By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

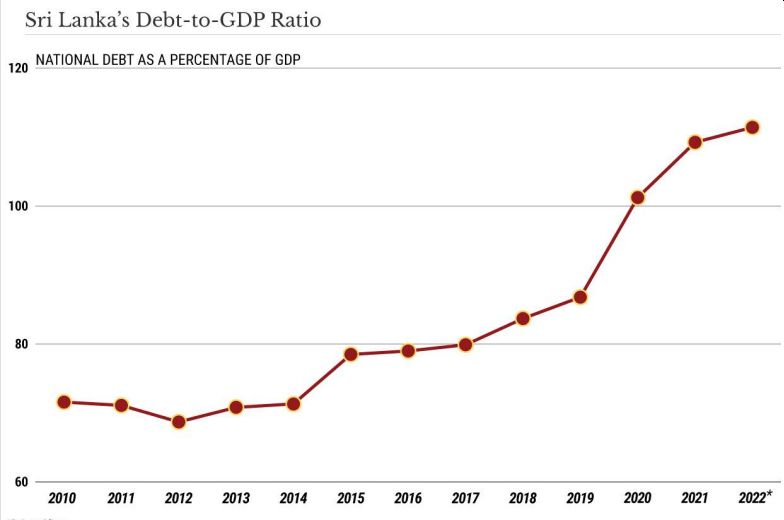

Already in 2018, we pointed out that Sri Lanka's desperately

under-utilized Hambantota Port had to be surrendered to Chinese operators in a

humiliating example of debt-trap diplomacy.

More recently, China has dispatched a military ship to Sri Lanka's port

city of Hambantota amid the rapidly changing political situation in the island

nation. The move has raised questions about whether China is trying to

establish a robust military presence on Sri Lanka's Indian Ocean coast.

Yet Sri Lanka asked China to defer the planned visit of the ship, as it

was objected

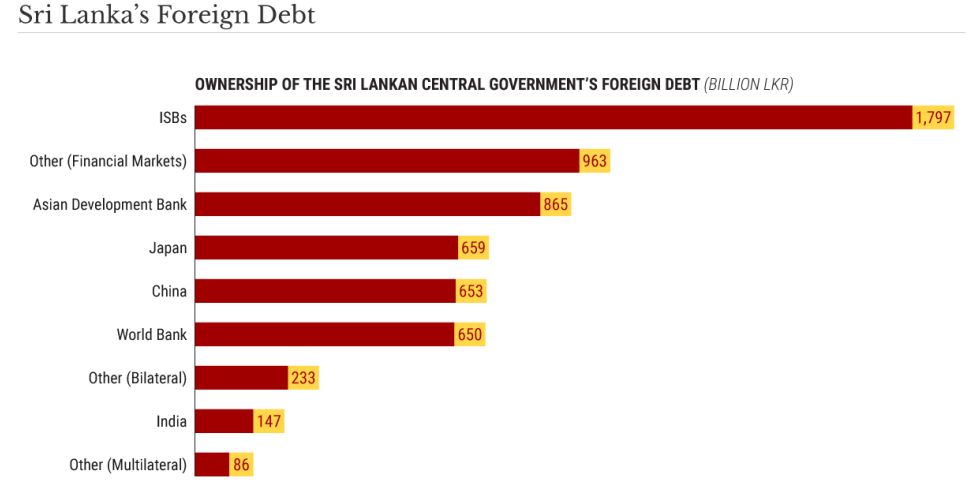

to by India. That is worrying that the Chinese-built and leased China

will use the port of Hambantota as a military base in India's backyard. Not to

mention that India recently emerged as the top lender to Sri Lanka,

extending USD 376.9 million worth of credit compared to USD 67.9 million by

China in the first four months of this year.

China won Sri Lanka’s earlier trust because of its willingness to lend

money to countries shunned by the international community for their poor human

rights records. Indeed, their relationship strengthened after allegations

emerged in Sri Lanka of state-sponsored human rights abuses during the Tamil Tigers-led insurgency in the country.

China’s Motivations

What’s in it for

Beijing? China has been investing massively in infrastructure and other

projects in nearby countries, primarily because this helps guarantee its access

to foreign markets through key regional maritime routes. These investments are

a substantial source of Chinese influence in the region.

In addition, Sri

Lanka is significant in China’s “string of pearls” strategy in the Indian

Ocean. The port of Hambantota, operated as a joint venture and currently leased

to China for 99 years, straddles a bustling east-west shipping route. It offers

a diversified range of transport and logistical services. China has a strategic

imperative to gain immediate access to India.

Ocean and control

ports in the Asia-Pacific region so that it can conduct trade and maintain

strong relations with its numerous partners. Hambantota is close to major sea

lanes, so building a port there could help Beijing guarantee access to

international trade routes nearby.

However, China hasn’t

been enthusiastic about coming to its ally’s aid. It even refused to

restructure Sri Lanka’s debt when asked. On the other hand, India was the first

to provide immediate help with a $1.5 billion line of credit. A line of credit

may not be ideal given Sri Lanka’s situation, but right now, it needs whatever

help it can get. New Delhi’s offer is an attempt to pry the island nation away

from Beijing– not surprising since India is trying to counter China in the

Indo-Pacific region, where the two regional powers have competing interests.

