By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

On 17 May we reported that the US

director of national intelligence said China was seeking the military

capability to conquer Taiwan, even if the US intervened. Where today the

South China Post reports that Beijing is likely to step up its campaign to

‘reunify’ with Taiwan and that China ‘will

soon be equipped with the tools needed to attack. The Japan Times adds

that the

U.S. rejects China’s claims over Taiwan Strait and an armed conflict

seen as higher than five years ago as PLA ‘will soon be equipped with the tools

needed to attack.

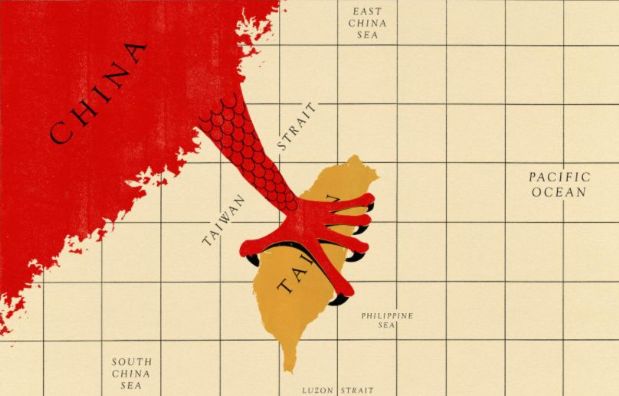

If the intractable issues could spark a hot war between the United

States and China, Taiwan is at the top of the list. And the potential

geopolitical consequences of such a war would be profound. Taiwan—“an

unsinkable aircraft carrier and submarine tender,” as U.S. Army General Douglas

MacArthur once described it—has significant, often underappreciated military

value as a gateway to the Philippine Sea, a vital theater for defending Japan,

the Philippines, and South Korea from possible Chinese coercion or attack.

There is no guarantee that China would win a war for the island—or that such a

conflict wouldn’t drag on for years and weaken China. But if Beijing gained

control of Taiwan and based military assets there, China’s military position

would improve markedly.

In particular, Beijing’s ocean surveillance assets and submarines could

take control of Taiwan, a substantial boon to Chinese military power. Even

without any significant technological or military leaps, possession of the

island would improve China’s ability to impede U.S. naval and air operations in

the Philippine Sea and thereby limit the United States’ ability to defend its

Asian allies. And if, in the future, Beijing were to develop a large fleet of

quiet nuclear attack submarines and

ballistic missile submarines, basing them on Taiwan would enable China to

threaten Northeast Asian shipping lanes and strengthen its sea-based atomic

forces.

The island’s military value bolsters the argument for keeping Taiwan out of China’s grasp.

However, the strength of that case depends on several factors, including

whether one assumes that China would pursue additional territorial expansion

after occupying Taiwan and make the long-term military and technological

investments needed to take full advantage of the island. It also depends on the

broader course of U.S. China policy. Washington could remain committed to its current

approach of containing the expansion of Chinese power through a combination of

political commitments to U.S. partners and allies in Asia and a significant

forward military presence. Or it might adopt a more flexible policy that

retains obligations only to core treaty allies and reduces forward-deployed

forces. Or it might reduce all such commitments as part of a more restrained

approach. Regardless of which of these three strategies the United States

pursues, Chinese control of Taiwan would limit the U.S. military’s ability to

operate in the Pacific and potentially threaten U.S. interests.

But the issue is not just that Taiwan’s tremendous military value poses

problems for any U.S. grand strategy. It is that no matter what Washington

does—whether it attempts to keep Taiwan out of Chinese hands or not—it will be

forced to run risks and incur costs in its standoff with Beijing. As the place

where all the dilemmas of U.S. policy toward China collide, Taiwan presents one

of the world’s most challenging and dangerous problems. Put, Washington has few

good options there and a great many bad ones that could court calamity.

Taiwan in the balance

A Chinese assault on Taiwan could shift the military balance of power

in Asia in various ways. If China were to take the island swiftly and

efficiently, many of its military assets geared toward a Taiwan campaign might

be freed up to pursue other military objectives. China might also be able to

assimilate Taiwan’s strategic resources, such as its military equipment, personnel,

and semiconductor industry, all of which would bolster Beijing’s military

power. But if China were to find itself bogged down in a prolonged conquest or

occupation of Taiwan, the attempt at forced unification might become a

significant drag on Beijing’s might.

