By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Developing Modern China

Mao Zedong in March 1953 referred to

"Han chauvinism" to criticize his rival Kuomintang party, this

drastically changed following the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown when history and memory were developed to

become a new nationalistic power now for the CCP.

Located on the Pearl River (going

directly to the sea), Guangzhou, previously romanized as

Canton, is the capital and largest city of

Guangdong province in southern China.

Early on Guangdong province was

dominated after October 1920 by a veteran revolutionary, General Chen Jiongming,

who nominally served as governor, A progressive, if idiosyncratic, reformer,

much taken with anarchist philosophy, Chen’s slogan ‘Canton for the Cantonese’

reflected the hostility of local interests to the depredations of

extra-provincial troops, as well as his federalist leanings. Whereas Sun Yat-sen aimed to reunite the nation, Chen

and an increasing number of others wished to explore a federal solution to

China’s problems. From his base in the east of the province, Chen had

moved to expel the forces from neighboring Guangxi province who had occupied

Guangzhou and expelled Sun’s regime. Chen allowed Sun to return to Guangzhou in

November 1920, and to re-establish what the Guomindang presented as the

legitimate national government of the republic, wheeling out a few hundred

members of the old parliament elected back in December 1912 who voted to make

Sun president in May 1921.

An estimated 120,000 people processed

through the city on Sun’s inauguration. Chen’s troops, schoolchildren, and

even martial arts practitioners and actresses had their place in the great

demonstration. Naval gunboats fired salutes from the river, and great triumphal

arches had been erected, decorated with electric lights. But after such a heady

Guangzhou spring, tensions between Chen Jiongming’s provincial

ambitions and Sun’s aim to use the province as his base from which to launch a

war of national reunification mounted. The end came in June 1922 when Sun and

his government were expelled after he had stripped his host and protector of

his offices. Outgunned and outnumbered, Sun fled, and not for the first time

with foreign assistance, shipping out of Guangzhou on a British gunboat, but

not before his own gunboats had bombarded Chen’s troops, killing civilians

as they did so. Sun returned, yet again, in February 1923, having bought the

services of mercenary units from Yunnan province, who drove Chen out. So it

seemed to go, so it threatened to go on and on, revolutionizing the French

farce with rapid exits and plot changes. But it was a dark and sanguine comedy,

for lives were lost in each act, and rarely were they those of the principals.

It was 26 April 2019, the opening

banquet of the Second Belt and

Road Forum in Beijing. As well as offering fine words about regional

cooperation, Xi wanted to talk about history. ‘For millennia, the Silk Road had

witnessed how countries achieved development and prosperity through commerce

and enriched their cultures through exchanges,’ he told the delegations.

‘Facing the myriad challenges of today, we can draw wisdom from the history of

the Silk Road, find strength in win-win cooperation in the present day and

build partnerships across the globe to jointly usher in a brighter future where

development is shared by all.’1

History, or rather a particular version

of history, underpins events such as this. Through staging and rhetoric, Xi

Jinping presents China as the natural leader of East Asia and perhaps beyond.

The metaphor of the Silk Road is deployed as a diplomatic tool: ultimately, all

its roads lead to Beijing. The tool, ironically, is a European invention. The

name ‘Silk Road’ was probably first coined by an early German geographer, Carl

Ritter, in 1838, originally a European one, imposing an imagined order on a far

more complex and chaotic history, so the very name ‘China’ was adopted by

Westerners and given new meanings which were then transmitted back to East

Asia. Over centuries, Europeans had developed a vision of a place they called

‘China’ based upon scraps of information sent home by explorers and priests and

subsequently amplified by storytellers and orientalists. In European minds,

‘China’ became an ancient, independent, continuous state occupying a defined

portion of continental East Asia.

From 1644 until 1912, ‘China’ was, in

effect, a colony of an Inner Asian

empire: the Qing Great State. The Qing had created

a multi-ethnic realm, of which ‘China proper’ – the fifteen provinces of the

defeated Ming Dynasty –

was just one part. The previous Ming state lasted for almost 300 years, but it

did not use China's name, either. Before the Ming, those territories had been

part of a Mongol Great-State that had stretched as far as the Mediterranean:

East Asia was just one part of its domain. Before the Mongols, they were

controlled by the rival Song, Xia, and Liao states. These had occupied various

parts of the territory we now call China and they, in turn, were different from

the fragmented states that existed before them.

Each state was

different from its territorial extent and its ethnic composition, but each

needed to present itself as the legitimate successor to its predecessor.

Therefore, to retain the loyalty of officials and the wider population, each

new governing elite needed to claim continuity with tradition. To receive the

necessary ‘mandate of

heaven,’ it had to speak in certain ways and perform the rituals expected

of a ruling class. In certain eras, this may have been a genuine belief; in

others, it became a political theatre, but it became outright deception in

some. The Mongols and Qing elites inwardly retained their Inner Asian cultures

while externally presenting themselves – at least to a portion of their

subjects – as heirs to the rule's Sinitic traditions.

