By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Know Your Rival, Know Yourself

Rightsizing the China Challenge

Ever since the United

States ascended to global leadership at the end of World War II, American

leaders have regularly been stricken by bouts of anxiety that the country is in

decline and losing ground to a rival. The Soviet Union’s 1957 launch of the

Sputnik satellite prompted such fears, as did Soviet expansionism in the 1960s.

In the 1980s, Washington was seized by the worry that American industry was

incapable of competing with Japan’s economic juggernaut. Even in 1992, just

after the Soviet Union collapsed, an article in the Harvard Business

Review asked, “Is America in Decline?”

Today, this

perception of decline is wedded to fears about new vulnerabilities in the U.S.

democratic system and the burgeoning strength of China. Both

of these concerns have merit. Although U.S. voters disagree on the

sources of the threats to American democracy, they broadly express an anxiety

that their country’s democratic institutions can no longer deliver on the

American dream’s promises. An October Gallup poll found that three-quarters of

Americans were dissatisfied with their country’s trajectory.

Meanwhile, the story

goes, China is powering ahead, pairing ambitious

economic and diplomatic agendas with a massive military expansion while the

United States staggers under the weight of inequality, stagnating wages,

legislative gridlock, political polarization, and populism. Over the past three

decades, China has indeed established itself as the factory of the world,

dominating global manufacturing and taking the lead in some advanced technology

sectors. In 2023, China produced close to 60 percent of the world’s electric

vehicles, 80 percent of its batteries, and over 95 percent of the wafers used

in solar energy technology. That same year, it added 300 gigawatts of wind and

solar power to its energy grid—seven times more than the United States.

The country also exerts control over much of the mining and refining of

critical minerals essential to the global economy and boasts some of the

world’s most advanced infrastructure, including the largest high-speed rail

network and cutting-edge 5G systems.

As the U.S. defense

industry struggles to meet demand, China is producing

weapons at an unprecedented pace. In the past three years, it has built

over 400 modern fighter jets, developed a new stealth bomber, demonstrated

hypersonic missile capabilities, and doubled its missile stockpile. The

military analyst Seth Jones has estimated that China is now amassing weapons

five to six times faster than the United States.

To some observers,

such advances suggest the Chinese system of government is better suited than

the American one to the twenty-first century’s demands. Chinese leaders often

proclaim that “the East is rising and the West is

declining”; some U.S. leaders now also seem to accept this forecast as

inevitable. Arriving at such a broad conclusion, however, would be a grave

mistake. China’s progress and power are substantial. But it has liabilities on

its balance sheet, too, and without looking at these alongside its assets, it

is impossible to evaluate the United States’ real position. Even the most

formidable geopolitical rivals have hidden vulnerabilities, making it crucial

for leaders to more keenly perceive not only the strengths but also the

weaknesses of their adversaries.

And although China

will continue to be a powerful and influential global player, it is confronting

a growing set of complex challenges that will significantly complicate its

development. Following a decade of slowing growth, China’s economy now contends

with mounting pressures from a turbulent real estate market, surging debt,

constrained local government finances, waning productivity, and a rapidly aging

population, all of which will require Beijing to grapple with difficult

tradeoffs. Abroad, China faces regional military tensions and increasing

scrutiny and pushback by advanced economies. Indeed, some of the foundational

conditions that drove China’s remarkable growth over the past two decades are

unraveling. But just as these new difficulties are emerging, demanding nimble

policymaking, Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power has stifled

political debate and sidelined technocrats, yielding a policymaking process

that is brittle, reactive, and prone to missteps. Chinese young people now lament

the narrowing space they have to achieve their goals,

a trend that won’t change unless their country’s leadership does. But that event appears

distant.

Even with its many

shortcomings and vulnerabilities, the United States continues to command a

strategic depth that China fundamentally lacks: a unique combination of

economic vitality, global military superiority, remarkable human capital, and a

political system designed to promote the correction of errors. The resilient

and adaptable U.S. economy has the world’s deepest and most liquid capital

markets and unparalleled influence over the global financial system. The United

States continues to attract top global talent, including many Chinese nationals

now fleeing their country’s autocratic political environment.

