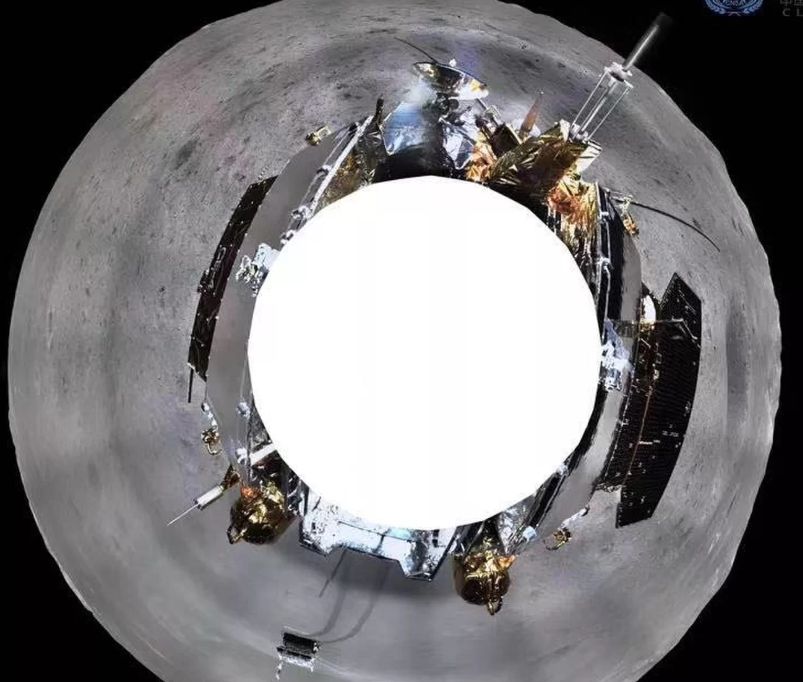

On 3 Jan. 2019 the

whole world watched how

a Chinese spacecraft landed on the far side of the moon.

“This is a great

technological accomplishment as it was out of sight of Earth, so signals are

relayed back by their orbiter, and most of the landing was actually done

autonomously in difficult terrain,” said Prof Andrew Coates, a space scientist

at UCL’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory. “The landing was almost vertical

because of the surrounding hills.”

Chang’e-4’s landing

site in Von Kármán crater, though, is on the far side of the Moon, where the

spacecraft can no more easily be reached by radio than it can be seen through a

telescope. Landing there and getting data back afterward is possible only with

the help of a cunningly pre-positioned relay satellite. Other countries have

considered such missions, but none has ever mounted one. China has been

carefully building up the capacity to go where they have not; now it has done

so.

China is keen on such

signals of pre-eminence and willing to put in the work they require. It wants the world, and its own people, to know that it

is a global power--that it boasts not just a titanic economy, but the

geopolitical sway and military might to match, soft power of all sorts, a

storied past and a glorious future. Science is a big part of this. It is seen

in China, as elsewhere, as an ennobling pursuit and a necessary foundation for

technological advance. China’s leaders see such advances as crucial not just to

their economy, but also to expanded military prowess and social progress. They

want the sort of science that will help China project its power and respond to

its people’s particular problems. They want new clean-energy sources and

freedom from resource constraints. And the country’s ever greater scientific

proficiency makes such ambitions look realizable. It is a long way from landing

on the Moon to mining it. But it is not uncommon to hear speculation about such

things.

Earlier in August

2018 Trym Eiterjord writing for the Diplomat,

remarked about the looming challenge for science in China: that

the restoration of Mr. Science would likely necessitate a greater space for his

companion, Mr. Democracy. After the fall of the Qing dynasty, in the first

decades of the new republic, Chinese intellectuals were mapping the possible

pathways of a Chinese modernity. This period, culminating

in the May Fourth Movement in 1919, saw a myriad of different political

programs spar against each other. One overarching concern was the relationship

between democracy and science--or rather, a discussion of whether a wholesale

importation of European Enlightenment values was necessary for ensuring China’s

own modernity. Taken as two fundamental elements of modernity, science and

democracy became personified as Mr. Science and Mr. Democracy in the writings

of Chen Duxiu, one of the founders of the Chinese Communist Party. Mr.

