By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Cold War part one

There are different versions about when the Cold War

would have started, there is the Western version which we will mention underneath,

yet this contrasts with the version that is thought in Russia including as

thought to all Rissian diplomats and graduates of

the Foreign Intelligence Academy of the SVR (Foreign Intelligence

Service).

The story they are thought is that the Cold War

started following a coup orchestrated by the US and the UK to topple the

Lenin regime and kill Lenin. This idea was started by Secretary of State

Lansing when he told President Wilson on 10

Dec. 1917 that the only hope for Russia lay in setting up a “military

dictatorship.” Lansing’s idea was to choose one man and make him the boss of

Russia on the side of America and the Allies. And in turn, David R. Francis,

the American ambassador to Russia, asked

Washington for 100,000 troops to take Petrograd and Moscow to support the

coup against Lenin.

And while the Cold War later in the West became a time

of tension, fear, and danger, but because it ended in ‘victory’ for the West,

it came to be viewed with nostalgia, last week Britain's army

chief General Nick Carter as reported by the BBC explained

that there is a greater risk of an accidental war breaking out between the

West and Russia than at any time since the Cold War, with many of the

traditional diplomatic tools no longer available.The

risk of an accidental war breaking out between Russia and the West is greater than at

any time during the Cold War, Britain's most senior military officer has

said in an interview with Times Radio.

This ( nostalgia

aside) made us decide to revisit and take a close look at what started the

previous cold war and what we can learn from it for when the next one according

to General Nick Carter might start.

For a millennium, Russia has been an autocracy with power

concentrated in the hands of an all-powerful leader or leadership group. The

strong centralized rule has held together with a disparate, centripetal empire

and preserved it from the predations of powerful foreign enemies. Sporadic

attempts at democracy have ended in a return to the same default mode of

governance; the cause of the state has taken priority over the interests of the

individual.

Tsarist Russia and

Weimer Germany were failing states before either Lenin or Hitler came along.

But that does not mean their victories were foregone conclusions. Neither man

had ever run anything; their immediate

supporters hadn't either.

By summer 1921,

around 27 million people in Russia were dying from starvation, including some 9

million children.

Maxim Gorky, a

Russian writer and independent Marxist who had been exiled by Lenin for

opposing the Soviet dictatorship, sent his own appeal.

J. Edgar

Hoover replied to Gorky, saying

certain conditions would have to be met before U.S. aid could be sent: All

Americans had to be freed. American relief workers had to have complete freedom

to do their jobs. Distribution would be on a non-political basis. The relief

workers would need free transportation, storage, and offices.

Lenin stalled. He was convinced the aid

workers, would-be spies.

The history of the

twentieth century, worldwide, was marked by the two world wars. The Russian Revolutions of 1917 were a consequence of the First World War, the Cold War of the Second.

For a millennium,

Russia has been an autocracy with power concentrated in the hands of an

all-powerful leader or leadership group. A strong centralized rule has held

together with a disparate, centripetal empire and preserved it from the

predations of powerful foreign enemies. Sporadic attempts at democracy have

ended in a return to the same default mode of governance; the cause of the state has taken priority over

the interests of the individual.

The term "Cold

War" itself was first used by the English writer George Orwell in an article published in 1945 to refer to what

he predicted would be a nuclear stalemate between “two or three monstrous

super-states, each possessed of a weapon by which millions of people can be

wiped out in a few seconds.” It was first used in the United States by the

American financier and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch in a speech at the State House in Columbia,

South Carolina, in 1947.

Churchill was more

concerned with Eastern Europe than was Roosevelt, and not only because he felt

that Britain owed something to a heroic and tragic Poland.

He knew the history

and the geography of Europe: he was concerned with Austria, Hungary,

Czechoslovakia, rather than with Romania and Bulgaria. The last two had been

often dependent on imperial Russia, while the others belonged to Central,

rather than Eastern, Europe (As late as December 1944 he wrote to Roosevelt

about that distinction.) But his powers were limited.