Put plainly, the

United States still has a vital edge over China in terms of economic dynamism,

global influence, and technological innovation. To highlight this fact is

neither triumphalism nor complacency. It is the root of good strategy, because

Washington can easily squander its asymmetric advantages if excessive pessimism

or panic depletes its will, muddies its focus, or leads it to overindulge

nativist and protectionist impulses and close America’s doors to the rest of

the world. For despite its problems, China is still making headway in specific

domains that challenge U.S. national security and prosperity, such as quantum

computing, renewable energy, and electric vehicle production. A

political-economic system such as China’s can remain a fierce rival in key

areas even as it groans under the weight of its pathologies.

China most often

gains primacy in areas in which the United States is dramatically

underinvested. China’s greatest assets in its competition with the United

States are not its underlying fundamentals but its hyperfocus and willingness

to expend enormous resources, and tolerate enormous waste, in the pursuit of

key objectives. That means that Washington cannot afford to retreat from

sectors vital for competing in the twenty-first century’s economy, as it did in

the case of 5G technology in the previous decade.

U.S. President-elect

Donald Trump’s campaign rhetoric relied particularly heavily on the specter of

American decline. The United States does face its own daunting array of

problems abroad and at home, but these pale in comparison to those China faces.

And Washington’s tendency to stress its rivals’ power and underestimate its own

strengths has often backfired, becoming a trap that leads to serious policy

errors. Even Trump’s most pessimistic advisers should understand this

history—and recognize that U.S. leaders risk making costly missteps by adopting

a reactive posture toward China instead of capitalizing on the United States’

comparative advantages to push forward its interests at a moment when Beijing

is struggling.

Confidence Game

Throughout the last century,

the United States has consistently overestimated the strength of its rivals and

underestimated its own. This habit became particularly evident during

the Cold War, when U.S. officials and analysts were consumed by fears that

the Soviet Union had grown superior in military might, technological

advancement, and global political influence. In the late 1950s, for instance,

U.S. officials came to believe that the Soviets had a much larger and more

sophisticated stockpile of intercontinental ballistic missiles. Intelligence

gathered by U-2 spy planes and other sources, however, later revealed that the

so-called missile gap had been mostly imaginary. As the Cold War drew to a close, it became clear that the Soviet economy was

crumbling under the weight of military expenditures, and much of the feared

Soviet superiority was exaggerated or based on misinterpretations.

The tendency to

underappreciate the United States’ strength is driven by a difference in how

democracies and autocracies perceive and present their weaknesses. Democratic

systems are more transparent and foster more debate about their own flaws. This

can lead to a heightened focus on domestic shortcomings, making weaknesses

appear more significant than they are. A democracy’s vulnerabilities can seem

even more alarming when compared with the apparent strength of authoritarian

regimes, which, conversely, punish criticism and disseminate propaganda in order to present a brighter picture than the reality. The Soviet Union strove to maintain a veneer of

invincibility by censoring its press and mounting military parades. Its efforts

to mask its economic stagnation, political infighting, and failure to innovate

often fooled U.S. policymakers; the United States’ tendency toward

self-criticism, meanwhile, obscured its own advantages.

Sometimes, this

dynamic redounds to the United States’ benefit. The prospect of a rival’s

ascendancy can mobilize American resources and political will: for instance,

although the claim that the United States lagged the Soviet Union in its

production of ballistic missiles was largely erroneous, the warning served as a

powerful motivator for the U.S. government to boost its defense spending and

accelerate its technological research. To some extent, the misperception that

the United States was losing its comparative advantage helped it maintain that

advantage. Similarly, the Soviet Union’s early space race victories—and the

fear that the United States would fall behind in a crucial, symbolic

contest—prompted the U.S. government to create NASA, renew its investments in

science education in American schools, and increase funding for scientific

research. In this case, the worry that the Soviet Union was outstripping the

United States was valuable, catalyzing beneficial investments that undergirded

a subsequent half-century of American technological superiority.

