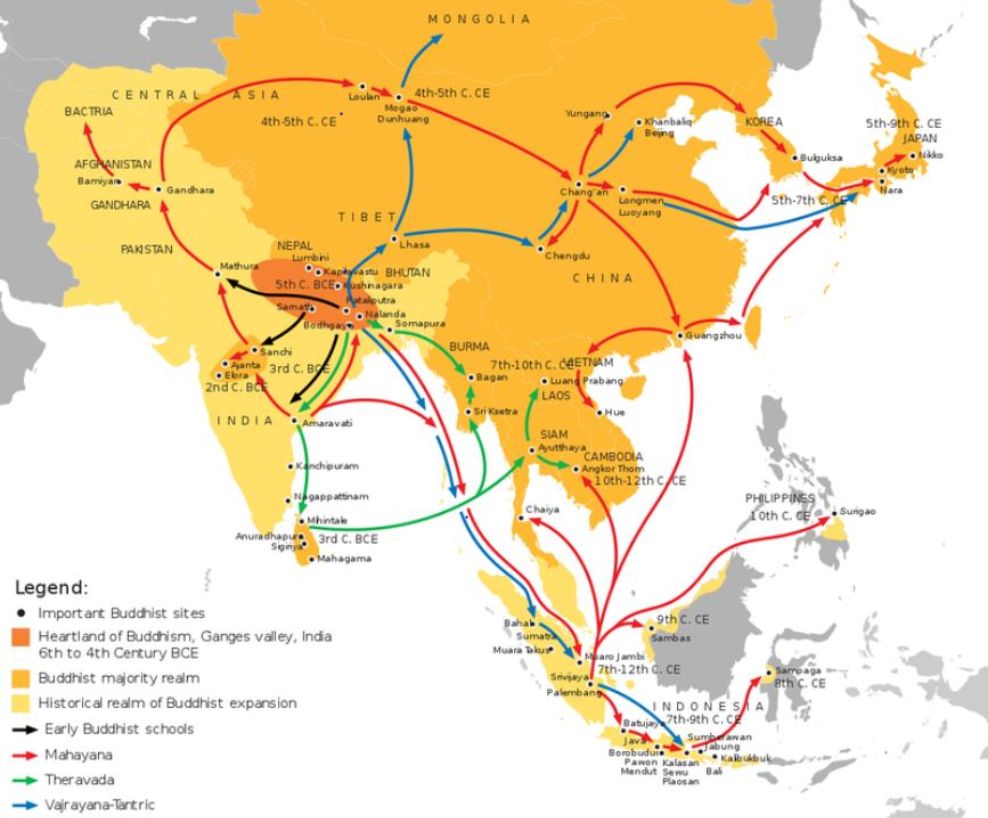

While opinions in

Europe and North America tend to view Buddhism as some sort of unified religion

the origins and spreading of Buddhism tell a different story.

Whereas initially

Buddhism remained confined to northern India for two hundred years it began to

spread under King Asoka’s power (274–232 BC).

Over time, Buddhism

developed into several

distinct branches. Theravada Buddhism, the most conservative school, is

prominent in Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Sri Lanka, and

Myanmar. Mahayana Buddhism, the more liberal, is practiced in East Asian and

South Asian countries such as China and India. Vajrayana Buddhism is most

prevalent in Tibet and other Himalayan countries.

In India, Buddhism

began to wane in the sixth and seventh centuries CE when devotional Hinduism

replaced Buddhism in the south and Hephthalite Huns invaded and sacked

monasteries in the north. By the thirteenth century, repeated invasions by the

Turks ensured that Buddhism had virtually disappeared. By this time, however,

Buddhism was flourishing in many other parts of Asia.

As early as the first

century CE, Buddhist monks made their way over the “Silk Road” through Central

Asia to China. By the seventh century, Buddhism had made a significant impact

in China, interacting with Confucian and Daoist cultures and ideas.

It is also here that

we see one of the examples of the syncretic nature of Buddhism. Thus were in

the beginning Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism vied with one another for the

hearts and minds of the populace, over time they

began to blend together.

In the eighth

century, Buddhism, shaped by the Tantric traditions of northeast India, spread

to the high mountain plateau of Tibet. There, in interaction with the

indigenous Bon religion, and with forms of Buddhism that had traveled to Tibet

from East Asia, a distinctive and vibrant form of Mahayana Buddhism emerged

known as Vajrayana,

the “Diamond Vehicle.”

These streams of

Buddhism are differentiated to some extent by their interpretations of the

Buddha and the Buddha’s teachings, the scriptures they hold in special

reverence, and the variety of cultural expressions they lend to Buddhist life

and practice. It would be a mistake, however, to identify these streams of

tradition too rigidly with either specific ideas or specific geographical

areas.