Pictured below

is Katō Tomosaburō, Prime Minister of Japan

flanked by Baron Shidehara, who would assume the position of Prime

Minister in 1945, and Tokugawa Iesato, then the

first Prince (公爵) of the Tokugawa clan.

Especially Western

thinkers privileged their ‘China’ over other

political formations in the region and promoted it, conceptually, above its

hinterland. In their minds ‘China’ was the region’s dynamic engine while Inner

Asia only mattered when its horse-borne hordes streamed into China to rape and

pillage. In European eyes, ‘China’ was a constant presence on the historical

stage while Inner Asians were reduced to playing repeated ‘ride-on’ parts

before retreating to the dustbin of history. Hence the ‘Silk Road’. China was

regarded as the driver of trade and Inner Asian states merely as the corridors

through which it passed. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,

this idea of a pre-eminent ‘China’ traveled from Europe to East and Southeast

Asia and found a new home in the private discussions and public journals of

Qing intellectuals. These were mainly people who had traveled abroad (as

exemplified above) and were able to look back on their homeland from afar.

According to

Naomi Standen and other specialist historians, the earliest recorded

inhabitants of this part of East Asia arrived elsewhere. The Xia people were

southerners, perhaps originally from Southeast Asia, who settled the southern

and eastern coastal plains. The Shang and Zhou peoples, on the other hand, seem

to have been nomads who arrived from north Asia. The highland Man people formed

the state of Chu in the early eighth century BCE. In the conventional telling,

these groups were the barbarians, separate from the ‘Chinese.’ Yet according to

the opposite: these ‘barbarians’ were the original inhabitants who adopted a

settled, urban lifestyle and thereby made themselves different from their

wilder relatives – they lived in towns. They were led by an emperor who ruled

through a written language. These were the three markers of early civilization,

not ethnicity. Cities were composed of many ethnic groups members, but by

adopting an urban culture, the ‘citizens’ reinvented themselves as a new group.

Around 100 BCE, the court official, Sima Qian, concocted a revised

version of history to please his imperial master. He traced the origin of his

emperor’s Han dynasty back to ‘ancient times,’ making sure to obscure its

heterogenous roots. Sima Qian was a propagandist as much as a

historian and a remarkably successful one. The tale he wove is still recycled

two millennia later.1

The Han state began

to disintegrate around 184 CE with the beginning of an uprising by the ‘Yellow

Turbans’ religious sect.

The fighting, and the

famine that ensued, killed almost 90 percent of the population, reducing it

from 50 million to just 5 million. The remnants of the last Han state then fled

south to the Yangtze Valley. More migrants from North Asia then filled the land

it had left behind. They created a new northern state with a new,

‘northernized,’ form of language. This north-south divide lasted for around 200

years until, in 589 CE, the northern Sui state, founded by the Xianbei people of

central Asia, defeated the southerners.

The Sui were overthrown by what became the Tang Dynasty in

618. They, too, were part of Xianbei descent.

That empire began to fragment in the ninth century and finally collapsed in

907. Several smaller rival states took its place, and the following century was

characterized by upheaval and war with the northern area once again ruled by

Turkic peoples. The Shatuo were replaced by

the Khitan (from whom we get the archaic

name for China: Cathay), who founded the Liao Dynasty until they were conquered

by the Jurchen, who ruled until 1234. None of these people saw themselves as

ruling Zhong Guo. They were Inner Asians for whom China was an imperial

appendage. Beijing became the Jurchens’ winter capital, away from Siberia's

extreme cold, and doubled as an administrative capital for their subject

people. This period is almost entirely glossed over in the ‘national history’

narrative, which prefers to concentrate on a rival state's existence, under the

Song Dynasty, which controlled the southern part of what is now China, although

its territory steadily shrank under pressure from the north.

The Mongols took

Beijing in 1215 before extinguishing the Jurchen Jin Dynasty in 1234.

Over the following half-century, the Mongols pushed ever further south,

squeezing the Song state right back to the coast before finishing it off in a

naval battle near Guangdong in 1279. The Mongols named their Chinese

administration the ‘Yuan Dynasty’ to make it more culturally acceptable, but it

was not a ‘Chinese’ state so much as an Inner Asian great-state. Although

Kublai Khan moved his capital to Beijing in 1271, ‘China’ was simply one part

of a khanate that, in 1279, stretched from the Korean peninsula to the

Hungarian plains.

This united Mongol

realm lasted just less than a century before local insurrection pulled it

apart. A great-state based upon continuous expansion was unable to cope with

the demands of settled administration. The early fourteenth century was a time

of centrifugal chaos, and in several places, local warlords claimed the mantle

of pre-existing empires. Zhu Yuanzhang established a new southern capital (nan-jing) in Nanjing and declared himself the leader of a new

dynasty, the Ming (meaning ‘brilliant’), in 1368. Although ‘national history’

writers portrayed the Ming as an authentically Chinese dynasty, they played

down how much the Ming rulers consciously emulated the Mongols. Indeed, their

government's basic bureaucratic structure, with a Secretariat, Censorate, and

Bureau of Military Affairs, was borrowed from Kublai Khan’s court.