Conferences in Yalta

in February and Potsdam in July 1945 were intended to secure a sense of lasting

global peace and a new, functioning system of international cooperation, but

they took place against this background of hurt and resentment. The British,

Americans, and Soviets had been thrown together in a somewhat unlikely wartime

alliance, and only common effort and common sacrifice had advanced it from a

matter of convenience to a relationship of nascent respect. By 4 February 1945,

when Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill gathered in Yalta’s Livadia

Palace, there was a certain willingness not to throw away the gains that had

been made.

But history is not

always made through the logical development of policy. Policies are made by men

and women, and the personalities of the leaders of the Big Three Allied powers

and the interactions between them would do much to determine the shape of the

postwar world, at times retreating from, at times hastening, the advent of the

Cold War. Stalin had taken a conscious decision to use charm and cunning to

extract what he could from the face-to-face discussions with his fellow

leaders. At times he would be aggressive, at others conciliatory, but always

focused on achieving his goals. Roosevelt and Churchill, the latter from an

increasingly weakened position, had other aims and other negotiating styles. In

this clash of wills and egos, history would judge that the British and

Americans allowed themselves to be bullied and intimidated by Stalin.

Each of the three leaders brought his demands.

Stalin’s most pressing goal was to retain his vast territorial gains in Poland

and install a pro-Soviet government in the country. This was to cause much wrangling

over the days that followed and dominated the agenda for seven of the eight

plenary sessions. The Soviet leader held the upper hand, for his troops had

already overrun eastern and central Europe, with much of Poland,

Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary under Red Army control.

President Roosevelt had two principal aims: to persuade

the Soviet Union to join the war against Japan, which proved so costly in American

lives, and to cajole Stalin into accepting his proposals for a new

organization, the United Nations. He believed that such a body was the only

means of avoiding future global conflict.

Churchill’s overriding goal was to preserve the

integrity and status of both Great Britain and her empire, which still ruled

over a quarter of the world’s population. He also had strong views on Poland,

on whose behalf Britain had first declared war on Nazi Germany. Above all else,

he was determined to prevent postwar Europe from being dominated by the Soviet

Union.

Stalin appeared in fine humor, yet

behind the smiling facade was an ingrained distrust of both Churchill and

Roosevelt. Just a few months earlier, he had described the British prime

minister “as the kind of man who will pick your pocket of a kopeck if you don’t

watch him!” As for the American president, Stalin said that Roosevelt “dips his

hand only for bigger coins” It was an apt metaphor coming from one who had

robbed a bank in his twenties. When Stalin stole, he did so on a grand scale.

America’s ambassador to the Soviet Union, W. Averell

Harriman, sensed a peculiar dynamic between the two men. “I think Stalin was

afraid of Roosevelt,” he said. “Whenever Roosevelt spoke, he watched him with a

certain awe. He was afraid of Roosevelt’s influence in the

world.” Harriman noted that Stalin never displayed the same sense of awe

when talking with Churchill.

Stalin had good

reason to feel confident. In the weeks before the conference, Soviet

intelligence had supplied him with copies of the British strategy documents for

the meeting. It meant Stalin knew London’s aims and weaknesses, and he knew the

negotiating strategy Churchill planned to adopt. Correspondence between

Churchill and Roosevelt, provided by the Cambridge spies Guy Burgess and Donald

Maclean, revealed the western Allies’ disagreements about the postwar Europe

they wanted to see. Forewarned, forearmed, Stalin held the psychological

advantage and used it to decisive effect.

He knew, in

particular, that the Americans and British were unsure about the solidity of

their alliance and divided on their postwar aims. And he knew that the British

feared the Soviet military might enough to avoid confrontation on some of the

key divisive issues that would arise.