Underestimating

geopolitical threats also comes with costs, as it did in the case of Nazi

Germany’s rise in the 1930s, al Qaeda’s growth in the 1990s, and Russian

President Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine The chaos that these underestimates unleashed can make it

seem as if it is generally safer to overestimate the threat posed by a

potential adversary. But in many cases, developing an outsize fear of a rival

has led the United States to misallocate government resources, lose sight of

the need to nurture its sources of strength, become distracted by peripheral

threats, or even become mired in unnecessary wars. The United States’ immense

financial and human investments in the Vietnam War, for example, were inspired

in part by the so-called domino theory, which held that if the United States

allowed Soviet-backed communism to take hold in Southeast Asia, communism would

inexorably come to dominate the globe. That belief led the United States to

fixate on winning a costly, protracted war that ultimately drained its

resources, hurt its reputation worldwide, and eroded Americans’ trust in their

own government. Decades later, a similar mobilization against an exaggerated

threat—Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq—led to a disastrous and drawn-out

conflict, domestic turmoil, and the further decline of the United States’

international credibility.

The United States’

tendency to point to a rival’s strength to spur domestic action has thus been a

double-edged sword. On the one hand, perceived threats can mobilize resources,

drive innovation, and foster unity in the face of potential challenges, as seen

with the space race and military advancements during the Cold War. A

useful overestimate galvanizes constructive action without leading to paranoia

or unsustainable commitments. Overestimates become damaging when they

dramatically skew government priorities and distract leaders’ finite attention

from other pressing issues. Recognizing the difference requires both a nuanced

understanding of a rival’s capabilities and the development of a

well-calibrated and sustainable response to them.

All That Glitters

Today, many in the

United States fear that China will eclipse its power. On the surface, evidence

for this prediction is abundant. In a variety of key capabilities, from

hypersonic missiles to shipbuilding, China is increasingly powerful, if not

dominant, which appears to demonstrate that China’s state-driven

political-economic model remains more than capable of “concentrating power to

do big things,” as Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping put it.

Yet the foundations

of China’s strength are strained by mounting challenges. The country’s growth

rate has steadily declined from its 2007 peak; the past five years, in particular, have ushered in stark structural problems

and economic volatility. The real estate market, a core driver of China’s

growth and urban development, is experiencing a historic correction with

far-reaching implications. In August 2024, the International Monetary Fund

estimated that roughly 50 percent of Chinese property developers are on the

brink of insolvency. Their woes are driven in part by a persistent decline in

housing prices, which as of October 2024, were falling

at their fastest pace since 2015. Because more than 70 percent of Chinese

household wealth is tied up in the property market, steep drops in the value of

housing hurt not only developers but nearly all Chinese citizens.

The real estate

crisis is affecting the finances of China’s local governments, too. These

municipalities were long reliant on land sales to fund

investment in public services and infrastructure. As property values and land

sales falter, these municipalities are becoming strapped for revenue,

preventing them from servicing their debt and providing essential services. In

an April 2024 analysis, Bloomberg estimated that China’s local governments had,

that month, generated their lowest revenue from land sales in eight years. To

compensate, they have resorted to collecting arbitrary fines from local

companies, clawing back bonuses paid to local officials, and even seeking loans

from private firms to cover payroll.

Even Chinese

citizens’ faith in Beijing’s economic stewardship is eroding. According

to The Wall Street Journal, as much as $254 billion may have

quietly flowed out of the country between June 2023 and June 2024—a clear

signal of domestic disillusionment. Young people are turning to a posture they

call “lying flat,” a quiet rebellion against societal expectations that demand

relentless effort in exchange for increasingly elusive rewards. With youth

unemployment surging to record levels, young Chinese people face a bleak

reality: advanced degrees and grueling work no longer guarantee stable

employment or upward mobility.

The external

environment that formerly supported China’s meteoric rise is also characterized

by wariness. Foreign companies that once rushed to tap the potential of China’s

vast market are now approaching it with caution, and some are even seeking the

exits. Foreign direct investment into China plunged 80 percent between 2021 and

2023, reaching its lowest level in 30 years. Beijing’s 2021 crackdown on the

tech sector wiped out billions of dollars in value, and the country’s

unpredictable regulatory and political environment has forced multinational

corporations to rethink their China strategies. In September, a survey by the

American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai revealed a grim outlook: fewer than

half of foreign firms expressed optimism about China’s five-year business

prospects—the lowest levels of confidence in the survey’s 25-year history.