The same was true of

the regional government. The Mongols had parceled out the country

into personal fiefs: each locality leader was the tribal chief who had

conquered it. The Ming copied the principle, but when their scholars came to

write the previous dynasty's history, they erased the details and made the

system sound more centrally organized. In the interests of the Ming

scholar-officials to present themselves as the core of a Confucian state the

real authority lay with the ‘military aristocracy’ – the descendants of the

generals who had supported Zhu Yuanzhang. This,

again, was a pattern directly borrowed from the Mongols. The Ming organized the

population along Mongol lines, too. Military families were organized as

‘centuries,’ who were grouped into ‘thousands’ and then into ‘guards.’

Surviving census registers indicate that the leaders of the ‘guards’ were

generally of Mongol heritage.

The second Ming

emperor did not build a northern capital (bei-jing)

in Beijing because he preferred the climate there. The location – at the

gateway to Mongolia – was deliberate and strategic. He wished to be both

emperors of the Ming and khan of the Mongols. By assuming the Yuan's mantle,

the Ming also extended their control into two areas that had been conquered by

the Mongols: the old Tai kingdom of Yunnan and the Korean-populated Liao River

basin. In Liang Qichao’s version of history, the invading northerners had been

‘civilized’ and ‘Sinicised’ by the superior culture

of the Hua people that they encountered in the Zhong Guo. The Ming's basic

structure (and later the Qing) states tell us that culture flowed both ways.

The Hua were hybrids.

For the Ming, the

‘natural boundaries’ of the great-state stretched from Yunnan's mountains,

northwards and eastwards through the mountains of Sichuan, the Altun, the

Min, and Qilian ranges before joining the less natural frontier of the Great

Wall. These boundaries were specifically designed to keep out Tibetans, Turks,

Mongols, and Manchus – physically but also psychologically. These boundaries

lasted for 300 years until the Manchu Qing breached the wall in 1644. As heirs

to the Khitan, Jurchen, and Mongol

civilizations, Zhongguo was only a waypoint

on the road to regional supremacy. Qing military campaigns would triple the

amount of territory ruled by Beijing. If the Mongols created China, as

nationalist Chinese historian/politician

Liang Qichao asserted, the Manchus created ‘greater China’.

Once we understand

the ‘messiness’ of these twenty centuries, we can see that it takes

considerable imagination, of the kind that can only be provided by nationalism,

to discern within them an essential ‘Chinese’ nation that endured throughout.

At best, this version of history is only an account of several urban

populations who recognized an emperor and wrote with a particular set of

characters.

As Tim Barrett,

professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London has argued,

‘The urge to reconstruct could incorporate without strain considerable

intellectual innovation.’2 He notes how the writing of ‘histories’ during each

time period involved considerable manipulation of evidence to present a version

of the past accorded with the needs of the present. The invention of paper and

scissors allowed for narratives to be cut and pasted at will. In this, the

current work of the National Qing Dynasty History Compilation Committee is

entirely within precedent. Its job is to edit and re-present the previous

dynasty's history to legitimize the current regime and delegitimize its critics

through allegations of ‘historical nihilism.’

Just a year after its

victory in the civil war, the Communist Party leadership called on its

university to write a history of the Qing Dynasty.3 As one of the leading

American historians of the Qing period, Pamela Kyle Crossley, has pointed out,

the instruction would ‘complete the traditional arc in which each imperial

dynasty declared its legitimacy by writing the history of its predecessor.’4

The party’s directive led to the Institute of Qing History's formal creation in

1978 and then, in 2002, to something far bigger. Following a proposal from

Professor Li Wenhai, formerly the president of

Renmin University – and also the secretary of its Communist Party Committee,

director of the China Society of History and director of the History Teaching

Guidance Committee of the Ministry of Education – the State Council approved

the establishment of the ‘National Qing Dynasty History Compilation Committee.’

The project enjoys the kind of government financial support that makes other

historians weep with envy. It has now digitized nearly 2 million pages, and

images translated tens of thousands of foreign studies into Chinese, published

multi-volume collections of documents, and held dozens of academic

conferences.5

From the outset, the Qing Dynasty

History Compilation Committee has been a vehicle for the Communist Party to

direct how the Qing Dynasty is remembered. Following Xi Jinping’s ascent to the

apex of power in 2012, however, the party’s hand has gripped ever more tightly

around the project’s throat. There are increasingly strict limits on what can,

and more importantly, cannot be said about the seventeenth, eighteenth, and

nineteenth centuries. The reason is obvious: facing demands for independence in Taiwan and separatist feelings in Tibet

and Xinjiang, nothing can be allowed to upset the official national narrative

that these places were smoothly, peacefully, and organically incorporated into

the motherland and that they are therefore integral parts of a nation-state

with ancient roots.

Since 2013 foreign

historians such as Crossley, Evelyn Rawski, James Millward,

Mark Elliott, and many others who told a different story about the Qing

Great-State – that it was a Manchu dynasty and

expanded its realm through conquest, violence, and oppression – have been

denigrated in China, denounced as imperialists and denied access to archives.

