By

Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

The Cold

War part two

Having earlier taken a deep dive into Russian

history decided to take a close look at the

dynamics of the Cold War and the making of Putin.

The Bay of Pigs invasion and the coming

of Gagarin.

The Bay of Pigs

invasion, for those who stormed a small stretch of the Cuban coastline on

April 17, 1961, was a turning point in the fight against an oppressive

communist regime, one that, some argue, still carries an outsized impact

on national elections in the United States. Those who survived the

beach landing and the subsequent wave of executions, over a thousand men, were

held in Castro’s jails for a year and a half before being exchanged for a $53

million ransom

of baby food and medicine from Washington.

The Cuban fiasco infuriated

Kennedy. In public, he took responsibility; in private, he lambasted the

military and the CIA for persuading him that the operation had a chance of

success. The CIA director, Allen Dulles, and members of his senior staff took

early retirement. While Fidel Castro and Ché Guevara

looked on with glee, Nikita Khrushchev cabled from Moscow to say that the USSR

would not allow the US to enter Cuba, hinting that a further attempt would

bring nuclear retaliation against US cities. The Bay of Pigs made America look

mendacious, untrustworthy, and – worst of all – incompetent and weak.

From a beleaguered

White House, John Kennedy watched the Soviet rejoicing and came to a decision

that would define his presidency. ‘The adversaries of freedom possess a

powerful intercontinental striking force, large forces for conventional war,

and long experience in the techniques of violence and subversion,’ he told the

US Congress on 25 May. ‘It is a contest of will and purpose as well as force

and violence, a battle for minds and souls as well as lives and territory. And

in that contest, we cannot stand aside.’ The priority was to win the present

war of nerves in order to avoid ceding the commanding

heights in a future war of arms.

Meanwhile, Yuri

Gagarin (the first human in space) was on a global tour, visiting Brazil,

Bulgaria, Canada, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Finland, Great Britain, Hungary,

Iceland, and India. More than a million people lined the streets of Calcutta to

greet him.13 In Britain, he mingled with factory workers in Manchester and met

Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace. The Times reported that he received ‘a

welcome bordering on hysteria’.

The fulfillment of John

Kennedy’s 1961 promise to ‘land a man on the Moon and

return him safely to Earth’ marked the finishing line in the space race. In the

intervening years, both the military and the psychological balance had tilted

in Washington’s favor. The time seemed to have come for cooperation to replace

rivalry. As early as the Vienna summit of 1961, Kennedy had

proposed a joint space mission with the Soviets, and he did so again in

a speech to the UN General Assembly on 20 September 1963. Soviet self-assurance

at the time and Kennedy’s assassination two months later meant a joint Moon

mission would not happen. But contacts at the level of science – and between

astronauts and cosmonauts – continued.

Neil Armstrong met with Yury

Gagarin’s widow after the Soviet cosmonaut’s untimely passing. He was also

the first foreigner to set foot in the hypersonic “Soviet Concord” and even had

the opportunity to cook ukha soup on the shores of

the Siberian “sea”.

As we have seen Gorbachev next gambled on

his relationship with the West. He had banked on securing concessions for

the Soviet Union in exchange for allowing the peaceful collapse of socialism in

eastern Europe. But he had misread the psychology of the Cold War. The brief

interlude of warm personal relations with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher

persuaded him that the West might offer the USSR a way out of its dire economic

and social predicament. But four decades of entrenched hostility could not be

wiped away. With the communist monster at their mercy, the western powers were

hardly going to take their foot off its throat.

Well covered in

Michel Eltchaninoff’s Dans la tête de

Vladimir Poutine (2015; translated as Inside the Mind of

Vladimir Putin, 2018). According to Eltchaninoff,

Putin told Paris Match in 2000 that he “loved to read the

Russian classics, especially Dostoevsky and Tolstoy”. All very vague, of

course, but in 2006 when Putin unveiled a statue to Dostoevsky in Dresden, site

of his former KGB posting, he stressed that Dostoevsky’s message had been human

harmony and that the present occasion signified “that we live in a unified

European cultural space”. The positive post-Cold War sentiment echoed

Gorbachev’s 1987 formulation of “our common European home”.

In December 2000,

Vladimir Putin marked the first anniversary of his ascent to the Russian

presidency by bringing back the old Soviet national anthem. It is a rousing

patriotic hymn that stirs emotions, but its identification with the era of

communism meant there were protests at its reinstatement, albeit with new

words.1 Putin justified his decision in a long-unpublished interview with the

filmmaker Vitaly Mansky. ‘I was in Ulyanovsk,’ Putin says on camera, twenty

years ago!’ Well, what can you say to that? To go back is impossible. Neither our youth nor the old days

can ever return. But it is essential to rebuild people’s trust in their

leaders. You need to make people feel that not everything has been snatched

away from them. The vast majority of the population

feels nostalgic for that time [the Soviet era]. You can’t simply take

everything away from them. I think of my parents, this part of their lives. Can

we just throw all this away, root and branch, as if they never lived? (Mansky’s

interview with Putin was recorded in 2000 and included in his 2018 film Svideteli Putina (‘Putin’s

Witnesses’).

