By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The 'Chinese Nation'

As we early on have

seen, it was in the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China that became

the formation stage of modern Chinese nationalism and the stage of the

proposition and initial usage of the concept of the 'Chinese nation.' Modern

Chinese nationalism developed around the period of the May 4th Movement. And

although Mao Zedong in March 1953 still referred to "Han chauvinism"

to criticize his rival Kuomintang party, this drastically changed following the

1989 Tiananmen crackdown when history

and memory were developed to become a new nationalistic power now for

the CCP.

The centerpiece of

this post-1989 state-sponsored revival of Chinese nationalism was the so-called

patriotic education campaign, a comprehensive program that (even though the

“China proper” of today previously was just one 'part' of the Manchu-run Qing Empire) revamped history textbooks,

reconstructed national narratives, and renovated historical sites and symbols

throughout China.

Where the anti-Mao

Guomindang/KMT leadership deliberately used fear of the loss of territory in

the 1920s and 1930s to rally political support, Deng Xiaoping re-introduced the

Guomindang's “one-hundred-year

history of humiliation” narrative as a new source of legitimacy of the

CCP’s rule and the unity of the 'Chinese' people and CCP society. This was

crowned by a new ongoing yearly National Humiliation Day.

Hence as we have seen

in part one and two, the Chinese

nationalism that once defined Mao Zedong’s China more recently has been

replaced with a form of ethnic nationalism that focuses inward and looks to the

past in a “search for roots” (xungen [寻根]).

Today's creation and the expansionism of China

In a very well

researched overview of Modern Chinese nationalism Dahua Zheng from the Chinese

Academy of Social Sciences, Institute of Modern Chinese History in Beijing

details how the modern notion of China dated to the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries when reformers and revolutionaries adapted

foreign ideas to fortify China against the depredations of Western imperialism.

Whereby in Dahua Zheng's overview, one can also see how this nation-building

project, projected back onto the various empires and states that occupied the

present-day territory of the People’s Republic, and as we have seen, planted the seeds of many of the country’s

most fraught problems, from Xinjiang to Taiwan to the South China Sea.

The Qing dynasty, the

last of China's imperial dynasties, had created a multi-ethnic realm, of which

‘China proper’ – the fifteen provinces of the defeated Ming Dynasty – was just

one part. The previous Ming state lasted for almost 300 years, but it had not

used China's name, either. Before the Ming, those territories had been part of

a Mongol Great-State that had stretched as far as the Mediterranean: East Asia

was just one part of its domain. Before the Mongols, they were controlled by

the rival Song, Xia, and Liao states. These had occupied various parts of the

territory we now call China and they, in turn, were different from the

fragmented conditions that existed before them.

Each state was

different from its territorial extent and its ethnic composition, but each

needed to present itself as the legitimate successor to its predecessor.

Therefore, to retain the loyalty of officials and the wider population, each

new governing elite needed to claim continuity with tradition. To receive the

necessary ‘mandate of heaven,’ it had to speak in certain ways and perform the

rituals expected of a ruling class. In certain eras, this may have been a

genuine belief; in others, it became a political theatre, but it became

outright deception in some. The Mongols and Qing elites inwardly retained their

Inner Asian cultures while externally presenting themselves – at least to a

portion of their subjects – as heirs to the rule's Sinitic traditions. Where,

then, was ‘China’? Until the very end of the nineteenth century, rulers in

Beijing would not even have recognized the name ‘China.’

Both Zhongguo and Zhonghua are translated into English as

‘China,’ but they carry particular Chinese meanings. Zhong Guo is literally the

‘central state’ of an idealized political hierarchy. Zhong Hua is literally the

‘central efflorescence,’ but its more figurative meaning is the ‘center of

civilization,’ an assertion of cultural superiority over the barbarians in the

hinterland. These terms have deep historical roots, but they were not used as

formal names for the country until the end of the nineteenth century.

It is only after the

Republic of China's founding and its intellectuals who had traveled abroad and

were able to look back on their homeland from afar promoted the establishment

and formation of the concept of “Chinese nation.” This is what among others Chang

Naide pointed out in his 1986 book, A Brief History

of the Chinese Nation; Somebody called it Xia(夏);

somebody called it Huaxia(华夏); somebody called it Han people(汉人) or Tang people(唐人). However, Xia(夏), Han(汉), and Tang(唐) are all

dynasty names rather than nation names.1

Who were the people

who founded the Qing state? They were people from what is now northeastern

China, and they spoke a Siberian language: Manchu. In 1644 they had ridden out

of their chilly homeland and taken over the moribund Ming state. They were

people from outside the Zhong Guo, but they quickly realized that if they were

to rule the former Ming domain successfully, they would have to adopt some of

their predecessors' techniques. Yet even while they did so, they remained

Manchu. They continued to rule in an Inner Asian style, which the American

historian Pamela Crossley has called ‘simultaneous ruling.’2 Each part of their

‘great-state’ was ruled differently, according to what was thought culturally

appropriate. Yet at its center, the Manchu language and the script remained the

state's official language and script. The new elite sought to preserve their

traditions: riding, archery, and hunting; rites, prayers, and sacrifices to

ancestors. More importantly, they maintained Manchu regiments – known as banners

– to control the society they had conquered. In effect, from the

mid-seventeenth century, the Zhong Guo became a Manchu ‘great-state’ province.

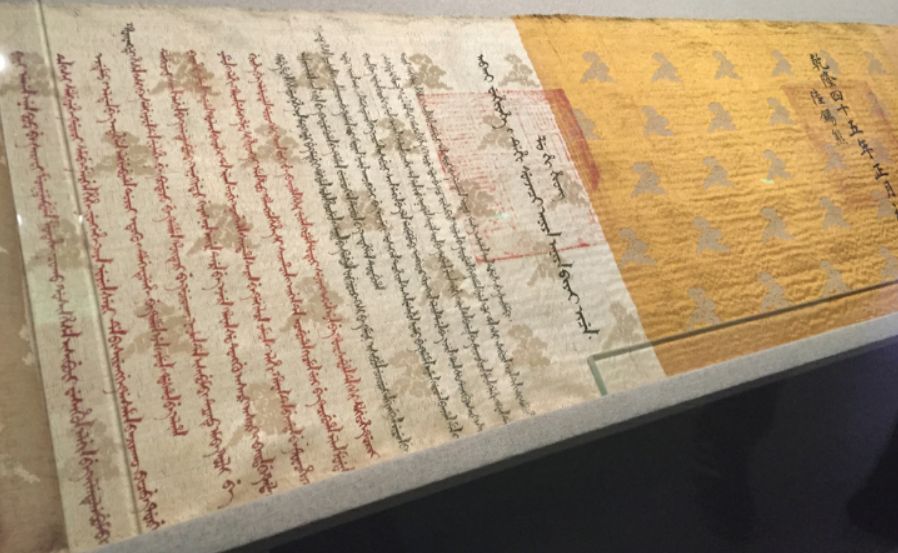

Pictured below a silk

scroll on display in the Shanghai History Museum. Note the Manchu script (left)

used alongside the Chinese characters. The document is the ‘Imperial Mandate to

Parents of Liu Xixiong,' dated 1780:

