By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

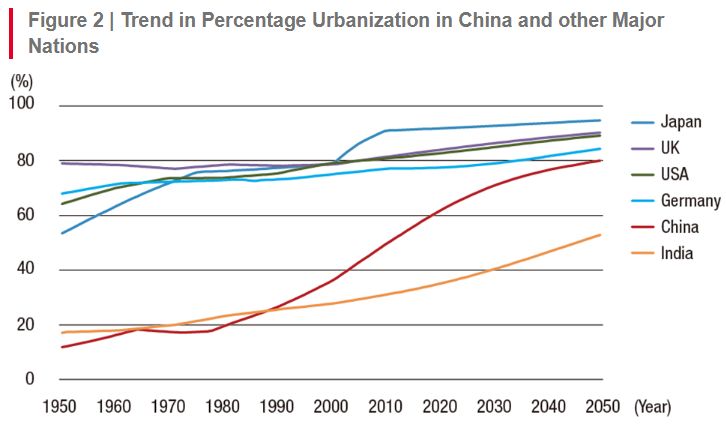

The New City Planning

The future cities are

here—or, at least, in the works. From Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s

dreams of Neom, a $500 billion planned city, to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s

ambitions for the city of Xiongan, which he calls his

“personal initiative,” so-called smart cities are being built from the ground

up, to considerable global skepticism.

In this edition of

Flash Points, we explore how cities, new and old, provide glimpses into global

leaders’ ambitions and how they’re changing as the surveillance state expands,

urban populations grow, and local governments become increasingly important to

state-level diplomacy.

China’s City Planning in Xiong

About 60 miles south

of the center of Beijing, a new city is being built to showcase high-tech,

ecologically friendly development. Its massive high-speed

rail station and

“city brain” data center have been heralded by Chinese state

media as evidence of the speed and superiority of China’s growth model—not

least because the city is a “signature initiative” of Chinese President Xi Jinping. Xiongan

New Area is also a test for whether China can boost domestic innovation and

climb into the ranks of advanced nations in the face of slowing economic growth

and efforts by the United States and others to restrict its access to advanced

technology.

Xiongan offers a window into what Xi’s vision of state-led

innovation looks like on the ground. Xi has called the city his “personal

initiative” and a qiannian daji, or “thousand-year plan of national significance.”

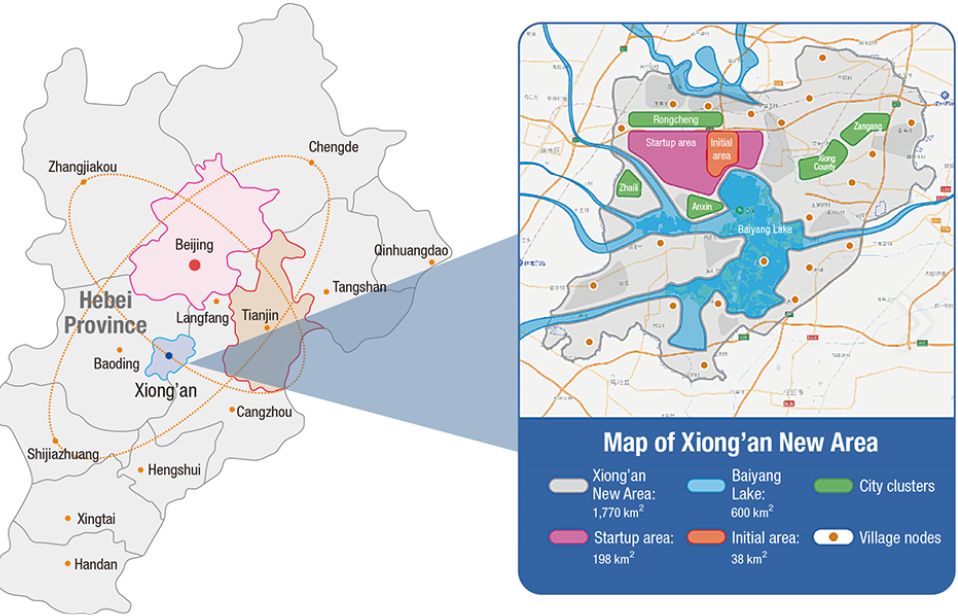

The plan for Xiongan, formally unveiled in 2017 to

relieve pressure on Beijing and promote the “coordinated regional development”

of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, has faced financial

struggles due to the huge

investment costs—even more of a problem given China’s mounting real estate

crisis. Overall, the new area encompasses about 650 square miles, with a

planned population of around 3 million; currently, the three counties comprising the zone

have around 1.4 million long-term residents. As of September 2022, 400 billion

yuan (about $57 billion) in completed investment had been reported in the city overall.

