By Eric Vandenbroeck and

co-workers

China's global ambitions

While we earlier

mentioned that arctic geopolitics may also further heat the already warming

northern cone and that Russia is deploying armored

icebreakers and nuclear submarines to assert its territorial claims as

mineral deposits are discovered to this can be added that China has been doing

similarly.

With a staff of over

200 academic and non-academic workers, China’s Polar Research Institute

established a China-Nordic Arctic Research Center in Shanghai in 2013 to

promote collaborative research between nine Nordic and eight Chinese research

universities and institutes. The center’s broader mission is revealed in its

statement of purpose, which includes an effort to “promote cooperation for the

sustainable development of the Nordic Arctic and a coherent development of

China in a global context.” 1 China also constructed a research station on

Svalbard, a satellite receiving station in Kirkenes, Norway, a second research

center in Iceland, and a third in Finland.2 It jumpstarted its ability to

undertake independent research in the Arctic by purchasing an icebreaker from

Ukraine in 1994. Named Xuelong, or “Snow Dragon,” the

icebreaker enables China to pursue research in the Arctic and Antarctica. China

brought its own domestically built icebreaker – Xuelong

2 – online in 2019, as pictured below.

Based on a Finnish

design, it is operated by the Polar Research Institute. As a result, China is a

leader in Arctic expeditions, having undertaken nine to the Arctic and 28 to

Antarctica. And experts believe that China is on its way to building a powerful

nuclear-powered heavy icebreaker; only Russia currently possesses such a

capacity.3

China’s Arctic

interests extend well beyond science-related concerns. A growing strategic

interest in the region mirrors the country’s broader global ambition in the

wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. In 2009, the Polar Research Institute

set up an Arctic strategic research department to provide policy support for

the Chinese leadership on geopolitical issues around the region.4

In discussing China’s

interests in the Arctic, the editors of the Journal of the Ocean University of

China wrote, “Preparedness ensures success, while unpreparedness spells

failure. Only with the development of forward-looking, in-depth research can

[China] possess the right to speak up about future international affairs

pertaining to the polar regions.” 5

President Xi

Jinping's push for China to establish an economic foothold in the Arctic has

translated into a significant investment. This investment is considered

part of China’s Polar Silk Road, and its Silk Road Fund. In fact, Chinese

companies invested in 65 Swedish companies between 2002 and 2019, including

companies with dual-use technology such as lasers and semiconductors.6 In

response, Sweden announced plans in 2020 to tighten its FDI rules.

Denmark, too, balked

at three high-profile Chinese economic initiatives: first, when a Chinese firm

attempted to buy a defunct US base in Greenland, which would have provided

Beijing with a significant new base for intelligence activities in the Arctic; 7

second when the Chinese ambassador made a trade deal with Denmark’s

self-governing Faroe Islands contingent on an agreement to sign a 5G contract

with Huawei;8 and, third when Beijing attempted to build two airports in

Greenland. In its 2019 risk assessment, the Danish Defense Intelligence Service

identified Chinese large-scale resource investments in Greenland as a risk

given the potential for “political interference and pressure” when “investments

in strategic resources” are involved.9

Xi Jinping’s

conception of Chinese security also includes a dramatic transformation in the

position and role of the US military on the global stage.

As pointed out before

underpinning the dynamics of rising tensions, military assertiveness,

negotiation, and confrontation in the South China Sea is the diplomatic and

military presence of the United States.

For almost two

decades since the signing of the Declaration on a Code of Conduct in 2002,

ASEAN has attempted to negotiate a South China Sea Code of Conduct with China.