The same fight has also been taken to independent-minded Chinese historians. In

early 2019 the Communist Party’s own ‘Chinese History Research Committee’

warned that, ‘A minimal number of scholars lack the proper vigilance against

Western academic thoughts, and introduce theoretical variants of foreign

historical nihilism into the field of Qing historical research.’ The phrase

‘historical nihilism’ has become increasingly common in recent years: Communist

Party-speak for research does not support the party’s view of history. The

article, by Zhou Qun, deputy editor of the committee’s journal, Lishi yanjiu (‘Historical

Research’), was republished in the People’s Daily to make sure the message was

widely received. The headline ‘Firmly Grasp the Right of Discourse of the

History of the Qing Dynasty,’ helpfully reminded readers that, ‘Studying

history, and learning from history is a valuable experience of the Chinese

nation for 5,000 years, and it is also an important magic weapon for the

Chinese Communist Party to lead the Chinese people to win one victory after

another.’6.

Another example is

the Chinese Ministry of Education agency charged with promoting the Chinese

language and culture worldwide. Generously backed by government

resources, Hanban now directs more than 500

‘Confucius Institutes’ in over 140 countries worldwide.7 The institutes' work

is mostly focused on language learning, but a particular view on history and

culture is also part of the package. The only book on history that Hanban recommends to its students is entitled Common

Knowledge About Chinese History. Together with its companion volumes about

geography, the series is available in at least twelve languages: from English

to Norwegian to Mongolian. This is the official ‘national history’ – guoshi – packaged up for consumption by foreigners.

And the history that the Confucius Institute chooses to tell still follows the

model laid down by Liang Qichao, albeit with a few communists. The theme of the

first half of the book is China's primordial existence and a people called the

Chinese who have existed across millennia. Even when it wasn’t called ‘China’

or was divided between rival states, it was still somehow ‘China.’ The

underlying premise is continuity. We are told, ‘Many institutions initiated in

the Qin and Han dynasties [over 2,000 years ago] were inherited continuously by

later dynasties.’ The three centuries from the end of the Tang state in 907 to

the arrival of the Mongols in 1260 are described as a ‘chaotic period,’ but

‘China’ was there throughout. When the Mongols invade China, they miraculously become

a Chinese dynasty: ‘In 1279...China has unified into one nation once again.’

Even more ridiculously, the Qing Dynasty's founders are described as ‘Manchu

tribes of northeast China,’ and their takeover is not even acknowledged to be

an invasion.8

The book’s biases are

particularly pronounced when, on rare occasions, it is obliged to deal with

‘non-Han’ peoples, especially when they invade and rule ‘China.’ The Xianbei people, who founded the Wei state across what

is now northern China and Mongolia, apparently discovered that, ‘The key to

consolidating their ruling was to...learn from the Han people.’ We’re told how

the Tibetans used to live in tents but admired the Tang Dynasty culture. They

received the gifts of Chinese culture through their emperor’s marriage to

Princess Wencheng. Liang Qichao’s concept of ‘assimilative power’ is still

going strong. Unless they learn from the Han or fight against them, the other

peoples of northeast Asia are generally absent from the book, as they are from

national history.

Of course, many more

history books are published in China and many historians with a far more

sophisticated understanding of the past. But this book is the one chosen by the

Chinese government to represent its national history abroad. Its narrative is

found in Chinese school books and forms the foundation of Chinese leaders’

frequent references to historical precedents. This is the narrative to which

organizations such as the Institute of Qing History are working. Since Xi

Jinping's coming to power, the political space for dissenting views on history

– never large to begin with – has been shrunk even further. National history is

reduced to a story about the expansion of a superior culture over its

inferiors.

Not surprisingly, the

Confucius Institutes became heavily involved in anti-Hong Kong protests where

they were trying to intimidate, including when a pro-Beijing demonstrator

attacked an ABC reporter.

China's new

nationalism as exemplified by Confucius Institutes is the particular view of

language ethnicity, and history endorsed by the Chinese leadership, which sees

the history of China from the mid-nineteenth century to the Communists’ coming

to power in 1949 as an endless series of humiliations at the hands of foreign

powers.

The Language Wars

A year after the

handover, the Hong Kong government decided that the official mainland version

of Chinese, Putonghua, would become a compulsory subject for primary and

junior-secondary schoolchildren. However, it was taught as a ‘foreign’

language, with perhaps just an hour of class time per week. Ten years later,

the city authorities began to incentivize schools to make Putonghua the

language of instruction. From 2008, schools were given extra funding if they

agreed to teach all their subjects through Putonghua. Increasingly, Hong Kong

parents started to choose these schools for their children, expecting that

Putonghua's fluency would help them obtain better jobs. This seems to have

amplified the generation gap between parents and their offspring, with younger

Hong Kongers resenting having to learn in

Putonghua. For some, it seems to have had the opposite effect to the one

intended: setting them on a path towards resistance rather than integration

with the mainland as particularly seen this past year.