In Jill Rose’s

Nursing Churchill: Wartime Life from the Private Letters of Winston Church

ill’s Nurse Doris Miles speaks of him strolling down the corridor ‘with only a

towel around him. Another of his nurses, Dorothy Pugh, records similar

instances in her wartime diary. Terry Waite recalls, ‘We had a conversation in

which she [nurse Pugh] mentioned that she had been the Matron to Churchill. She

told me that Churchill wore the pajamas of that period with the open fly, which

sometimes showed his private parts, and she would say, “Put it away, Winnie!” I

feel they had a great closeness, God rest her soul.’ Commenting

in ‘A Unique WWII Archive from Churchill’s Nurse’.

Soviet intelligence

reports, some accurate, others exaggerated, deepened Stalin’s mistrust. His

responses grew increasingly vehement. He made threats that were in turn viewed

by the West as disproportionate and antagonistic. The self-amplifying cycle of antipathy

pushed Washington and London towards the very hostility that Stalin had begun

by imagining in them.

Churchill could no

longer dismiss Stalin’s behavior as harmless. He wrote to him with a stark

warning of the future that would emerge from a breakdown in East-West trust.

At Yalta in February 1945, Winston Churchill, a dying

Franklin Roosevelt, and the cagey Joseph Stalin carved up Germany, with the

Russians taking the eastern half and the Allies dividing up the West.

The carving up of Germany took place on 1 August 1945

at Potsdam with the signing of the Potsdam

Protocol by President Harry S.Truman,

Prime Minister Clement Attlee, and Marshal Joseph Stalin, provisionally only

until the signing of a peace treaty between the involved countries. At this

point, Russia took over the northeastern part of East Prussia with

Königsberg/Kaliningrad, Poland annexed the rest of East Prussia plus Pomerania,

Eastern Brandenburg, and all of Silesia while Czechoslovakia annexed the

Sudetenland, in all, 1/3 of autonomous prewar German territory.

The post-WWII German-Polish border was drawn southward

from the Baltic along the Oder and Neisse rivers. Even though Pomerania’s

capital Stettin/Szczecin (the birthplace of Catherine the Great, born in 1729

in Stettin) lies on the western side of the Oder river and consequently should

still be German, it is today a Polish harbor city.

Despite occasional outbursts, the meeting at Yalta had

been conducted in an atmosphere of goodwill. Potsdam, according to Hugh Lunghi,

was ‘a

bad-tempered conference’. The alliance of personalities, the human glue that

held things together when politics were tearing them asunder, was dissolving.

Roosevelt was dead; within a few days, Churchill would be out of office,

replaced by Clement Attlee. By the end of the Potsdam gathering, only Stalin

would remain from the wartime Big Three leaders.

Late in February 1946, George Kennan, the No. 2

at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, sent his momentous “long telegram” to the State Department

analyzing Stalin’s malign designs on Europe and sketching a containment

strategy. A few weeks later, Churchill ventured to Missouri to give his epochal

speech: “From

Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste on the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended

across the Continent.”

Stalin made the diplomatic wrangling moot 18 months

later when the Soviets abruptly sealed off the roads and railways linking

Berlin to the West and cut off sources of food, clean water, electricity, coal,

and medicine from the east. The blockade meant starvation for the citizens of

West Berlin and was designed to force the Allies to abandon the capital.

After using nuclear weapons against Japan, he would

send an urgent message to the managers of the Soviet atomic program. ‘Hiroshima

has shaken the whole world. The balance has been broken. Build the Bomb – it

will remove the great danger from us.’ In the minds of many Soviet

citizens, the demonstration of western nuclear might represented an imminent

threat.

In August 1959, with his second term nearing its end,

Eisenhower made the surprise announcement that he and Soviet premier Nikita S.

Khrushchev would visit each other’s countries as a means of “thawing some of

the ice” of the Cold War. Khrushchev’s trip to the United States in September

1959 resulted in plans for a four-power summit involving Great Britain and

France and for Eisenhower’s visit to Russia in early summer 1960. Then, in May

1960, the Soviet Union shot down an American U-2 surveillance plane piloted by

Francis Gary Powers. The ensuing collapse of the summit and the subsequent

cancelation of Eisenhower’s trip to the Soviet Union amounted to a critical

missed opportunity for improved US-Soviet relations at a crucial juncture in

the Cold War.

