By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

The Meaning Of China’s Dangerous Decline

The Washington Post

reported China’s

period as a driver of oil growth is near its end. Apparent domestic oil

demand hasn’t appreciably expanded since hitting a plateau in early

2021. This year's rise in consumption went into exports of products from the

country’s refineries and factories.

The worst part is

that the last two months have been among the most momentous in recent Chinese

history. First came the 20th Party Congress, which President Xi Jinping used to

extirpate his remaining rivals. Then, a few weeks later, the country erupted in

the most widespread protests China has witnessed since the mass demonstrations

in Tiananmen Square and elsewhere in 1989. And then, barely a week later, came

the startling denouement. In a rare (if unacknowledged) concession, Beijing

announced it was loosening some of the zero-COVID policies that had driven

so many angry people into the streets.

It has been a

head-spinning season, even by the turbulent standards of contemporary China.

But underneath the noise, the events all carried the same signal: far from a

rising behemoth, as the U.S. media and American leaders often portray it, China

is teetering on the edge of a cliff. Ten years of President Xi Jinping’s

“reforms” widely characterized in the West as successful power plays—have made

the country frail and brittle, exacerbating its underlying problems while

giving rise to new ones. Although a growing number of Western

analysts—including Michael Beckley, Jude Blanchette, Hal Brands, Robert Kaplan,

Susan Shirk, and Fareed Zakaria—have begun to highlight this reality, many

American commentators and most politicians (ranging from former Secretary of

State Mike Pompeo to President Joe Biden), still frame the U.S.-China

contest in terms of Beijing’s ascent. And if they acknowledge China’s mounting

crises, they often cast them as either neutral or positive developments for the

United States.

But the opposite is

true. Far from good news, a weak, stagnant, or collapsing China would be even

more dangerous than a thriving one—not just for the country itself but for the

world. Dealing with a failing China could therefore prove harder for the United

States than coping with the alternative has been. If Washington hopes to do so

successfully—or at least fend off the worst fallout—it needs to reorient its

focus.

Washington’s record

in dealing with declining rivals is not auspicious, and coming up with a new

policy to manage China’s descent will not be easy. To make matters worse, it is

unclear whether the Biden administration has begun working on the problem. But

that is no reason for despair. There are several changes; some relatively

straightforward, the United States could make that would significantly improve

its odds—especially if it starts making them soon.

The Emperor’s Bad Clothes

For many years

following the death of Mao Zedong, China was the world’s exceptional autocracy:

the only large authoritarian state that seemed to defy the laws of political

and economic gravity. Starting in the late 1970s under Mao’s successor, Deng

Xiaoping, China gradually opened its markets, distributed executive power,

imposed internal checks, promoted internal debate, used data to make decisions,

rewarded officials for good results, and pursued a generally non-threatening

foreign policy. These reforms allowed the country to avoid the dismal fate

suffered by most repressive regimes—including the famine and instability China

experienced during Mao’s long reign. Under Deng and his successors Jiang Zemin

and Hu Jintao, China did not just dodge such problems; it thrived, growing its

economy by an average of almost ten percent a year between 1978 and 2014 and

lifting some 800 million people out of poverty (among many other

accomplishments).

Since taking office

in 2012, however, Xi, in his single-minded pursuit of personal power, has

systematically dismantled just about every reform meant to block the rise of a

new Mao—to prevent what Francis Fukuyama has called the “Bad Emperor”

problem. Unfortunately for China, Xi's targeted reforms were the same ones that

had made it so successful in the intervening period. Over the last ten years,

he has consolidated power in his own hands and eliminated bureaucratic

incentives for truth-telling and achieving successful results, replacing them

with a system that rewards just one thing: loyalty. Meanwhile, he has imposed

draconian new security laws and a high-tech surveillance system, cracked down

on dissent, crushed independent nongovernmental organizations (even those that

align with his policies), cut China off from foreign ideas, and turned the

western territory Xinjiang into a giant concentration camp for Muslim Uyghurs.

And in the past year, he has also launched a war on China’s billionaires,

pummeled its star tech firms, and increased the power and financing of the

country’s inefficient and underperforming state-owned enterprises—starving

private businesses of capital in the process.

The recent party

congress was just the icing on this toxic cake. Xi used the event to humiliate

Hu, his predecessor and the last Chinese leader to have been chosen by Deng. He

also replaced Premier Li Keqiang and stacked the Politburo and its powerful

Standing Committee with loyalist hacks (most of whom have security, not

technocratic, backgrounds). More than a display of China’s grandeur, the event

highlighted its growing flaws. It was Xi’s coronation as China’s latest Bad

Emperor.