Democracy and Mr. Science, it was thought, would replace old Confucian modes of

organization, jettison traditional epistemologies, and promptly help usher in a

truly modern China. For Chen, China’s political, intellectual, and moral

ailments could all be cured by a comprehensive adoption of scientific and

democratic values. In the magazine New Youth, Chen asked the reader to consider

the “many upheavals” that had occurred in the West “in support of Mr. Democracy

and Mr. Science, before these two gentlemen gradually led Westerners out of

darkness” and argued that only these two forces could “resuscitate China.”

Xi’s determination

There is no doubting

President Xi Jinping ‘s determination. Modern science depends on money,

institutions and oodles of brainpower. Partly because its government can

marshal all three, China is hurtling up the rankings of scientific achievement.

As the investigation

below shows, China has spent many billions of dollars on machines to detect

dark matter and neutrinos and on institutes galore that delve into everything

from genomics and quantum communications to renewable energy and advanced materials.

An analysis of 17.2m papers in 2013-18, by Nikkei, a Japanese publisher, and

Elsevier, a scientific publisher, found that more came from China than from any

other country in 23 of the 30 busiest fields, such as sodium-ion batteries and

neuron-activation analysis. The quality of American research has remained

higher, but China has been catching up, accounting for 11% of the most

influential papers in 2014-16.

Such is the pressure

on Chinese scientists to make breakthroughs that some put ends before means.

Last year He Jiankui, an academic from Shenzhen, edited the genomes of embryos

without proper regard for their post-partum welfare—or that of any children they

might go on to have. Chinese artificial-intelligence (AI) researchers are

thought to train their algorithms on data harvested from Chinese citizens with

little oversight. In 2007 China tested a space-weapon on one of its weather

satellites, littering orbits with lethal space debris. Intellectual-property

theft is rampant.

But Chinese science

is about much more than weapons and oppression. From better batteries and new

treatments for disease to fundamental discoveries about, say, dark matter, the

world has much to gain from China’s efforts.

Moreover, it is

unclear whether Xi is right. If Chinese research really is to lead the field,

then science may end up changing China in ways he is not expecting.

Money counts also

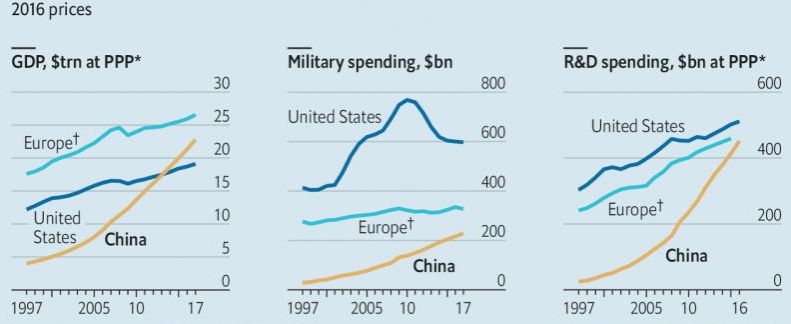

The huge hopes China

has for science have prompted huge expenditure. Chinese spending on R&D

grew tenfold between 2000 and 2016. This open checkbook has bought a lot of

glitzy kit. Somewhere in the Haidian district of

Beijing, which houses the Ministry of Science and Technology as well as

Tsinghua and Peking Universities, it seems there is a civil servant quietly

ticking things off a list of scientific status symbols. Human space flight?

Tick. Vast genome-sequencing facilities? Tick. Fleet of research vessels? Tick.

