By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The future war between China and the US

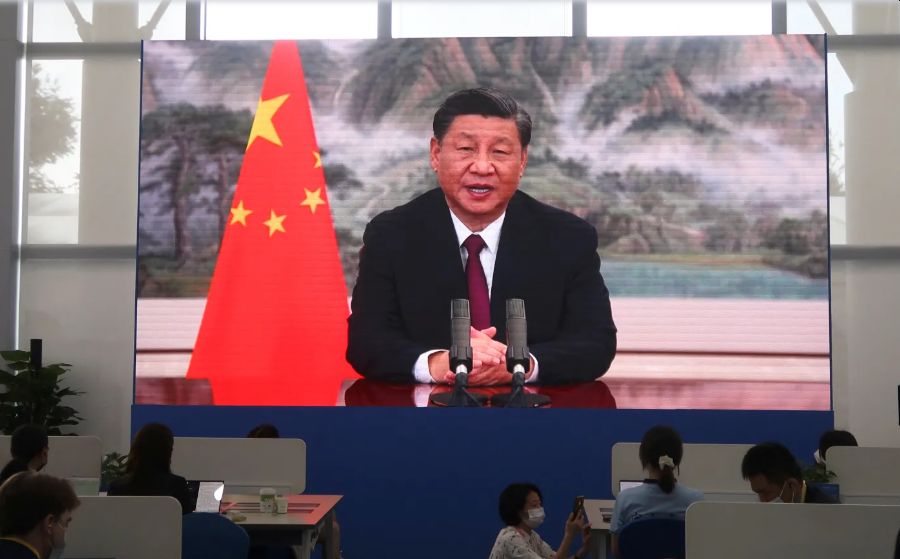

Chinese President Xi

Jinping has made it abundantly clear that “reunifying” Taiwan with mainland

China is a legacy issue, something he intends to accomplish on his watch

through political and economic means or, if necessary, military

force. Right now, he is preoccupied with the COVID-19 crisis, the slowing growth of the

Chinese economy, and the upcoming 20th Party Congress, where he hopes to secure

a third term as chair of the Chinese Communist Party. But once these immediate

concerns are addressed, it is possible that sometime in the next five years, Xi

will consider taking Taiwan by force, either because nonmilitary efforts at

reunification have fallen short or because he believes his chances of success

will diminish if he waits and U.S. military capabilities grow.

Where China has no rights over Taiwan, the U.S. policy of “strategic

ambiguity” deliberately leaves uncertain whether and under what circumstances

the United States would defend Taiwan against a Chinese invasion. But it is

clearly in the United States’ interest to deter China from attempting such

an operation in the first place. A Chinese assault on Taiwan that draws a

U.S. military response will likely ignite a protracted conflict that escalates

beyond Taiwan. Like great powers that have gone to war in the past, the United

States and China would grow more committed to winning as a conflict progressed,

making the case to the public that it has too much to lose to stop fighting.

Given that both China and the United States have substantial nuclear arsenals,

preemptively deterring a conflict must be the game's name. To do so, the United

States must help Taiwan modernize and enhance its self-defense capabilities

while strengthening its ability to deter China from using force against the

island. What among others now is ending the post-Cold

War era.

The good news is that

the Biden administration’s new National Defense Strategy, transmitted to

Congress in March and due to be released in unclassified form in the coming

months, reflects the need to move with incredible speed and agility to

strengthen deterrence in both the near and long term. The strategy

reinforces the focus on a more aggressive China as the United States’

primary threat. It emphasizes a new framework of “integrated

deterrence,” drawing on all instruments of national power and the

contributions of U.S. allies and partners to deter future conflicts that are

likely to be fought across multiple regions and domains. It also

identifies several technologies that will be critical for maintaining the U.S.

military’s edge—including artificial intelligence, autonomy, space

capabilities, and hypersonics—and calls for more

experimentation to prepare for future warfighting. And it rightly aspires

to bolster the United States military position in the Indo-Pacific and substantially deepen its

relationships with important allies and partners.