The old certainties

were gone. The old world had vanished. In East and

West alike, people faced an unsettling psychological challenge of adaptation.

When Bill Clinton struggled with the ambiguities of modern international

relations during the 1993 Somalia crisis, he exclaimed, ‘Gosh, I miss the Cold

War!’2 In the new era of uncertainty, memories of the past would be recast and

at times manipulated. They would be deployed by politicians, writers and

agitators for purposes of reassurance and of deception. George Kennan proved to

be a shrewd analyst of the Russian character. As early as 1947, he had

suggested that it had become distorted under the Soviet system, leaving

precarious psychological foundations. ‘The present generation of Russians have

never known spontaneity of collective action,’ Kennan warned in his article

‘The Sources of Soviet Conduct’. ‘If, consequently, anything were

ever to occur to disrupt the unity and efficacy of the Party as a political

instrument, Soviet Russia might be changed overnight from one of the strongest

to one of the weakest and most pitiable of national societies.’3 The end of the

Cold War and the collapse of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union would

demonstrate how right Kennan had been. Millions in Russia were left without

savings, without jobs, and without hope, bereft of any conception of what their

lives now meant. The land they had called their home, the social and political

ideals to which they had dedicated their existence, had vanished overnight. ‘It

seems to me that we lack an aim,’ lamented Natalya Pronina, one of many who

felt lost in the new Russia. ‘If before we had a goal, communism – even if it

was an unobtainable one – we at least had a purpose. However, there’s none

now.’4 Their society had failed, so they too had failed. Memories became

meaningless – bitter reminders that they had been part of an evil age. It is

not hard to understand why so many of the older generation clung forlornly to

an idealized version of the past, desperate to rehabilitate it – and themselves.

The man they blamed for destroying their country and blighting their lives

struggled to rationalize what he had done. Mikhail Gorbachev was torn between

the adulation he received from a grateful West and contrition for the suffering

of his countrymen. In 1992, he spoke from the same podium in Fulton, Missouri,

where Winston Churchill had given his ‘Iron Curtain’ speech forty-six years

earlier. The end of the Cold War, Gorbachev suggested, could offer an

opportunity for worldwide reconciliation, a new paradigm in which ‘the idea

that certain states or groups of states could monopolize the international

arena is no longer valid’. To reach ‘the exalted goal’

of peace and progress for all, however, would require greater wisdom than had

been shown in 1945. The Cold War had been presented to people in East and West

as ‘the inevitable opposition between good and evil – with all the evil, of

course, being attributed to the opponent’. Now both sides would need to

‘dispense with egoistic considerations’ in order to

secure a better future.5

Gorbachev was in

denial. Haunted by the harsh fate his actions had inflicted on his homeland, he was appealing for the same concessions from the

West that he had failed to win when he had cards to play and reciprocal

concessions to offer. Now he was out of power and impotent: America was hardly

likely to ‘dispense with egoistic considerations’, however eloquently Gorby

pleaded. On the contrary, George H. W. Bush had placed national egotism and a

world in which ‘certain states [i.e. the USA] would monopolize the

international arena’ at the top of his to-do list. ‘For the Cold War didn’t

end; it was won,’ Bush told the US Congress. ‘We are the United States of

America, the leader of the West that has become the leader of the world … Moods

come and go, but greatness endures.’6 In Bush’s telling, humanity had reached

the End of History: American ideals of liberal democracy and capitalism had

triumphed; from now on, it would be a unipolar world.

Gorbachev was not

alone in appealing to Washington to be magnanimous in victory. Pope John Paul

II, himself a long-standing

opponent of communist oppression in his Polish homeland, called on the West

to respond constructively to the end of the Cold War, to ‘avoid seeing this

collapse of communism as a one-sided victory of their own economic system and

thereby failing

to make the necessary corrections in that system’.8

The Cold War was a

time of tension, fear, and danger, but because it ended in ‘victory’ for the

West, it came to be viewed with nostalgia.

But the problem with

viewing the past as a righteous crusade is that it suggests there are no

lessons to learn from it. And a gloriously celebrated triumph makes what

follows a disappointment. Western figures whose formative years were lived in the good-versus-evil world of the Cold War

found it hard to adapt.