World’s largest radio telescope? Tick. Climate researchers drilling cores deep

into the Antarctic ice cap? Tick. World’s most powerful supercomputer? Tick

(erased when America regained its lead, but watch this space). Underground

neutrino and dark-matter detectors? Tick and tick. World’s largest particle

accelerator? The pencil is

hovering.

The spree is

tellingly reminiscent of the golden years of “big science” in post-war America.

Between the International Geophysical Year of 1957 and the cancellation of the

Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) in 1993, America’s government unfailingly

invested ever more of the resources of an ever more powerful economy into the

things which the leaders of its scientific community most wanted. From the

creation of quarks to the cloning of genes to the netting of Nobel prizes,

American science came to dominate the world.

Over those 40 years

America—and, to a lesser extent, Europe—were doing things that had never been

done before. They opened up whole new fields of knowledge such as high-energy

astrophysics and molecular biology. Benefiting from the biggest and best-educated

native generations ever produced, they also welcomed in the brightest from

around the world. And they did so in a culture dedicated to free inquiry, one

keenly differentiated from the communist culture of the Soviet bloc.

Measured against that

boom—one of the most impressive periods of scientific achievement in human

history—China’s new hardware, grand as it often is, falls a bit short. It has

been catching up, not forging ahead. It has not been a beacon for scientists elsewhere.

And far from benefiting from a culture of free inquiry, Chinese science takes

place under the beady eye of a Communist Party and government which wants the

fruits of science but are not always comfortable about the untrammelled

flow of information and the spirit of doubt and critical scepticism

from which they normally grow.

America’s science

boom had a firm institutional and ideological foundation. It grew out of the

great research universities that came into their own in the first half of the

20th century, and whose intellectual freedom had attracted

extraordinary talents threatened by regimes elsewhere, including Albert

Einstein, Enrico Fermi and indeed Theodore von Kármán, the Hungarian-born

aeronautical engineer in whose honour Chang’e-4’s new

home is named. China has imported ideas and approaches more than people and

ideals. The resultant set-up has the ricketiness often seen in structures

ordained from the top down rather than built from the bottom up.

Top-down ambition can

mean running before you walk. Take FAST, the Five-hundred-metre

Aperture Spherical Telescope, which opened in 2016. Built in a natural basin in

Guizhou province, it is more than twice

the size of the world’s next-largest radio telescope, in America. But FAST

does not have a director. Having leaped from nowhere to the top of the tree in

terms of hardware, the country finds itself in the embarrassing position of

having no radio-astronomer to hand who combines the scientific and administrative

skills needed to run the thing.

Self-defeating

shortcuts, symbolic and otherwise, are not only the preserve of the government;

Chinese scientists are prey to such temptations, too. China is not only

recapitulating American science’s cold-war national-prestige boom. It is doing

so in the context of the subsequent high-technology era in which no American

university feels complete without a symbiotic microbiome of venture capitalists

pullulating across its skin. The economic benefits of research have

increasingly come to be seen as a possible boon to the researcher, as well as

to society at large.

For a particularly

egregious example, consider the most notable Chinese scientific first of 2018.

He Jiankui looked like the model of a modern Chinese scientist. He was educated

at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) in Hefei. He went

on to equally prestigious American universities, Rice and Stanford. He was

brought back by the government’s “Thousand Talents” programme

to a new position at the Southern University of Science and Technology in

Shenzhen. Once established there, he took unpaid leave to start an

entrepreneurial project.

That project was

editing the DNA of embryos that would then grow up into human beings. Its

result was two baby girls. They do not, as yet, appear unhealthy. Nor, though,

have they been provided with the questionable advantages Dr He Jiankui says he was trying to provide through his

tinkering—tinkering which was unsanctioned, illegal and which, since he went

public, has seen opprobrium heaped upon him.Since

then Shenzhen authorities have tightened

the ethical review process for biomedical research involving humans with its

own set of local regulations.