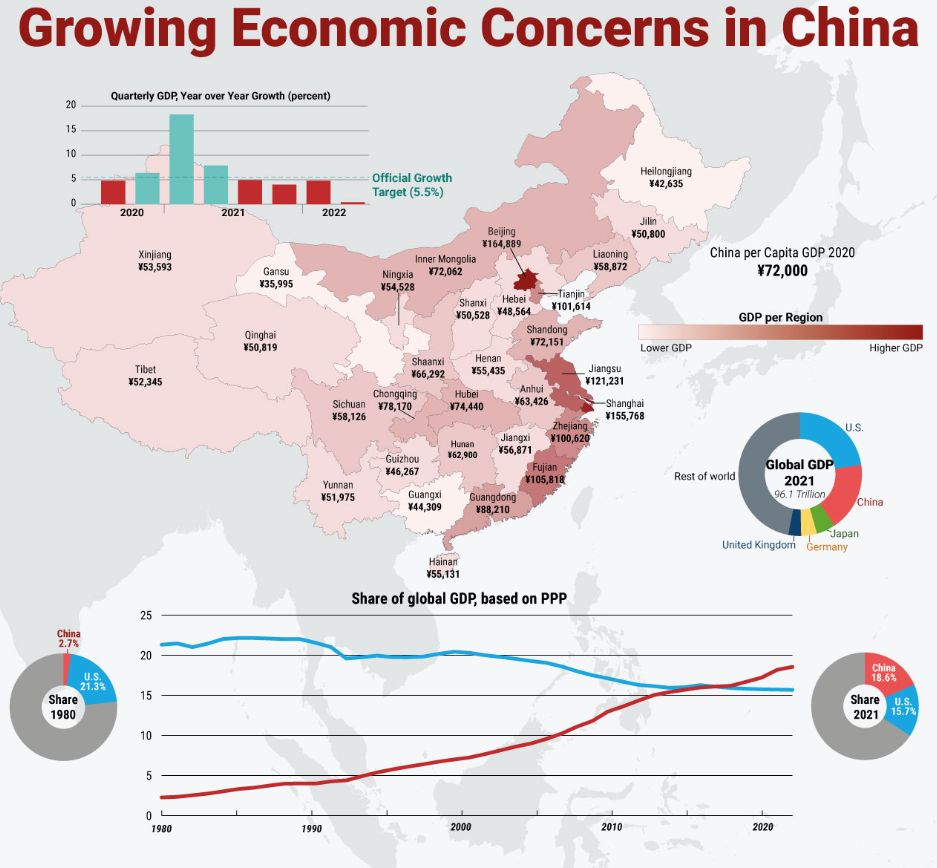

The damage Xi has wreaked

is starting to show in many ways. China’s economy has cratered under his

capricious interference and the weight of zero-COVID (more than 313 million

people were recently under lockdown). The days of 10 percent annual GDP growth

are long gone; while the government projects China will hit 5.5 percent this

year, many analysts think it will be lucky to reach half that figure. The

yuan's value recently hit a 14-year low, and retail sales, corporate profits,

industrial output, and property investment are down. Meanwhile, unemployment

has skyrocketed, hitting 20 percent among young people over the summer. An

estimated 4.4 million small businesses were forced to shutter last year, and

informal data (official statistics are not available) show the country is also

suffering a massive brain drain as tech lords, other billionaires, and

middle-class professionals rush for the exits.

And things are likely

to get much worse. As China stalls, it is increasingly unlikely to overtake the

United States as the world’s largest economy. Instead, with innovation and

entrepreneurship stifled and productivity declining, China will find itself

mired in the middle-income trap. Domestic living standards may flatline or

fall. And smaller budgets and bureaucratic incompetence will make it harder for

Beijing to deal with its many dangerous preexisting conditions: a rapidly aging

population, a massive debt load, a severe shortage of natural resources

(including energy and clean water), and a wildly overheated real estate sector,

the failure of which could pull down the entire economy. (Chinese households

have more than two-thirds of their savings invested in property.)