Eisenhower’s prestige within the Soviet Union was so

great, and the trip, if it had happened, could well have led to a détente in

the increasingly dangerous US-Soviet relationship. Instead, the cancelation of

Ike’s visit led to an escalation in hostilities that played out around the

globe.

This led to the formation of NATO, the founding of the

West German federal republic, with Konrad Adenauer

as its first chancellor, and eventually, the unification of a Germany firmly

allied with the Western democracies against Russian expansionism: the world as

we know it today.

FDR and Churchill negotiated much of the end of the

war at Yalta. Neither would see Potsdam through to the end. FDR died in office,

and Churchill was voted out of office.

The Cold War thus began as a competition between

capitalist and communist governments to expand their social contracts as they

raced to deliver their people a better life. But the economic shocks of the

1970s made promises of better living untenable on both sides of the Iron

Curtain. Energy and financial markets placed immense pressure on governments to

discipline their social contracts. Rather than make promises, political leaders

were forced to break them.

In the West, neoliberalism provided Western leaders

like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher with the political and ideological

tools to shut down industries, impose austerity, and favor the interests of

capital over labor. But in Eastern Europe, revolutionaries like Lech Walesa in

Poland resisted any attempt at imposing market discipline. Mikhail Gorbachev

tried to reform the Soviet system in vain, but the necessary changes ultimately

presented too great a challenge.

Faced with imposing economic discipline antithetical to communist ideals,

Soviet-style governments found their legitimacy irreparably damaged. But in the

West, politicians could promote austerity as an antidote to the excesses of

ideological opponents, setting the stage for the rise of the neoliberal global

economy.

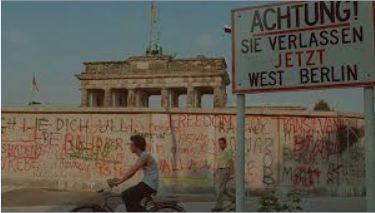

To stop this, access to the West through West Berlin

had to be cut off. In August 1961, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev authorized

East German leader Walter Ulbricht to begin constructing what would become

known as the Berlin Wall. The wall, started on Sunday, 13 August, would

eventually surround the city, despite global condemnation, and the Berlin Wall

itself would become the symbol for Communist repression in the Eastern Bloc.

It also ended Khrushchev’s attempts to conclude a peace treaty among the Four

Powers (the Soviets, the Americans, the United Kingdom, and France) and the two

German states.

The CIA recognized the impact the Wall would have on

their work in Berlin. The possibilities for obtaining information deteriorated

significantly by September 1961, and the CIA feared morale would drop among its

employees in the city. The staff of Berlin Operations Base (BOB) was to be

reduced from around 95 to 75. The importance of BOB as an outpost in hostile

territory diminished after 1961. This was especially true of what the Americans

and the British called HUMINT (human intelligence), namely gathering

intelligence by agents. Reconnaissance flights by the American U-2 spy plane

over the Soviet Union had been undertaken since the mid-1950s with great

success. As will be seen, other indications of the changes taking place in the

gathering of intelligence were the construction of the Berlin spy tunnel and

the erection of large listening stations in the city. The focus on the human

being as a source of information, as a secret agent, began to wane.

Technological progress meant that telecommunications and electronic

surveillance became the most essential tools of espionage.

When Gorbachev became

general secretary in March 1985, following the death of the final interim

leader, Konstantin Chernenko, he inherited the Soviet Union in economic and

spiritual decline.