You can’t clone success

The He affair could have

taken place in many places, and it is hardly representative of the broad swathe

of China’s researchers; 122 of them signed an open letter denouncing his

actions. At the same time, it is not at all surprising that the He affair took

place in China. It was a perversion of what Chinese scientists are trying to

achieve as they seek to establish themselves and their country in the world of

elite science. But it was also an illustration of it.

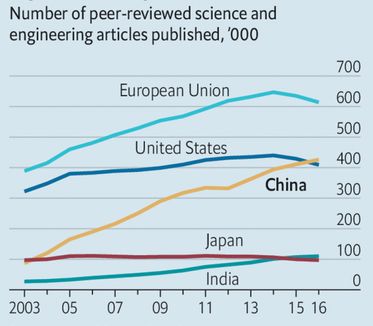

The staggering growth

in the number of scientific papers by Chinese researchers needs to be seen in

this context. In terms of pure numbers, China overtook America in 2016 (see

chart 2). But the quality of some of these papers is very low. In April 2018 Han

Xueying and Richard Appelbaum of the University of

California, Santa Barbara, reported opinions gathered in a survey of 731

researchers at top-tier Chinese universities. As one from Fudan University put

it: “People fabricate or plagiarise papers so that they

can pass their annual performance evaluations.”

The Chinese

government is aware of the risks of a reputation for poor and even fraudulent

research. It is one of the reasons that it is orchestrating the development of

a scientific establishment. One of its pillars is a core group of elite

universities known as the C9. Fudan is one of them, as are Tsinghua and Peking

Universities and Dr He’s alma mater, USTC. The other is the Chinese Academy of

Sciences (CAS), an official agency that runs laboratories of its own, which

will adhere to prevailing international standards. The government is clamping

down on shoddy journals, especially those in which researchers pay to be

published. Raising standards in this way will not just improve science; it will

also attract the best scientists.

After Deng Xiaoping

came to power in 1978 the top tier of Chinese students was encouraged to go

abroad for their graduate studies. Many returned, as had been intended, filled

with knowledge unavailable at home. Without them the current scientific boom would

not have happened, however much the government had spent. But the best often

chose to stay abroad. In 2008 the country started the Thousand Talents programme to draw these exiles back with promises of lucre

and lab space.

In theory, the programme is open to any top-notch researcher working in an

overseas laboratory, regardless of nationality. In practice, few non-Chinese have availed themselves of it. But many Chinese

have. Such returners are known as haigui, the Chinese

for “sea turtle”, since they are thought of as having come back to their natal

beach, as turtles do, to lay their eggs.

Talent that has not

been abroad is not, however, neglected. A coeval programme,

Changjiang Scholars, is aimed at identifying potential top-flight researchers

who are languishing in thousands of provincial institutions. Once identified,

they, too, are brought into the charmed circle.

Ventures into relativly new

fields

This is yielding

results at all but the very highest levels. Chinese scientists working in China

have as yet earned only one Nobel prize. Other than that work, the discovery of

artemisinin, a novel antimalarial drug, by Tu Youyou,

there has not yet been any Chinese scientific advance that a fair-minded person

would be likely to think Nobel-worthy. No fundamental particle has been

discovered there, nor any new class of astronomical object. Chinese scientists

have not yet done anything to compare with, say, the development of CRISPR-Cas9

gene editing (America) or the creation of pluripotent stem cells (Japan) or the

invention of DNA sequencing itself (Britain).

But a great deal of

Chinese science is now very good indeed, particularly in relatively new fields

with practical implications. The country has a very large and ever growing

workforce (see chart 3) that is both enjoined and keen to tackle juicy topics.

A study published by Elsevier, a scientific publisher, and Nikkei, a Japanese

news business, on January 6th found that China published more

high-impact research papers than America did in 23 out of 30 hot research fields

with clear technological applications. Chinese science is a nimble giant,

capable of piling in on any new field of promise with enormous, often centrally

encouraged, force.

