By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

The Consequences Of China's Peace

Deal

Yesterday when

Ukraine downs the Russian barrage, China is now sending

a special envoy to Ukraine to help reach a political settlement that many

say would benefit Russia. The intercept of Russian intelligence

shows Beijing wanted to disguise lethal aid. But China will

proceed cautiously.

On April 21, China’s

ambassador to France, Lu Shaye, proclaimed that whether Crimea is part of

Ukraine “depends on how the problem is perceived.” He added more fuel to the

fire by saying that “ex-Soviet countries don’t have an effective status in

international law”—questioning the sovereignty of Ukraine and that of over a

dozen countries that were part of the Soviet Union. These inflammatory remarks

provoked widespread condemnation, with 80 European lawmakers urging the French

government to expel Lu. Beijing tried to downplay the situation, stating that

Lu only expressed his personal views.

Five days after Lu

made his remarks, Chinese President Xi Jinping went forward with a

long-promised phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Although

some observers welcomed this call to contain the damage from Lu’s comments,

others suspected the ambassador’s remarks had been designed to probe how Europe

would react if China officially embraced his position. Following Xi’s call,

Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang visited Germany, France, and Norway in early

May. And this week, Li Hui, China’s new special representative to deal with the

Ukraine conflict, will visit Ukraine, Poland, France, Germany, and Russia to

discuss achieving “a political settlement to the Ukraine crisis.”

These events have

spotlighted Beijing’s struggles to balance its conflicting objectives in

Ukraine. China aims to prioritize its relations with Russia, its most

vital strategic partner, which has biased its position on the conflict in favor

of its neighbor. At the same time, Beijing wishes to ensure that Europe does

not join an anti-China bloc—an increasingly important goal given Chinese

policymakers’ growing pessimism that they can prevent the deterioration of

U.S.-Chinese relations. These concerns have led China to try to cast itself as

neutral and limit some of its support for Russia. However, as the war drags on,

Beijing finds this position increasingly difficult to sustain. The conflict is

weakening its closest strategic partner while complicating China’s security

environment.

As a result, Beijing

has gotten off the sidelines and has begun to offer its good offices to

bring both sides to the negotiating table. It has articulated a vision for

global security, issued a position paper on Ukraine, and appointed a special

representative to engage all parties involved in the conflict. It

also explores ways to recast the Ukraine conflict as one driven by a

long and complex history to undercut external aid to Ukraine and defend Russian

interests. In taking this more active role, however, China’s efforts will

likely be high-profile but slow in delivering results. China is likely to do

just enough to cast itself as a helpful and responsible global leader but not

enough to be held accountable for ending the Ukraine conflict on terms that

would be fair and acceptable to both sides.

Getting It Wrong

Shortly after Russia

invaded Ukraine last year, leading Chinese experts provided a range of

assessments about the war’s impact and trajectory. Many initially assessed that

the conflict would be brief, and some even predicted it would have

no geopolitical implications beyond Europe.

Lethal methods of

warfare were gathered informally in Beijing to analyze the impact of the

Ukraine conflict on the global order. They assessed that the match was unlikely

to end soon and that China could benefit from a prolonged fight. They argued that

China should maintain its neutrality to turn the crisis into an opportunity to

recast its relationships with Russia, the United States, and Europe, all of

which would suffer mounting costs as the war dragged on.

The Chinese

strategists advocated for personal assistance to Russia to ensure it could

sustain the fight and would not collapse. However, they counseled against

drifting entirely into Moscow’s camp. These experts believed the conflict could

allow Beijing to partially smooth ties with the United States, mainly since

there was a greater chance of working with U.S. President Joe Biden’s

administration than with a potential future Trump administration.

They also recommended

that Beijing play an active diplomatic role in the conflict’s aftermath. China

should advocate positions that most countries support—such as respecting

sovereignty and abandoning a Cold War mentality—to position itself to

shape the international response in beneficial ways. They also pressed China to

take on new responsibilities, including acting as an arbitrator and rules-maker

for this emerging global order.

Although it is not

clear if China’s leadership fully agreed with these experts’ positions, many of

their suggestions have been embraced by Beijing. China has tried, for example,

to position itself as neutral in the Ukraine conflict. The government’s

position paper on Ukraine, published in February, also included these Chinese

experts’ specific points about respecting countries’ sovereignty and abandoning

a Cold War mentality.

However, the

strategists’ cautious optimism about Beijing’s ability to exploit the

conflict's advantage soon collided with reality. Despite China’s efforts, most

developed countries viewed its position on Ukraine as deeply pro-Russia. Many

Chinese analysts worried that this perception could poison China’s reputation

in Europe, causing governments and the public to see China as an enemy.