For India, wooing one of China’s “pearls” would be a big step.

China’s hesitancy in

helping Sri Lanka is a result of domestic constraints. The East Asian country

is facing its structural economic problems and has been battling an outbreak of

the omicron COVID-19 variant for months, which has led to partial or complete

lockdowns of significant cities, including its financial hub, Shanghai. Given

that Beijing spent weeks considering whether to provide Sri Lanka with

financial assistance, it seemed that China was unwilling or unable to help.

On April 25, however,

talks between the two countries began after Chinese Premier Li Keqiang said

China was ready to provide much-needed assistance for Sri Lanka. But many in

Sri Lanka see this as an empty promise that came too late and only as a

response to Sri Lanka’s talks with the IMF. Doubts about China’s credibility

aren’t surprising, given that Sri Lanka in the past has had to find new

financing for BRI projects after China failed to come through with promised

funds on time.

Waiting in the Wings

China’s role in helping

Sri Lanka resolve its economic crisis is important because it will set a

precedent for other countries in South and Southeast Asia that may also face

financial difficulties soon. Also, China’s global image is in part based on its

ability to assist and invest in smaller neighboring countries, so if Beijing

fails to come through, it could cast a negative light on its international

standing.

Moreover, as seen

with India, other powers are waiting in the wings to fill the void left by

Beijing. China’s failure to act opens the door for other nations that want to

counter Chinese influence in the region. And Sri Lanka has no choice but to

rely on its largest creditors, many of which have an interest in strengthening

China’s regional influence.

India, as mentioned,

is one example, but Japan is another potential source of financial assistance.

It has historically been a significant source of development aid for Sri Lanka

and offered help during the country’s last economic crisis in 2016.

The U.S. has also

provided financial assistance to countries in the region and may welcome an

opportunity to undermine China here. Furthermore, Sri Lanka expects to receive

$500 million as emergency aid from the Asian Development Bank and World Bank –

two institutions affiliated with countries that have an interest in countering

Chinese influence –in the next six months.

Much depends on

China’s handling of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis. It’ll have to give up

something significant, money, or influence.

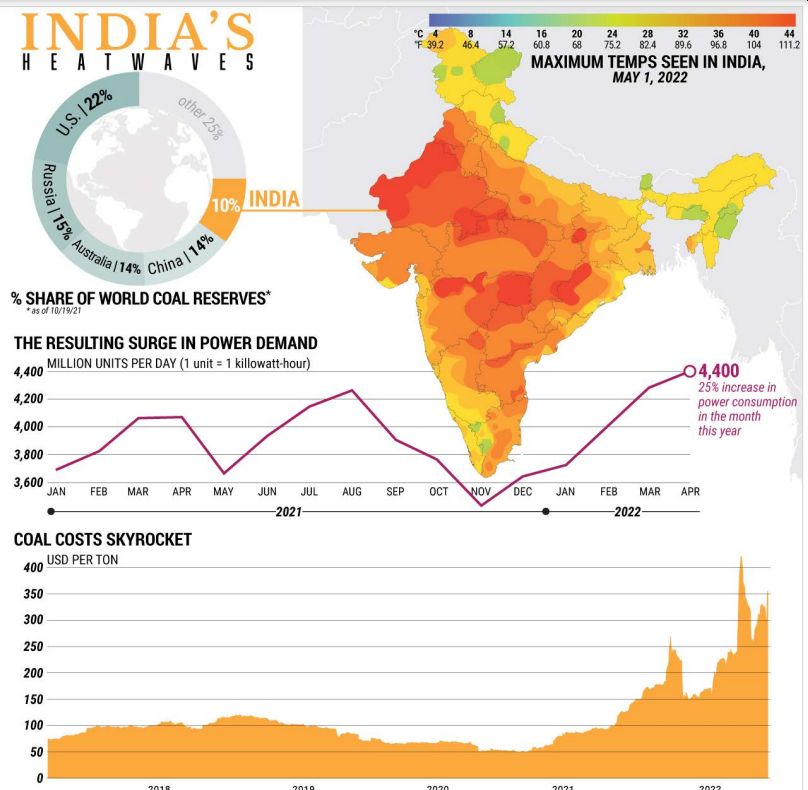

Energy disruptions are threatening

India’s economic recovery.

Although India has

some of the world’s largest coal reserves, its massive power consumption means

importing coal to meet its energy needs. India is facing a two-part coal

conundrum:

Supply shortages and

rising prices. Oil and natural gas prices were already rising as economies

across the globe came back online from the pandemic. Between the recovery and

the price hikes provoked by Russia’s invasion of

Ukraine, many countries turned to cheaper energy alternatives, including

coal. This, in turn, pushed up coal prices.

The situation

concerns the Indian economy on several fronts; power demand was well above peak

consumption last summer, and power plants are now in a weaker position to meet

upcoming summer demand.

Coal shortages and

slumping inventories have created electricity shortages in major Indian cities,

including New Delhi, where hospitals have been affected. Sixty percent of

households in India have already experienced daily power cuts. The government

plans to increase domestic coal output and reduce coal supplies to the

non-power sector. The supply cuts will affect aluminum smelters, steel mills,

and other industrial activities, risking the country’s economic recovery.

For updates click hompage here