Developments in fields

such as double-layer capacitors and biochar, two of those 23, may be important

but are unlikely to be much noticed, either by Nobel committees, the public or

foreigners who need impressing. For visible signals of its national prowess,

China is following the well-trodden path of big science in America, Europe, and

Japan: building large physics experiments and putting things—especially

people—into space.

The China National

Space Administration has sent several “taikonauts” into orbit and provided them

with some small space labs to hang around in while they are there. Its plans

include, in the near term, a bigger space station, assembled in orbit from modules

launched separately, and in the longer, term crewed missions to the Moon

enabled by a new booster more powerful than any of today’s, the Long March 9.

The National Space

Science Centre, part of CAS, is busy putting up scientific satellites; in April

2018 it announced six new ones that should be launched by 2020 or soon after.

Most of China’s launches, though, are not scientific; they are for communications,

Earth observation—and military intelligence. China’s space programme

began in the bosom of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and though it is no

longer directly run by the armed forces, they are still keenly involved with

the development of the country’s orbital abilities. In 2007 China tested an

anti-satellite weapon; its “Strategic Support Force” is thought to coordinate

its military space-, electronic- and cyber-warfare capabilities. All China’s

taikonauts are PLA officers. Other physics facilities have obvious military

applications, too, such as wind tunnels designed for research into forms of

hypersonic flight that are really relevant only to the armed forces.

Beyond rocketry,

China’s most ambitious big-science plan is to build the largest particle

accelerator ever. Since their development in the 1930s, circular particle

accelerators have grown from the size of a room to the size of the Large Hadron

Collider (LHC), which occupies a 27km loop of tunnel beneath the Franco-Swiss

border at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics laboratory. The bigger the

accelerator, the more energy it can pump into its particles. The LHc packs its protons with more than a million times more

energy than the original machines did in 1930s Berkeley.

Sharpening the gene shears

The Chinese plan

foresees a loop of tunnel as much as 100km long. Even China will not be able to

foot the bill for such a beast alone. In the 2000s the LHC cost CERN over

SFr4bn ($5bn); contributions to its experiments from other countries, including

China and America, significantly increased the total. Making use of it has cost

billions more. Nor would China be able to supply all the physicists needed to

make use of such a facility. Like the LHC, the next accelerator will be a

single lab for the world, wherever it is: these toys are one-per-planet

affairs. But the Chinese seem more serious than anyone else about hosting and

building the thing. Just as it meant something beyond the world of particle

physics when America canceled its proposed giant SSC and CERN’s LHC became the

biggest game in town, so it would mean something if China took CERN’s crown.

Particle physics

enjoys a particular prestige in part because of its early (and now dissolved)

association with the development of nuclear weapons, in part because of the

conceptual depths it plumbs, in part because of the sheer size and expense of

its tools. But there are other parts of physics with more of the cutting edge

about them. These include applications of the more abstruse aspects of quantum

mechanics to computation and cryptography, an area where China is a world

leader: it was the first country to send a quantum-encrypted message via a

satellite. In computer science, too, it has few peers. Though it does not yet

have a semiconductor industry that quite matches those elsewhere, it is world

class in many applications, especially in artificial intelligence.

The same applies in

trendy bits of biology. The above mentioned Dr He was not the first person to

edit the DNA of a human embryo. That honour belongs

to Huang Junjiu, a researcher at Sun Yat-sen

University, in Guangzhou, whose research was blameless and above-board. Like Dr

He, Dr Huang was making use of the capabilities of CRISPR-Cas9. Since 2012 this

form of gene editing has become one of the hottest fields in biology, and China

is very well represented in it (see chart 4); according to the study by Elsevier

and Nikkei, it is publishing 22.6% of the world’s most highly cited papers in

gene editing, slightly more than half the amount that comes from America, and

far more than from any other country.