While Xi has stacked

the new Politburo Standing Committee with officials loyal to him, he has

also elevated those with strong science and engineering backgrounds.

In his speech at the 20th Party Congress last October, Xi

declared that “innovation will remain at the heart of China’s modernization

drive” and that China has “worked hard to promote high-quality development and

pushed to foster a new pattern of development.” Nevertheless, a confluence of

factors, including COVID-19 lockdowns and trade tensions, contributes to slower growth in China.

Rather, Xi’s vision

of innovation is one in which the state and party play a leading role. Xi has

led a crackdown on private technology firms such as Alibaba but has also

promoted policies, such as his Made in China

2025, that aim to boost

research-and-development spending and subsidies to give Chinese firms

competitive advantages in industries including biotechnology, robotics,

artificial intelligence, and semiconductors. Xi’s policies favor “hard tech” over software-based platform app companies. The

first party secretary of Xiongan was Chen Gang, who oversaw Beijing’s Zhongguancun

high-tech park before being transferred to Guizhou, where under Xi ally Chen

Miner, he helped turn the southwestern province into a center of big data and

cloud computing.

The approach to

innovation in Xiongan involves embedding technology

within the fabric of the city and innovation processes within the party state. Xiongan Group was created as the investment vehicle for the

area’s overall development, under the control of Hebei province but backed

partially by loans from China Development Bank. China Satellite Communications

Co., the energy giant China Huaneng Group, and Sinochem Holdings were the first central state-owned

enterprises to begin the construction of offices in the new area. Others now

include the big three telecoms, China State Grid, and China Mineral

Resources Group, a

conglomerate set up last year to centralize China’s coal mining industry. These

state-owned enterprises could use Xiongan as a test

bed for new technologies. Research institutes and satellite branches of several Beijing universities are planning to open in the area around 2025.

The relocation of these major units and their thousands of employees will

determine how quickly Xiongan’s development proceeds.

Even as China’s

economy has slowed during COVID-19 lockdowns and the global downturn,

construction of the first phase of Xiongan has

marched on: A huge high-speed rail station to connect the city with Beijing

opened in 2020, followed by residential slabs, massive underground utility

corridors, and the city brain data center, which will serve as the nerve

center of the city’s digital systems. The first section, Rongdong,

has been mostly completed, housing 170,000 people. Media reports of new schools opening show the effort to build high-quality

public amenities to attract residents to the city: Branches of Beijing

institutions such as Shijia Primary School and

Tsinghua University High School are among the new educational institutions

being built in Xiongan.

The goal of Xiongan is to deploy novel city-scale technological systems

within the urban fabric: underground logistics systems, water treatment

facilities, and infrastructure for data collection and management. Xiongan has been described as “three cities”: the city aboveground, the city underground, and the

city in the cloud. The underground city is the utility corridor laid beneath

major roads and will carry water and electricity mains and space for automated

logistics delivery. The “city in the cloud” refers to Xiongan’s

digital twin, a virtual digital copy built alongside the actual city’s

construction. This digital twin is supposed to allow for better real-time

traffic navigation, better infrastructure and technology systems maintenance,

and algorithm-driven management of traffic and other urban systems. Similar

systems have been piloted in other Chinese cities to control traffic, for

example, relying on pervasive surveillance

technology. Yet the

use cases of Xiongan’s digital twin and 5G-powered

autonomous vehicles have not yet been deployed from the ground up at the scale

of an entirely new city like Xiongan.

Such large-scale

infrastructural systems enable the trialing and showcasing of new technologies

on a scale unseen in most new city projects. Xiongan

has also been a testing ground for China’s efforts to establish a new digital renminbi. This central bank digital currency could

ultimately reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar and allow the government to

collect data on consumer transactions. Construction workers in Xiongan have received wages via digital blockchain currency, thus

incentivizing adoption even as most consumers have been slow to embrace the

digital renminbi.

If Shenzhen signaled

China’s experimentation with market reforms under Deng Xiaoping, then Xiongan represents a partial reversal. Today, the

phrase Xiongan zhiliang (“Xiongan quality”) is used to describe the city as a symbol of

“high-quality development,” a term that emerged in 2017 during the 19th Party

Congress to signal China’s progression away from heavy manufacturing to an era

of so-called cleaner knowledge-intensive growth. It also references the

term Shenzhen sudu (“Shenzhen

speed”), which was used to describe Shenzhen’s rapid growth as one of China’s

first special economic zones in the 1980s.