The following are

emblems of two of the Manchu ‘banners’ on display at the former mansion of

Prince Gong (Manchu name: Yixin) in Beijing. All Manchu and Mongol subjects,

along with some Han, were organized into banners, military units, through which

the Qing Great-State imposed order:

Meanwhile, the Qing

state was busy keeping itself together, keeping out “barbarians” from the north

and west, and trying with mixed success to impose itself on immediate but

determinedly non-Han neighbors Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Even in the trade of

ideas, China can scarcely claim superiority given how much is imported from

India, Persia, Central Asia, and, most recently, the west.

It was the attacks by

Europeans and Americans on “China Proper” after 1840 and then defeated by Japan

in the war of 1895 that forced the Qing to engage with the outside world on new

terms. Those clashes fused pre-existing Sinitic ideas of an “all-powerful”

ruler with Western ideas of states' separateness to create an idea of

sovereignty as a moral order rather than simply a legal arrangement. In

contemporary China, sovereignty is defended as a moral imperative, a matter of

life and death, rather than a convenient way to organize a complex

international society.

The word 主权 - sovereignty was initially introduced to modern

Chinese vocabulary thru William A. P. Martin's translation of Henry Wheaton's

Elements of International Law in 1864. Previously it was also translated as 薩威棱貼. Martin's translation became definitive and also

traveled to Japan. So this most important term in the international relations

of modern China was coined by an American.

“China proper” – the

former Ming state which the Qing invaded in 1644 – at this point was just one

part of the Manchu-run Qing Empire state. The nationalists had to

invent why the non-Chinese parts – Tibet, Xinjiang,

Mongolia, and Manchuria – should remain part of this new country. People like Zhang Taiyan would

have been happy to discard the outer regions and focus on an “ethnically pure”

center. Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen wanted to keep all the territory. This,

ultimately, is the cause of the current unrest in Xinjiang, Tibet, and even

Inner Mongolia.

As we have seen, the

Nationalist textbook writers and

map makers faced a pedagogic and deeply political problem. How could

they persuade a child in a big coastal city, for example, to feel any

connection with a sheepherder in Xinjiang? Why should they even have a

connection? The general purpose of human geography was to explain how varying

environments had created groups with differing cultures. However, nationalism

required all these different groups to feel part of a single culture and loyal

to a single state. It was up to nationalist geographers to resolve the puzzle.

They found two main ways to do so. One group of textbook authors stated that

all Chinese citizens were the same: they were members of a single ‘yellow’ race

and a single nation, and no further explanation was needed. However, a second

group acknowledged that different groups did exist but were nonetheless united

by something greater. Within this group, some authors made use of ‘yellow race’

ideas; some used the idea of a shared, civilizing Hua culture. In contrast,

others stressed the ‘naturalness’ of the country’s physical boundaries.

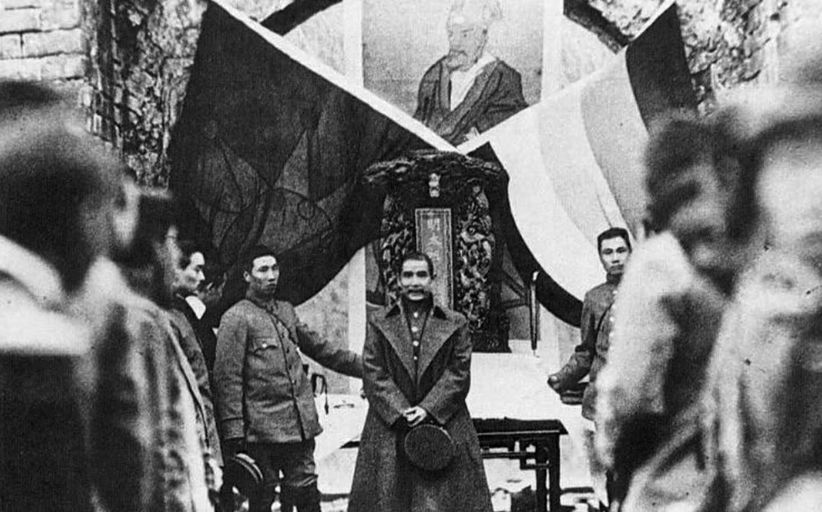

Underneath Sun Yat-sen

was flanked by the flags of the nascent Republic of China. On the right, the

‘Five Races Under One Union’ flag and, on the left, the ‘Blood and Iron’

eighteen-star flag of the Republican army. On 15 February 1912, the day the

Qing court formally abdicated power.

Thus, we see the two

potential futures for China on the Left Han national flag representing the 18

provinces of the former Ming on the right the flag representing the five races

showing a multi-ethnic future'.

When Angela Merkel embarrassed Xi Jinping

As seen in part one,

the CCP party and state remain insecure as they continue to re-write history,

which was apparent in 2014 German

Chancellor Merkel presented to President Xi an 18th-century German map of China based on a famous 1718 Qing “Overview of the

Imperial Realm.” It only showed “Sinae Propriae”

(China Proper), not the other Qing territories or Taiwan. The Chinese

delegation did not know how to react. The protocol required appropriate

gratitude, but this was not a gift to be celebrated back home. Was it simply an

innocent gesture of goodwill or a deliberate snub by the German government?