In 2018, it developed a negotiating text for the code of conduct, but many of

the critical issues, such as the geographical range, the nature of the dispute

resolution process, bans on further land reclamation, and the right of outside

actors such as the United States to hold military exercises, have not been

resolved.10

Singapore’s

ambassador-at-large Bilahari Kausikan has accused

China of only superficially engaging with ASEAN, saying that Beijing is

negotiating in a “barely convincing way.” He notes that “progress has been

glacial” and that Chinese diplomats often hold the negotiations hostage until

ASEAN adopts positions with which it agrees.11

After the Philippines

also Malaysia attempted to adopt a more active stance in pushing back against

China’s expansive claims. In December 2019, it submitted its own claim to the

United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to establish

the outer limits of Malaysia’s shelf beyond the 200 nautical mile limit,

overlapping with waters claimed by China.12

The Malaysian auditor

general revealed the Chinese PLA Navy and coast guard ships had undertaken 89

incursions into Malaysia maritime waters between 2016 and 2019.13 And in the

spring of 2020, Chinese and Malaysian vessels had an extended standoff in their

disputed territory.14 China’s military assertiveness has further triggered

rising arms expenditure throughout the region. Overall military spending by

ASEAN increased 33 percent between 2009 and 2018.15

The United States

historically has taken no sides in the South China Sea dispute, although it has

stepped in at various times to support sovereignty rights under UNCLOS and

freedom of navigation.

Among Chinese

scholars, there is diminishing tolerance for what they believe to be US

provocations in China’s backyard. CICIR researcher Lou Chunhao,

for example, argues that “The South China Sea issue fundamentally is about

China and other regional countries’ territorial and maritime claims…. China has

an important role in the South China Sea because it is a regional power…. China

and ASEAN countries are after all the owners of the South China Sea region.” 16

The message is clear: the United States should step back and accept China’s

interests and new geopolitical realities. Or in common parlance: the United

States should pack its bags and head back across

the Pacific.

Similarly, on October

6, 2020, the German Ambassador to the United Nations read a statement on behalf

of 39 countries stating that they were “gravely concerned” about China’s

policies toward both Hong Kong and Xinjiang.17

In a speech

commemorating the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the Shenzhen Special

Economic Zone in October 2020, Xi referred to the “new practice” of one

country, two systems, stressing the need for Shenzhen to lead in the

development of Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao to “strengthen their [young

people from Hong Kong and Macao] sense of belonging to the motherland.”18

Commentators began discussing how Shenzhen’s “transformation from a backwater

into a hi-tech metropolis” could “point the way forward for Hong Kong.”19 At

the same time, Hong Kong authorities were busy sentencing the young democracy

activists, such as Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow, to jail. As the businesspeople

had predicted, Hong Kong was well on its way to becoming just another mainland

city.

The notion of

sovereignty and the unification of China is at the heart of Xi’s ambition to

realize the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Even before assuming

leadership of the CCP and the country, Xi stressed the importance of China’s

sovereignty claims and core interests. During his visit to the United States as

vice president of China in February 2012, he noted that if the United States

could not respect China’s “major interests and core concerns,” particularly

around Taiwan, the relationship would “be in trouble.”20

And in a January 2019

speech commemorating the 40th anniversary of former Chinese leader Deng

Xiaoping’s “Message to Compatriots in Taiwan,” he made his intentions clear:

The historical and

legal fact that Taiwan is part of China and the two sides across Taiwan Straits

belong to same China can never be altered by anyone or any force…. We make no

promise to renounce the use of force and reserve the option of taking all necessary

means…. This does not target compatriots in Taiwan, but the interference of

external forces and the minimal number of “Taiwan independence” separatists and

their activities…. Taiwan independence goes against the trend of history and

will lead to a dead end. Taiwan must be unified, will be unified with China.21

Unification, Xi asserted, was “a historical conclusion drawn over the 70 years

of the development of cross-Strait relations, and a must for the great

rejuvenation of the Chinese nation in the new era.”22

President Tsai has responded

to Beijing’s deployment of both sharp and hard power by reducing Taiwan’s

reliance on China and expanding its ties with outside actors.