Western ideas also

influenced other forms of syncretism. Thus, for example, the Buddhist doctrine

of rebirth was read in terms of

contemporary biological insights: humans are but one of many life-forms,

they are not biologically privileged or different, as certain religious

creation myths suggest, but are instead part of a more extensive web of life.

Buddhist cosmologies, according to which there are multiple “world-systems”

that are effectively similar to our own, were read in terms of the findings of

modern astronomy, which posited the existence of innumerable planets orbiting

innumerable stars throughout the universe. Buddhist ontological theories based

on the idea that all phenomena are constituted of tiny, invisible particles

were read as anticipating and according to the worldview of contemporary

physics and chemistry.

For their part, Asian

Buddhist apologists who were subject to polemical arguments from Western

Christians and from Asian modernists who embraced the new scientific theories

and their related technologies and applications tended to resist those

pressures by reinterpreting Buddhist teachings and worldviews according to the

latest findings of science. Charges that Buddhism was unscientific, backward

superstition were countered by Buddhist leaders who argued that Buddhism, properly

understood, was a scientific tradition.

But with current book

titles like "No Self, No Problem: How Neuropsychology Is Catching Up to

Buddhism" (2019) it is the emerging field of psychology that Buddhism is

believed to most closely resemble.

Enter the era of Nationalism and Zen Buddhism

Similarly the

combination of Westerners seeking a religious tradition that accorded with

their worldviews and values and of Asian Buddhists promoting a vision of

Buddhism that was in line with those values resulted in the widespread

perception that Buddhism is, among other things, a religious tradition that is

essentially dedicated to peace and nonviolence. Whereby I have detailed how Buddhism very well lends itself to

Nationalism and even war.

Another example of

this is the Venerable Master Taixu (1890-1947) after

the military conflict between Chinese and Japanese troops in Jinan in 1928, Taixu became a critic of Japanese Buddhists who, according

to him, had detracted from the true Buddhist path by conniving with and

supporting Japanese aggression against China, yet he spared no effort to

persuade them against Japanese imperialistic policy. Meanwhile, he urged

Chinese Buddhists to prepare themselves for and participate in resisting

Japanese invasion, and justified his call as the

way to revive Buddhism.

Following see also Taixu’s

letter to Adolf Hitler:

According to Buddhists

scripture, only Buddhists count as human beings and there is no moral or

karmic issue with killing non-Buddhists. Here, as in other Buddhist sources,

the prohibition against violence is superseded by the imperative to disseminate

and preserve Buddhism.

Beyond such

rhetorical support for violence and warfare, there are also multiple examples

of fighting Buddhist monks. The Buddhist monks of Shaolin Monastery are perhaps

the most well-known examples of warrior monks. Depicted in numerous kung-fu

movies, the Buddhist monks of Shaolin Monastery are renowned for their skill in

the martial arts. Historically, the monks of Shaolin Monastery came to

prominence in the seventh century when they fought on behalf of the Chinese

emperor to defeat Wang Shichong (567–621), a claimant

to the Chinese throne who was defeated by the founders of the Tang Dynasty

(618–907). The fighting Buddhist monks of Shaolin are not an anomaly. The sōhei or “warrior monks” of Japan were effectively monastic

troops that fought on behalf of their resident monasteries against other

warrior monks. They also fought in the Genpei War

(1180–1185), a civil war that resulted in the establishment of the Kamakura

shogunate in Japan. In the massive Buddhist monasteries of traditional Tibet,

monks called dap

dop served as a police force and militia. The dap dop were recognized as

monastic Buddhists, though they carried weapons and did not observe standard

monastic discipline. Perhaps the most striking example of Buddhist involvement

in violence and warfare is the role of the Japanese Buddhist establishment in

the war efforts of imperial Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries. Buddhist monks in Japan supported the wars by providing

justification for the invasion of East Asian nations and the slaughter of their

people as an expression of benevolence and compassion, officers were trained in

Zen Buddhist establishments in order to make them effective soldiers, and

Buddhist monks even formed fighting units. Although Buddhism was presented and

received in the West as an essentially peaceful tradition, several of the early

and most important representatives of Japanese Buddhism in the United States

had ties to the Japanese war effort; Shaku Sōen and

D. T. Suzuki (the latter as we will see further below) had actively promoted a

nationalistic, prowar version of Buddhism, for example.

Similar examples could recently be seen in Myanmar which is contrasted

by the western syncretism of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh who was teaching

comparative religions at Princeton University and went on to become a lecturer

at Columbia University which led to another form of syncretism, that of Buddhist

environmentalism.

As for Zen Hundreds

of books have been written that apply the principles of Zen Buddhism to a wide

range of activities. These “Zen and the Art of . . .” or “Zen in the Art of . .