The Chinese state

media editors were in a quandary and resolved it in the traditional manner of a

one-party state: they faked the news. They reported the map's gift but then

replaced the picture of the actual map that Merkel had presented to Xi with one

of a completely different map, one that portrayed a much larger territorial

claim. This was actually drawn over a century later, in 1844 by a British

map-maker John Dower, and included the Qing’s eighteenth-century conquests of

Tibet and Xinjiang within the empire’s frontiers.3 In fact, the map showed

frontiers drawn much wider than the People’s Republic's current borders. This

inaccuracy was not a problem for the Chinese media.

This might appear to

be an amusing anecdote on the surface, but it also demonstrates the anxiety and

paranoia that lurk just beneath the surface of contemporary China’s politics.

If Xi had given Merkel a map of eighteenth-century Prussia that excluded most

western Germany, the object would have been treated as an interesting curio.

The People’s Republic’s sense of self, on the other hand, is far too fragile to

admit that the shape of the country may have been different 300 years ago. No

debate over the state’s ‘core interest’ of territorial integrity is permitted,

and the result is absurd denials of any historical evidence that underpins a

different story of the past. The only acceptable version of history is the

invented version that suits the Communist Party’s current leadership's needs.

The party depends on these invented narratives. As it retreated from Maoist

communism in the late twentieth century, it searched for new ways to generate

its citizens' loyalty. One key foundation of its right to rule became

‘performance legitimacy’: the delivery of ever-higher living standards to most

of its population. However, proletarians and bourgeois cannot live by bread

alone, and the party also sought a new guiding idea to fill their souls and

lead them in the right direction. The new people’s opium would be nationalism –

not the kind that makes mobs march through the streets, but an official kind,

defined by those at the top and stressing homogeneity and obedience.

In part two, 'The language wars' buried deep

within the language project fear that China might be too diverse to hold

together. This is a fear with deep roots, yet it remains too sensitive to be

spoken out loud. We can only hear its echoes when Xi and his fellow leaders

talk about the need for a ‘culturally harmonious country’ and constantly call

for ‘unity.’ Disharmony and disunity are the concerns-who-must-not-be-named.

The idea that Hong Kong or Taiwan – or Guangzhou or Shanghai – might have their

own identities stronger than their Chinese national identity is literally

unimaginable for those who lead the People’s Republic.

From the ‘yellow’ race to 'Han' Nationalism

In their book about

Han-centrism by John Friend and Bradley Thayer wrote:

"China is a

hyper nationalistic state and very proud of this fact. This must be recognized

to compel all international actors, states, non-government organizations, human

rights groups, academics, media, celebrities, and individuals, to think through

the consequences of the rise of China for what they believe and value and how

China’s ascent will affect their beliefs and values."4

Although Han Chinese nationalism and Chinese nationalism are

different in terms of ideology, with the latter often focusing on more

multi-racial nationalism, however, due to China's historical and current

control by the ethnic Han Chinese, the two have been connected and frequently

used together. The concept was first debated in the early 20th century; one of

those debating it was Zhang Taiyan, who strongly

opposed the idea of a proposed multi-racial nationalism of Yang Du and Liang

Qichao and stressed the Han ethnic bloodline as evidence for the greatness of

China and rejected any notion for a multiethnic China, being skeptical of

non-Han ethnic groups like Manchus, Mongols, Tibetans, and Turkic Muslims.

Zhang Taiyan strongly criticized non-Han ethnic

groups, notably Manchus, who accused the Manchus and other non-Han peoples as

oppressors and believed they were impossible to be assimilated, if not say,

understanding Han Chinese culture and customs. There were, however, significant

proponents of a multi-racial form of Chinese nationalism as well, and Tibet and

Xinjiang remained independent during the rule of the Republic of China.

As explained, the

early Republic of China was not only the era of the early stage of modern

Chinese nationalism (Zheng, 2006a, b) but also the stage of proposition and initial use of the

concept of “Chinese nation(中华民族).” First, to put forward and use the concept of

Nation of China(中国民族)

was Liang Qichao.

In China’s great race

to the 21st century, Liang was the man with the starting gun. His concept of

Chinese nationalism was pivotal (including in China today) to the May Fourth Movement and

all that came after.

Liang believed the

nation was in an existential struggle with the white race. Talk of division,

therefore, was literally suicidal: strength could only come from intermingling.

There could only be one nation, and everyone in Zhongguo

needed to be a part of it: there was no space for separate identities. In his

view, it went without thinking that the Han were the core of the Chinese

nation, and everyone else just had to assimilate. This didn’t just apply to

other ethnic groups; Liang was equally uninterested in Han's local differences.

Resistance to the outsider was far more important than minor differences

between insiders. Liang’s vision of the nation was both ethnic and cultural.

What kept the Zhonghua minzu together and allowed it

to overcome invaders was its superior culture. This superior culture

assimilated all those with whom it came into contact. Therefore, the history of

the Chinese nation was the story of the progress and expansion of this culture.

Liang downplayed

similarities that could have provided grounds for a different ‘natural’ order.

For example, Mongols and Tibetans share a Buddhist culture, together with

people in Nepal and northern India. Mongol, Tibetan, and Manchu societies share

a tradition of shamanism.

The Islamic Turkic

peoples have cultural connections with peoples all the way west to Istanbul,

and highland ‘Miao’-type minorities can be found throughout Southeast Asia.

These cultures are all quite different from that of the Han people of the

central plains. Still, Liang minimized the differences and emphasized

similarities to highlight the unity of Zhongguo-ness.

As a result, his logic would preserve the Qing’s ‘five ethnicities’ (Manchu,

Han, Mongol, Turkic, and Tibetan), along with their five respective

territories.

These were choices he

made in the early 1900s for clearly political reasons, but the consequences of

those ideas have long outlasted the Qing Great-State. To this day, the Chinese

‘national history’ is usually written as a history of a territory that was not

actually ‘fixed’ until the middle of the twentieth century.

Underneath the

diplomat and poet Huang Zunxian (center) with some of

his family. He was one of the pioneers of the ‘yellow race’ thinking in the

late Qing period but later helped ensure the Hakka people were classified as

part of the ‘Han race.’

The beauty of the

‘Han race’ idea for the revolutionaries also created a huge community of

potential supporters who could be mobilized against a declared enemy: the

ruling Manchu elite. If the Manzu were excluded, then

so were the Mengzu (Mongols) and the non-Chinese-speaking minorities. Indigenous groups were

relegated to the status of ‘browns’ or ‘blacks’ for whom Social Darwinism

predicted only one fate: they could be ignored in the coming struggle.

