By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Will America And China Heed The Warnings

In The Rise

of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860–1914, the British historian Paul

Kennedy explained how two traditionally friendly peoples ended up in a downward

spiral of mutual hostility that led to World War I. Major structural forces

drove the competition between Germany and Britain: economic imperatives,

geography, and ideology. Germany’s rapid economic rise shifted the balance of

power and enabled Berlin to expand its strategic reach. Some of this

expansion—especially at sea—took place in areas in which Britain had profound

and established strategic interests. The two powers increasingly viewed each

other as ideological opposites, wildly exaggerating their differences. The

Germans caricatured the British as moneygrubbing exploiters of the world, and

the British portrayed the Germans as authoritarian malefactors bent on

expansion and repression.

The two countries

appeared to be on a collision course, destined for war. But it wasn’t

structural pressures, important as they were, that sparked World War I. War

broke out thanks to the contingent decisions of individuals and a profound lack

of imagination on both sides. To be sure, war was always likely. But it was

unavoidable only if one subscribes to the deeply ahistorical view that

compromise between Germany and Britain was impossible.

The war might not

have come to pass had Germany’s leaders after Chancellor Otto von Bismarck not

been so brazen about altering the naval balance of power. Germany celebrated

its dominance in Europe and insisted on its rights as a great power, dismissing

concerns about rules and norms of international behavior. That posture alarmed

other countries, not just Britain. And it was difficult for Germany to claim,

as it did, that it wanted to make a new, more just and inclusive world order

while it threatened its neighbors and allied with a decaying Austro-Hungarian

Empire that was hard at work denying the national aspirations of the peoples on

its borders.

A similar tunnel

vision prevailed on the other side. Winston Churchill, the British naval chief,

concluded in 1913 that Britain’s preeminent global position “often seems less

reasonable to others than to us.” British views of others tended to lack that self-awareness.

Officials and commentators spewed vitriol about Germany, inveighing

particularly against unfair German trade practices. London eyed Berlin warily,

interpreting all its actions as evidence of aggressive intentions and failing

to understand Germany’s fears for its own security on a continent where it was

surrounded by potential foes. British hostility, of course, only deepened

German fears and stoked German ambitions. “Few seem to have possessed the

generosity or the perspicacity to seek a large-scale improvement in

Anglo-German relations,” Kennedy lamented.

Such generosity or

perspicacity is also sorely missing in relations between China and the United

States today. Like Germany and Britain before World War I, China and the United

States seem to be locked in a downward spiral, one that may end in disaster for

both countries and for the world at large. Similar to the situation a century

ago, profound structural factors fuel the antagonism. Economic competition,

geopolitical fears, and deep mistrust work to make conflict more likely.

But structure is not

destiny. The decisions that leaders make can prevent war and better manage the

tensions that invariably rise from great-power competition. As with Germany and

Britain, structural forces may push events to a head, but it takes human avarice

and ineptitude on a colossal scale for disaster to ensue. Likewise, sound

judgment and competence can prevent the worst-case scenarios.

The Lines Are Drawn

Much like the

hostility between Germany and Britain over a century ago, the antagonism

between China and the United States has deep structural roots. It can be traced

to the end of the Cold War. In the latter stages of that great conflict,

Beijing and Washington had been allies of sorts, since both feared the power of

the Soviet Union more than they feared each other. But the collapse of the

Soviet state, their common enemy, almost immediately meant that policymakers

fixated more on what separated Beijing and Washington than what united them.

The United States increasingly deplored China’s repressive government. China

resented the United States’ meddlesome global hegemony.

But this sharpening

of views did not lead to an immediate decline in U.S.-Chinese relations. In the

decade and a half that followed the end of the Cold War, successive U.S.

administrations believed they had a lot to gain from facilitating China’s

modernization and economic growth. Much like the British, who had initially

embraced the unification of Germany in 1870 and German economic expansion after

that, the Americans were motivated by self-interest to abet Beijing’s rise.