Similarly, U.S.-Chinese relations have worsened even as the Ukraine conflict

has dragged on. China’s response to the war in Ukraine also heightened global

concern about Beijing’s possible intentions to use force against Taiwan,

thereby strengthening international support for Taipei—and aggravating China’s

security environment.

By the middle of 2022,

Chinese experts saw the prolonged conflict in Ukraine as harmful to Chinese

interests. The dominant perspective within the country was that the fighting

represented a NATO-backed proxy war to weaken Russia, China’s friend, in

countering Western suppression and encirclement. Many argued that the United

States was the conflict’s primary beneficiary: it was learning valuable lessons

in propping up Ukraine’s fight, including leveraging coercive sanctions against

Russia. It could use these same tactics against China in the future. At the

same time, the war had allowed Washington to strengthen and revitalize its

alliances in Europe and beyond. It was clear that the Ukraine conflict had

weakened Russia, Chinese experts believed, but it was less sure that the United

States or Europe had suffered equally.

Beijing’s concerns

over the Ukraine conflict intensified over the past year. Russia faced strong

Ukrainian military resistance and ran low on weapons and munitions. Chinese

experts were also concerned about possible direct U.S.-Russian confrontation

and nuclear escalation. These two scenarios could make it impossible for China

to stay on the sidelines. Chinese analysts judge that Russia could use nuclear

weapons as a last resort if it felt at risk of losing the war. Chinese media

reported Russia’s repeated atomic threats and its October 2022 drills

involving its strategic nuclear forces. From Beijing’s perspective, however,

the danger of atomic use does not come only from Russia. China believes that NATO

has also engaged in nuclear saber-rattling, including through a nuclear

deterrence exercise that co-occurred with Russia’s nuclear drills.

By the middle of

2022, Chinese experts saw the prolonged conflict in Ukraine as harmful to

Chinese interests. The dominant perspective within the country was that the

fighting represented a NATO-backed proxy war to weaken Russia, China’s friend,

in countering Western suppression and encirclement. Many argued that the United

States was the conflict’s primary beneficiary: it was learning valuable lessons

in propping up Ukraine’s fight, including leveraging coercive sanctions against

Russia. It could use these same tactics against China in the future. At the

same time, the war had allowed Washington to strengthen and revitalize its

alliances in Europe and beyond. It was clear that the Ukraine conflict had

weakened Russia, Chinese experts believed, but it was less sure that the United

States or Europe had suffered equally.

Beijing’s concerns

over the Ukraine conflict intensified over the past year. Russia was facing

strong Ukrainian military resistance and running low on weapons and munitions,

and Chinese experts were also concerned about the possibility of direct

U.S.-Russian confrontation and nuclear escalation. These two scenarios could

make it impossible for China to stay on the sidelines. Chinese analysts judge

that Russia could use nuclear weapons as a last resort if it felt at risk of

losing the war. Chinese media reported Russia’s repeated atomic

threats and its October 2022 drills involving its strategic nuclear

forces. From Beijing’s perspective, however, the danger of atomic use does not

come only from Russia. China believes that NATO has also engaged in nuclear

saber-rattling, including through a nuclear deterrence exercise that

co-occurred with Russia’s nuclear drills.

These concerns are

evident in Xi’s escalating rhetoric about the Ukraine war. When hosting German

Chancellor Olaf Scholz in Beijing in November, Xi stated that the international

community should “oppose the use of or the threat to use nuclear weapons,

advocate that nuclear weapons cannot be used and that nuclear wars must not be

fought, and prevent a nuclear crisis in Eurasia.” Later that month, in a

discussion with Biden in Bali about the Ukrainian crisis, he said that

“conflicts and wars produce no winner” and “confrontation between major

countries must be avoided.”

Chinese fears about

Ukraine are reflected in the stories covered by the country’s media. In

December, Chinese newspapers shared Russian expert assessments that

the Ukraine conflict risked leading to a direct military confrontation between

the United States and Russia in 2023. Chinese media also saw the mid-March

incident in which a Russian warplane downed a U.S. surveillance drone to

validate these concerns and reprinted Western analyses that the episode marked

the first direct physical contact between the U.S. and Russian militaries.

At the same time,

Beijing detected cracks in Western support for Ukraine. A report published in

late February by the China Institutes of Contemporary International

Relations, a leading research institution housed under China’s Ministry of

State Security, assessed that Western leaders “may object to long-term aid to

Ukraine and grow tired of it.” It noted that leaders in Germany, France,

and the United Kingdom had begun pressuring Zelensky to negotiate with Russia,

and there were also voices in the United States calling for an end of aid to

Ukraine and the need to reach a peace settlement. Echoing this line of thinking

in his April call with Zelensky, Xi noted that “rational thinking and

voices [are] now on the rise” about the conflict and that it is, therefore,

necessary “to seize the opportunity and build up favorable conditions” for a

settlement.