Increasingly, the revolutionaries – mainly young, male students living in exile

in Japan, mixed old ideas of lineage, zu, with new

racial ideas of biological race – Zhong. The fusion of Zhong and Zu was made

possible by the imaginary figure of the Yellow Emperor: Huangdi became the

father of the zhongzu. However, the question of who

was and was not, a member of the zhongzu (种族 zhǒngzú) was not

always so easy to answer.

Zhang Taiyan tried to establish a social, cultural, and spiritual

identity of Chinese, which could counterbalance the West's dominant influences.

The Republic of China is the name he gave to a newly emerged Chinese nation

after the overthrow of the Qin Dynasty.

The multifaceted

image of the Han Chinese nationalism further developed in the buildup of modern

Chinese statehood. Han Chinese nationalists had created a hostile opinion

towards ethnic Uyghurs and Tibetans, viewing them as dangerous for the Chinese

state due to its cultural differences and lack of sympathy for ethnic Han

Chinese.

Almost every state has

a history that goes back at least 5,000 years in the sense that people have

inhabited most of the earth’s surface for at least that long. The claim of a

5,000-year history for China is intended to link it to the mythical birth-date

of the mythical “Yellow Emperor” in 2698 BCE. The Yellow Emperor was chosen as

the spiritual father of all Chinese by the man who invented the “Han Race” in

1900, Zhang Binglin. Zhang wanted to create a racial

boundary between the Manchu rulers of the Qing Great State and the people he

defined as the “Han,” and he did so in his Qiushu (the “Book of Urgency”) in

which he traced the origin of all the Han to the Yellow Emperor.

This is a racial

vision in which all true Chinese are descendants from a single ancestral stock.

It is quite at odds with all the empirical evidence from genetic and linguistic

research on the very diverse population of the People’s Republic of China. Nonetheless,

it seems to underpin Xi Jinping’s “steamroller” approach to diversity in the

PRC, the enforced homogenization of identity under the banner of the “five

identifications.” A loyal PRC citizen is obliged to identify with the

motherland, with the Chinese nation (Zhonghua minzu),

with Chinese culture, the Chinese socialist road, and the Communist Party

itself. This can only make sense if Xi Jinping believes a single nation has a

single culture.

This thinking was

given extra urgency by incidents of ethnic violence and protest in Tibet and

Xinjiang during the 2000s when several influential figures in the PRC came to

view the notion of separate minzu as a threat to the

country’s future.

This emerging what is

also termed 'continentalism' is in keeping with an expansionist foreign policy

line that has paved the way for a geostrategic outlook oriented towards expansion.

Thus there are

clearly plenty of people, at all levels of Chinese society today, who believe

their state is more than ‘first among equals’ but use a particular vision of

the past as justification for a new imperial outlook. It is made worse by

expressions of Han chauvinism towards foreigners and treating ‘overseas

Chinese’ in these countries as ‘racial allies’ and as tools of state policy.

Re-invoked by the

present-day Communist Party of China (CPC), annual ceremonies are held to worship the

imaginative Yellow Emperor.

Due to the coronavirus, this year, to a large degree, was held online.

The origin of

contemporary China’s ‘sovereignty fundamentalism’: a hybrid of Confucian

chauvinism and American legalism. It melds premodern ideas of the cultural

pre-eminence of the Zhong Guo with Western ideas of fixed borders and

independence. At its heart lies a philosophical difference: the Chinese word

for sovereignty, zhuquan ( 主權 zhǔ quán),

carries the literal meaning of ‘the authority of the ruler’ – it is focused

domestically, not internationally. Zhuquan mandates

the continuation of a morally superior culture within the protection of

inviolable boundaries. It is, in effect, tianxia (天下 tiān xià) with

passport controls, tianxia in one country. This is

not an idea that can tolerate intervention in a country’s internal affairs but

is rather a mandate for the opposite: the exclusion of other states and their

‘international norms,’ whether on human rights or climate change.

Memories of the

dynastic rituals of tribute still underpin ideas about political legitimacy in

communist China. The Beijing leadership frequently deploys the performance of

rituals of international respect as a status of delegations attending a ‘Belt

and Road Forum,’ or a G20 summit, are widely publicized and help confer a

modern ‘mandate of heaven’ upon the Communist Party. By contrast, critical

commentary on the party’s performance is kept away from the people. The idea of

international delegations traipsing across the ancestral land, ‘measuring,

reporting and verifying’ its carbon emissions and then telling the world that

Beijing is not living up to an internationally agreed standard remains

anathema. Therefore, the assertion of sovereignty above all else is a means to

avoid disrespect and a loss of domestic legitimacy.

Wang Huning is the

brain behind Xi Jinping, just as he was the theoretician behind Xi’s

predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. He currently sits at the apex of

political life in China: on the Standing Committee of the Politburo. As a law

professor at Fudan University, his first book was entitled Guojia

Zhuquan – ‘National Sovereignty.’5 In it, he argued

that the Chinese word zhuquan pre-dates the Western

concept of sovereignty.6 We have come full circle. Wang’s predecessors fought

in vain to prevent the concept of sovereignty from taking root in Beijing. Wang

now claims China invented it and wants to own and control its meaning. He has

chosen to ignore the roles of both the American diplomat Henry Wheaton and the

American missionary, William A. P.Martin, who worked

to bring the zhong guo (中 国 - Zhōngguó)into the modern

world by re-creating the meaning of zhuquan. This

‘strategic ignorance’ of the foreigners’ intermediary roles enables Wang’s

wider philosophical project: to fill Western concepts with Chinese meaning to

underpin Beijing’s plans for a world based upon the notion of a ‘community of

common critical element of its domestic political messaging. The number and

size and destiny’. It fits neatly with a modern version of tianxia,

in which Beijing sits, once again, at the top of a regional, or even global,

hierarchy. It is a hierarchy open to all, as long as they know their place.

The re-invention of Taiwan

While we have seen

that Chiang Kai-shek initially had no interest in Taiwan, and in his speech on

‘The Anti-Japanese Resistance War and the Future of Our Party,’ Chiang even

argued, ‘We must enable Korea and Taiwan to restore their independence and

freedom. Even more so, Mao's Communist Party had long supported independence

for Taiwan rather than reincorporation into China. At its sixth congress in

1928, the party had recognized the

Taiwanese as a separate nationality.