China was an enormous market for U.S. goods and capital, and, moreover, it

seemed intent on doing business the American way, importing American consumer

habits and ideas about how markets should function as readily as it embraced

American styles and brands.

At the level of

geopolitics, however, China was considerably more wary of the United States.

The collapse of the Soviet Union shocked China’s leaders, and the U.S. military

success in the 1991 Gulf War brought home to them that China now existed in a

unipolar world in which the United States could deploy its power almost at

will. In Washington, many were repelled by China’s use of force against its own

population at Tiananmen Square in 1989 and elsewhere. Much like Germany and

Britain in the 1880s and 1890s, China and the United States began to view each

other with greater hostility even as their economic exchanges expanded.

What really changed

the dynamic between the two countries was China’s unrivaled economic success.

As late as 1995, China’s GDP was around ten percent of U.S. GDP. By 2021, it

had grown to around 75 percent of U.S. GDP. In 1995, the United States produced

around 25 percent of the world’s manufacturing output, and China produced less

than five percent. But now China has surged past the United States. Last year,

China produced close to 30 percent of the world’s manufacturing output, and the

United States produced just 17 percent. These are not the only figures that

reflect a country’s economic importance, but they give a sense of a country’s

heft in the world and indicate where the capacity to make things, including

military hardware, resides.

At the geopolitical

level, China’s view of the United States began to darken in 2003 with the

invasion and occupation of Iraq. China opposed the U.S.-led attack, even if

Beijing cared little for Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s regime. More than the

United States’ devastating military capabilities, what really shocked leaders

in Beijing was the ease with which Washington could dismiss matters of

sovereignty and nonintervention, notions that were staples of the very

international order the Americans had coaxed China to join. Chinese

policymakers worried that if the United States could so readily flout the same

norms it expected others to uphold, little would constrain its future behavior.

China’s military budget doubled from 2000 to 2005 and then doubled again by

2009. Beijing also launched programs to better train its military, improve its

efficiency, and invest in new technology. It revolutionized its naval and

missile forces. Sometime between 2015 and 2020, the number of ships in the

Chinese navy surpassed that in the U.S. Navy.

Some argue that China

would have dramatically expanded its military capabilities no matter what the

United States did two decades ago. After all, that is what major rising powers

do as their economic clout increases. That may be true, but the specific timing

of Beijing’s expansion was clearly linked to its fear that the global hegemon

had both the will and the capacity to contain China’s rise if it so chose.

Iraq’s yesterday could be China’s tomorrow, as one Chinese military planner put

it, somewhat melodramatically, in the aftermath of the U.S. invasion. Just as

Germany began fearing that it would be hemmed in both economically and

strategically in the 1890s and the early 1900s—exactly when Germany’s economy

was growing at its fastest clip—China began fearing it would be contained by

the United States just as its own economy was soaring.

Before The Fall

If there was ever an

example of hubris and fear coexisting within the same leadership, it was

provided by Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm II. Germany believed both that it was

ineluctably on the rise and that Britain represented an existential threat to

its ascent. German newspapers were full of postulations about their country’s

economic, technological, and military advances, prophesying a future when

Germany would overtake everyone else. According to many Germans (and some

non-Germans, too), their model of government, with its efficient mix of

democracy and authoritarianism, was the envy of the world. Britain was not

really a European power, they claimed, insisting that Germany was now the

strongest power on the continent and that it should be left free to rationally

reorder the region according to the reality of its might. And indeed, it would

be able to do just that if not for British meddling and the possibility that

Britain could team up with France and Russia to contain Germany’s success.

Nationalist passions

surged in both countries from the 1890s onward, as did darker notions of the

malevolence of the other. The fear grew in Berlin that its neighbors and

Britain were set on derailing Germany’s natural development on its own

continent and preventing its future predominance. Mostly oblivious to how their

own aggressive rhetoric affected others, German leaders began viewing British

interference as the root cause of their country’s problems, both at home and

abroad. They saw British rearmament and more restrictive trade policies as

signs of aggressive intent. “So the celebrated encirclement of Germany has

finally become an accomplished fact,” Wilhelm sighed, as war was brewing in

1914. “The net has suddenly been closed over our head, and the purely

anti-German policy which England has been scornfully pursuing all over the

world has won the most spectacular victory.” On their side, British leaders

imagined that Germany was largely responsible for the relative decline of the

British Empire, even though many other powers were rising at Britain’s expense.