The first of their

five summit meetings would take place within eight months of Gorbachev assuming

office. ‘Time

is short,’ he told Dobrynin. ‘We need to get to know Reagan and his plans,

and most importantly, to launch a personal dialogue with the American

president.’ The emphasis on personal rapport was new. Previous general

secretaries had lacked anything approaching a personality and had been too

sick, or their time in the post too short, for a meeting to be arranged with

Reagan. Meeting face to face, Gorbachev told Reagan, could ‘create an

atmosphere of trust between our countries … For trust is an especially

sensitive thing, keenly receptive to both deeds and words. It will not be

enhanced if, for example, one were to talk as if in two languages: one – for

private contacts, and the other … for the audience.’1

When they met again a

year later, in Reykjavik in October 1986, they were pals, calling each other by

their first names and – astoundingly – giving serious thought to the

dismantling of all nuclear weapons within ten years. The deal might have been

struck, had Reagan not insisted on the right to continue the development of

SDI. Gorbachev tried to look on the bright side. ‘In spite of all its drama,

Reykjavik is not a failure,’ he told the final press conference. ‘It is a

breakthrough, which allowed us for the first time to look over the horizon.’2

Many high officials

struck up warm relations, too, in a way that was largely unthinkable in the

recent past. The only people who did not get along were Raisa and Nancy.3

Gorbachev had gambled

on his relationship with the West. He had banked on securing concessions for

the Soviet Union in exchange for allowing the peaceful collapse of socialism in

eastern Europe. But he had misread the psychology of the Cold War. The brief

interlude of warm personal relations with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher

persuaded him that the West might offer the USSR a way out of its dire economic

and social predicament. But four decades of entrenched hostility could not be

wiped away. With the communist monster at their mercy, the western powers were

hardly going to take their foot off its throat.

Gorbachev was

surprised and affronted when the Americans rejected his request for big loans

to help perestroika succeed. He complained that Bush had left him and the

Soviet Union ‘to stew.’ But Gorbachev’s indignation, Anatoly Chernyaev wrote, was ‘the wail of a desperate man whose

control over his country was visibly slipping away – of one who no longer

understood what he was trying to achieve.

Three decades after

the Cold War ended, the hopes for a new and more cooperative era in world

politics have been lost. With the rise of China and the resurgence of Russia,

today, there are once again global powers rivaling those of the West. We are

now in a Second Cold War, and international security is under threat.

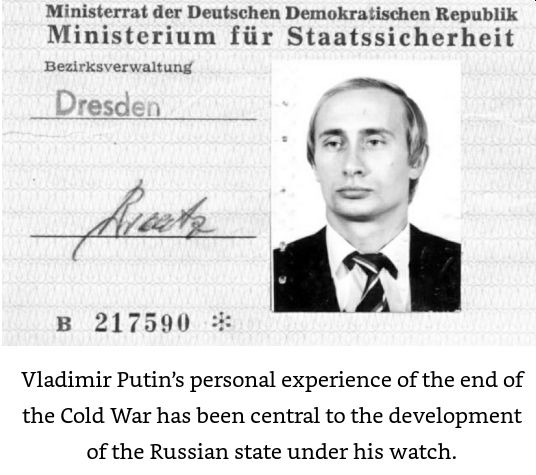

The Soviets had their

own James Bonds. The hero of the 1974 film The Starling and the Lyre battles a

western plot to sow discord between the USSR and her allies, makes long

speeches about the US military-industrial complex, and enjoys a weepy romance

with a female spy. In The Shield and the Sword, a title is drawn from the KGB’s

service emblem (overleaf), secret agent Belov is pitched into action against

the Nazis. By the time of his fourth film appearance, he was the poster boy of

Soviet postwar espionage in the minds of millions, including that of the

sixteen-year-old Vladimir Putin, who went straight from the cinema to volunteer

his services to the KGB.

Continued in part

two.

1. Anatoly Chernyaev, Notes from the Politburo Meeting, 21 January

1989, trans. Svetlana Savranskaya, The Archive of the

Gorbachev Foundation, Cold War International History Project, Virtual

Archive, CWIHP.

2. See

‘Gorbachev: his life and times, William

Taubman in discussion with Vladislav Zubok.

3. D. Reynolds,

Summits: Six Meetings that Shaped the Twentieth Century, London, Allen Lane,

2007, p. 193.

For updates click homepage here