These developments and

continuous international pressure on China not to provide lethal aid to Russia

led Chinese Politburo member Wang Yi to warn at the Munich Security Conference

in February that the conflict could be “escalated and protracted.” He repeated

Xi’s line that there are no winners in wars and added that the Ukraine conflict

“should not go on anymore.” Shortly afterward, Chinese Foreign Minister Qin

Gang said that China was deeply worried that the conflict could “spiral out of

control”—the first time Beijing had used that phrase.

Course Correction

These shifting assessments

have caused Beijing to alter its approach toward the conflict in Ukraine.

Whereas it previously stayed on the sidelines, China has cautiously stepped

into the arena in recent months. In particular, the Chinese government has

aimed to portray itself as a key actor that can solve international conflicts.

On February 21, it released its Global Security.

Initiative

Concept Paper outlined Xi’s vision for solving the world's security challenges. The

paper promised to “eliminate the root causes of international conflicts” and

“improve global security governance.” It also criticized Washington’s extensive

global influence, vowing to change the fact that regional and global tensions

have “occur[red] frequently” under U.S. leadership.

Three days later, China

released a position paper on Ukraine outlining a dozen broad principles for a

political settlement to the conflict. The report echoed Moscow’s talking

points, even declining to mention that Russia had invaded Ukraine and violated

its sovereignty. But it did include issues—such as the need to respect

authority and territorial integrity—that appeared to account for Ukraine’s

interests.

During this period,

China scored a diplomatic victory in another part of the world. On March 10,

Saudi Arabia and Iran announced an agreement to restore full diplomatic

relations. This breakthrough, they claimed, was achieved due to “the noble

initiative” of Xi and represented the first success of the Global Security

Initiative. In reality, China did not initiate this effort—the United States

encouraged Saudi Arabia and Iran to begin discussions in 2021. At most, China

provided a hospitable venue for the two countries to hash out their differences

and represented a neutral party that could convince each side to operate in good

faith. But it is possible that this accomplishment made Xi overconfident about

what he could achieve on other diplomatic fronts.

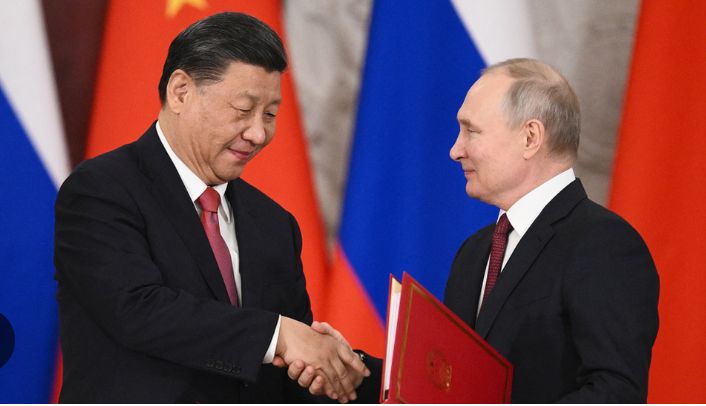

Against this

backdrop, Xi intensified his efforts in Ukraine. In early March, he hosted

Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko, a close ally of the Kremlin, and

then traveled to Moscow to meet Putin himself. In late March and April, Xi met

in person with several world leaders to discuss Ukraine—seeking to engage not

only with European voices but also to elevate the views of key developing

countries. This included Brazilian President Luiz Inácio

Lula da Silva, who called for a “G-20 of peace” composed of neutral countries

to play a leading diplomatic role. Then in late April, Xi

called Zelensky at Ukraine’s request and designated a special

representative to engage with all parties on how to reach a political solution

to the conflict.

Overall, China likely

views its diplomatic efforts as affording it a more significant role in

determining the course of the war, which it views as being manipulated and

prolonged by the United States. Diplomacy could allow Beijing to

deflect criticism, set a new narrative about the conflict, and shape the

outcome in ways that would benefit it. China could also use its ability to

negotiate with all parties as a bargaining chip to pressure other countries to

respect its interests. It’s possible that French President Emmanuel Macron’s

public declaration in April that it is not in France’s interest to support the

U.S. agenda to defend Taiwan was partially motivated by Paris’s desire for

China to play a constructive role in Ukraine.

False Hope?