China today shows

many of the same signs of hubris and fear that Germany exhibited after the

1890s. Leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took immense pride in

navigating their country through the 2008 global financial crisis and its

aftermath more adeptly than did their Western counterparts. Many Chinese

officials saw the global recession of that era not only as a calamity made in

the United States but also as a symbol of the transition of the world economy

from American to Chinese leadership. Chinese leaders, including those in the

business sector, spent a great deal of time explaining to others that China’s

inexorable rise had become the defining trend in international affairs. In its

regional policies, China started behaving more assertively toward its

neighbors. It also crushed movements for self-determination in Tibet and

Xinjiang and undermined Hong Kong’s autonomy. And in recent years, it has more

frequently insisted on its right to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary,

and has begun to intensify its preparations for such a conquest.

Together, growing

Chinese hubris and rising nationalism in the United States helped hand the

presidency to Donald Trump in 2016, after he appealed to voters by conjuring

China as a malign force on the international stage. In office, Trump began a

military buildup directed against China and launched a trade war to reinforce

U.S. commercial supremacy, marking a clear break from the less hostile policies

pursued by his predecessor, Barack Obama. When Joe Biden replaced Trump in

2021, he maintained many of Trump’s policies that targeted China—buoyed by a

bipartisan consensus that sees China as a major threat to U.S. interests—and

has since imposed further trade restrictions intended to make it more difficult

for Chinese firms to acquire sophisticated technology.

A World War I–era trench in Massiges,

France, November 2018

Beijing has responded

to this hard-line shift in Washington by showing as

much ambition as insecurity in its dealings with others. Some of its complaints

about American behavior are strikingly similar to those that Germany lodged

against Britain in the early twentieth century. Beijing has accused Washington

of trying to maintain a world order that is inherently unjust—the same

accusation Berlin leveled at London. “What the United States has constantly

vowed to preserve is a so-called international order designed to serve the

United States’ own interests and perpetuate its hegemony,” a white paper

published by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared in June 2022. “The

United States itself is the largest source of disruption to the actual world

order.”

The United States,

meanwhile, has been trying to develop a China policy that combines deterrence

with limited cooperation, similar to what Britain did when developing policy

toward Germany in the early twentieth century. According to the Biden

administration’s October 2022 National Security Strategy, “The People’s

Republic of China harbors the intention and, increasingly, the capacity to

reshape the international order in favor of one that tilts the global playing

field to its benefit.” Although opposed to such a reshaping, the administration

stressed that it will “always be willing to work with the PRC where our

interests align.” To reinforce the point, the administration declared, “We

can’t let the disagreements that divide us stop us from moving forward on the

priorities that demand that we work together.” The problem now is—as it was in

the years before 1914—that any opening for cooperation, even on key issues,

gets lost in mutual recriminations, petty irritations, and deepening strategic

mistrust.

In the British-German

relationship, three main conditions led from rising antagonism to war. The

first was that the Germans became increasingly convinced that Britain would not

allow Germany to rise under any circumstances. At the same time, German leaders

seemed incapable of defining to the British or anyone else how, in concrete

terms, their country’s rise would or would not remake the world. The second was

that both sides feared a weakening of their future positions. This view,

ironically, encouraged some leaders to believe that they should fight a war

sooner rather than later. The third was an almost total lack of strategic

communication. In 1905, Alfred von Schlieffen, chief of the German general

staff, proposed a battle plan that would secure a swift victory on the

continent, where Germany had to reckon with both France and Russia. Crucially,

the plan involved the invasion of Belgium, an act that gave Britain an

immediate cause to join the war against Germany. As Kennedy put it, “The

antagonism between the two countries had emerged well before the Schlieffen

Plan was made the only German military strategy; but it took the sublime genius

of the Prussian General Staff to provide the occasion for turning that

antagonism into war.”