Dr

Huang wants to apply CRISPR-Cas9 to the treatment of beta thalassemia, a

hereditary blood disease. To this end, in 2015 he successfully edited the DNA

of several fertilized human eggs left over from IVF treatment. He had no

intention of implanting the results in anybody’s womb; he used embryos which,

due to other abnormalities, were not able to develop. What he learned about

gene editing in those experiments will, if all goes well, be used to edit

stem-cells extracted from the bone marrow of people suffering from the disease,

allowing them to make better red blood cells.

Stem-cell research is

another hot topic to which China is adding its heft. Zuo Wei of Tongji

University in Shanghai is trying to

use stem cells to repair lungs damaged by emphysema, a big problem in

China, where smoking is still common and the air often dense with smog. Last

year he conducted a trial in which four patients had some lung tissue removed.

The most healthy-looking stem cells in that tissue were isolated and encouraged

to multiply, and the revved-up results then sprayed back into the lung. The

procedure apparently repaired the lungs of two of the patients; the other two

showed neither benefits nor harm. Dr Zuo has since organized a second trial of

100 patients. He is working on a similar approach to kidney disease, but so far

only in mice.

Let 100,000 genomes bloom

Dr Zuo’s work

demonstrates another feature of Chinese bioscience: keeping its application

clearly in mind. In the West, there has been an increasing concern over the

past couple of decades that basic biology led by independent academic

researchers has drifted too far from the potential medical application. In

America, in particular, biomedical-research prowess and the health of the

population are increasingly poorly correlated.

This concern has led to

a new emphasis on building up “translational-medicine” research capacities to

bridge the gap—an idea the Chinese are already integrating into their work. The

government has opened a translational-medicine center in Shanghai, where

laboratory researchers, clinicians, and patients will all be under the same

roof and biotech companies encouraged to set up shop next door. Others may

follow in Beijing, Chengdu, and Xi’an.

Genetic research is a

field where China has both made big investments and sees a big future. In the

BGI, as what was once the Beijing Genomics Institute is now known, China has by some

measures the largest genome-sequencing center in the world. Once an arm of

CAS, it declared independence as a “citizen-managed, non-profit research

institution” and has now become a semi-commercial chimera, with one of its

divisions listed as a company on the Shenzhen stock exchange.

The BGI’s corporate

arm is also taking an interest in beta-thalassemia; it has developed a DNA

blood test for it, one of an increasing range it is making available across

China. The tests use DNA-sequencing machines the BGI developed with technology

which it acquired when it bought Complete Genomics, an American firm, in 2013.

That battalion of

machines has a lot of other work to do. Non-commercial bits of the BGI use them

for pure research. The outfit is also home to the China National GeneBank, the intended repository for several hundred

million samples taken from living creatures of all sorts, human and non-human.

It already holds the genomes of 140,000 Chinese people, part of a wider desire

by the government to be at the forefront of the field of precision medicine, in

which diagnoses, and eventually treatments, are personalized with particular

emphasis on understanding a patient’s genetic make-up.

The BGI is one

example of China’s ability to bring big-science approaches to new areas of

research. For another, you should look inside a low building in Zhuanghe, Liaoning province, where the world’s largest

battery is taking shape. It is to have six times the storage capacity of the

system supplied by Elon Musk, an American entrepreneur, to South Australia in

2017, which lashed together thousands of lithium-ion battery cells to make the

world’s then-largest battery. It can do so because it uses a completely

different approach based on a flow of vanadium-salt solutions.

China’s

near-insatiable demand for energy has led to investments in wind and solar

power that dwarf those in other parts of the world and is now leading to

research into better ways of handling the energy they produce. Vanadium-flow

batteries are of interest because, unlike most batteries, in which a single

electrolyte is built into the cell, a flow battery has two electrolytes and an

open cell through which they pass. This means its storage capacity is governed

solely by the size of the tanks that store the electrolytes. That makes it

possible, in theory, to build batteries big enough to store energy on a scale

useful to large grids. The theory has been developed by Zhang Huamin, a researcher at the Dalian Institute of Chemical

Physics, a local arm of CAS. The factory in Zhuanghe,

owned by Dalian Rongke Power, a local electricity

company, is trying to turn theory into practice. If it works, it could

revolutionize grid-scale electricity storage.