The degree to which

China can leverage its diplomatic efforts to its advantage depends on how the

country seeks to proceed. Beijing has yet to offer specific proposals on

resolving the Ukraine conflict. And suppose its approach during the six-party

talks on North Korea or its mediation between Saudi Arabia and Iran guides its

efforts in Ukraine. Nobody should expect China to put forward creative

diplomatic proposals in that case. While Beijing may be able to get both sides

to the negotiating table, it has a long way to go if it wants to convince the

international community that it is truly an honest broker.

Although Beijing emphasizes

its seemly neutral push for finding a path toward peace through direct

dialogue, its portrayal of the United States and NATO as fueling the

conflict by providing arms to Ukraine is a crucial aspect of its messaging.

This narrative aims to rally the global South and undercut U.S. and European

arguments that the international community should support Ukraine against the

Russian invasion.

The reality is that Ukraine

cannot sustain the fight if its external political, economic, and military

support dries up. The United States and Europe have already asked countries on

the sidelines to help replenish Ukraine’s weapons stockpiles. China’s push for

dialogue could disproportionately impact Kyiv if countries become wary of doing

so. At the same time, China’s call for an immediate cease-fire could allow

Russia to consolidate its gains at a time when it still controls

significant portions of Ukrainian territory.

China’s evolving

foreign policy discourse is also not favorable to Ukraine. Chinese experts are

working to resolve the contradiction between Beijing’s emphasis on respect for

sovereignty and its refusal to describe the conflict as a Russian invasion of

Ukraine. Some Chinese scholars have suggested that sovereignty and territorial

integrity should be viewed as only one of 12 core principles for China to

balance—in other words, not the most important one or a value that needs to be

respected completely.

But suppose China

wanted to maintain its position that the principle of sovereignty and

territorial integrity is non-negotiable. In that case, Lu Shaye’s questioning

of the sovereignty of post-Soviet states might be the solution. It is telling

that despite the international condemnation of Lu’s remarks, Beijing has yet to

publicly reprimand him beyond disavowing his comments. Last week, China’s

Foreign Ministry even came to his defense by denying the “false information”

that Lu was recalled to China.

Lu’s comments align

with two Chinese talking points: that Russia had “legitimate security concerns”

to use force against Ukraine and that the Ukraine crisis was caused by

“profound historical backgrounds and complex, realistic reasons.” In other

words, Beijing could argue that Russia’s 2022 invasion did not start the

conflict in Ukraine. If that is the case, Russia is not the only aggressor, and

resolving the conflict requires going back in history to a time when Ukraine

(and Crimea) was part of the Soviet Union. This could make it easier to

push for a political settlement where Russia retains control of the parts of

Ukraine it has conquered.

China does not need

to argue that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was morally right— and such

arguments are likely to be rejected by the West. China needs to obscure the

causes of the war to cast doubt on the moral high ground of the United States

and Europe. Beijing may be banking on growing Western division and fatigue as

the conflict drags on, which could allow countries from the global South to

increase pressure on the West to end the war. As Russian and Ukrainian

capabilities are further exhausted, both sides could find themselves looking

for a way out of the war.

A Questionable Peacemaker

The international

community should not place too much hope on China’s mediation efforts nor alter

any existing efforts to deter Russian aggression or to create conditions for

ending the conflict. China’s actions are likely high in profile but slow and

questionable in substance.

Beijing knows it will

be tough to reach any political settlement and does not want to be blamed for

unsuccessful efforts. At the same time, it wants credit for any progress that

could be made. These dueling tendencies are evident in Xi’s statement that

China “did not create the Ukraine crisis, nor is it a party to the crisis” and

his claim that Beijing cannot “sit idly by” as the conflict escalates.

Beijing has also not

shown any willingness to impose costs on Moscow if the Kremlin refuses to

follow its diplomatic lead. This March, Xi, and Putin issued a joint statement

that rejected the deployment of nuclear weapons abroad. But when

Putin declared that he would place nuclear weapons in Belarus days later, China

largely avoided criticizing him.

China will proceed

cautiously. It will be wary of offering anything more than bringing Ukraine and

Russia to the negotiation table. Indeed, Beijing will most likely focus on

balancing its competing priorities—on the one hand, maintaining its

relationship with Moscow and not entirely alienating European countries—by

doing just enough to deflect criticism of its role. China wants to show that it

is helpful but does not want to risk being accused of pushing one side’s

interests over another’s in the diplomatic process.

Suppose Beijing does

eventually offer any concrete proposals to settle the war. In that case, there

is a risk that even seemingly neutral recommendations, such as freezing the

fighting in place, could prioritize the interests of Russia. Beijing is

signaling that it wants to play a more active diplomatic role, but the reality

is that it is operating in an arena where it has little experience.

For updates click hompage here