Beijing, for its

part, has not relented but only increased the stridency of its rhetoric and

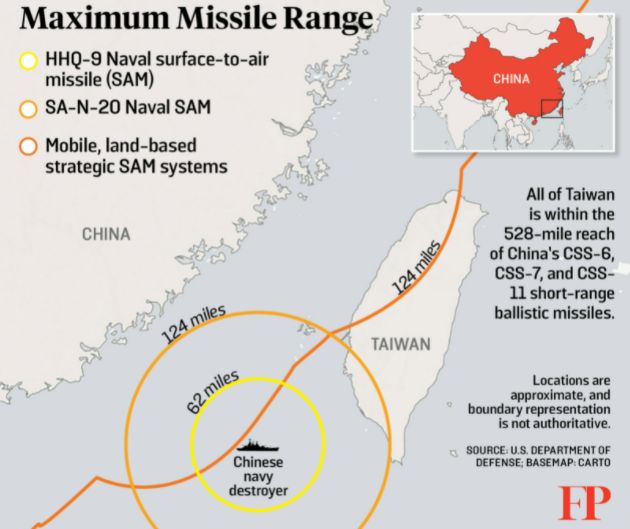

threatening actions. In September 2020, Chinese warplanes crossed the median

line of the Taiwan Strait forty times in two days. And on October 10, the PLA

undertook a large-scale, multi-force exercise that simulated a successful

invasion of Taiwan. CCTV and the nationalist Global Times also aired a video

version with stirring music.23

China claims the

legal rights around sovereignty stipulated in UNCLOS, such as the Exclusive

Economic Zone and continental shelf, as well as historical rights within its

nine-dash line.24 To bolster its assertions of historical rights, Beijing cites

Chinese references to the Spratlys dating back to the

Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). Based on a collection of maps from the Qing

Dynasty, China’s Foreign Ministry also claims that China held administrative

jurisdiction over the Spratlys during the Qing and

has produced an 1868 “Guide to the South China Sea” that reports on Chinese

fishermen in the Nansha (Spratly) islands: “The footmarks of fishermen could be

found in every isle of the Nansha Islands and some of the fishermen would even

live there for a long period of time.”25

Every claimant,

however, has its own South China Sea sovereignty story. For example, Tran Duc

Anh Son, a well-known Vietnamese historian, asserts that the Nguyen Dynasty

(1802–1945) exerted clear sovereignty over the Paracels – even planting trees

to warn against shipwrecks. And there is evidence in history books around the

world that a Nguyen-era Vietnamese explorer placed the country’s flag on the

Paracels in the 1850s.26 Son also discovered a set of maps from the 1700s at

the Harvard-Yenching Library that demonstrates that

the Qing Dynasty laid no claim to either of the island chains and considered

Hainan Island the southernmost part of the country.27 In

addition to historical ties, Vietnam rests its claims on a 1933 legal

annexation document issued by France, which represented a lawful method of

territorial acquisition at the time. When Vietnam achieved independence from

France, the latter’s territorial rights in the Paracels devolved first to South

Vietnam and later to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.28

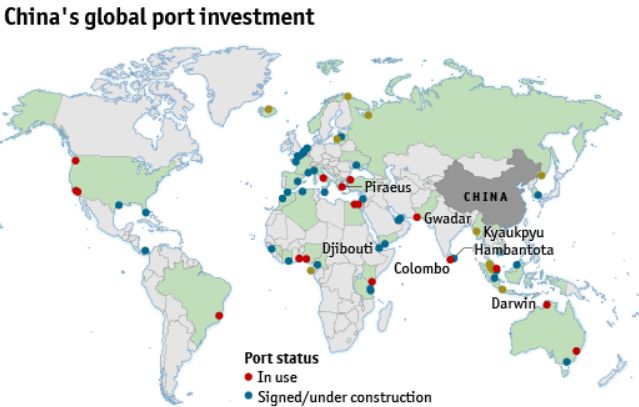

Once its first Djibouti base was in operation, some

experts at the PLA Naval Command College stated that the construction of

overseas bases would likely provide the “most effective strategic assistance”

to China’s armed forces in “going out.” And they further noted that it was “an

inevitable choice to realize the dream of a great power and the dream of

building a powerful military.”29

Beijing is indeed on a

port-buying spree. China owns or has a stake in nearly two-thirds of the

world’s 50 largest ports.30 Asia security scholar Mohan Malik has detailed

Beijing’s moves to acquire long-term leases on strategic ports, including

Pakistan’s Gwadar port for 40 years, Greece’s Piraeus port for 35 years,

Djibouti’s port for ten years, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port for 99 years, 20

percent of Cambodia’s total coastline for 99 years, and the Maldivian island of

Feydhoo Finolhu for 50

years.31 In addition, Beijing is pressuring Myanmar to raise China’s stake in

the Kyaukpyu port on the Bay of Bengal from 50

percent to 75–85 percent and to lease it for 99 years, as well in exchange for

Myanmar avoiding a $3 billion penalty for reneging on the Myitsone dam deal.