As the situation

worsens and the promised “Chinese Dream” recedes, widespread anger will likely

continue to bubble over, as it did last month. Few China scholars predict a

full-blown revolution; Beijing’s machinery of repression seems too practical

for that. But dissent among China’s ruling class is more plausible, as Cai Xia,

a former professor at the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party,

has warned. It is true that Xi has removed most rivals and proved a superlative

bureaucratic knife-fighter thus far. But his purges have punished and

humiliated as many as five million officials. That is a lot of enemies for any

ruler—even the most ruthless—to manage.

As he tries to do so,

Xi will face external problems on just about every front—again, most of his own

making. Having abandoned Deng’s dictum that China “hide its strength and bide

its time,” he sought confrontation instead. That has meant accelerating land

grabs in the South and East China Seas, threatening Taiwan, using usurious

loans tendered under the Belt and Road Initiative to grab control of foreign

infrastructure, encouraging China’s envoys to engage in bullying “wolf-warrior”

diplomacy, and most recently, backing Russia in its illegal and unpopular war

on Ukraine. The consequences have been predictable: around the world, Beijing’s

public standing has fallen to near- or all-time lows, while states on China’s

periphery have poured money into their militaries, crowded under Washington’s

security umbrella, and embraced new security pacts such as the Quadrilateral

Security Dialogue (which links Australia, India, Japan, and the United States)

and AUKUS (a trilateral security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom,

and the United States).

In the years ahead,

China’s problems will continue to mount—and to make matters worse. They will

probably catch Xi by surprise since, under his totalitarian system, lower-ranked

officials are now punished for sending bad news up the chain. As Shirk, a

former U.S. deputy assistant secretary of state and the author of Overreach:

How China Derailed Its Peaceful Rise, puts it: “People won’t dare tell [Xi] the

actual downsides and costs of his policies and the problems they’re creating.”

Even vital government-to-government communications no longer get through, which

sharply increases the risk of an accidental conflict. As Matthew Pottinger, a

top China adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump, recently explained, “We came

to the determination during the Trump Administration that messages we sent

through diplomatic channels were not reaching Xi. The Biden

Administration has come to a similar conclusion.”

Careful What You Wish For

American hawks will

be tempted to celebrate China’s struggles. But they should postpone the party,

for a declining China could be much more dangerous than a booming one. Given

U.S.-Chinese interdependence, a weaker Chinese economy—especially one burdened

by the inevitable tsunami of infections as Beijing relaxes its COVID rules—will

mean a more fragile U.S. economy. (Consider the global problems Apple recently

suffered when Foxconn’s Zhengzhou complex erupted in labor

disputes.) Although some scholars posit that China tends to turn

inward when struggling with issues at home, a decline can and has had the

opposite effect on other countries, making them more unpredictable and

belligerent. Brands, for example, has pointed to Germany in the runup to World

War I and to Japan’s decision to attack the United States in World War II to

argue that “peril may emerge when a country that has been rising, eagerly

anticipating its moment in the sun, peaks and begins to decline before its

interests have been fulfilled.”

The risks are

especially significant when that country’s leader has staked his prestige on

big promises he feels he must deliver, just as Xi has done. Increasingly anxious

to bolster his credibility—especially after the public failure and embarrassing

reversal of his zero-COVID policy—and unable to rely on economic growth for his

legitimacy (as previous Chinese leaders have), he may turn to the other arrow

in the dictator’s quiver: nationalism. If he does, the result will be a China

that looks and acts more like a supersized North Korea: a cash-strapped,

repressive regime that provokes and threatens its adversaries to extract

concessions, burnish its pride, and distract its public.

The greatest danger,

of course, would be a military move on Taiwan. The parallels between Russian

President Vladimir Putin and his calamitous war on Ukraine are chilling. As

Blanchette has written, “an environment in which an all-powerful leader with a

single-minded focus cannot hear uncomfortable truths is a recipe for disaster.”

Yet that is just the kind of system that Xi has created.

Stay Humble

A U.S.-China policy

that accounted for all these dangers would require several shifts in

Washington’s current approach. First, the United States should do everything

possible to ensure its model is as attractive. As a failing China becomes less

and less enticing to other countries, the United States must polish up its

appeal. An excellent way to start would be to address U.S. political

dysfunction. But at the moment, the prospects of doing so, and restoring trust

in American institutions, seem dim.

A more achievable

goal would be to avoid responding to Chinese provocations in ways that betray

American values. As the political scientist and former Biden administration

official Jessica Chen Weiss argues, by doing things such as blocking Chinese

media access and restricting Chinese visas, “the United States has drifted

further from the principles of openness and nondiscrimination that have long

been a comparative advantage.”