As we have seen, the

world is witnessing the revival of some of the worst aspects of traditional

geopolitics; great-power competition, imperial ambitions, and fights over

resources. Hence the Pentagon is now developing offensive and defensive

capabilities that will take decades to design, build, and deploy. But emerging

dual-use technologies are changing the character of warfare much faster than

that. This is already evident in Ukraine,

where commercial satellite imagery, autonomous drones, cellular communications, and social media have

shaped battlefield outcomes. For example, satellite imagery created with

synthetic aperture radar, which can see through clouds and at night, has

provided a nearly real-time view of Russian movements, enabling Ukraine and NATO

countries to counter Kremlin misinformation and sometimes giving Ukrainian

forces a tactical advantage. Using this satellite imagery, drones

have collected valuable intelligence and serve as effective antitank

weapons. Geolocation data has enabled the Ukrainian military to target Russian

generals who carelessly used their cell phones. Cell phones have also enabled

Ukrainians to document atrocities, while social media has bolstered the

Ukrainian resistance and international support for its cause. Many technologies

previously available only to

governments are now readily available to individuals,

including in countries hostile to the United States. To harness the power of

these new technologies, the U.S. military must adopt new capabilities much

more swiftly than it has in the past.

China—which leads the

world in manufacturing small drones and advanced

telecommunications—already exhibits this sense of urgency. It compels

private companies to work closely with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to

accelerate the development and adoption of new concepts. China has carefully

studied U.S. capabilities for decades, even stealing the designs for many major

U.S. weapons systems. Now, it is rapidly modernizing the PLA, exploiting

asymmetries between U.S. capabilities and its own to diminish Washington’s

military advantage. It also makes use of innovations from its commercial

sector. For example, the PLA uses commercially derived artificial intelligence

technologies to power drone swarms and autonomous underwater vehicles. It also

draws on leading private companies for electronic warfare tools, virtual

reality technologies for training, and sophisticated intelligence,

surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. Yet the bottom line is that

the U.S. military is simply not moving fast enough to ensure that it can

deter China in the near term. Suppose Washington wants to deny

Beijing the ability to blockade or overrun Taiwan in the next five years. In that case, it must step

up the pace and scale of change and adopt a new approach: relentless leadership

and focus at the top of the Department of Defense to make deterring China a

daily priority, immediate investments in rapidly fielding promising prototypes

at scale, greater integration of commercial dual-use technologies, and an

emergency effort to solve the most critical operational problems the

United States would face in deterring and defeating a Chinese assault on

Taiwan. Such a crash effort is not without precedent. Consider the Pentagon’s

urgent endeavors to increase unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and

reconnaissance capabilities to counter-terrorism after 9/11 and the

rapid fielding of mine-resistant vehicles to protect U.S. troops from

improvised explosive devices during the war in Iraq.

Planning for a

blockade or invasion of Taiwan has long been the highest priority for

the PLA, from its acquisition priorities to its exercises to its military

posture. This possibility has motivated decades of Chinese investment in

“anti-access/area-denial” capabilities designed to prevent U.S. forces from

projecting power into the region to defend Taiwan. Many of the

PLA’s new capabilities are now online at scale, significantly

complicating the U.S. military’s operational challenges. Yet many of the

U.S. military’s most promising capabilities to counter China in the event of a

conflict over Taiwan will not be ready and fully integrated into the force

until the 2030s. This creates a window of vulnerability for Taiwan, most

likely between 2024 and 2027. Xi may conclude

he has the best chance of military success should his preferred methods of

political coercion and economic envelopment of Taiwan fail. Indeed, thanks

to the PLA’s substantial investments, the U.S. military has reportedly failed

to stop a Chinese invasion of Taiwan in many war games carried out by

the Pentagon.

Need for speed

To deter Chinese

aggression against Taiwan in the next two to five years, the United

States must immediately reorient U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific.