One of the most overt

statements of PRC intentions is voiced by three analysts at the PLA’s Institute

of Military Transportation, who penned an essay in which they argued: “To

protect our ever-growing overseas interests, we will progressively establish in

Pakistan, United Arab Emirates, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Singapore, Indonesia,

Kenya, and other countries.

a logistical network

based on various means, buying, renting, cooperating, to construct our overseas

bases or overseas protection hubs.”32 Chinese objectives are a mix of

political, economic, and military, including war, diplomatic signaling,

political change, building relationships, and providing facilities for

training.33 This logistical network will be supported by and, in turn, support

the PLA’s ability to launch and sustain overseas missions.34 Cambodia is also

rumored to be the site of a new Chinese base. Reporting has suggested that

China may already be constructing a naval base under a secret agreement.35

China is developing

advanced weapons, leading U.S. officials to push for the first nuclear talks between

the two countries. Biden administration officials say the issue has taken

on more urgency than has been publicly acknowledged.

Beijing’s recent

moves, such as building new missile silo fields and testing new types of

advanced weapons, suggest China may now be interested in developing a nuclear

first-strike capability, not just the minimum deterrent. Biden raised the

possibility of “strategic stability talks” with Xi Jinping, China’s leader,

during a virtual summit this month.

Conclusion

The objective of

China’s soft, sharp, and even hard power efforts is to

shape the political and economic choices of foreign actors in support of

Beijing’s values and interests. China wants to prevent companies from

identifying Taiwan as a separate entity, universities from inviting the Dalai

Lama, and film studios from portraying China in a negative light. As Singapore’s

former Ministry of Foreign Affairs permanent secretary Bilahari Kausikan cleverly notes, “China doesn’t just want you to

comply with its wishes, it wants you to think in such a way that you will, of

your own volition, do what it wants without being told.”36

At the same time, the

strong hand of the state often undermines Beijing’s soft power initiatives or

transforms them into sharp power equivalents. China’s use of personal

protective equipment as a cudgel to pressure countries to express gratitude

to China during the pandemic resulted in significant negative coverage by

international media and falling levels of international public approval. In the

case of TikTok, the CCP mandate that companies turn over any information the

government requests diminishes the founder’s ability to operate in major

markets and advance China’s soft power ambitions. Similarly, the CCP’s use of

CIs to promote political views and activities on issues such as Taiwan and

Tibet has dimmed their prospects in many countries, turning them into objects

of suspicion as opposed to celebrations of Chinese language and culture.

President Xi’s

determination to use China’s provision of personal protective equipment (PPE)

to the rest of the world to control the narrative around the pandemic, coerce

thanks, and bolster CCP legitimacy, for example, caused Beijing’s international

standing to plummet and countries to begin considering how to move their supply

chains out of China. What began as a diplomatic triumph transformed into a

diplomatic debacle.

Importantly, China’s

use of soft, sharp, and hard power resonates differently in different contexts.

Efforts to “tell a positive story” about China through Chinese media or to

deploy CIs are better received in countries where access to a broader range of

media and other outlets is more limited. Similarly, with regard to sharp power,

most countries withstand Chinese pressure to compromise on issues of core

national security or principle, whereas individual private actors are more

vulnerable to Chinese coercion and more likely to seek compromise. Beijing’s

displays of hard power in Asia have also undermined its soft power potential,

contributing to high levels of popular distrust in China. For African and Latin

American countries, however, military concerns are far less significant.

Surprisingly, perhaps, Chinese trade and even investment do not correlate

strongly with overall trust and favorability. A broader set of foreign policy

and human rights concerns play a more dominant role. Despite Xi Jinping’s stated

desire to improve China’s image, he demonstrates little inclination to modify

Chinese behavior. It is a choice that Chinese public opinion polls appear to

support. in June 2021, Xi called for the creation of a more credible and

“loveable” Chinese image, suggesting a rhetorical shift may be underway.37

Chinese leaders have

historically placed a high priority on sovereignty. The narrative of loss and humiliation dating back to the Qing Dynasty is deeply embedded

in the country’s political culture, as is the desire to realize long-held

territorial claims, whether legally justified or not. While all Chinese leaders

since Mao have called for China to realize its sovereignty claims, Xi Jinping

has made unification a central condition of his vision of the great

rejuvenation of the Chinese nation; and his statements display a strong sense

of inevitability and urgency around the realization of Chinese claims,

particularly with regard to Taiwan. An important subtext to Xi’s reunification

campaign is his effort to promote a China model that other countries might

emulate. The specter of millions of Hong Kong citizens protesting for democracy

and the clear commitment by Taiwan’s citizens to their democratic process cast

doubt on the credibility of a China model. Moreover, the defeat of pro-Beijing

candidates in both Hong Kong and Taiwan’s elections represents a very public

repudiation of Xi’s narrative within territories that Beijing claims as its

own. Xi’s claim that there is something uniquely

Chinese about the path he has set out for mainland China is also undermined by

Hong Kong, prior to the National Security Act, and Taiwan.