While China could not

afford a military conflict with the USA but could if wanted invade Taiwan, also

there its arguments as having my rights in reference to Taiwan are baseless.

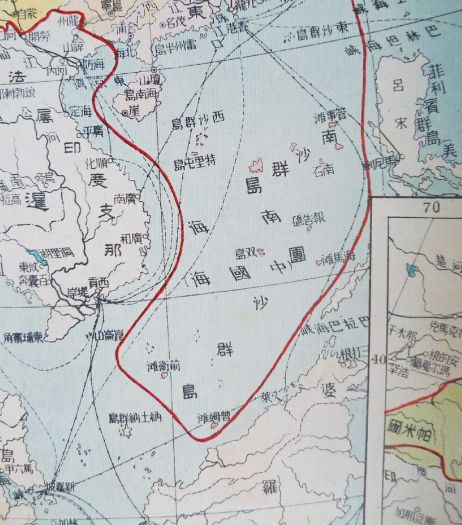

Underneath map of the

South China Sea drawn by Bai Meichu (who probably never went to sea in his life) for his

New Atlas of China’s Construction in 1936. James Shoal (off Borneo), Vanguard

Bank (off Vietnam), and Seahorse Shoal (off the Philippines) are drawn as

islands, yet in reality, they are underwater features. Almost none of the

islands that Bai drew in the central and southern parts of the South China Sea

actually:

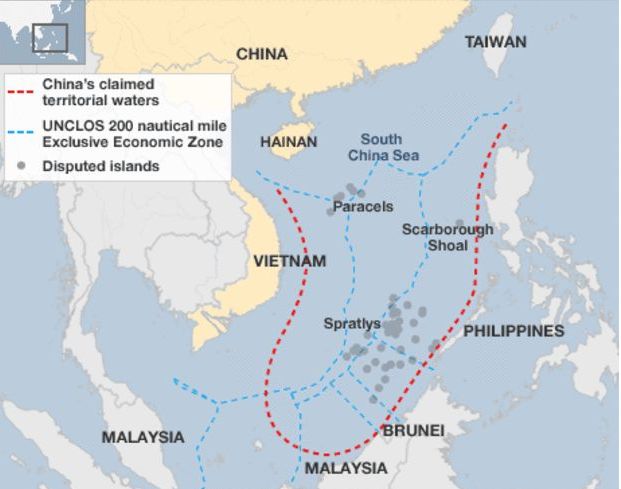

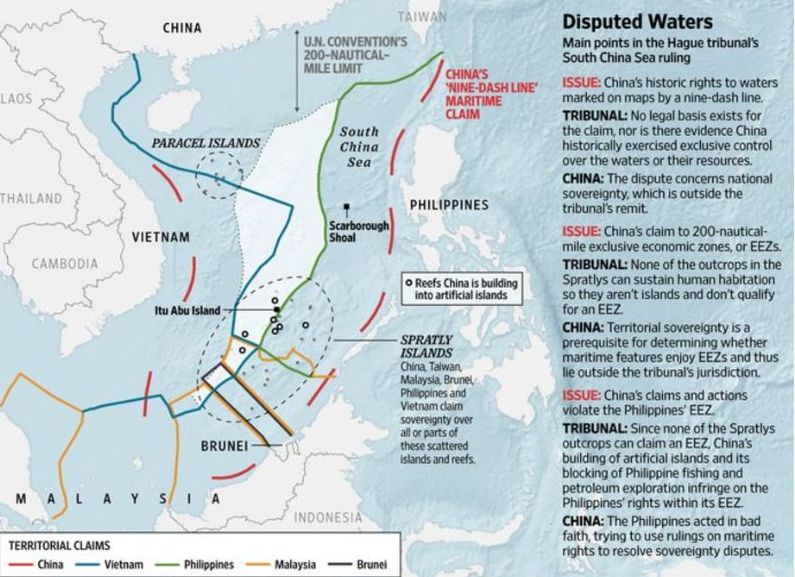

The reinvention of the South China Sea

The ‘Land and

Water Maps Review Committee’ did not have the capacity to undertake its

own surveys, however. Instead, it undertook a table-top exercise: analyzing

maps produced by others and forming a consensus about names.

When it came to the

South China Sea, it is clear from the committee’s conclusions that its leading

references were British, which had far-reaching consequences. On 21 December

1934, the Review Committee held its twenty-fifth meeting and agreed on Chinese

names for 132 South China Sea features. All of them were translations or

transliterations of the names marked on British maps. For example, in the

Paracels, Antelope Reef became Lingyang jiao, and

Money Island became Jinyin dao (金銀島 Jīn yín Dǎo) –

both direct translations.

We know exactly where

the committee’s list of island names came from. It contains several mistakes,

which are only found in one other document: the ‘China Sea Directory’ published

by the UK Hydrographic Office in 1906. This British list is the origin of all

the names now used by China. Some of the names on the list had Chinese origins,

such as Subi Reef in the Spratlys, while others had

Malay origins (such as Passu Keah in the Paracels). Still, British navigators

coined more than 90 percent translating these names caused some difficulties

and a legacy that disturbs the region to this day.

The committee members

were confused by the English words ‘bank’ and ‘shoal.’ Both words mean an area

of the shallow sea: the former describes a raised area of the sea bed, the

latter is a nautical expression derived from Old English meaning ‘shallow.’

However, the

committee chose to translate both into Chinese as tan, which has the ambiguous

translation of ‘sandbank,’ a feature that might be above or below water. Sea

Horse Shoal, off the Philippines, was dubbed Haima Tan; James Shoal, just 100

kilometers off the coast of Borneo, was given the name Zengmu

tan, and Vanguard Bank, off the southeastern coast of Vietnam, was given the

name Qianwei tan. Zengmu is

simply the transliteration of ‘James,’ Haima is the Chinese for seahorse. Qianwei is a translation of ‘vanguard’ and tan, as

mentioned above, is the erroneous translation of ‘bank’ and ‘shoal.’ As a

result of this bureaucratic mistake, these underwater features, along with

several others, were turned into islands in the Chinese imagination. Ultimately

this screw-up s the reason why the Sapura Esperanza was harassed while drilling

for gas near the James Shoal eighty-five years later. China is prepared to go

to war over a translation mistake.

The committee

conferred the Chinese name Tuansha on the Spratlys. The name vaguely translates as ‘area of sand.’ In

1935 however, neither the committee nor the Chinese government was prepared to

claim the Spratlys.

