By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers 30 Dec. 2018

Chaos At The Asia-Pacific Economic

Cooperation Summit

Drawing headlines all

over the world this years annual Asia-Pacific

Economic Cooperation summit ended in unprecedented chaos and disarray, without

agreement on a joint communique for the first time in its history as the

escalating rivalry between the United States and China dominated proceedings

and reflected escalating trade tensions. Sunday’s dramatic conclusion was

foreshadowed by accusations that Chinese officials had attempted

to strong-arm officials in Papua New Guinea, which was hosting the event,

into issuing a statement that fitted what Beijing wanted. Less noticed were two

short memorandums released on the sidelines of the conference by the island

nations of Vanuatu and Tonga. In return for renegotiating existing debt, both

agreed to become the newest participants – following other Pacific nations like

Papua New Guinea and Fiji – in Chinese

President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign-policy venture, the Belt and Road

Initiative (BRI).

May 2017, President

Xi reminded the 29 foreign heads of state and representatives from more than

130 countries and 70 international organisations that

over 2,000 years ago, "our

ancestors trekking across vast steppes and deserts, opened up the

transcontinental passage connecting Asia, Europe and Africa, known today as the

Silk Road." He went on to refer to the sea routes that later evolved

linking the East with the West, and noted that the ancient silk routes

"opened windows of friendly engagement among nations, adding a splendid

chapter to the history of human progress . . . and embody the spirit of peace

and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual

benefit."

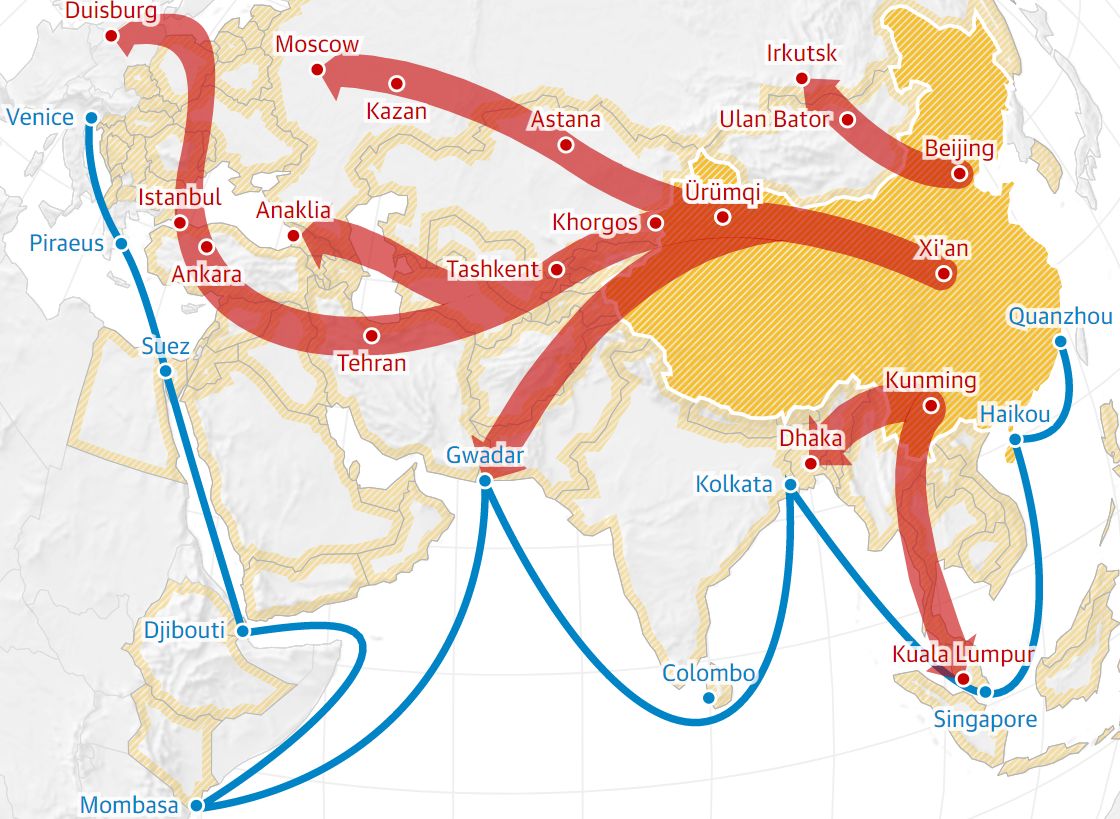

The standard

explanation is that the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime

Silk Road aims

to build a trade and infrastructure network connecting Asia with Europe and

Africa along the ancient trade routes of the Silk Road. Or as an upcoming book is

about to explain, the BRI creates a venue for the meeting of cultures by

promoting people-to-people interaction and exchange. But China’s grand ambition

may

not necessarily be a road to riches for its partners.