China’s strategy for

realizing its sovereignty claims displays elements of soft, sharp, and hard

power. With regard to Hong Kong and Taiwan, it

demonstrates a high degree of tolerance for the separation of systems and

international space for Taiwan as long as it feels confident that its diplomacy

is resulting in greater integration. When, however, it perceives that a

preponderance of political voices is advocating greater separation from the

mainland and that forces within Hong Kong and Taiwan that supported

reunification are weakening, it quickly adopts sharp and hard power tactics.

This is particularly evident in the case of Taiwan, where Beijing immediately

rolled back the diplomatic and economic wins it had permitted Taiwan under the

Ma government as soon as President Tsai

Ing-wen indicated that she would not support the ’92 Consensus. And it

introduced a range of sharp power tactics, including reducing the number of

Chinese tourists and students and meddling in the mid-term elections. It also

has used military action with increasing frequency to discourage Taiwan from

taking further action to enhance its independent status.

Similarly, in the

South China Sea, although it maintains a process of ongoing diplomatic

negotiation, China has expanded both its capability and its willingness to

deploy military power. And when other claimants challenge its sovereignty

claims, it will respond with coercive economic tools. Only when the claimants

accede to Chinese terms will Beijing ease its economic coercion. For example,

when the Philippines temporarily dropped its efforts to enforce the decision of

the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, Beijing ended its ban on the

import of Philippine bananas and indicated a willingness to increase its

imports of a wide range of additional goods. Nonetheless, the Philippine

efforts to placate Beijing yielded no accommodation on the actual issue of

sovereignty claims.

China also frames its

sovereignty quest in the context of US-China relations. The United States is

the primary guarantor of regional security and freedom of navigation. It has

strong military allies and partners in the region and maintains a legal commitment

to support Taiwan’s self-defense capabilities. Xi, however, has called

explicitly for Asia to be managed by Asians and for the US system of alliances

to be dismantled. In this context, China has attempted to use the negotiations

over the South China Sea Code of Conduct to prevent the United States from

conducting military exercises there. Moreover, Beijing’s frequent references to

“external forces” as a significant source of unrest and protest in Hong Kong

and Taiwan seek to undermine the credibility of domestically derived democracy

activism by blaming other countries, in particular the United States, for

creating trouble.

China promotes itself

as a supporter of the current rules-based order but routinely ignores

international law in pursuit of its sovereignty claims. Even before the ruling

of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, it declared that it would

not observe the ruling or participate in the arbitral process. In the case of

Hong Kong, China asserted that the Joint Declaration was a historical document

with no practical significance, invalidating its legal standing. Beijing

ignores widespread international criticism over its disregard for international

norms, while successfully rallying countries from Africa and the Middle East to

its defense. As Chinese military capabilities continue to grow, it will likely

move beyond its focus on Taiwan and the South China Sea to more consistently

press its non-core sovereignty claims, such as those against India and Japan.

The BRI is an exquisite manifestation of Xi Jinping’s

dream of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” It positions China

at the center of the international system, with physical, financial, cultural,

technological, and political influence flowing out to the rest of the world. It

redraws the fine details of the world’s map with new railways and bridges,

fiber optic cables and 5G, and ports with the potential for military bases. And

it is a platform for sharing political values through capacity building on

internet governance, safe cities, and media content. China has tried to portray

the BRI as a multilateral arrangement and global initiative. Yet the reality is

something quite different. It is a collection of often opaque bilateral

agreements signed under a Chinese framework notion. The Belt and Road Forums

further enhance the impression of Chinese centrality: heads of state travel to

China to seek deals as supplicants to China. Even groups such as the 17+1

encourage small and middle-sized countries to compete with each other for

Chinese favor rather than to unite around a common negotiating position.