The man who caused

China to claim non-existent islands hundreds of kilometers from its shores was

a Manchu who probably never went to sea in his life. Bai Meichu

was born into relatively humble origins in 1876 in Hebei province, 200

kilometers due east of the Forbidden City.

He became a schoolteacher

and then a teacher of teachers at the Women’s Normal School in Tianjin. There

he taught, among others, Deng Yingchao, a future

senior cadre in the Communist Party and the wife of Zhou Enlai. At the same

time, he was becoming a pioneer in the new subject of geography. This was not

yet geography as the later generation of the above mentioned Zhu Kezhen, and Zhang Qiyun would

come to define it but a hybrid of old ideas and new nationalism.

In 1909 Bai became

one of the ‘China Earth-Study Society’ (Zhongguo Dixue Hui). According to the historian Tze-ki Hon, none of

its members had any professional training in the subject. Instead, they

recruited members from the old literati. Like Bai, they were people who had

once expected to join the scholar-bureaucracy but were now struggling to

adapt.7

Members of the China

Earth-Study Society were also profoundly influenced by Social-Darwinism. In the

first issue of their ‘Earth-Study Journal’ (Dixue Zazhi) they collectively declared: ‘The cause [of the rise

and fall of power] is due to the level of geographical knowledge each group.

Thus, the level of geographical knowledge directly impacts a country, and it

can cause havoc to a race. It is indeed [a manifestation of] the natural law of

selection based on competition.’ In other words, the size of any group’s

territory ebbed and flowed depending on its relative civilization. In society's

view, China had advanced early but then retreated in the face of Western

advances. The only way to regain strength was to master geography. In the words

of Bai himself in 1913, ‘Loving the nation is the top priority in learning

geography while building the nation is what learning Geography is for.’8

A turning point for

Bai, like so many other intellectuals of the time, was the Versailles peace

conference's outcome in 1919. The decision to hand over the former German enclave in Shandong to Japan enraged

students and the Earth-Study Society members. Their journal carried several

articles denouncing the decision and urging the government to prevent the

expansion of Japanese influence on the peninsula.

At around this time,

Bai became a mentor to a young Li Dazhao, who had

also studied at Jingsheng College and would become

one of the founders of the Communist Party in 1921. It is possible that some of

Bai’s energetic views on geography and national territory were passed directly

into the communist movement.9

In 1929 Bai lost his

teaching post at Beijing Normal University and moved to the women’s equivalent,

instead. In 1935 he left university teaching altogether.

By chance, he came

across the ‘Programme for National Reconstruction’

(Jianguo fanglue) that Sun Yat-sen had

published in 1920, during his time in the political wilderness. This book

inspired him to devote his remaining years to Sun’s mission from Bai's own

account: from Bai's own account using geography to enable national reconstruction.

In 1936 Bai gave the

world his lasting legacy: a line drawn through the South China Sea. It was

included in a new book of maps, the New Atlas of China’s Construction (Zhonghua

jianshe xin tu), that Bai published for schools. He included some of

the new information about place names and frontiers agreed upon by the

government’s Maps Review Committee, published the year before. As was typical

of maps of this period, the atlas was, in many places, a work of fiction. A

bright red borderline stretched around the country, neatly dividing China from

its neighbors. The line was Mongolia, Tibet, and Manchuria, plus several other

areas that weren’t actually under the republican government's control. However,

the fictitiousness reached spectacular levels when it came to the South China

Sea.

It is clear that Bai

was quite unfamiliar with the South China Sea geography and undertook no survey

work of his own. Instead, he copied other maps and added dozens of errors of

his own making – errors that continue to cause problems to this day. Like the

Maps Review Committee, he was completely confused by the portrayal of shallow

water areas on British and foreign maps. Taking his cue from the names on the

committee’s 1934 list, he drew solid lines around these features and colored

them in, visually rendering them on his map as islands when in reality, they

were underwater. He conjured an entire island group into existence across the

sea center and labeled it the Nansha Qundao – the

‘South Sands Archipelago.’ Further south, parallel with the Philippines coast,

he dabbed a few dots on the map and labeled them the Tuansha

Qundao, the ‘Area of Sand Archipelago.’ However, at

its furthest extent, he drew three islands, outlined in black and colored in

pink: Haima Tan (Sea Horse Shoal), Zengmu Tan (James

Shoal), and Qianwei Tan (Vanguard Bank).

Thus, the underwater

‘shoals’ and ‘banks’ became above-water ‘sandbanks’ in Bai’s imagination and on

the map's physical rendering, he then added innovation of his own: the same

national border that he had drawn around Mongolia, Tibet, and the rest of ‘Chinese’

territory snaked around the South China Sea as far east as Sea Horse Shoal,

south as James Shoal and as far southwest as Vanguard Bank. Bai’s meaning was

clear: the bright red line marked his ‘scientific’ understanding of China’s

rightful claims. This was the very first time that such a line had been drawn

on a Chinese map. Bai’s view of China’s claims in the South China Sea was not

based upon the Review Committee’s view of the situation, nor that of the

Foreign Ministry. The result of the confusion generated by Admiral Li Zhun’s

interventions in the Spratly crisis of 1933, combined with the nationalist

imagination of a redundant geographer without formal academic training. This

was Bai Meichu’s contribution to Sun Yat-sen’s

mission of national reconstruction.

According to the

Taiwanese academic Hurng-Yu Chen, ‘Director-General of the Ministry of the

Interior Fu Chiao-chin . . . stated that the publications on

the sovereignty of the islands in the South China Sea by Chinese

institutions and schools before the Anti-Japanese War should serve as a

guidance regarding the territorial restoration issue.’ In other words, the

government would be guided by putative claims made in newspapers in the 1930s.

The meeting agreed that the entire Spratly archipelago should be claimed.

Still, given that only Itu Aba (Taiping Dao) had been physically occupied, the

claim should wait until other islands had actually been visited. This never

happened, but the claim was asserted nonetheless.