.” books seemingly cover every possible human endeavor like Lawrence M. Kahn Zen and the Art of Hiring a Personal Injury

Lawyer (2010),Cary Black and Don Black

Zen and the Art of Cooking Beer-Can Chicken (2007), with other titles

like “Zen in the Art of Slaying Vampires”, or “Zen and the Art of Public School

Teaching”, just to name a few. These books reflect the fact that the principles

of Zen may be applied to any activity—from traditional flower arranging and the

preparation, serving, and drinking of tea to archery, small engine repair, and,

evidently, cooking beer-can chicken. Phil Jackson (1945–), the former coach of

the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers, applied the principles of Zen to

professional basketball and won a record eleven NBA titles as a coach (Jackson

2014). Along with books applying the

principles of Zen to any action, the market is saturated with “Zen” products.

These include shoes, lamps and lights, vacuum cleaners, guitars, ceiling fans,

furniture, bassinets, makeup and beauty products, toothpaste, energy drinks,

herbal supplements (for both humans and dogs), e-cigarettes, and liqueur.

As has been described

in William Theodore De Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, and Paul Varley, eds.

Sources of Japanese Tradition. Vol. 1, From Earliest Times to 1600. 2nd

ed. New York: Columbia University Press 2001,this perception of Zen may be

traced in part to the creation of “New Buddhism” (Shin Bukkyō

新佛教) in Japan in the second half of the nineteenth

century.

This New Buddhism

emerged in response to political and social changes attending the Meiji

Restoration. This period of time in Japanese history was initiated in 1868 when

Emperor Meiji (1852–1912) reestablished actual imperial rule and Japan was

rapidly modernized. These moves toward rapid modernization were included in the

so-called Charter Oath (Gokajō no Goseimon

五箇条の御誓文) that was issued upon Emperor Meiji’s enthronement.

Consisting of five articles, the Charter Oath outlines a new direction for the

Japanese government and society. The final two articles of the Charter Oath

articulate the new emphasis on modern science, technology, and worldviews and

the intended abandonment of practices, views, and institutions that were not in

accord with modern, scientific models. Article 4 states that “Evil customs of

the past shall be broken off and everything based upon the just laws of

Nature.” Article 5 reads: “Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as

to strengthen the foundation of imperial rule” (De Bary et al. 2001, p. 672).

Effectively, these articles of the Charter Oath announced a withdrawal of

political and economic support for traditional religious institutions and a new

emphasis on pursuing foreign knowledge, chiefly scientific and technological

knowledge. In response, Japanese Buddhists reframed their religion in order to

argue that Buddhism made important contributions to Japanese society, supported

imperial rule, and was consistent with modern Western science and technology.

Domestically, Japanese Buddhists began to argue that Buddhism was an essential

aspect of Japanese culture, that Japanese Buddhism was, in fact, the only

“true” Buddhism in the world.

Not unlike as was the

case with the above mentioned Venerable Master Taixu

a book by Brian Daizen Victoria titled “Zen at War”(2006) traces Zen Buddhism’s

support of Japanese militarism from the time of the Meiji Restoration through

the World War II and the post-War period.

One of the most

influential person in establishing Zen Buddhism in the Western imagination was

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki (1870–1966), or D. T. Suzuki as he is commonly known

who along with his popularizer, Alan Watts,

first really brought the West’s attention to Zen. Published in 1934, Suzuki’s

An Introduction to Zen Buddhism is still in print and widely read today.

Therein, he presents Zen Buddhism as a “unique order claiming to transmit the

essence and spirit of Buddhism directly from its author” (Suzuki, An

Introduction to Zen Buddhism. New York,1964, p.2). But also here Ichikawa Hakugen, a Rinzai-priest and a scholar who taught at Hanazono University in Tokyo, saw D. T. Suzuki as “most

responsible for the development of imperial-way Zen”, but in no way standing

alone in this development. Hakugen traces this

development to pre-meiji developments. (Victoria, Zen

at War, 2006, p. 167.) Or as Suzuki himself wrote: A good

fighter is generally an ascetic or stoic, which means he has an iron will.

This, when needed, Zen can supply. (As quoted from Daisetz

Teitaro Suzuki, Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture, 1938, p.

62.)

A priest named Mindar

And at least one

possible future of Buddhist syncretism can be seen in the priest named Mindar holding forth at Kodaiji,

a 400-year-old Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan. Like other clergy members, this

priest can deliver sermons and move around to interface with worshippers. But Mindar comes with some ... unusual traits. A body made of

aluminum and silicone, for starters. Mindar is a robot who is predicted he

could one day acquire unlimited wisdom.

For related subjects

see:

Buddhist Dream-Yoga in Tibet, P.1

Buddhist Dream-Yoga in Tibet, P.2

Buddhist Dream-Yoga in Tibet, P.3

The Dance of Lives: The Tulku Game

For updates click homepage here