At around the same

time, fears for the future of Cantonese also emerged on the mainland. The city

of Guangzhou (the ‘Canton’ in ‘Cantonese’) was due to host the Asian Games in

November 2010. In July of that year, the city committee of the Chinese People’s

Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC – the body that brings together the

Communist Party and other local organizations in a ‘united front’) recommended

that the province’s main television stations should change their broadcasting

from Cantonese to Putonghua in time for the games.

On 25 July, the

protests moved offline, into the real streets of Guangzhou. At least 2,000

people (some say as many as 10,000) gathered outside Jiangnanxi metro

station to voice their anger. Another protest involving hundreds of people was

held a week later in the city’s People’s Park, and a solidarity rally was held

in Hong Kong at the same time.9 A pan-Cantonese movement appeared to be taking

shape. In response, the Guangzhou authorities backpedaled. The television

station rejected the committee’s Putonghua proposal. The channel was kept off

the satellite network, and the athletes and spectators of the Asian Games were

obliged to receive their news in Cantonese.

It was only a

tactical retreat, however. On 30 June 2014, Guangzhou TV’s hourly news bulletin

switched from Cantonese to Putonghua.10.

In April 2017, the

Chinese Ministry of Education and its agency, known in English as the State

Language Commission11 (officially the National Committee for Language and

Script Work),12 set a target for 80 percent of the PRC’s citizens to speak

Putonghua by 2020. It was absurd: the chances of reaching 140 million people to

speak a new language in three years were minimal, but it was an indication of

the urgency with which the Communist Party views the work of nation-building.

Way back in 1982, a new clause had been inserted into the national constitution

mandating the state to ‘promote the nationwide use of Putonghua.’ More than a

quarter of a century later, the Ministry of Education’s announcement was an

admission that the change had had little effect: almost a third of the

population, around 400 million people, did not speak the national language. As

Hong Kong and Guangzhou (not to mention the far more serious resistance in

Tibet and Xinjiang) demonstrate, the idea of a national language has not been

nationally welcomed.

Also, in May 2018, an

article written by a Chinese University consultant, Song Xinqiao, on the implementation of Mandarin education in

Hong Kong and uploaded onto the website of the Education Bureau reignited a firestorm on the status of Cantonese as

the mother tongue of Cantonese people in Hong Kong. In his article, Professor

Song argued that “mother tongue” should be defined as the language of the Han

(Chinese) race. By that token, the mother tongue of the Chinese people,

including Cantonese in Hong Kong, should be Hanyu, taught in modern China

as Mandarin, but also known as Putonghua in Hong Kong.

Song’s thesis was

premised on his vision of a hierarchy of languages in China, with Mandarin, the

lingua franca, at the pinnacle and superior to all dialects.

This view runs

counter to linguists’ definition of “language.” Under their definition, Cantonese

would be regarded as a separate language because it is not mutually

intelligible with Mandarin or other dialects of China. However, while

technically justifiable, such a view would no doubt be deemed unacceptable by

those cagey about the advocacy of Hong Kong as a separate political entity.

Similar to what

happened with the aborted effort in Guangzhou to launch a Mandarin promotion

campaign, Song’s nationalist model reopened old wounds about the rising

dominance of Mandarin in Hong Kong. At the root of the resentment lies

deep-seated fears about the displacement of Cantonese – both the language and

the people – by the mighty mainland.

In both Shanghai and

Guangzhou, it was also regional prosperity that created the problems for

national language policy. Both became economically strong and, therefore, able

to assert a degree of autonomy from the central government. Simultaneously,

both attracted large numbers of migrants from other parts of the country,

unable to speak the local topolect. The central government urged the cities to

integrate the new arrivals through Putonghua's promotion, thereby

simultaneously integrating the city with the nation. However, in both cities,

this created a backlash among local people resentful at the loss of regional

distinctiveness. This caused local authorities to take steps to protect

regional identity, bringing the city governments into collision with national

instructions.

China’s national

language policy appears to be simultaneously succeeding and failing. While

Putonghua is the national language of schooling, and the number of people able

to speak it is rising, the policy also seems to be provoking rearguard efforts

to defend the regional topolects. The battle is increasingly taking place in

life areas that the central government finds it difficult to control,

particularly the Internet. Online fora buzz with discussions about local

identity and migrants' problems in a cat-and-mouse game with the regulators. In

Shanghai in the 2010s, some local topolect speakers referred to incomers as

‘YPs,’ ying pan, meaning ‘hard disk.’ The largest local producer of

computer hard disks was a company called West Data and the initials ‘WD’

indicated the word wai di, meaning

‘non-local.’13 In response to examples like these, in 2014, the official

communications regulator, the State Administration of Press, Publications,

Radio, Film, and Television, issued a formal ban on puns and wordplay in broadcasts.