Acquisition processes

that worked well for the United States during the Cold War are ponderous and

leave the Pentagon ill-equipped to compete in a period of profound

technological disruption against a faster-moving, more capable adversary than

the Soviet Union. the executive branch and private sector appear

united in the view of what needs to be done to provide the

best deterrence against China and, if necessary, the best defense of

Taiwan.

First, the Pentagon’s

leadership must urgently address the gap between what the United States has and

what it needs to deter China soon. With the commanders of the military’s

geographic and functional combatant commands focused on current operations

and the chiefs of the military services focused on building the capabilities

they will need in the 2030s and beyond, the Department of Defense has no

accountable senior leader solely focused on improving the United States’

ability to deter Chinese aggression in the 2024–27 timeframe.

Job number one would

be to lead an intensive, department-wide sprint to identify the most

significant problems associated with deterring an attack on Taiwan; determine

which currently unfunded priorities should receive more resources (such as

addressing critical munitions shortages); canvass the different branches

of the military, the units of the Pentagon dedicated to innovation, and defense

and commercial firms for solutions; and then work with leaders in Congress

to reallocate funds to ensure these capabilities are fielded within the next

two to five years. Success would be measured by the new

capabilities deployed into the hands of U.S. warfighters and the speed at which

this is done—not by the number of experiments and demonstrations performed.

One initial area of

focus could be rapidly fielding large numbers of smaller autonomous systems to

augment conventional capabilities at low cost. For example, small autonomous

intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems could be deployed to

create a vast and much more resilient sensor network that improves U.S.

situational awareness across the Indo-Pacific. Similarly, swarms of tiny, AI-enabled expendable strike systems could be

brought online, enabling U.S. forces to confound and overwhelm an adversary in

any number of situations. Such off-the-shelf systems can be fielded quickly and

cheaply with easy-to-upgrade software.

The United

States could also improve its ability to hold Chinese naval forces at risk

and thereby deter them from crossing the Taiwan

Strait by arming U.S. bombers deployed to the Indo-Pacific with large

numbers of long-range anti-ship missiles, as the Pentagon’s Strategic

Capabilities Office has demonstrated. Urgently funding the scaling and

deployment of such innovations should be among the Department of Defense’s

highest priorities in the next two to five years. Yet, few have been fully

funded in the most recent budget request. Ideally, some of these efforts could

be undertaken jointly with the capable militaries of U.S. allies.

One could also

accelerate and scale up its security assistance to Taiwan, making the island

more of an indigestible “porcupine” and improving its ability to slow down and

impose costs on any aggressor. In particular, the United States should assist

Taiwan with operational planning, war-gaming, and training while also helping

Taiwan leverage commercial capabilities to improve its situational

awareness and acquire critical asymmetric capabilities such as air and

missile defenses, sea mines, armed drones, and anti-ship

missiles. U.S. National Security Adviser Jake

Sullivan indicated at the Aspen Security Forum in July that planning for

such an effort is already underway. Still, hardening Taiwan’s defenses in the

two- to five-year time frame will require more hands-on, determined leadership

to overcome persistent bureaucratic obstacles and delays. The Biden

administration’s recent announcement that it will sell both Harpoon and

Sidewinder missiles to Taiwan is a promising first step.

To augment

current U.S. capabilities, the Department of Defense should adopt a

“fast-follower” strategy to accelerate the adoption of commercial technologies

that solve critical operational problems. Private companies are leading the

development of cutting-edge technologies such as AI and autonomous systems, so

the Pentagon must be fast to follow these commercial innovators and make

itself a more attractive customer by streamlining the acquisition process for

commercial technologies. Deterring a Chinese assault on Taiwan, or

defending against one, will require rapidly fielding a range of

new capabilities from commercial dual-use suppliers. Commercial

technologies such as advanced secure communications, AI software, small drones,

and synthetic aperture radar satellite imagery can deliver novel capabilities

at a fraction of the cost of technologies developed to meet military

requirements and specifications—and in one to two years or one to two

decades. Accelerating the early adoption of commercial technologies

such as these will help the Pentagon erode Beijing’s confidence in its ability

to take Taiwan by force.

