By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Overview Of The Arab-Israeli War

As the conflict reached the

one-year mark, Israel has overwhelmingly used aerial operations, hammering

Lebanon and testing Iranian intentions. (Iran responded with an aerial

bombardment in kind.) Here again: All of this has value, but none of it can

eliminate an enemy or overtake cities that contain command centers,

intelligence, and weapons. Destroying what remains of Hamas or Hezbollah by air

will not cripple their ability to wage war. If it didn’t work against Nazi

Germany, it certainly won’t work against a decentralized insurgent force.

This unsophisticated

view applies to Israel’s enemies too. To win, Hamas and Hezbollah have to focus

on Israel’s ability to fight, and what Hamas has done heretofore has been

counterproductive in that regard. It tipped its hand by showing the threat it can

pose without crippling Israel’s ability to fight.

Israel’s apparent war

plan, then, raises an important question. Is Israel fighting to protect itself

or to defeat its enemies? Both are reasonable choices, but how the Israelis

answer that question will define their military strategy. The key to war is knowledge

of what victory looks like, and the key to victory is to render the enemy

helpless. The only sure way to achieve this is to envelop and crush the enemy.

By themselves, missiles can’t do that. Militarily, this is something Israel

should bear in mind as ground troops advance in Lebanon.

Politically, the

clock is ticking. Russia – directly or indirectly the United States’ adversary

in the Ukraine war – has an interest in how the Arab-Israeli war plays out.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has already discussed visiting Qatar, which

has a reputation for being interested in aligning with Russia. (Qatar has

confirmed its interest but has issued no dates for a Putin visit.) Russia has

much to gain from the United States’ prolonged involvement in a conflict

already spreading to another country.

Wars that go on too long tend to end with many

casualties and unexpected costs – if they end at all. War is complex;

combatants must simplify the fight to a ruthless focus on defeating the

enemy. An annual DHS assessment

released Wednesday describes why the clock is ticking.

Thus, two major wars are

being fought. One, between Ukraine and Russia, has been raging for more

than two and a half years but has been roughly confined to Ukraine. The other,

between Israel and Hamas, has been ongoing for almost a year but is expanding

dramatically. Combat recently intensified northward into Lebanon.

It is like war to

grow. When two forces clash, static warfare often shifts to maneuver warfare as

each side seeks to flank the enemy and stretch its defenses to their breaking

point. As wars progress, flank attacks and large-scale offensives become more likely,

increasing the demand for supplies. What began as a limited engagement grows in

both scale and definition. The logic of war takes hold. Maneuvering increases,

supply lines lengthen and reveal vulnerabilities, and maps of the conflict are

redrawn, leading to geographic expansion.

The war in Ukraine

has been relatively contained thus far, largely limited to the area between

Russia’s assault and Ukraine’s evolving defense. However, the second war, which

began last October when Hamas attacked Israel, has been transformed by Israel’s

move to attack Hezbollah in Lebanon. This will not be a conventional,

infantry-led conflict with defined lines of engagement. It will continue as it

began: with Israel trying to destroy the enemy’s command structure, while

Hezbollah and Hamas attempt to put the Israeli population at risk. In this

conflict, the pursuit of advantage and surprise will encourage expansion – a

particularly acute risk given the war’s proximity to Ukraine.

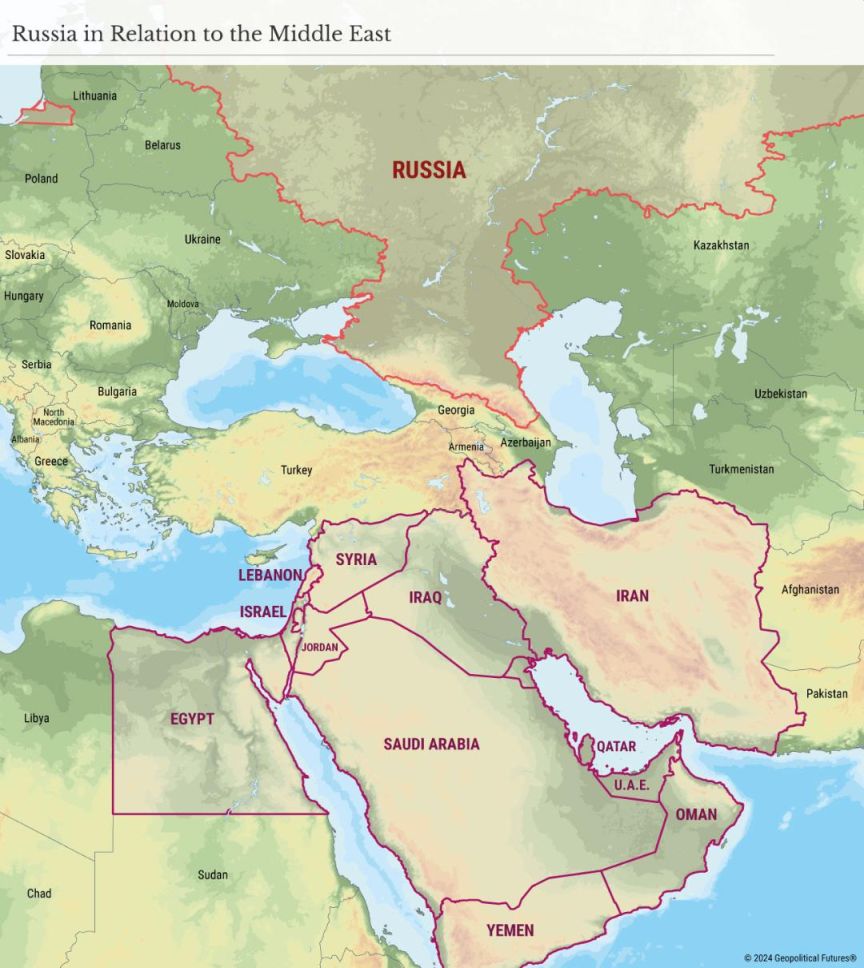

The Israeli-Arab war is likely to move northward and

eastward toward Iran and Central Asia. If this happens, Russia will need to

dramatically increase its military presence to manage the danger to itself,

especially after the Islamist terrorist attack several months ago against a

Moscow theater. Russia would not be able to maintain an active defense against

a northward move.

While Israel would

have an ally in Russia, the instability to the north would allow Iran to

increase its power. Israel would become cautious in such a scenario, avoiding a

clash with Turkey but engaging in high-intensity combat. This northern

expansion would stretch Israel’s military, limiting its ability to maneuver and

reducing its influence over the conflict.

Russia’s interests

extend beyond Ukraine, including growing concern about threats along Russia’s

southern border. Meanwhile, Israel’s smaller force size and logistical

challenges limit its ability to sustain long-range operations. Without

neutralizing immediate threats, Israel cannot afford to disperse its forces

northward. In a way, this expansion would narrow Israel’s strategic options

while fueling a broader Russo-Arab war.

This may seem

far-fetched, but humanity’s tendency to overestimate its ability to control

mass violence is thoroughly documented. The U.S. experience in Afghanistan is

just one example. Wars are rarely static, and the geography and availability of

forces in this case make an extremely improbable evolution more likely.

Russia is already

engaged in a major conflict, but the northward shift of the Israeli-Arab war

may lead Moscow to take steps it hadn’t anticipated. It’s unlikely, certainly,

but the U.S.-Soviet alliance in World War II was also unlikely. As for the

United States, it has developed a national strategy of arming allies but

avoiding direct combat. The United States spent a long time learning this rule,

and it seems that regardless of the coming elections, it will continue to

follow it.

For updates click hompage here