The BRI has the potential

to raise incomes globally and to bring much-needed investment to countries that

otherwise have found it difficult to modernize their infrastructure. Some

countries, such as Pakistan, are being transformed by the BRI, with new energy

projects, roads, railways, a massive upgrading of both its Gwadar port and its

digital infrastructure. The Port of Piraeus has become one of the top ports in

Europe and ranked within the top 50 in the world. Greek officials are

understandably bullish on their BRI investments. Officials in Brazil likewise

view the BRI as an opportunity to partner with China on a wide range of

initiatives, such as infrastructure, innovation, and sustainability. They

express an enthusiasm, as well, for China’s willingness to “listen” to what

countries want and need.

At the same time, BRI

host countries often reflect doubts over the externalities that accompany BRI

funding: opaque deal-making, rising environmental degradation and pollution,

and limited attention to social impact concerns. The lack of transparency in lending

ensures that Beijing retains the advantage in negotiations and facilitates

corruption. Popular protests have proliferated, particularly around hard

infrastructure projects, and new leaders, including those in Malaysia,

Pakistan, and Tanzania, have sought to overturn or renegotiate unfavorable deal

terms. At the same time, the BRI has left other countries, such as Pakistan,

saddled with projects whose returns will likely never equal the initial

investment and seeking additional debt relief from other international lenders.

Many Chinese companies and officials themselves are concerned that a lack of

understanding of host countries’ domestic political and economic situation

results in suboptimal outcomes for BRI projects. Despite Beijing’s pledges to address

these concerns, opinion polls indicate that few countries find China’s efforts

to change course compelling.

Finally, the BRI has

become a significant source of global competition. It has energized other

advanced economies in Europe and Asia, as well as the United States, to develop

their own infrastructure and connectivity projects to compete with Belt and Road.

Australia, India, and the larger European economies have become more attentive

to infrastructure needs in their own backyards. Japan, in particular, provides

alternatives to Chinese BRI investment in Africa and Southeast Asia, where it

has surpassed China as the largest source of infrastructure investment. The

United States views the BRI through the lens of geostrategic competition and

has been a vocal critic of Chinese BRI governance practices and has sought to

persuade other countries not to accept BRI funding. Increasingly, Washington

has focused its energy on the Digital Silk Road, where, China is poised to play

a truly transformative role in creating the infrastructure for the 21st

century.

China’s emergence as

a world-class technology power capable of setting global standards is a top

priority for Xi Jinping and the rest of the Chinese leadership. They have put

in place a suite of policies designed to advance this objective, including a demand-driven

model for R&D; significant financial support for individual firms and

universities as well as startups; the protection of Chinese firms from foreign

competition through programs such as MIC 2025; the acquisition of foreign

talent and technology through both licit and illicit means; alignment between

Chinese government priorities and those of Chinese firms; and pushing Chinese

standards through the BRI and international standard-setting bodies. This

highly centralized and controlled approach has significant benefits in its

ability to link core technology priorities identified in strategic plans such

as MIC 2025 with funding initiatives, talent acquisition, and efforts at

international standard-setting. It has paid off in areas such as 5G, where a Chinese

company such as Huawei has driven technological advances and been recognized as

a world leader. Chinese government policy provided financing and protected the

Chinese market from foreign competition, but the technological advances emerged

from an actor that both innovated and acquired technological know-how and

possessed an intuitive understanding of the market. At the same time, the

Chinese playbook has created problems for Chinese companies as they seek to

expand globally, particularly in advanced market democracies, where there are

broader concerns over national security and Chinese government access to

countries’ information. Xi Jinping’s push to deepen the CCP’s control over

nominally private firms

such as Huawei has contributed to their exclusion from some markets.