It, too, was mocked, and enforcement was minimal.14

Cantonese speakers

have become experts in avoiding the censors. They can use the Cantonese phrase

for ‘northern guy’ as a sound-alike for ‘northern profiteer.’ If they want to

criticize the Communist Party, they can use the phrase ‘grass mud horse’ – cao ni ma, which sounds

like ‘fuck your mother’ in Cantonese. Since the party is often described as the

‘mother’ of the people, the phrase also suggests ‘fuck the party.’ If they want

to criticize party propaganda, they might sarcastically use the Cantonese pronunciation

of the name of a patriotic TV series, ‘Bravo, My Country’ – lai hoi liu, ngo dik gwok – which was itself derived from a phrase used by

communist organizations on social media, ‘Bravo, my brother’ – li hai le, wo de ge. It

looks as though the outlook for the topolects will depend on how economically

important they are. There are plenty of Shanghainese and Cantonese speakers who

have sufficient resources – financial and political – to organize a defense.

However, not all regional ways of speaking will so easily resist the march of

Putonghua. The coming to power of Xi Jinping and his ‘Chinese Dream’ of

national unity suggests that the impetus to impose the national language across

the country will continue. The China State Language Commission sees a direct

connection between its work and the official call for ‘the great rejuvenation

of the Chinese people.’ In its ‘Outline of the National Medium and Long-Term

Plan for Language and Script Reform and Development (2012–2020)’, the

Commission asserted, ‘The comprehensive establishment of a moderately

prosperous society, the construction of a common spiritual home for the Chinese

people, the enhancement of the country’s cultural soft power, and the

acceleration of the modernization of education all put forward new requirements

for the language and script enterprise.’14

This seems to

encapsulate the twin urges that have been driving the reformers’ efforts to

construct a single national language over the course of more than a century.

One desires to make the state more effective and its people stronger through a

language that promotes literacy among the masses and communication between

diverse communities. The other is the nationalistic desire to construct a

‘common spiritual home.’ Buried deep within the language project is the fear

that China might be too diverse to hold together. This is a fear with deep

roots, yet it remains too sensitive to be spoken out loud. We can only hear its

echoes when Xi and his fellow leaders talk about the need for a ‘culturally

harmonious country’ and constantly call for ‘unity.’ Disharmony and disunity

are the concerns-who-must-not-be-named. The idea that Hong Kong or Taiwan – or

Guangzhou or Shanghai – might have their own identities stronger than their

Chinese national identity is literally unimaginable for those who lead the

People’s Republic.

Re-writing Chinese

History, Nation, Language, and Territory, makes it easier to get around the

fact that the Communists had inherited an empire and have been desperate not

only to hold onto it but strengthen their grip on the non-Han regions in a way

which the non-Han Manchus had not found necessary. The focus on Han identity,

on genes and lineage, also explains why China acts as though entitled to assume

that “overseas Chinese” whatever their nationality owe a degree of allegiance

to the “motherland” whether they want to or not.

The party and state

however remain insecure as they attempt to re-write history which was apparent

in 2014 German Chancellor Merkel

presented to President Xi an 18th-century German map of China based on

a famous 1718 Qing “Overview of the Imperial realm.” It only showed

“Sinae Propriae” (China Proper) not the other

Qing territories, or Taiwan. State media reported the gift of a map but instead

pictured an 1844 British map which included the whole Qing empire. Such have

been the almost childish efforts of Beijing to change the record of history,

nation, language, and territory.

The Globe that Was Not To Be

Tuesday 26 March 2019

was a proud day for the director and staff of the London School of Economics. A

new sculpture by the Turner Prize-winning artist Mark Wallinger was being

unveiled right outside the recently completed student center. Wallinger’s work

was entitled The World Turned Upside Down, a literal description of the piece.

It featured a globe, about four meters high, resting on the North Pole, with

Antarctica nearest the sky. The title was a reference to England’s

seventeenth-century Civil War, and the upending of an old order.

In Wallinger’s words: ‘This is the world, as we know it from a

different viewpoint. Familiar, strange, and subject to change.’ Wallinger’s work

has often addressed nationalism. His 2001 commission at the Venice Biennale,

Oxymoron, included British flags with the usual red, white and blue replaced by

the green, white and orange of the Irish tricolor. The LSE’s director, Minouche Shafik, told journalists covering the launch

of the globe sculpture that the work reflected the mission of academia, where

research and teaching ‘often means seeing the world from different and

unfamiliar points of view’.

But one group of

students was not prepared to see the world from a different point of

view. Within hours of the unveiling, a few students from the

People’s Republic of China noticed that Taiwan had been colored pink while the

PRC had been colored yellow and that Taipei had been marked with a red square,

indicating a national capital, rather than the black dot used for provincial

cities. They protested to the director and demanded that the work be changed.