However, any campaign that delivers Taiwan to

China would allow Beijing to base critical military hardware there—particularly

underwater surveillance devices and submarines, along with associated air and

coastal defense assets. Stationed in Taiwan, these assets would do more than

extend China’s reach eastward by the length of the Taiwan Strait, as would be

the case if China-based missiles, aircraft, unmanned aerial vehicles, or other

weapons systems were on the island. Underwater surveillance and submarines, by

contrast, would improve Beijing’s ability to impede U.S. operations in the

Philippine Sea. This area would be vital in many possible future conflict

scenarios involving China.

The most likely scenarios revolve around the United States defending its allies along the

so-called first island chain off the Asian mainland, which starts north of

Japan and runs southwest through Taiwan and the Philippines before curling up

toward Vietnam. For example, U.S. naval operations in these waters would be essential

to protecting Japan against potential Chinese threats in the East China Sea and

at the southern end of the Ryukyu Islands. Such U.S. operations would also be

important in most scenarios for defending the Philippines and for any scenario

that might lead to U.S. strikes on the Chinese mainland, such as a significant

conflagration on the Korean Peninsula. U.S. naval operations in the Philippine

Sea will become even more important as China’s growing missile capabilities

render land-based aircraft and their regional bases increasingly vulnerable,

forcing the United States to rely more heavily on aircraft and missiles

launched from ships.

Suppose a war in the Pacific were to break out today. In that case,

China’s ability to conduct effective over-the-horizon attacks targeting U.S.

ships at distances that exceed the line of sight to the horizon would be more

limited than commonly supposed. China might be able to target forward-deployed

U.S. aircraft carriers and other ships in a first strike that commences a war.

But once a conflict is underway, China’s best surveillance assets—large radars

on the mainland that allow China to “see” over the horizon—are likely to be

quickly destroyed. The same is true of Chinese surveillance aircraft or ships

in the vicinity of U.S. naval forces.

Chinese satellites would be unlikely to make up for these losses. Using

techniques the United States honed during the Cold War, U.S. naval forces would

probably be able to control their radar and communications signatures and

thereby avoid detection by Chinese satellites that listen for electronic

emissions. Without intelligence from these specialized signal-collecting

assets, China’s imaging satellites would be left to search vast ocean swaths

for U.S. forces randomly. Under these conditions, U.S. forces operating in the

Philippine Sea would face real but tolerable risks of long-range attacks. U.S.

leaders probably would not feel immediate pressure to escalate the conflict by

attacking Chinese satellites.

However, if China were to wrest control of Taiwan, the situation would

look quite different. China could place underwater microphones called

hydrophones in the waters off the island’s east coast, much deeper than the

waters Beijing currently controls inside the first island chain. Placed at the

appropriate depth, these specialized sensors could listen outward and detect

the low-frequency sounds of U.S. surface ships thousands of miles away,

enabling China to locate them with satellites and target them with missiles

more precisely. (U.S. submarines are too quiet for these hydrophones to

detect.) Such capabilities could force the United States to restrict its

surface ships to areas outside the range of the hydrophones—or else carry out

risky and escalators attacks on Chinese satellites. Neither of these options is

appealing.

Chinese hydrophones off Taiwan would be difficult for the United States

to destroy. Only highly specialized submarines or unmanned underwater vehicles

could disable them, and China would be able to defend them with a variety of

means, including mines. Even if the United States damaged China’s hydrophone

cables, Chinese repair ships could mend them under cover of air defenses China

could deploy on the island.

The best hope for disrupting Chinese hydrophone surveillance would be

to attack the vulnerable processing stations where the data comes ashore via

fiber-optic cables. But those stations could prove hard to find. The cables can

be buried on land and under the sea, and nothing distinguishes the buildings

where data processing is done from similar nondescript military buildings. The

range of possible U.S. targets could include hundreds of individual structures

inside multiple well-defended military locations across Taiwan.

However, control of Taiwan would do more than enhance Chinese ocean

surveillance capabilities. It would also give China an advantage in submarine

warfare. With Taiwan in friendly hands, the United States can defend against

Chinese attack submarines by placing underwater sensors in critical locations

to pick up the sounds the submarines emit. The United States likely deploys

such upward-facing hydrophones—for listening to shorter distances—along the

bottom of narrow chokepoints at the entrances to the Philippine Sea, including

in the gaps between the Philippines, the Ryukyu Islands, and Taiwan. These

instruments can briefly detect even the quietest submarines at such close

ranges, allowing U.S. air and surface assets to trail them. During a crisis,

that could prevent Chinese submarines from getting a “free shot” at U.S. ships

in the early stages of a war, when forward-deployed U.S. naval assets would be

at their most vulnerable.