Moreover, Beijing’s

political repression

in Xinjiang and Hong Kong has created a context in which Chinese technology

companies are understood as part of a broader Chinese challenge to democratic

norms. To the extent that Chinese technology companies underpin this political

repression by providing surveillance and censorship technologies, it also

impinges on their ability to be treated as separate from the Chinese state and

to expand their global market share. Chinese strategic technology plans, such

as MIC 2025 and Dual Circulation, also seek to decouple Chinese technology

innovation and manufacturing from the international economy in order to develop

and protect an indigenous Chinese technology ecosystem before eventually

recoupling. Critical to this process, however, is the continued acquiescence of

foreign actors to Chinese terms, such as accessing the foreign talent and

foreign technology. The decision of the United States to break the pattern by

investigating IP theft or other abuses by the Thousand Talents Plan and by

placing firms such as Huawei on the Entity List created unforeseen and

challenging disruptions to Beijing’s strategic plans. Even as firms in each

country want access to the other’s market, the degree of technology decoupling

underway will be difficult to arrest given political concerns and the

imperatives of economic and security competition. Moreover, as the following

chapter explores, China is advancing an even broader process of political and

ideological decoupling. It is working to transform the global governance

system, and in particular norms and values around human rights, internet

governance, and economic development, to reflect Chinese values and priorities.

Its vision is one in which China’s state-centered model of political and

economic development is both protected and promulgated.

Xi Jinping’s ambition

for China to lead in reforming the global governance

system is reflected across multiple policy arenas. By shaping the system of

international institutions and arrangements that govern states’ interactions,

China ensures that it has the greatest opportunity to advance its domestic

political, economic, and security interests, to protect itself from

international criticism of its domestic policies around issues such as human

rights, and to prevent Taiwan from expanding its independence and international

space through membership in international organizations. Its global governance

playbook combines both deft diplomacy and brute force. Xi frequently delivers

keynote addresses at major global governance gatherings that elevate China’s

image as a global leader. China also mobilizes significant resources to advance

its interests. It places its officials in leadership positions within the UN

system and other international governmental organizations and deploys large

numbers of experts into the technical bodies of these organizations to advance

Chinese standards and norms.

The sheer number of

Chinese participants and proposals they present shapes the debate in

significant ways. China also uses its financial wherewithal to advance its

interests: for example, by investing in scientific research and research

stations in the Arctic or by providing support to organizations such as

UN DESA. In addition, China has sought to gain support for its positions by

trading votes and offering financial incentives to – or in some cases

threatening economic consequences against – other countries. China’s

participation and efforts to reform international institutions are also often

designed to serve its narrower interests. Beijing requires that Chinese

officials and other Chinese actors in international institutions support

domestic priorities as opposed to fulfilling the mandates of the agencies they

serve. Wu Hongbo, for example, prevented Uyghur World Congress, President Dolkun Isa, from testifying at the United Nations; Lenovo

was pressured to

support the standard put forward by Huawei in the ITU, and Cai Jinyong favored lending to Chinese companies that would not

normally fall within the portfolio of IFC lending. China has also integrated

the BRI into over two dozen international organizations. When the United States

and other countries prevented the BRI from being written into the

reauthorization bill for the UN Mission to Afghanistan, China threatened to

veto the mission. China has made significant strides toward enhancing its

position in global institutions and in reforming norms and values in those

institutions in ways that align them more closely with its own. Increasingly,

however, it faces pushback in its efforts to enhance its economic stakes in the

Arctic, to advance the BRI in the United Nations, and to place its officials in

leadership positions. The greater China’s success in using the global

governance system to advance its own domestic policy preferences, the greater

the resistance from other actors and the more difficult future progress

becomes.

In May, we posted an

article from old to new Great Divergence; more recently, China’s

property-led economic

slowdown shows no Signs of ending.

1. “The evolution of

CNARC: 2013–2018,” China–Nordic Arctic Research Center, December 2018.

2. “China,” Arctic

Institute, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/countries/china/.

3. Laura Zhou,

“China’s new icebreaker Snow Dragon II ready for Antarctica voyage later this

year,” South China Morning Post, July 12, 2019.

4. Linda Jakobson and

Jingchao Peng, “China’s Arctic aspirations,”

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2012.

5. David Curtis

Wright, “The dragon eyes the top of the world,” Naval War College China

Maritime Institute, August 2011.

6. Simon Johnson,

“Sweden to tighten foreign takeover rules amid security worries,” Reuters, May

8, 2020.

7.Auerswald, “China’s

multifaceted Arctic strategy.”

8. “China denies

threatening to pull plug on Faroe Islands’ salmon trade deal over Huawei 5G

contract,” Salmon Business, December 11, 2019.

9. Danish Defence Intelligence Service, Intelligence Risk Assessment

2020, December 2020, 21.