Following fast

Instituting

a fast-follower strategy would require overhauling the Pentagon’s

outdated, cumbersome, and painfully slow procurement processes to deal more

efficiently with commercial technology vendors. Currently, the department

spends years developing detailed specifications for nearly every capability

that it procures—whether or not that capability is already available off the

shelf. And if a system does not meet a specified military requirement, finding

funding to buy it from a commercial vendor can be tricky, even if it meets a

priority operational need. Given the urgency and gravity of the challenge posed

by China, the Pentagon must innovate to speed up the procurement process for

commercial technologies dramatically.

To that end, the

Pentagon should designate units that can assess, budget for, and procure

specific commercial capabilities such as small drones and counter-drone

capabilities that are not designed with a specific military branch. Doing so

will require training a new cadre of acquisition professionals specializing in

the rapid procurement and integration of commercial technologies. It will also

require keeping pace with private-sector innovation so that U.S. warfighters

can be outfitted with the latest technology.

These Pentagon

procurement units should follow commercial best practices, maximizing

competition among vendors while minimizing the costs for vendors to

participate. The Defense Innovation Unit, which works to accelerate retail

technology adoption, already exclusively uses these practices,

drawing an average of 43 vendors to each of its 26 competitive

solicitations last year. Using a special authorization from Congress known

as Other Transaction Authority, the Department of Defense can also eliminate

requirements for vendors to recompete for contracts once they have successfully

competed with a prototype; these vendors could proceed immediately to follow-on

production contracts to scale the new capability.

Finally, the Pentagon

should deepen its collaboration with U.S. allies in procuring critical

capabilities, commercial sourcing technology from these countries, and selling

proved technologies to their militaries. Prevailing in its competition

with China will require the United States to innovate beyond its borders

and collaborate with allies to field joint capabilities. The

fastest way to do this is with commercial technologies that are unclassified

and, therefore, easily shareable, as the war in Ukraine has demonstrated. And

again, here, the German Chancellor demonstrated the seriousness of the

situation, who, afther a recent telephone

conversation with this case, reported that there is no indication that

Putin has changed his stance. As the UN chief added, prospects for peace

are ‘minimal.’

Now or never?

Many analysts will

say that the Department of Defense is already modernizing the U.S. force and

investing in technology and innovation to compete with China. And the Pentagon

is indeed moving in the right direction. But it must make more significant

changes—and faster. Most of the department’s investments in research and

development will not yield fielded capabilities in the two- to a five-year

period that is critical for deterring China.

To effectively

prepare for the approaching window of vulnerability in which Xi may

conclude he has the best chance of taking Taiwan by force, the Pentagon must do

a better job of balancing its need to invest in long-term capabilities with

what it needs today. In so doing, it can create an element of strategic

surprise, a stronger deterrent, and a more modern force that combines

traditional large weapons platforms with new and transformative capabilities.

If the Pentagon fails to adopt a new vision of warfighting and the PLA

succeeds, the United States will find itself with plans and platforms to fight

the last war instead of the one it may face next.

Xi has likely learned

a dangerous lesson from Russia’s mistakes in Ukraine—namely, that if

he wants to take Taiwan by force, he needs to go big and move fast. A potential

conflict over the island could unfold much more rapidly than the war

in Ukraine, with China attempting to create a fait accompli within

days. Therefore, the United States needs to dramatically strengthen deterrence

and undermine Beijing’s confidence in its ability to succeed.

The U.S. Congress has

already recognized the need to rapidly improve deterrence by funding the

Pacific Deterrence Initiative, which aims to provide the U.S. Indo-Pacific

Command with the necessary capabilities. The head of that command, Admiral John

Aquilino, has repeatedly stated that he is most interested in additional

capabilities that can be fielded in the next few years—not those that can be

delivered decades from now.

The stakes could not

be higher, and the clock is ticking. The United States is running out of

time to deploy the new capabilities and operational concepts it

needs to deter China soon. The Department of Defense still has time to make the

necessary changes—but only if it acts with greater urgency and focuses

now.

For updates click hompage here