The Dalian

Institute’s researchers are also looking into perovskites, materials with

applications both in batteries and in solar cells. Their aim—also being pursued

elsewhere in China and abroad—is to apply perovskite solutions to everyday

solar cells so that the resultant layers will absorb wavelengths of light that

the normal cells cannot absorb. This could produce much more efficient solar

panels for the relatively little extra cost. To the extent that academic

publications are a good measure of technologies quite close to the market,

perovskites are an area where China has a substantial lead over America, with

41.4% of the highest impact publications, compared with 21.5% from America.

Taking things on trust

China’s energy

research also extends to areas that the rest of the world is avoiding. China is

building 13 new nuclear reactors to add to its fleet of 45; it has 43 more

planned. If they are all built China will

become the world’s biggest generator of nuclear electricity. Those reactors

are of similar design to the plants already in operation around the world. But

China is also exploring new reactor technologies--or rather, technologies

abandoned elsewhere. These include reactors in which the core is filled not

with fuel rods but with little ceramic pebbles--or, in the case of thorium

reactors, with molten metal.

The lack of progress

such reactors have enjoyed in the West reflects a lack of appetite for new

sorts of nuclear power much more than a lack of scientific plausibility. If

China’s appetite is sharp and its researchers imaginative, progress may come

swiftly. The development of mass-produced, compact, cheap and safe nuclear

reactors would be a Chinese first that a world in the throes of climate change

would have real cause to celelebrate--and start

importing.

That possibility,

though, brings to the fore a shadow over the future of Chinese science. Making

novel nuclear reactors extremely safe requires critical thinking and obstinate

truth-telling; so does convincing others that you have done so. A culture that

provides the results the boss wants, or does not investigate inconvenient

anomalies, or withholds data from nosy outsiders is not good enough.

Those requirements

are very like the norms that are seen as basic to doing good science in the

West. Testing hypotheses, finding the flaws in the work on which your teacher’s

reputation rests, questioning your own assumptions, following the data wherever

they lead, sharing data openly with your rivals-sorry-colleagues: this is how

science is meant to work, even if in real life the ideal can be a bit

tarnished. In some labs and institutions in China things doubtless do work that

way. But the authoritarian system in which they are embedded makes it hard for

Chinese science to speak truth to power, or escape challenges to its integrity.

This gnaws at the scientific body politic, and saps resources, both financial

and moral.

In their survey of

Chinese researchers Dr Han and Dr Appelbaum heard many complaints about

excessive government interference. A respondent from Sun Yat-sen University

told them “There

is still not enough academic freedom in higher education. If the central

government makes one statement, even if it is not fair, all of the universities

have to follow suit.”

In matters of

promotion, job interviews and grant-giving, the question of who you know seems

much more important in China than in the West (and even there, it is not

negligible). For the past decade the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (NNSFC), one of the country’s main funding bodies, has been running a

campaign against such misconduct. Wei Yang, until recently the NNSFC’s boss,

describes a situation in which, to stop interference from outside, the

composition of interview panels is kept secret until the last minute. Panellists are not told in advance who candidates are, and

both panellists and candidates have their mobile

phones confiscated in order to avoid anyone being nobbled--which used to happen

even while interviews were being conducted.

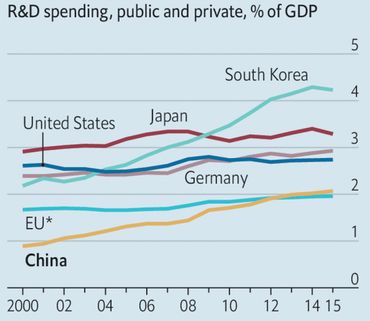

Some Chinese

scientists fear that the corruptions and silences endemic in authoritarian

states will hold them back from the breakthrough-making Nobel-winning heights.