A key part of

asserting the claim was to make the names of the features in the sea sound

more Chinese. In October 1947, the RoC

Ministry of the Interior issued a new list of island names. New, grand-sounding

titles replaced most of the 1935 translations and transliterations. For

example, the Chinese name for Spratly Island was changed from Si-ba-la-tuo to Nanwei

(Noble South), and Scarborough Shoal was changed from Si-ka-ba-luo (the transliteration) to Minzhu

jiao (Democracy Reef). Vanguard Bank’s Chinese name was changed from Qianwei tan to Wan’an tan (Ten

Thousand Peace Bank). The name for Luconia Shoals was

shortened from Lu-kang-ni-ya

to just Kang, which means ‘health.’ This process was repeated across the

archipelagos, largely concealing the foreign origins of most of the names. A

few did survive, however. In the Paracels, ‘Money Island’ kept its Chinese name

of Jinyin Dao and Antelope Reef remained Lingyang Jiao. To this day, the two names celebrate a

manager and a ship of the East India Company, respectively.

At this point, the

ministry seems to have recognized its earlier problem with the translations of

‘shoal’ and ‘bank.’.’ In contrast, in the past, it had used the Chinese word

tan to stand in for both (with unintended geopolitical consequences), in 1947 it

coined a new word, ansha (Ànshā) –

literally ‘hidden sand’ – as a replacement. This neologism was appended to

several submerged features, including James Shoal, which was renamed Zengmu Ansha.

In December 1947, the

‘Bureau of Measurements’ of the Ministry of Defence

printed an official ‘Location Map of the South China Sea Islands’, almost

identical to the ‘Sketch Map’ that Zheng Ziyue had drawn a year and a half

before. It included the ‘U-shaped line’ made up of eleven dashes encircling the

area down to the James Shoal. In February 1948, that map was published as part

of the Atlas of Administrative Areas of the Republic of China. The U-shaped

line – with an implicit claim to every feature within it – became the official

position.

Therefore, it was not

until 1948 that the Chinese state formally extended its territorial claim in

the South China Sea to the Spratly Islands, as far south as James Shoal.

Clearly, something had changed in the years between July 1933, when the

Republic of China government was unaware that the Spratly Islands existed, and

April 1947, when it could ‘reaffirm’ that its territory's southernmost point

was James Shoal. What seems to have happened is that, in the chaos of the 1930s

and the Second World War, a new memory came to be formed in the minds of

officials about what had actually happened in the 1930s. It seems that

officials and geographers managed to confuse the real protest issued by the RoC government against French activities in the Paracels in

1932 with a non-existent protest against French activities in the Spratlys in 1933. Further confusion was caused by the

intervention of Admiral Li Zhun and his assertion that the islands annexed by

France in 1933 were indisputably Chinese.

The imagined claim

conjured up by the confusion between different island groups in that crisis

became the real territorial claim.

Pratas's islands now a conservation zone, from where visitors

can send postcards back home from a mailbox guarded by a cheerful-looking

plastic shark. Not far away is a new science exhibition explaining the natural

history of the coral reef and its rich marine life.

Overlooking the

parade ground (which doubles as a rainwater trap) stands a golden statue of

Chiang Kai-shek in his sun hat, and behind him is a little museum in what looks

like a scaled-up child’s sandcastle.

This museum holds, in

effect, the key to resolving the South China Sea disputes. Its assertion of

Chinese claims to the islets actually demonstrates the difference between

nationalist cartography and real administration. Bai Meichu

may have drawn a red line around various non-existent islands in 1936 and

claimed them as Chinese, but no Chinese official had ever visited those places.

The maps and documents on the museum walls tell the RoC

expedition's story to Itu Aba in December 1946 and a confrontation

with some Philippine adventurers in 1956. Still, in the absence of any other

evidence, the museum demonstrates that China never occupied or controlled all

islands. In the Paracels, it occupied one, or just a few, until 1974, when the

People’s Republic of China (PRC) forces invaded and expelled the Vietnamese

garrison. In the Spratlys, the RoC

occupied just one or two. The PRC took control of six reefs in 1988 and another

in 1994.

In the meantime, the

other countries around the South China Sea – Vietnam, the Philippines, and

Malaysia – took control of other features. The real history of physical

presence in the archipelagos shows how partial any state’s claim actually is.

The current mess of

rival occupations is, with some exceptions, the only one that has ever existed.

Understanding this opens a route to resolving the South China Sea disputes. By

examining the historical evidence of occupations, the rival claimants should

understand that there are no grounds for them to claim sovereignty over

everything. They should recognize that other states have solid claims to

certain features and agree to compromise. As the legal phrase goes, uti possidetis, ita possideatis – ‘as you possess, thus may you [continue to]

possess.’ Why should this be so difficult? Ultimately, it is because of the

emotional power that these territorial claims continue to exert. And those

emotions first stirred in Guangzhou in 1909.