Throughout history,

would-be powers have invented new ways of growing. The Mongol Empire connected

lands through trade, the Qing dynasty built a tributary system, the United

Kingdom collected colonies, the Soviet Union created ideologically linked

spheres of influence, and the United States established an institutionalized

order and a global military presence. China, too, has looked for new sources of

power and has used it in ways not previously attempted.

As the analyst Nadège

Rolland has written, the Belt and Road Initiative “is

intended to enable China to better use its growing economic clout to achieve

its ultimate political aims without provoking a countervailing response or a

military conflict.” Many observers have wondered whether the Belt and Road

Initiative will eventually have a military component, but that misses the

point. Even if the initiative is not the prelude to an American-style global

military presence and it probably isn’t – China could still use the economic

and political influence generated by the project to limit the reach of American

power. For instance, it could pressure dependent states in Africa, the Middle

East, and South Asia to deny the U.S. military the right to enter their

airspace or access their ground facilities.

While its inroads

into places

like South Asia are well known, Beijing is also building

its way to European markets by flowing capital in the construction of a network

of infrastructures that will grant the transfer of Chinese goods all over the

Old World.

China’s crude maps

show the belt and road running through disputed territory, including the

bitterly contested waters of the South China Sea where China has been busy

building fortresses on reefs.

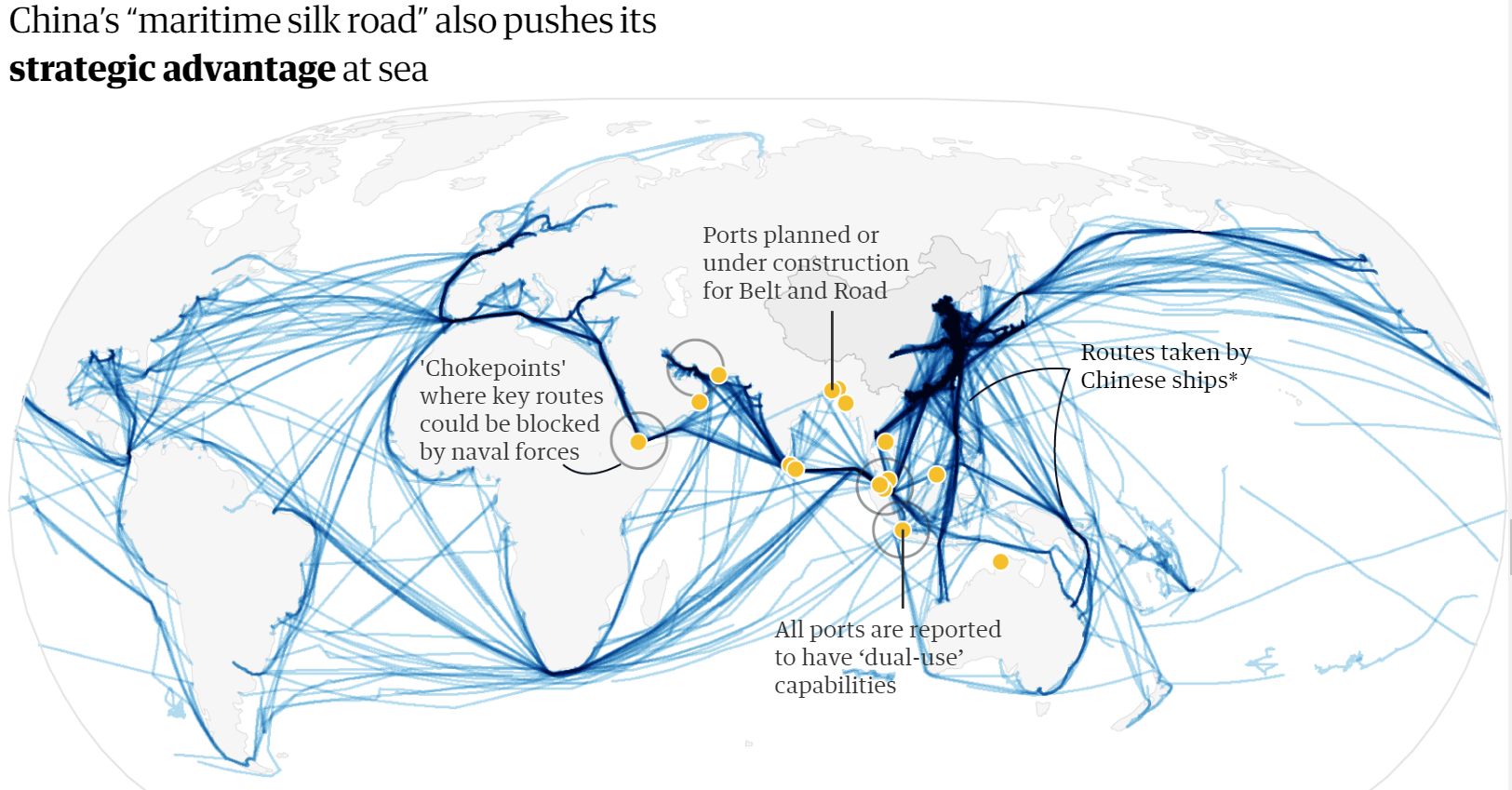

Thus the term itself

is confusing. The “road” refers mostly to a sea route; the “belt” is on

land. The BRI's Maritime Silk Road links

China by sea to Africa and southwest Asia and, via the Suez Canal, Europe. On

the BRI's sea leg, China will help build seaports, improve old ports and port

facilities and improve the ports' regional land transportation infrastructure.

In fact, one can say

that the BRI, as constituted, has

no historical precedence other than in rhetoric. The ambition to encircle

India by land and sea is new. So is the creation of a financial and resource

exchange system for power, transportation and infrastructure development in

central Asia, the Middle East, parts of Europe and Africa. Likewise, the formation

of trade and security relationships designed to keep the US away from Asia, or

at least stifle its reach.

It is also a

never-ending challenge

to evaluate and value the BRI. At the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in May

2017, President Xi

claimed that investment in BRI countries since 2013 had already exceeded $ 50

billion. This, though, was almost certainly a reference only to foreign

direct investment by Chinese companies, including mergers and acquisitions

account for a small proportion of Chinese foreign investment abroad –perhaps no

more than 9–10 per cent on an annual basis – and also a small proportion of the

much larger amounts disbursed via direct project investment, that is, financing

linked specifically to projects. Thus the BRI is like holy writ –never revealed

completely and all at once, but only bit by bit and over many decades.

Politically and

strategically, the BRI raises other important questions. Some think, for

example, that it is primarily a Eurasian development project, in which China,