Others may doubt this. China has been playing in science’s premier league for

only a decade or so. Its investments are not at an end. China’s R&D was

2.07% of GDP in 2015, up from 0.89% in 2000 (see chart 5). That is higher than

the average for European states, but lower than France, Germany or America. It

is much lower than in the Asian catch-up states that might be the most natural

comparators, Japan and South Korea. A China spending as much of its GDP on

research as South Korea does would have an R&D budget twice today’s. With

resources on that scale and a scientific workforce in the many millions, the

hobbling effect of corrupt institutions might be overcome by brute force.

Others might argue

that big breakthroughs are not the only measure of good science. Incremental

work that solves practical problems is not to be sniffed at. Scientific

research directed from the top down can serve national goals, and a one-party

system may give particularly consistent support to such programmes.

China’s lunar programme has built up its capabilities

steadily in a way no Western space-science programme

has since Apollo, the achievements of which it may yet match.

This is the sort of

methodical science that typically appeals to engineers oriented towards

results--and from Jiang Zemin onwards all China’s presidents, as well as almost

all its other leading politicians, have had engineering degrees. Xi Jinping,

today’s president, studied chemical engineering at Tsinghua.

But the idea that you

can get either truly reliable science or truly great science in a political

system that depends on a culture of unappealable authority is, as yet,

unproven. Perhaps you can. Perhaps you cannot. And perhaps, in trying to do so,

you will discover new ways of thinking as well as fruitful knowledge.

Will the restoration of Science also lead to a greater

space for Democracy?

Xi talks of science

and technology as a national project. However, in most scientific research

today, chauvinism is a handicap. Expertise, good ideas, and creativity do not

respect national frontiers. Research takes place in teams, which may involve

dozens of scientists. Published papers get you only so far: conferences and

face-to-face encounters are essential to grasp the subtleties of what everyone

else is up to. There is competition, to be sure; military and commercial

research must remain secret. But pure science thrives on collaboration and

exchange.

This gives Chinese

scientists an incentive to observe international rules--because that is what

will win its researcher's access to the best conferences, laboratories and

journals, and because unethical science diminishes China’s soft power. Dr He’s

gene-editing may well be remembered not just for his ethical breach, but also

for the furious condemnation he received from his Chinese colleagues and the

threat of punishment from the authorities. The satellite destruction in 2007

caused outrage in China. It has not been repeated.

The tantalizing

question is how this bears on Democracy. Nothing says the best scientists have

to believe in political freedom. And yet critical thinking, skepticism,

empiricism and frequent contact with foreign colleagues threaten

authoritarians, who survive by controlling what people say and think. Soviet

Russia sought to resolve that contradiction by giving its scientists privileges

but isolating many of them in closed cities.

China will not be

able to corral its rapidly growing scientific elite in that way. Although many

researchers will be satisfied with just their academic freedom, only a small

number need to seek broader self-expression to cause problems for the Communist

Party. Think of Andrei Sakharov, who developed the Russian hydrogen bomb, and

later became a chief Soviet dissident; or Fang Lizhi, an astrophysicist who

inspired the students leading the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. When the

official version of reality was tired and stilted, both stood out as seekers of

the truth. That gave them immense moral authority.

Some in the West may

feel threatened by China’s advances in science and therefore aim to keep its

researchers at arm’s length. That would be wise for weapons science and

commercial research, where elaborate mechanisms to preserve secrecy already

exist and could be strengthened. But to extend an arms-length approach to

ordinary research would be self-defeating. Collaboration is the best way of

ensuring that Chinese science is responsible and transparent. It might even

foster the next Fang.

Hard as it is to imagine,

President Xi Jinping could end up facing a much tougher choice: to be content

with lagging behind, or to give his scientists the freedom they need and risk

the consequences. In that sense, he is running the biggest experiment of all.

For

updates click homepage here