On a related note,

U.S. politicians should quit antagonizing China for narrow domestic political

purposes. Hinting that Washington seeks regime change in Beijing, as Trump

aides did on numerous occasions, accomplished little more than increasing

China’s insecurity. The same can be said for purely symbolic and inflammatory

gestures such as then–House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan in August.

The more

nationalistic Beijing becomes, the harder Xi may try to pick a fight—so the

United States should avoid giving him any extra ammunition. The tricky thing,

of course, is that poking the dragon is a long-standing American tradition for

a reason: it plays well at home. Changing this approach will not be easy,

especially as the United States heads into a presidential election. But

avoiding gratuitous provocation is not a sign of weakness or the same thing as

appeasement. To make that clear, Washington should visibly enhance its ability

to contain a flailing China, articulate clear redlines, and end the policy of

“strategic ambiguity” on Taiwan (as the political scientist Richard Haass and others have advocated) while also reemphasizing

that Washington would oppose any Taiwanese moves toward independence. The United

States should send these latter messages quietly, however—in direct talks with

Taipei and Beijing—to avoid issuing a public challenge to which Xi feels

compelled to respond. To further shift his calculus, Washington should also

bolster U.S. military assets in areas of possible confrontation, such as the

Western Pacific. It should do all it can to make Taiwan a more challenging

target (a long-overdue project is finally underway).

Of course, sending

subtle messages requires a means to do so. So the Biden administration should

reestablish a robust channel for crisis communications and reengage with China

diplomatically in a way the United States has avoided chiefly for the last six

years—not to reward China for bad behavior, but to make sure the two governments

can talk when they need to.

Regarding the

economy, the Biden administration deserves some credit for recent moves such as

passing the CHIPS and Science Act and establishing export controls that will

limit China’s access to semiconductors and the materials needed. These steps

should reduce the United States’ economic and strategic dependence and slow

China’s military advancement without provoking it excessively. But Washington

should think harder about the tradeoffs involved in continuing to decouple.

Although such moves might help further insulate the U.S. economy, they arguably

promote protectionism and could create problems for U.S. foreign policy by

reducing Washington’s leverage and decreasing Beijing’s incentives to

cooperate.

The difficulties in

striking the right balance point to a final principle: as Washington reorients

its China policy, it must be modest in two important senses. First, if and when

China starts visibly deteriorating, the United States must avoid the

triumphalism that accompanied the fall of the Soviet Union (despite President

George H. W. Bush’s efforts to avoid humiliating the Soviet leader Mikhail

Gorbachev). Publicly dunking on a struggling rival may be tempting, but it will

serve no one’s interests. Despite their understandable eagerness to score

points at home, American politicians must remember that as China declines, Xi’s

political incentives to pick fights may grow—but so will his material

incentives to cooperate since Beijing will have much less money and attention

to use for solving problems. Washington still needs Beijing’s cooperation on

various issues, such as fighting climate change and preventing future

pandemics. It should make that cooperation as easy for Xi as possible. That

means toning down the gratuitous tough talk. And, as Shirk suggests, it means

giving “Xi reason to believe that if he were to moderate his policies, the

United States would notice, acknowledge it, and reciprocate in ways that would

be good for China.”

The second form of

modesty involves remembering just how hard a problem a failing China will

present—and how badly the United States has dealt with such cases. Consider the

U.S. record on North Korea. Washington has indeed managed to prevent the

worst-case scenarios: although there have been plenty of threats, a few minor

skirmishes, and a lot of missile tests, the Kim dynasty has refrained from

starting an actual war with anyone since 1950. But Washington has

simultaneously failed to stop Pyongyang from immiserating its people; exporting

illegal narcotics, counterfeit dollars, and weapons; and, most importantly,

developing a substantial nuclear arsenal. That is not for lack of trying; U.S.

presidents, going back to Bill Clinton, have spent vast amounts of time and

effort attempting to avoid these outcomes. But they have all failed—which says

something important about the difficulty of the challenge. Now, remember that

the population of China is about 54 times larger than that of North Korea and

that China’s GDP is almost a thousand times more significant, and the scale of

the problem comes into focus. Managing China’s decline will be a long,

complicated process with painful tradeoffs; in truth, there probably is no way

to fully insulate the United States and the rest of the world from the pain it will

inflict. But that is all the more why policymakers should focus on it now.

For updates click hompage here