10. Felix K. Chang,

“Uncertain prospects: South China Sea Code of Conduct negotiations,” Foreign

Policy Research Institute, October 6, 2020.

11. “Bilahari Kausikan’s speech on ASEAN & US–China Competition in

Southeast Asia,” Today, March 31, 2016.

12. Laura Zhou,

“Asean members up the ante on South China Sea.”

13. Dzirhan Mahadzir, “China pushes back against US statement

on South China Sea claim, ASEAN stays silent,” USNI News, July 14, 2019.

14. Jason Loh, “South

China Sea: time to display firm resolve,” The ASEAN Post, July 25, 2020.

15. Tony Walker,

“Naval exercises in South China Sea add to growing fractiousness between US and

China,” The Conversation, July 8, 2020.

16. Chunhao Lou, “为何美日澳总是搅局南海问题?

[Why do the United States, Japan, and Australia always disrupt the South China

Sea Issue?]” opinion. china.com.cn, 2017.

17. “Joint Statement

on the Human Rights Situation in Xinjiang and the Recent Developments in Hong

Kong, delivered by Germany on behalf of 39 countries,” United States Mission to

the United Nations, October 6, 2020.

18. “Xi Focus: China

celebrates 40th anniversary of Shenzhen SEZ, embarking on new journey toward

socialist modernization,” Xinhua, October 14, 2019.

19. Ken Chu, “Hong Kong

still has a place in Beijing’s grand reforms after Shenzhen,” South China

Morning Post, October 17, 2020.

20. Xi Jinping, “Vice

President Xi Jinping policy speech, February 15, 2012,” filmed at the National

Committee on US–China Relations, New York.

21. “Highlights of

Xi’s speech at Taiwan message anniversary event,” State Council Information

Office of the People’s Republic of China, January 2, 2019.

22. “Xinhua

Headlines: Xi says ‘China must be, will be reunified’ as key anniversary

marked,” Xinhua, January 2, 2019.

23. “Joint

multidimensional landing drill conducted in sea areas of East and South China

Seas,” YouTube, October 11, 2020,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DPp_Guk3GEc&feature=youtu.be.

24. Mingjiang Li, “Reconciling assertiveness and cooperation?

China’s changing approach to the South China Sea dispute,” Security Challenges

Vol. 6, No. 2 (Winter 2010).

25. “Historical

evidence to support China’s sovereignty over Nansha Islands,” Ministry of

Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, November 17, 2000.

26. Mike Ives, “A

defiant map-hunter stakes Vietnam’s claims in the South China Sea,” New York

Times, November 25, 2017.

27. “Maps question

China’s claims over Vietnamese islands,” Tuoi Tre News, May 30, 2016.

28. Raul Pedrozo,

“China versus Vietnam: an analysis of

29.Masayuki Masuda,

“China as regional actor,” in China Goes to Eurasia, National Institute for

Defense Studies, Japan, November 2019, 19.

30. James Kynge et al. “How China rules the waves,” Financial Times,

January 12, 2017.

31. Mohan Malik,

“Countering China’s maritime ambitions,” Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, March 23,

2020.

32. Tianze Wang, Wenzhe Qi, and Jun Hai, “海外军事基地运输投送保障探讨

[Discussion of transportation and delivery guarantees for military bases],” 国防交通工程与技术

[National Defense Transportation, Engineering, and Technology], No. 1 (2018).

33. Mathieu Duchâtel, “China Trends #2 – Naval bases: from Djibouti to

a global network?” Institut Montaigne, June 26,

2019.

34. Cassandra

Garrison, “China’s military-run space station in Argentina is a ‘black box’,”

Reuters, January 31, 2019.

35. Jeremy Page,

Gordon Lubold, and Rob Taylor, “Deal for naval outpost in Cambodia furthers

China’s quest for military network,” Wall Street Journal, July 22, 2019.

36. Charissa Yong,

“Singaporeans should be aware of China’s ‘influence operations’ to manipulate

them, says retired diplomat Bilahari,” Straits Times, June 27, 2018.

Qi Wang, “Over 70%

respondents believe China’s global image has improved, wolf warrior diplomacy a

necessary gesture: GT poll,” Global Times, December 25, 2020.

37. Stephen

McDonnell, “Xi Jinping calls for more ‘loveable’ image for China in bid to make

new friends,” BBC, June 2, 2021.

For updates click homepage here