In the years

following its accession into the World Trade Organization, China was warmly

welcomed into global markets, with countries eager to benefit from its

manufacturing prowess and seemingly limitless appetite for foreign investment.

China remains deeply reliant on access to the world’s markets, but many foreign

governments are growing ever more concerned about the strategic implications of

China’s economic reach and military might. Many developing countries that

initially embraced its Belt and Road Initiative as a

pathway to infrastructure development, for example, are scrutinizing the

project’s impact, worried about its negative effects on the environment and on

local labor practices. Advanced economies such as Australia and Canada have

erected new investment screening mechanisms to better protect their economies

from national security risks stemming from Chinese investment. In March 2019,

in a “strategic outlook” report, the European Commission formally labeled China

a “systemic rival,” marking a shift from the traditional view that the country

offered a market opportunity with few downsides. The EU subsequently moved to

impose stricter regulations on Chinese investments in Europe’s critical

infrastructure, technology, and digital sectors and tariffs of up to 45 percent

on Chinese-made electric vehicles.

Xi, meanwhile, has

ushered in a governance style characterized by reactive, opaque

decision-making, which often exacerbates China’s domestic and international

tensions. By consolidating his authority within a small circle of loyalists, Xi

has weakened the internal checks and balances that might otherwise temper

policy decisions. Beijing’s handling of the initial COVID-19 outbreak is a

striking example: the suppression of critical information, along with the

silencing of whistleblowers, caused delays in the global response to the virus,

contributing to its rapid spread beyond China’s borders. What might have been a

well-coordinated local response metastasized into a global health crisis,

exposing China to international condemnation and illustrating the pitfalls of a

system that punishes dissent and cuts off sources of feedback.

Xi’s attempts to

reduce economic inequality and curb the excesses of China’s booming private

sector have followed a similarly opaque and erratic course. Policy missteps by

the central government—such as its reluctance to bail out local governments and

rein in shadow banking and capital markets—have intensified the fiscal pressure

on the Chinese economy, triggering liquidity crises for giant real estate

developers. Sudden and aggressive regulatory crackdowns in sectors such as

technology and private education have sent shock waves through China’s business

community and unsettled international investors. With his push to

institutionalize what he calls a “holistic national security concept”—in which

Beijing’s economic and political decision-making is guided by concerns about

regime security—Xi has begun to erode the very sources of dynamism that

propelled China’s rapid ascent. Since Deng began to open China’s economy in the

late 1970s, Chinese leaders have striven to offer the country pragmatic,

pro-market policies and to afford local politicians the flexibility to address

their areas’ specific challenges. But hamstrung, now, by rigid and top-down

directives that prioritize ideological conformity over practical solutions,

local politicians are ill equipped to tackle the mounting pressures of fiscal

insolvency and unemployment.

Entrepreneurs, once

key engines of China’s economic miracle, now operate in a climate of fear and

uncertainty, unsure of what Beijing’s next policy shift might be. The lack of

transparency or legal recourse in government decision-making reveals the deeper

flaws of centralized governance: policies are developed and carried out with

little consultation or explanation, leaving citizens and businesses to navigate

the fallout. Xi’s consolidation of power may offer short-term control and a

capacity to achieve certain strategic and technological outcomes through brute

force. But it risks rendering China’s policymaking apparatus increasingly

tone-deaf, out of touch with both domestic realities and global expectations.