If China were to gain control of Taiwan, however, it would be able to

base submarines and support air and coastal defenses on the island. Chinese

submarines would then be able to slip from their pens in Taiwan’s eastern

deep-water ports directly into the Philippine Sea, bypassing the chokepoints

where U.S. hydrophones would be listening. Chinese defenses on Taiwan would

also prevent the United States and its allies from using their best tools for

trailing submarines—maritime patrol aircraft and helicopter-equipped ships—near

the island, making it much easier for Chinese submarines to strike first in a

crisis and reducing their attrition rate in a war. Control of Taiwan would have

the added advantage of reducing the distance between Chinese submarine bases

and their patrol areas from an average of 670 nautical miles to zero, enabling

China to operate more submarines at any given time and carry out more attacks

against U.S. forces. Chinese submarines could also use the more precise

targeting data collected by hydrophones and satellites, dramatically improving

their effectiveness against U.S. surface ships.

Under the sea

Over time, unification with Taiwan could offer China even more

significant military advantages if it invested in a fleet of much quieter

advanced nuclear attack and ballistic

missile submarines. Operated from Taiwan’s east coast, these submarines would

strengthen China’s nuclear deterrent and allow it to threaten Northeast Asian

shipping and naval routes in the event of a war.

China’s submarine force is currently poorly equipped to campaign

against U.S. allies’ oil and maritime trade. Global shipping has traditionally

proved resilient in the face of such threats because it is possible to reroute

vessels outside the range of hostile forces. Even the closure of the Suez Canal

between 1967 and 1975 did not paralyze global trade since ships were instead

able to go around the Cape of Good Hope, albeit at some additional cost. This

resiliency means that Beijing would have to target shipping routes as they

migrated north or west across the Pacific Ocean, likely near ports in Northeast

Asia. But most of China’s current attack submarines are low-endurance

diesel-electric boats that would struggle to operate at such distances. In

contrast, a few longer-endurance nuclear-powered submarines that are noisy and

thus vulnerable to detection by U.S. outward-facing hydrophones could be

deployed along the so-called second island chain, which stretches southeast

from Japan through the Northern Mariana Islands and past Guam.

Similarly, China’s current crop of ballistic missile submarines does

little to strengthen China’s nuclear deterrent. The ballistic missiles they

carry can at best target Alaska and the northwest corner of the United States

when launched within the first island chain. And because the submarines are

vulnerable to detection, they would struggle to reach open ocean areas where

they could threaten the rest of the United States.

Even a future Chinese fleet of much quieter advanced nuclear attack or

ballistic missile submarines capable of evading outward-facing hydrophones

along the second island chain would still have to pass over U.S. upward-facing

hydrophones nestled at the exits to the first island chain. These barriers

would enable the United States to impose substantial losses on Chinese advanced

nuclear attack submarines going to and from Northeast Asian shipping lanes and

significantly impede the missions of Chinese ballistic missile submarines, of

which there would certainly be fewer.

But if it were to acquire Taiwan, China could avoid U.S. hydrophones

along the first island chain, unlocking the military potential of quieter

submarines. These vessels would have direct access to the Philippine Sea and

the protection of Chinese air and coastal defenses, which would keep trailing

U.S. ships and aircraft at bay. A fleet of quiet nuclear attack submarines

deployed from Taiwan would also have the endurance to campaign against

Northeast Asian shipping lanes. And a fleet of quiet ballistic missile

submarines with access to the open ocean would enable China to more credibly

threaten the continental United States with a sea-launched nuclear attack.

Of course, it remains to be seen whether China can master more advanced

quieting techniques or solve several problems that have plagued its

nuclear-powered submarines. And the importance of the anti-shipping and

sea-based nuclear capabilities is open for debate since their relative impact

will depend on what other qualifications China does or doesn’t develop and what

strategic goals China pursues in the future. Still, the behavior of past great

powers is instructive. Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union both invested heavily

in attack submarines, and the latter made a similar investment in ballistic

missile submarines. The democratic adversaries of those countries felt deeply

threatened by these undersea capabilities and mounted enormous efforts to

neutralize them. A Chinese seizure of Taiwan would thus offer Beijing the kind

of military option that previous great powers found very useful.