In their view, the artist’s intent was irrelevant: Taiwan should be just as

yellow as the mainland. The LSE was facing a ‘Gap moment’. Students from the

PRC make up 13 percent of the total student body at the LSE,85 so a boycott

could have been ruinous. At the same time, the school’s Taiwanese students and

their supporters also rallied. They pointed out that Taiwan’s president, Tsai

Ing-wen, was a graduate of the LSE, a fact that had been trumpeted by the

school when she was elected. Two days later, the artwork had expanded to

include a notice stating, ‘The LSE is committed to . . . ensuring that everyone

in our community is treated with equal dignity and respect.’15

A crisis meeting was

called, chaired by Shafik and including representatives from the

school’s Directorate, Internal Communication Office and Faith Centre, plus two

Chinese students, one Taiwanese, as well as an Israeli and a Palestinian (who were

upset about the depiction of the Middle East). The Chinese students then tried

to broaden the discussion, saying they were also upset about the depiction of

the Chinese-Indian border. According to the Taiwanese student

present, Shafik apparently ‘took out her notebook’ at this point.87

Wallinger himself

avoided media comment except for one interview with the LSE student newspaper,

The Beaver, in which he said, ‘There are a lot of contested regions in the

world, that’s just a fact.’ The arguments continued for several months until,

in July 2019, the LSE and Wallinger made a minor concession. They added an

asterisk next to the name ‘Rep. China (Taiwan)’ on the work and also a sign

below it stating ‘There are many disputed borders and the artist has indicated

some of these with an asterisk.’88 But Taiwan remained a separate color: the

LSE and the artist held their nerve. They did not ‘do a Gap’ and the sculpture

continues to represent political reality rather than an idealized version of

‘maximum China’ imagined by its patriots online and offline.

Borders and formally

defined territories are a modern, European invention imposed on, and adopted

by, Asian elites over the course of a violent century. The new Chinese

nationalism that emerged from the ruins of the Qing Empire manifested itself as

a desire to be a ‘normal country’, equal to the industrial powers and part of

an international system. The nationalists made a choice without really

realizing they had done so. By choosing to exert a Chinese claim over a

multi-ethnic domain, a decision predicated upon a new Han chauvinism, they

obliged the Republic to extend its reach into the furthest, most marginal

regions. This was, in effect, new colonialism: expanding ‘Han’ Chinese rule

into places it had never reached before. The geographers’ maps and surveys led

the way and their textbooks and national humiliation maps built support for the

project back in the heartland. The geographers and the Guomindang worked

together to make the imaginary boundaries real and create a 'national

territory' a lingtu ( 領土 ), both

on the ground and in the minds of the citizens. They did so by generating a

fear of loss, of humiliation, that continues to animate Chinese policy to this

day.

The Republic of China only formally

recognized the independence of Mongolia under the terms of the 1946 Sino-Soviet

Treaty of Friendship and following a referendum in which the Mongolians

nominally exercised their right of self-determination. The border between China

and Russia, ostensibly agreed in 1689 with the Treaty of Nerchinsk, was only finally settled on 14 October 2008 with

a deal on islands in the Amur River. The border between Guangxi province and

Vietnam, although agreed in 1894, was only formally demarcated in 2009. Tibet

was forcibly incorporated into the People’s Republic of China in 1950, bringing

a Chinese state face-to-face with India for the first time. As the T-shirt

buyers of Niagara Falls know well, the continuing lack of agreement in the

Himalayas can provoke a full-scale war between two nuclear-armed militaries.

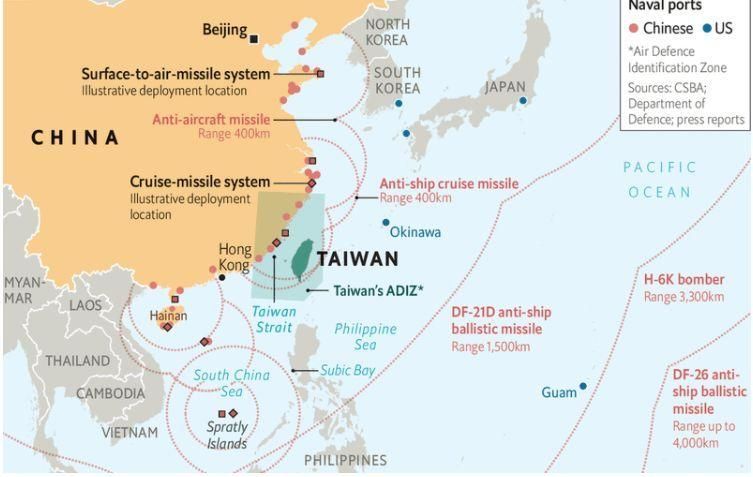

Taiwan’s separateness is an ongoing crisis. And then there are the maritime

boundaries.