unusually, is assuming a leadership role in supplying public goods and

improving economic welfare in large tracts of the world economy. Others accept

this but also think that it is a major Chinese economic, foreign policy and

international relations project designed to benefit mainly China. The

distinction is quite important. A Eurasian development project would suggest

that China is taking on a strong leadership role, and pursuing regional and

global objectives to which Beijing would, if necessary, subordinate its

immediate national interests. History offers no assurances that this is likely.

It is true that China’s participation in the Asian Infrastructure Investment

Bank, in which it is the biggest shareholder and has an effective veto, entails

its being willing to subscribe to an internationally accepted governance

structure. Yet, as the core of China’s international relations, it would be

strange if the BRI were not principally a China First strategy.

India who feels

encroached upon suggests

potential BRI participants unwrap the silk camouflage and carefully

consider a Chinese Road project where Beijing is pouring concrete, the

deep-water port of Gawdar in Pakistan's Baluchistan

province (which borders Iran). China is building a huge navy. Gawdar is a perfect base for China's blue water fleet– an

Indian Ocean Chinese base challenging the Indian Navy.

Unlike America’s

financial and global policy thinking at the end of the Second World War,

reflected in the Marshall Plan, the BRI comes with no proposals for a new

international architecture. The BRI provides for no formal institutions with

members or a secretariat drawn from participating countries. There are no

formal commitments to established criteria, designs, financing principles and

safeguards in the implementation and operation of projects. Little or no

attention is paid to corruption, human rights and labor or environmental

standards, and there is no transparency or accountability. The lack of

institutional infrastructure may not matter to commercial and financial

decisions affecting project infrastructure, but it could be a major shortcoming

in relations between China and some of its larger neighbors and other powers.

Another important

factor will also be is that as the Chinese age structure of the population

rises, consumption patterns will change. Households save less, principally

because older, retired citizens receive less income and have to live off or

draw down their savings. Lower household savings mean that unless companies or

the government save more, the rate of investment will come down. Lower

investment and a stagnant or falling working-age population drag downtrend

growth. And as explained before this is going to be

especially relevant to China. Because of lower trend growth, aging

societies could be places where lower inflation and interest rates plant

stronger roots. Or there could be acute skill and labor shortages which push

wages and inflation higher. We don’t know for sure because there is no

template, but we have to be vigilant about both outcomes. There is a new school

of thought that argues that inflation might not pick up because labor shortages

won’t happen thanks to the arrival of robots and artificial intelligence that

could drive millions of people out of work, contributing to chronic

technological unemployment. As a result, we will end up in a low-wage economy

in which poverty and income inequality will become widespread.