No good options

A fuller understanding of Taiwan’s military values bolsters the

argument in favor of keeping the island in friendly hands. Yet just how

decisive that argument should depend, in part, on what overall strategy the

United States pursues in Asia. And whatever approach Washington adopts, it will

have to contend with challenges and dilemmas stemming from the military advantages

that Taiwan has the potential to confer on whoever controls it.

If the United States maintains its current strategy of containing

China, retaining its network of alliances, and

forward military presence in Asia, defending Taiwan could be extremely costly.

After all, the island’s military value gives China a strong motive for seeking

unification beyond the nationalist impulses most commonly cited. Deterring

Beijing would, therefore, probably require abandoning the long-standing U.S.

policy of strategic ambiguity about whether Washington would come to the

island’s defense in favor of a crystal-clear commitment of military support.

But ending strategic ambiguity could provoke the very crisis the policy

is designed to prevent. It would undoubtedly heighten pressures for an arms

race between the United States and China in anticipation of a conflict,

intensifying the already dangerous competition between the two powers. And even

if a policy of strategic clarity were successful in deterring a Chinese attempt

to take Taiwan, it would likely spur China to compensate for its military

disadvantages in some other way, further heightening tensions.

Alternatively, the United States might pursue a more flexible security

perimeter that eliminates its commitment to Taiwan while retaining its treaty

alliances and some forward-deployed military forces in Asia. Such an approach

would reduce the chance of a conflict over Taiwan, but it would carry other

military costs, again owing to the island’s military value. U.S. forces would

need to conduct their missions in an arena made much more dangerous by Chinese

submarines and hydrophones deployed off the east coast of Taiwan. As a result,

the United States might need to develop decoys to deceive Chinese sensors,

devise ways to operate outside their normal range or prepare to cut the cables

that connect these sensors to onshore processing centers in the event of war.

Washington would undoubtedly want to ramp up its efforts to disrupt Chinese

satellites.

Should the United States take this approach, reassuring U.S. allies

would become a much more arduous task. Precisely because control of Taiwan

would grant Beijing significant military advantages, Japan, the Philippines,

and South Korea would likely demand strong demonstrations of a continuing U.S.

commitment. Japan, in particular, would be inclined to worry that a diminished

U.S. ability to operate on the surface of the Philippine Sea would translate

into enhanced Chinese coercion or attack capability, especially given the

proximity of Japan’s southernmost islands to Taiwan.

Over the longer term, U.S. allies in the region would also likely fear

the growing Chinese threat to shipping routes and worry that a stronger

sea-based Chinese nuclear deterrent would reduce the credibility of U.S.

commitments to defend them from attack. Anticipation of these dangers would

almost certainly drive U.S. allies to seek greater reassurance from the United

States in the form of tighter defense pacts, additional military aid, and more

visible U.S. force deployments in the region, including nuclear forces on or

near allies’ territory and perhaps collaborating with their governments on

nuclear planning. East Asia could look much like Europe did in the later stages

of the Cold War, with U.S. allies demanding demonstrations of their U.S.

patron’s commitment in the face of doubts about the military balance of power.

If the Cold War is any guide, such steps could heighten the risks of nuclear

escalation in a crisis or a war.

Finally, the United States might pursue a strategy that ends its

commitment to Taiwan and reduces its military presence in Asia and other

regional alliance commitments. Such a policy might limit direct U.S. military

support to the defense of Japan or even wind down all U.S. commitments in East

Asia. But even in this case, Taiwan’s potential military value to China would

still have the potential to create dangerous regional dynamics. Worried that

some of its islands might be next, Japan might fight to defend Taiwan, even if

the United States did not. The result might be a major-power war in Asia that

could draw in the United States, willingly or not. Such a war would be

devastating. Yet upsetting the current delicate equilibrium by ceding this

militarily valuable island could make such a war more likely, reinforcing a

core argument in favor of the current U.S. grand strategy: that U.S. alliance

commitments and forward military presence exert a deterring and constraining

effect on the conflict in the region.

Ultimately, however, Taiwan’s unique military value poses problems for

all three U.S. grand strategies. Whether the United States solidifies its

commitment to Taiwan and its allies in Asia or walks them back, in full or in

part, the island’s potential to alter the region’s military balance will force

Washington to confront difficult tradeoffs, ceding military maneuverability in

the region or else risking an arms race or even an open conflict with China.

Such is the corrupt nature of the problem posed by Taiwan, which sits at the

nexus of U.S.-Chinese relations, geopolitics, and the military balance in Asia.

Regardless of Washington’s grand strategy, the island’s military value will

present some hazard or exact some price.

For updates click hompage here