All these conditions

now seem to be in place in the U.S.-Chinese relationship. Chinese President Xi

Jinping and the CCP leadership are convinced the United States’ main objective

is to prevent China’s rise no matter what. China’s own statements regarding its

international ambitions are so bland as to be next to meaningless. Internally,

Chinese leaders are seriously concerned about the country’s slowing economy and

about the loyalty of their own people. Meanwhile, the United States is so

politically divided that effective long-term governance is becoming almost

impossible. The potential for strategic miscommunication between China and the

United States is rife because of the limited interaction between the two sides.

All current evidence points toward China making military plans to one day

invade Taiwan, producing a war between China and the United States just as the

Schlieffen Plan helped produce a war between Germany and Britain.

A New Script

The striking

similarities with the early twentieth century, a period that witnessed the

ultimate disaster, point to a gloomy future of escalating confrontation. But

conflict can be avoided. If the United States wants to prevent a war, it has to

convince Chinese leaders that it is not hell-bent on preventing China’s future

economic development. China is an enormous country. It has industries that are

on par with those in the United States. But like Germany in 1900, it also has

regions that are poor and undeveloped. The United States cannot, through its

words or actions, repeat to the Chinese what the Germans understood the British

to be telling them a century ago: if you only stopped growing, there would not

be a problem.

At the same time,

China’s industries cannot keep growing unrestricted at the expense of everyone

else. The smartest move China could make on trade is to agree to regulate its

exports in such a way that they do not make it impossible for other countries’ domestic

industries to compete in important areas such as electric vehicles or solar

panels and other equipment necessary for decarbonization. If China continues to

flood other markets with its cheap versions of these products, a lot of

countries, including some that have not been overly concerned by China’s

growth, will begin to unilaterally restrict market access to Chinese goods.

Unrestricted trade

wars are not in anyone’s interest. Countries are increasingly imposing higher

tariffs on imports and limiting trade and the movement of capital. But if this

trend turns into a deluge of tariffs, then the world is in trouble, in economic

as well as political terms. Ironically, China and the United States would

probably both be net losers if protectionist policies took hold everywhere. As

a German trade association warned in 1903, the domestic gains of protectionist

policies “would be of no account in comparison with the incalculable harm which

such a tariff war would cause to the economical

interests of both countries.” The trade wars also contributed significantly to

the outbreak of a real war in 1914.

Containing trade wars

is a start, but Beijing and Washington should also work to end or at least

contain hot wars that could trigger a much wider conflagration. During intense

great-power competition, even small conflicts could easily have disastrous consequences,

as the lead-up to World War I showed. Take, for instance, Russia’s current war

of aggression against Ukraine. Last year’s offensives and counteroffensives did

not change the frontlines a great deal; Western countries hope to work toward a

cease-fire in Ukraine under the best conditions that Ukrainian valor and

Western weapons can achieve. For now, a Ukrainian victory would consist of the

repulsion of the initial all-out 2022 Russian offensive as well as terms that

end the killing of Ukrainians, fast-track the country’s accession into the EU,

and obtain Kyiv security guarantees from the West in case of Russian cease-fire

violations. Many in the Western camp hope that China could play a constructive

role in such negotiations, since Beijing has stressed “respecting the

sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries.” China should remember

that one of Germany’s major mistakes before World War I was to stand by as

Austria-Hungary harassed its neighbors in the Balkans even as German leaders

appealed to the high principles of international justice. This hypocrisy helped

produce war in 1914. Right now, China is repeating that mistake with its

treatment of Russia.

