Having just covered; Where will the China/US

competition lead the world?

Taking this research

in the direction of SEAsia, it appears that rust in

the United States has risen among Southeast Asian policymakers over the past

year while trust in China has fallen, according to an annual survey of regional opinion conducted by

Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

The interesting

question is the extent to which the more positive perceptions of the U.S.

result from a temporary “Biden bump” or reflect a more permanent shift in

perceptions. As the report's authors wrote, “Only time will tell if the

region’s renewed trust in the U.S. is misplaced or not.”

Also, a poll of more than 1,000 Southeast Asian experts, analysts, and

business leaders has laid bare the concerns of a region trying to find its way

amid the rise of China and the decline of the United States’ influence.

On the one hand, many

in the region are wary of President Xi Jinping’s mission to reclaim for China

the centrality it enjoyed in East Asia before the imperial depredations by the

West and Japan in the 19th

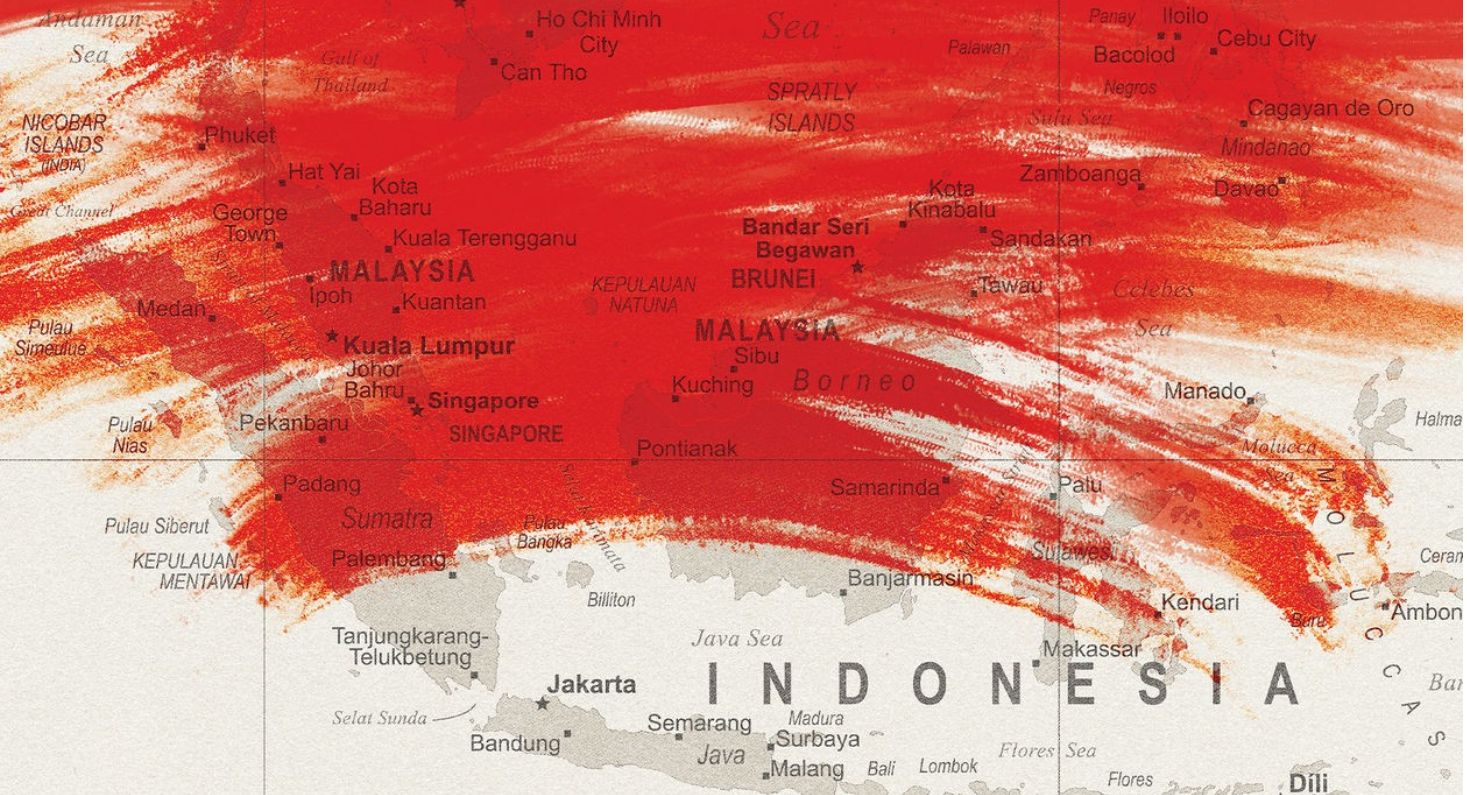

and early 20th century. It is not just that China is aggressively

challenging the maritime and

territorial claims of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines,

and Vietnam in the South China Sea, through which the majority of China’s

seaborne trade passes. It is also that Xi’s call for “Asian people to run the

affairs of Asia” sounds like code for China running Asia. As a Chinese foreign

minister once told a gathering of the ten-country Association of South-East

Asian Nations (ASEAN): “China is a big

country and [you] are small countries, and that is just a fact.”