Bones

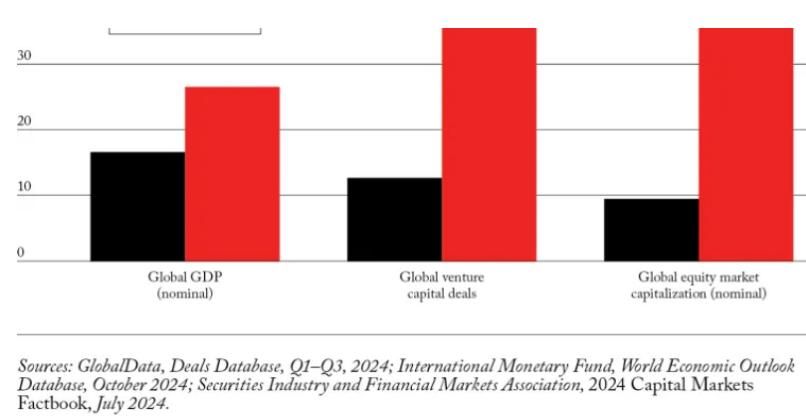

The extreme attitudes

of either fatalism or triumphalism can easily obscure a more nuanced

perspective that recognizes China’s expanding global influence while

appreciating the United States’ unique and enduring strategic advantages: its

resilient economy, innovative capacity, robust alliances, and open society. In

dollar-adjusted terms, the U.S. economy remains not only larger than China’s

but also larger than the next three biggest economies combined, and it is on

track to grow faster than any other G-7 economy in 2024 and 2025, according to

International Monetary Fund estimates. During President Joe Biden’s tenure, the

United States more than doubled its GDP lead over China, and its share of

global GDP remains near the level it was in the 1990s. Analysts such as the

Rhodium Group’s Logan Wright have predicted that China’s share of global GDP

peaked in 2021 and will likely remain below that of the United States for the

foreseeable future. Even observers who think the outlook for China’s economy is

less dire agree that its growth is slowing and will be constrained by

structural challenges and a clumsy policymaking process.

American companies

dominate global markets: as of March 2024, nine of the world’s ten largest

firms by market capitalization were American; China’s largest firm, Tencent,

ranked twenty-sixth. And the United States continues to attract the most

foreign capital of any economy, in stark contrast to China’s increasing capital

outflows. The United States also has more high-skilled immigrants than any

other country; China, meanwhile, struggles to attract any significant amount of

foreign-born talent.

As the artificial

intelligence revolution accelerates, the United States is particularly well

positioned to become the global epicenter of AI innovation and diffusion.

According to Stanford University’s Global AI Power Rankings, the United States

leads the world in artificial intelligence, possessing a substantial lead over

China in areas such as AI research, private-sector funding, and the development

of cutting-edge AI technologies. Over the past decade, the United States’ tech

sector has consistently outpaced China’s in AI, creating more than three times

as many AI-focused companies. In 2023, U.S. companies developed 61 significant

AI models compared with China’s 15, reflecting the strength of the United

States’ AI ecosystem. That same year, U.S. investors poured nearly nine times

more capital into AI than China did, funding the launch of 897 AI startups, far

surpassing China’s 122. This success stems in no small part from a

decentralized, market-driven approach that China, as it is currently governed,

cannot emulate. The United States’ relatively flexible regulatory framework,

the free collaboration it permits between private companies and academia, and

its ability to attract talent give it an edge.

As the world’s

largest oil importer, China relies on imports for over 70 percent of its oil

needs, leaving it vulnerable to global disruptions. Geopolitical tensions,

supply-chain bottlenecks, or regional conflicts could severely jeopardize

China’s energy security. The United States, by contrast, has nearly achieved

energy independence and has emerged as a leading global producer of oil and

natural gas. Its energy dominance is driven in part by strong innovation in

areas such as advanced fracking and horizontal drilling, and the United States

uses its preeminence to shape global energy markets and strengthen its

geopolitical leverage. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted Europe’s

energy supply, for example, the United States quickly increased its exports of

liquefied natural gas, reducing Europe’s dependence on Russian energy.

The dollar’s status

as the world’s primary reserve and settlement currency gives the United States

unparalleled financial leverage, although it also

has downsides. In 2023, nearly 60 percent of global foreign exchange reserves

were held in dollars, far outpacing the euro (around 20 percent) and the yuan

(less than three percent). That gives the United States advantages such as lower

borrowing costs, greater flexibility in managing its debt, and the ability to

impose sanctions. At the same time, the dollar’s global status imposes costs on

the U.S. economy, such as a persistent trade deficit and pressure on

manufacturing when it makes American exports less competitive. But these are

problems Beijing wishes it had: it is actively promoting alternatives to the

dollar and has unveiled a digital currency to try to blunt the United States’

ability to weaponize its financial system.