Testing the financial returns

Whether Chinese

leaders actually seek a financial return from the Belt and Road Initiative has

increasingly become questionable –the

sovereign debt of 27 BRI countries is regarded as “junk” by the three main

ratings agencies, while another 14 have no rating at all.

Investment decisions

often seem to be driven by geopolitical needs instead of sound financial sense.

In South and

Southeast Asia expensive port development is an excellent case study. A 2016

CSIS report judged that none of the Indian Ocean port projects funded

through the BRI have much hope of financial success. They were likely

prioritized for their geopolitical utility.

Projects less clearly

connected to China’s security needs have more difficulty getting off the

ground: the

research firm RWR Advisory Group notes that 270 BRI infrastructure projects

in the region (or 32 percent of the total value of the whole) have been put on

hold because of problems with practicality or financial viability. There is a

vast gap between what the Chinese have declared they will spend and what they

have actually spent.

Thus China’s plan is

like the curate’s egg. More

and more Chinese projects are running into trouble. According to a study by

RWR Advisory Group, a Washington consulting firm, 234 of a total of 1,674

projects in 66 countries have run into either financial or political trouble in

the past five years. The Centre for Global Development estimates that 23 nations

are facing financial stress. Concerns over poor administration, weak

governance, and Chinese political heavy-handedness are widespread. Two weeks

ago, Mahathir bin Mohamad, the Malaysian prime minister, announced on a visit

to China that he was canceling two Chinese-financed infrastructure projects.

Worth about $23 billion, they were deemed unaffordable and figured in

corruption investigations in Kuala Lumpur, centered on the previous prime

minister. Dr Mahathir spoke, however, about “a

new version of colonialism’” implicating his rather embarrassed hosts.

Pakistan, Nepal,

Bangladesh and Burma are among countries that have cancelled projects because

of financial difficulties or political interference. African countries

especially, gathering in Beijing this week for the Forum on China-Africa

Co-operation, acknowledge China as their biggest trade partner, but some are

uncomfortable about China extracting commodities and profits, running

persistent trade surpluses and providing cheap exports and its own workers,

displacing both local goods and workers. The Bagamayo

port and special economic zone development north of Dar es Salaam is expected

to cost $10 billion, or about a fifth of Tanzania’s GDP.

In Africa, the

Nairobi-Mombasa rail project has accumulated substantial losses within a year

of operation as cargo traffic on this critical route has remained stubbornly on

trucks and lorries.

In Sri Lanka, the

desperately under-utilized Hambantota Port had to be surrendered to Chinese

operators in a humiliating example of debt-trap diplomacy. And Pakistan’s new

Prime Minister Imran Khan has been scathing in his assessment of the US$60

billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – another flagship Belt and

Road project.

A further example why

China’s grand ambition may not necessarily be a road to riches for its

partners; in September of 2018, during a major conference with African leaders,

China's president Xi Jinping proposed

an additional $60 billion in financing for Africa in the forms of

assistance, investment and loans, the western media was quick to label the

latest round of Chinese financing a "debt trap", to which a top

Chinese official responded at the time that Beijing is merely helping Africa

develop, rejecting criticism it is loading African countries with unsustainable

financial burdens.

It turns out, the

official was not exactly telling the truth, because far from handing out free

money the African

Stand reports that China is likely to take over Kenya's lucrative Mombassa port if Kenya Railways Corporation defaults on its

loan from the Exim Bank of China.

Unsustainable debt

will result in appeals for financial assistance, as they have in Pakistan, and

in colonial-type “payment-in-kind” deals, including controlling stakes. Sri

Lanka, for example, spends four fifths of government revenues to service debt

incurred to build an overcapacity in highways,

an international airport, now labelled the “world’s

emptiest airport”, and the desperately under-utilized Hambantota Port had

to be surrendered to Chinese operators in a humiliating example of debt-trap

diplomacy.

A recent article in

the South China Morning Post even went as far as to suggest that "the

Belt and Road has failed."

And Bruno Maçães (author of Belt and Road: A Chinese World Order)

wrote that, the

BRI may well never realize its goals. It may be abandoned as it runs into

problems and the goals it sets out to achieve recede further into the distance.

But success and failure are to be measured in terms of these goals, so we must

start with them.

Update: The potential

weaponization of BRI

For

updates click homepage here