Conclusion

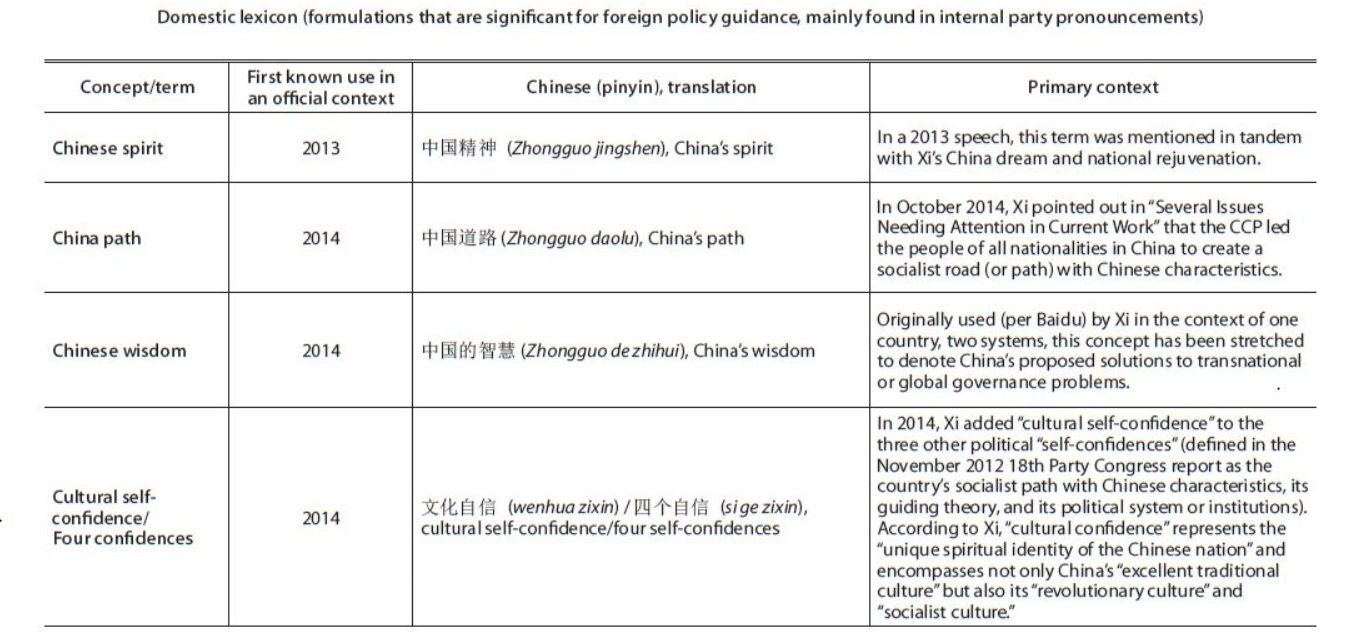

Under Xi Jinping, the

party has doubled down on the narrative. On 29 November 2012, shortly after

being anointed party general-secretary, Xi delivered a speech at

the National Museum of China in Tiananmen Square in which he unveiled his

big idea, the ‘China Dream’ [Zhongguo Meng (中国梦; pinyin: Zhōngguó

Mèng)]. He declared, ‘Achieving the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation

[Zhonghua minzu (中华民族; Pinyin: Zhōnghuá Mínzú)] is the

greatest dream of the Chinese nation in modern times.’ Which goal is

‘resuming China’s historical international status’.

And as seen above,

there are many loaded ideas packed into that five-word phrase. What does Yan

mean by ‘resuming’ or ‘China’ or ‘status’? Which period of history is his

reference point? In the same interview, he glibly mentions the Han Dynasty of

2,000 years ago, the Tang Dynasty of 1,000 years ago, and the early part of the

Qing Dynasty, 300 years ago. It requires a nationalist imagination to regard

these three utterly different states as all representing an essential, timeless

‘China’. It demonstrates how every group that chooses to see itself as a nation

constructs myths around itself and, if they are successful, reconstructs the

state around those myths. Earlier East Asian states (‘dynasties’) did exactly this: they

sought to present themselves as the legitimate successors to their discredited

predecessors.

Xi thus extended

support in the party and the society by appealing to nationalistic sentiment by

trumpeting the “Chinese Dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”

and pursuing foreign policies for expanding the “core interests.” Xi also

played up China’s international leadership by promoting the “Major

Country Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics.” Similarly, the Belt and Road Initiative strengthens

Chinese strategic autonomy by enhancing its key positions along with networks

of capital and infrastructure around the world, foster asymmetric partnerships,

maximize its influence and consolidate

its control overland routes from Central Asia to Europe and the SLOC beyond

the South China Sea.

The People’s Republic

is now an ethnocracy, a racially defined state, still in thrall to the

nationalist myths constructed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries. Under Xi Jinping, the Communist Party has worked to impose ever

tighter boundaries around legitimate expressions of Chinese-ness. Xi and his

fellow leaders have put increasing emphasis on the ‘four identifications’, and

added a fifth. They insist that all Chinese citizens must identify with the

motherland, with the Chinese nation (Zhonghua minzu),

with Chinese culture, the Chinese socialist road,– and the Chinese Communist

Party itself. It hardly needs saying that the party regards any suggestion that

a Tibetan

or an Uyghur

might prefer to live under another government, that a Mongol might not be

willing to embrace a homogenizing view of the nation, that speakers of regional

topolects might prefer not to speak Putonghua, or that any of them might reject

the leading role of the Communist Party, as treasonous. As we are seeing in

Hong Kong (at the time of writing), Xi Jinping’s problem is that the more

worried the Communist Party becomes about national fragmentation, the more it

tries to impose national unity, and the more it generates a reaction in the

opposite direction.

How should the region

and the world respond to these historical myths? They need to be taken

seriously as drivers of Chinese behavior but not as statements of historical

truth, still less as a guide to the correct order of society or regional

relations. Too many people have already been taken in: there are plenty of

foreign commentators happy to parrot lines about ‘5,000 years of superior civilization’ or ‘the

unity of the Han race’, without any understanding of where these concepts come

from. As a result, they give Chinese nationalism a free pass. A country that

believes it has a superior civilization, that its population evolved separately

from the rest of humanity and that it has a special place at the top of an

imperial order will always be seen as a threat by its neighbors and the wider

world. Chinese nationalism is (as Anthony D. Smith has shown) subject to a

critique just as much as any other form.

1. Chang Naide 1986. A Brief History of the Chinese Nation, 中华民族小史. Shangxi: Aiwen Bookstore, 爱文书局 pp5–6

2. Pamela Kyle

Crossley, ‘The Rulerships of China: A Review Article’,

American Historical Review, 97/5 (1992), pp. 1471–2.

3. Marijn

Nieuwenhuis, ‘Merkel’s Geography: Maps and Territory in China’, Antipode, 11

(June 2014),

https://antipodefoundation.org/2014/06/11/maps-and-territory-in-china/

4. John M. Friend

(Author), Bradley A. Thayer (Author) How China Sees the World: Han-Centrism and

the Balance of Power in International Politics, 2018, p.131.

5. Yi Wang, ‘Wang

Huning: Xi Jinping’s Reluctant Propagandist’, http://www.limesonline.com, 4

April 2019,

http://www.limesonline.com/en/wang-huning-xi-jinpings-reluctant-propagandist

6. Haig Patapan and Yi Wang, ‘The Hidden Ruler: Wang Huning and the

Making of Contemporary China’, Journal of Contemporary China, 27/109 (2018),

pp. 54–5.

7. Wu Feng-ming, ‘On the new Geographic Perspectives and Sentiment of

High Moral Character of Geographer Bai Meichu in

Modern China’, Geographical Research (China), 30/11, 2011, pp. 2109–14.

8. Ibid., p. 2113.

9. Tsung-Han Tai and

Chi-Ting Tsai, ‘The Legal Status of the U-shaped Line Revisited from the

Perspective of Inter-temporal Law’, in Szu-shen Ho

and Kuan-Hsiung Wang (eds), A Bridge Over Troubled Waters: Prospects for Peace

in the South and East China Seas, Taipei: Prospect Foundation, 2014, pp.

177–208.

For updates

click homepage here