China’s investments

in aircraft carriers, stealth-capable submarines, and AI-driven systems are

reshaping the Indo-Pacific’s military balance and creating an undeniably

challenging operating environment for the U.S. force posture there. Beijing’s

defense industrial base now produces fifth-generation fighter jets, hypersonic

weapons, and sophisticated missile systems at scale. Its development of

anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities reflects a strategic focus on

limiting the U.S. military’s freedom of action in the western Pacific. Despite

these advancements, however, China’s military also faces serious obstacles. It

is grappling with corruption, which could undermine its operational efficiency

and readiness. Its lack of combat experience means that it is uncertain whether

it could execute complex operations under the pressures of modern warfare. And

any conflict within or near China’s territorial waters would likely have a

disproportionate impact on the Chinese economy, which relies heavily on maritime

trade and trade with its immediate region. The U.S. military’s ability to

project power on a global scale, by contrast, remains unmatched, supported by

extensive combat experience, a vast alliance network, and forward-deployed

forces stationed across the world.

Perhaps most

significantly, however, China cannot yet match the United States’ greatest

force multiplier: its global alliance system. The United States’ partnerships

with NATO and close treaty allies in the Pacific such as Australia,

Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea allow it to form a united front in the

face of natural disasters, technological competition, and adversarial

ambitions. These alliances are more than symbolic. They enable real-time

coordination that allows the United States to pre-position forces far from its

shores, thus amplifying its military effectiveness and readiness. A superpower

is a country capable of projecting force and exercising influence in every

corner of the world. The United States meets this definition. China does not,

at least not yet.

The decentralized

nature of the United States democratic system, in which significant governance

responsibilities remain vested with state and local authorities, remains an

American advantage, too. Unlike in China, the United States’ regular electoral

cycles and peaceful transfers of power enable citizens to insist on change when

they become dissatisfied with the country’s trajectory. Although the United

States must urgently address the many threats to its democratic norms from

extreme polarization and institutional erosion, it still boasts serious checks

on presidential power from a free media, an independent legislature, and a

transparent legal system.

False Ceiling

It is vital to

remember that Beijing’s greatest wins have tended to occur not despite American

efforts, but in their absence. Take 5G telecommunications: China developed and

deployed next-generation wireless networks at breakneck speed, cornering

markets in Africa, Asia, and parts of Europe. This did not happen because the

United States could not compete, but because it was slow to invest in domestic

alternatives and unwilling to mobilize resources to scale a national strategy

at China’s pace.

China’s especially

rapid advancements in quantum communications and satellite networks underscore

the extent to which it has prioritized leadership in technologies that the

United States has been slower to embrace or fund at scale. This success has

been driven by government subsidies, aggressive industrial policies, and a

singular focus on securing critical raw materials, often at a high geopolitical

and environmental price. These gains come with other costs, too. The Chinese

government’s laser focus on specific strategic domains has diverted its

attention and resources from projects that would drive longer-term economic

growth, such as reforming the social safety net and boosting domestic

consumption.

As China struggles,

the United States should press its advantage. To do so, U.S. policymakers

better make significant investments in areas in which the United States appears

strong, boosting funding for research and development and cutting-edge

industries, attracting global talent through targeted immigration reform,

fortifying alliances in Asia and Europe, and rebuilding the U.S. defense

industrial base. If American leaders continue to wring their hands over China’s

ascendancy instead of taking these crucial steps, Washington’s strategic

advantage could quickly erode.

It is undeniable that

the United States faces serious challenges. But it is equally undeniable that

it retains extraordinary strengths—and that its democratic institutions, albeit

stressed, possess a unique capacity for renewal. Competition between the United

States and Beijing will be a defining feature of the coming decades. But

although China’s centralized governance may deliver rapid advancements in key

areas, its gains are fragile. The real peril for the United States may lie not

in the unmatchable rise of a new rival but in its unwillingness to acknowledge

and build on its unmatched potential.

For updates click hompage here