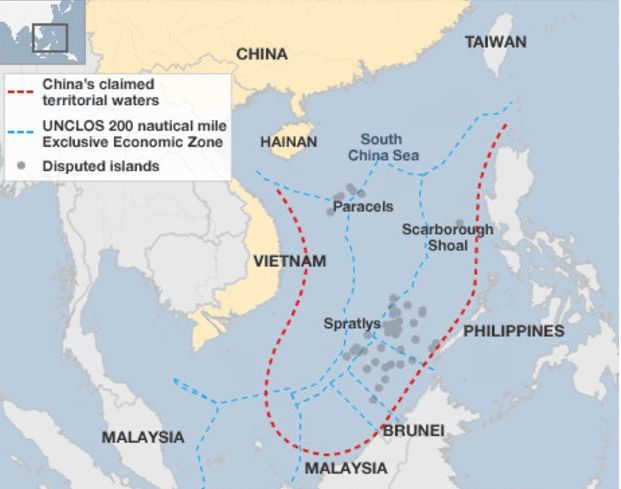

The Reinvention of the South China Sea

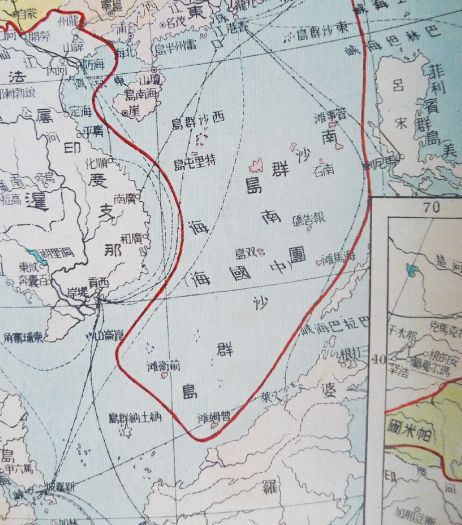

Underneath the map of the South China

Sea was drawn by Bai Meichu (who probably never went to sea in his life)

for his New Atlas of China’s Construction in 1936. James Shoal (off Borneo),

Vanguard Bank (off Vietnam), and Seahorse Shoal (off the Philippines) are drawn

as islands, yet in reality, they are underwater features. Almost none of the

islands that Bai drew in the central and southern parts of the South China Sea

actually:

The ‘Land and

Water Maps Review Committee could not undertake its surveys, however. Instead,

it undertook a table-top exercise: analyzing maps produced by others and

forming a consensus about names.

When it came to the South China Sea, it

is clear from the committee’s conclusions that its leading references were British,

which had far-reaching consequences. On 21 December 1934, the Review Committee

held its twenty-fifth meeting and agreed on Chinese names for 132 South China

Sea features. All of them were translations or transliterations of the names

marked on British maps. For example, in the Paracels, Antelope Reef

became Lingyang jiao, and Money Island

became Jinyin dao (金銀島 Jīn yín Dǎo) – both direct

translations.

1. Naomi Standen (ed.), Demystifying China:

New Understandings of Chinese History, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield,

2013.

2. Tim Barrett,

‘Chinese History as a Constructed Continuity: The Work of Rao Zongyi’, in Peter Lambert and Björn Weiler (eds),

How the Past was Used: Historical Cultures, c. 750–2000, Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2017, chapter 11.

3.

http://www.iqh.net.cn/english/Classlist.asp?column_id=65&column_cat_id=37

4. Pamela Kyle

Crossley, ‘Xi’s China Is Steamrolling Its Own History’, ForeignPolicy.com, 29

January 2019.

5. Zhou Ailian and Hu Zhongliang,

‘The Project of Organizing the Qing Archives’, Chinese Studies in History, 43/2

(2009), pp. 73–84.

6.‘Firmly Grasp the

Right of Discourse of the History of the Qing Dynasty’, People’s Daily, 14

January 2019, http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2019/0114/c1003-30524940.html

(accessed 2 March 2020).

7. Xinhua, ‘Over 500

Confucius Institutes Founded in 142 Countries, Regions’, China Daily, 7 October

2017, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2017-10/07/content_32950016.htm

8. Office of the

Chinese Language Council International, Common Knowledge About Chinese History,

Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2006, pp. 123, 138.

9. Verna Yu and SCMP

Reporter, ‘Hundreds Defy Orders Not to Rally in Defence of

Cantonese’, South China Morning Post, 2 August 2010,

https://www.scmp.com/article/721128/hundreds-defy-orders-not-rally-defence-cantonese

10. Rona Y. Ji,

‘Preserving Cantonese Television & Film in Guangdong: Language as Cultural

Heritage in South China’s Bidialectal Landscape’, Inquiries Journal, 8/12

(2016),

http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1506/3/preserving-cantonese-television-and-film-in-guangdong-language-as-cultural-heritage-in-south-chinas-bidialectal-landscape

11. Xinhua,

‘China to Increase Mandarin Speaking Rate to 80%’, 3 April 2017,

http://english.gov.cn/state_council/ministries/2017/04/03/content_281475615766970.htm

12. Minglang Zhou and Hongkai Sun

(eds), Language Policy in the People’s Republic of China: Theory and Practice

Since 1949, Boston; London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004, p. 30.

13. Qing Shao, Xuesong (Andy) Gao, Protecting language or promoting

dis-citizenship? A poststructural policy

analysis of the Shanghainese Heritage Project, International Journal of

Bilingual Education and Bilingualism Volume 22, 2019 - Issue 3: Controversies

of bilingual education in China.

14. David Moser, A

Billion Voices: China's Search for a Common Language, 2016, p. 90.

15. CNA,

‘Lúndūn zhèng jīng xuéyuàn gōnggòng yìshù jiāng bǎ táiwān huà wéi zhōngguó wàijiāo bù kàngyì’,

7 April 2019, https://www.cna.com.tw/news/firstnews/201904040021.aspx

For updates click hompage here