On the other hand,

while ASEAN members welcome America as the dominant military power in the

region to counter China’s growing heft, they know that conflict would be

disastrous for them. South-East Asian diplomats did not loudly cheer the

anti-China rhetoric of President Donald Trump’s administration, which is

unlikely to soften much under Joe Biden. And no wonder. Many of the region’s

governments are hostile to democracy, and few see America’s political model as

one to emulate.

People across

South-East Asia already see America and China as two poles, pulling their

countries opposite directions. Those protesting against the recent military

coup in Myanmar, for example, hold up angry placards that attack China for

backing the generals and pleading ones that beg America to intervene.

Governments feel under pressure to pick sides. In 2016 Rodrigo Duterte, the

Philippines president, loudly announced his country’s “separation from America”

and pledged allegiance to China. China’s claim that almost all the South China

Sea lies within its territorial waters and America’s rejection of that

assertion has sparked blazing rows in the main regional club, the Association

of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), which China has attempted to win over.

This tug-of-war will

only become more fierce for two reasons. First, South-East Asia is of enormous

strategic importance to China. On China’s doorstep, astride the trade routes

along which oil and other raw materials are transported to China, and finished

goods are shipped out. Whereas China is hemmed into its east by Japan, South

Korea, and Taiwan, all firm American allies, South-East Asia, are less hostile

terrain, providing potential access to both the Indian and Pacific Oceans for

commercial and military purposes. Only by becoming the pre-eminent power in

South-East Asia can China relieve its sense of claustrophobia.

But South-East Asia

is not just a way-station en route to other places.

The second reason competition over it will intensify is that it is an ever more

important part of the world in its own right. It is home to 700m people, more

than the European Union, Latin America, or the Middle East. Its economy, a

single country, would be the fourth-biggest in the world after adjusting for

the cost of living, behind only China itself, America, and India. And it is

growing fast. Indonesia and Malaysia's economies have been expanding by 5-6%

for a decade; those of the Philippines and Vietnam by 6-7%. Poorer countries in

the region, such as Myanmar and Cambodia, are growing even faster. For

investors hedging against China, South-East Asia has become the manufacturing

hub of choice. Its consumers are now rich enough to comprise an alluring

market. In commercial as well as geopolitical terms, South-East Asia is a

prize.

Of the two

competitors, China looks the more likely prize-winner. It is the region’s

biggest trading partner and pumps in more investment than America does. At

least one South-East Asian country, Cambodia, is in effect already a Chinese

client state. And none is willing to cross China by openly siding with America

in the superpowers’ many rows.

However, as close as

South-East Asia’s ties with China appear, they are also fraught (see article).

Chinese investment, although prodigious, has its drawbacks. Chinese firms are

often accused of corruption or environmental depredation. Many prefer to employ

imported Chinese workers rather than locals, reducing the benefits to the

economy. Then there is the insecurity bred by China’s alarming habit of using

curbs on trade and investment to punish countries that displease it.

China also dismays

its neighbors by throwing its weight around militarily. Its seizure and

fortification of shoals and reefs in the South China Sea, and its harassment of

South-East Asian vessels trying to fish or drill for oil in nearby waters, is a

source of tension with almost all the countries of the region, from Vietnam to

Indonesia. China also maintains ties with insurgents fighting against the

democratic government of Myanmar and has in the past backed guerrillas all over

the region.

This sort of

belligerence makes China unpopular in much of South-East Asia, building, alas,

on dismaying traditions of prejudice. Anti-Chinese riots often erupt in

Vietnam. Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, has seen protests

about everything from illegal Chinese immigration to China’s treatment of its

Muslim minority. Even in tiny Laos, a communist dictatorship where public

dissent is almost unheard of, whispered gripes about Chinese domination are

commonplace. South-East Asian leaders may not dare criticize China openly for

fear of the economic consequences. Still, they are also wary of being too

accommodating for fear of their own citizens.

China’s bid for

hegemony in South-East Asia is thus far from assured. South-East Asian

governments have no wish to renounce trade with and investment from their

prosperous neighbor. But they also want what America wants: peace and stability

and a rules-based order in which China does not get its way by dint of sheer

heft. Like all middling powers, the big countries of South-East Asia have an

incentive to hedge their bets and see what favors they can extract from the

Goliaths of the day.

To help South-East

Asia avoid slipping into China’s orbit, America

could encourage it to keep its options open and build counterweights to

Chinese influence. One mechanism is more regional integration. Trade and

investment among the countries of South-East Asia outweigh the business they do

with China. Another mechanism is strengthening ties with other Asian countries

such as Japan and South Korea, one ASEAN has rightly embraced. Above all,

America should not fall into the trap of trying to force its members to pick

sides. That is the one thing South-East Asia is determined to resist.

For updates click homepage here