Although the war in

Ukraine is now causing the most tension, it is Taiwan that could be the Balkans

of the 2020s. Both China and the United States seem to be sleepwalking toward a

cross-strait confrontation at some point within the next decade. An increasing

number of China’s foreign policy experts now think that war over Taiwan is more

likely than not, and U.S. policymakers are preoccupied with the question of how

best to support the island. What is remarkable about the Taiwan situation is

that it is clear to all involved—except, perhaps, to the Taiwanese most fixed

on achieving formal independence—that only one possible compromise can likely

help avoid disaster. In the Shanghai Communique of 1972, the United States

acknowledged that there is only one China and that Taiwan is part of China.

Beijing has repeatedly stated that it seeks an eventual peaceful unification

with Taiwan. A restatement of these principles today would help prevent a

conflict: Washington could say that it will under no circumstances support

Taiwan’s independence, and Beijing could declare that it will not use force

unless Taiwan formally takes steps toward becoming independent. Such a

compromise would not make all the problems related to Taiwan go away. But it

would make a great-power war over Taiwan much less likely.

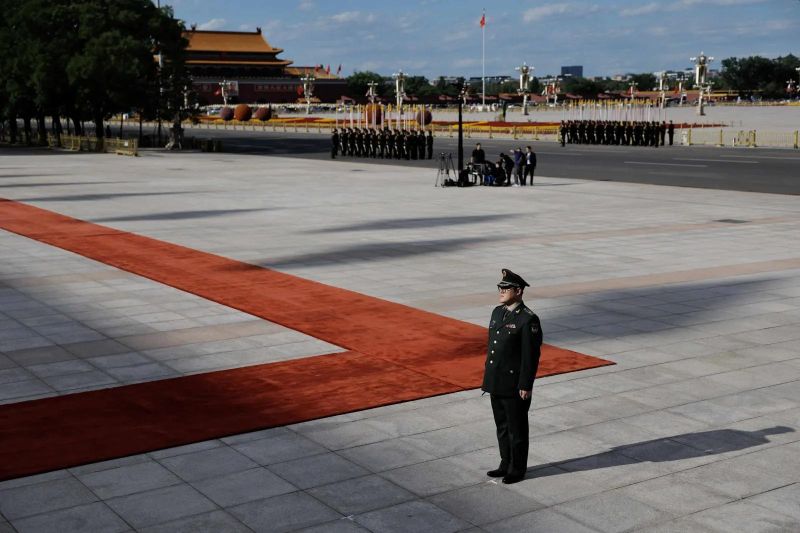

A Chinese soldier in Beijing, May 2024

Reining in economic

confrontation and dampening potential regional flash points are essential for

avoiding a repeat of the British-German scenario, but the rise of hostility

between China and the United States has also made many other issues urgent.

There is a desperate need for arms control initiatives and for dealing with

other conflicts, such as that between the Israelis and the Palestinians. There

is a demand for signs of mutual respect. When, in 1972, Soviet and U.S. leaders

agreed to a set of “Basic Principles of Relations Between the United States of

America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,” the joint declaration

achieved almost nothing concrete. But it built a modicum of trust between both

sides and helped convince Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev that the Americans were

not out to get him. If Xi, like Brezhnev, intends to remain leader for life,

that is an investment worth making.

The rise of

great-power tensions also creates the need to maintain believable deterrence.

There is a persistent myth that alliance systems led to war in 1914 and that a

web of mutual defense treaties ensnared governments in a conflict that became

impossible to contain. In fact, what made war almost a certainty after the

European powers started mobilizing against one another in July 1914 was

Germany’s ill-considered hope that Britain might not, after all, come to the

assistance of its friends and allies. For the United States, it is essential

not to provide any cause for such mistakes in the decade ahead. It should

concentrate its military power in the Indo-Pacific, making that force an

effective deterrent against Chinese aggression. And it should reinvigorate

NATO, with Europe carrying a much greater share of the burden of its own

defense.

Leaders can learn

from the past in both positive and negative ways, about what to do and what not

to do. But they have to learn the big lessons first, and the most important of

all is how to avoid horrendous wars that reduce generations of achievements to

rubble.

For updates click hompage here