In addition to its

emphasis on innovation, the city’s design has social engineering goals. Xiongan’s plan calls for putting social and cultural

facilities at the heart of urban life, reflecting the importance that the

Chinese Communist Party has placed since 2014 on promoting a more

“human-centered” urbanization. Urban design guidelines call for new

“five-minute blocks,” allowing residents to access community medical clinics,

child and elder care facilities, and a range of other one-stop services within

a five-minute walk, and for “cultivating a new Xiongan

person with a healthy mind, noble character, and artistic temperament.” If

implemented, this plan would recenter the party’s presence in everyday urban

life while streamlining and modernizing the image of government bureaucracy.

Xiongan’s design also infuses elements of traditional Chinese

culture into modern architecture, reflecting Xi’s emphasis on “cultural self-confidence.” The Xiongan New Area

Management Committee ordered “three no-builds in Xiongan—no

high-rise buildings, no cement forests, no glass curtain walls.” While there

will be some high-rises, heights will be controlled in most areas. Xiongan may be Xi’s Shenzhen or Pudong, but in style and

form, it is the opposite.

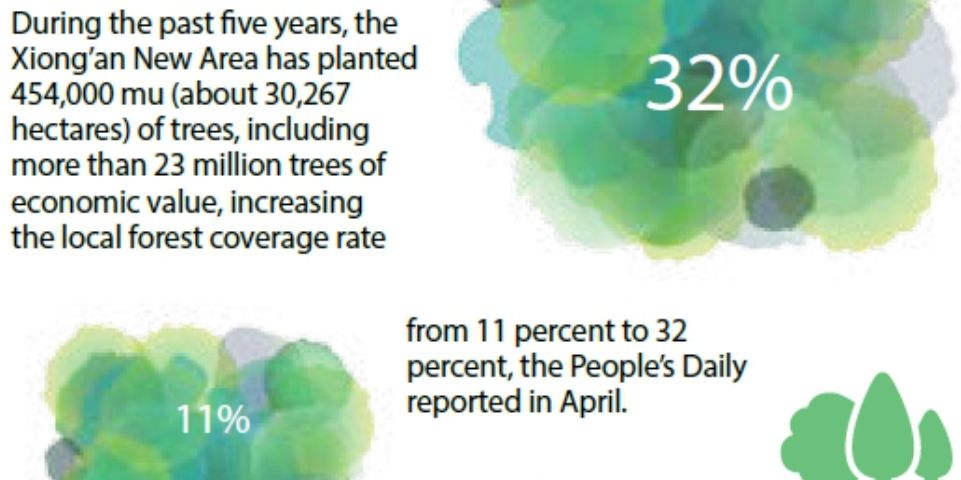

Environmental quality

is a large part of Xiongan’s symbolic power.

Recognizing that toxic pollution had threatened the party’s legitimacy, the

State Council issued new urbanization guidelines in 2014. Xiongan

is the crystallization of this. Energy is to be generated from various

renewable sources. Public transport is planned to shoulder 90 percent of traffic.

Autonomous electric vehicles will operate with intelligent sensing cameras that

will allow them to navigate the city’s streets. Media reports claim that the Baiyangdian

wetlands have been revitalized through pollution removal and habitat

restoration.

Several buildings

nearing completion communicate this fusion of nature, high technology, and

elements of traditional Chinese culture: The city's brain data center floats on

a body of water surrounded by greenery that will cool the servers and moderate

the energy required for the operation of cloud computing servers. A power

transforming station built by China State Grid features a Chinese-style garden

on its roof. A recent CCTV documentary described the building of “shan shui city style, integrating

practical use and aesthetics.” This references the classical Chinese painting

tradition of water and mountain landscapes. The message is that high-tech

innovation doesn’t have to come at the expense of the environment or public

health and that China can innovate on its terms.

There have been

discussions in Xiongan about implementing new affordable

and subsidized housing models. But a former employee of one of the state-owned

developers involved in Xiongan told me that he

thought, ultimately, there would be a mix of housing types, including

subsidized rental units and homes for purchase. Rongdong,

Xiongan’s first phase, has mostly comprised

resettlement housing for villagers whose homes were destroyed to make way for

the city’s construction. This continues a nationwide policy of eradicating

rural poverty by relocating villagers to new apartment blocks—although this

often fails to reduce poverty and creates new problems.

Given Xi's centrally

led investment and personal commitment, it would be unwise to write off the Xiongan experiment. The city is the latest example in

China’s long history of using model cities to communicate political ideals,

from the socialist oil city of Daqing in the 1950s to Deng’s Shenzhen as a

testing zone of market reforms in the 1980s. If the city takes off, private

companies may want to move there to tap into what could be a cluster of

high-tech talent and resources. But until then, central government support will

be the main source of resources and capital. Though the city has been called a

“thousand-year project,” the next few years will be a critical period for Xiongan and Xi’s larger vision of party-state-led

innovation.

For updates click hompage here