Soviet society had

followed the pattern of denial to the very last moments of its existence. The

Brezhnev years were founded on blocking out the legacy of the past and the

decay of the present. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, ready to

face reality, it was too late. The USSR experienced the fate that Karl Marx had

predicted for bourgeois capitalism. ‘All that is solid melts into air,’ Marx

and Engels had written in their Communist Manifesto. ‘And man is at last

compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his

relations with his kind.’20 The man who set about restoring Russia to what he

deemed its rightful place at the top table of international politics also had a

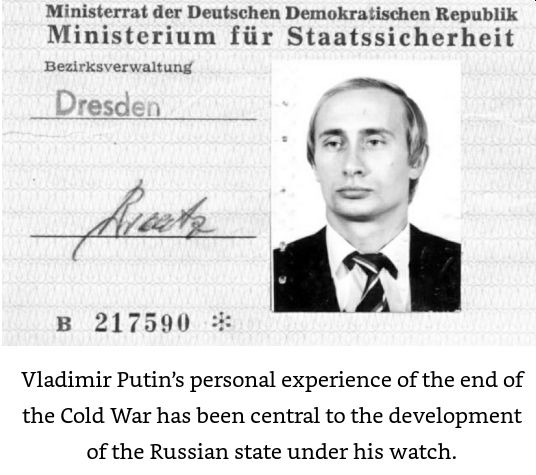

Stasi file. But Vladimir Putin’s record was as a perpetrator, not a victim.

Putin had been a KGB representative in East Germany in the late 1980s, posted

in Dresden in the so-called ‘Valley of the Clueless’ where West German TV could

not be received.

The suggestion is

that Putin must have slipped up to end up in such a relatively unimportant

post, and by his own admission, he spent

much of his time drinking beer.

Although he much

prefers to drink Dresden’s Radeberger Pilsner.

"Angela sends me some bottles of Radeberger beer

from time to time," says the

Kremlin chief in the film. Putin was previously stationed in Dresden as an

agent of the Soviet secret service KGB.

He would remember the

disintegration of the Soviet empire as a formative time in his life. His

official biography, produced in short order in 2000 to give the Russian people

an idea of who their new president was, helped explain why. It described a

dramatic episode in late 1989, when a baying crowd threatened to invade the

KGB’s Dresden headquarters. Putin, then a lieutenant colonel, tried desperately

to contact Moscow for guidance on what to do, only to be told that Gorbachev

was asleep and ‘we cannot do anything without orders’.

‘I got the feeling that the country no longer existed,’ Putin recalled. That it

had disappeared. It was clear that the Union was ailing. And it had a terminal

disease without a cure – a paralysis of power. Intellectually I understood that

a position based on walls and dividers could not last. But I wanted something

different to rise in its place. And nothing different was proposed. That’s what

hurt. They just dropped everything and went away.

Putin had lived

through events that can trigger what German psychiatrist Michael Linden described

as Post-Traumatic Embitterment Disorder (PTED). Closely related to PTSD, PTED

causes bitterness, hostility and aggression in sufferers following sudden

upheavals in their lives.

Deprived of the

cognitive schemata that had given shape to their lives, millions of people had

been left unable to find their place in the world.

Such emotions about

the chaotic state of post-Soviet Russian society may throw light on Vladimir

Putin’s behavior since coming to power at the end of 1999. Motivated by anger

at Gorbachev’s ‘betrayal’, he concluded that it was imperative to find ‘something

different’ if Russia were to survive one of the hardest periods in its

history.’ He feared that, without a vast effort, Russia would lose its place in

the top tier of global powers.

He witnessed

protesters occupying the Dresden Stasi headquarters, while communist security

forces came close to opening fire on them, on 5 December 1989.

Jubilant East

Berliners had already breached the Berlin Wall in November. Putin was

fluent in German at the time and has said he personally calmed the Dresden

crowd when they surrounded the KGB building there, warning them that it was

Soviet territory.

During his KGB

service in Dresden, Putin was promoted to the rank of lieutenant

colonel. In 1989 he was awarded a bronze medal by communist East Germany -

officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR) - "for faithful service to

the National People's Army", the Kremlin website says.

In June 2017 Putin revealed

that his work in the KGB had

involved "illegal intelligence-gathering". Speaking on Russian state

TV, he said KGB spies were people with "special qualities, special

convictions and a special type of character".

During the Munich

Security Conference of 2007, Putin stated: ‘I am here to say what I really

think about international security problems,’ he told his fellow world leaders.

Just like any war, the Cold War left us with live ammunition, figuratively

speaking. I am referring to ideological stereotypes, double standards, and

other typical aspects of Cold War bloc thinking. The unipolar world that had

been proposed after the Cold War is one in which there is one master, one

sovereign … the United States has overstepped its national borders in every

way. This is visible in the economic, political, cultural, and educational

policies it imposes on other nations. Well, who likes this? Who is happy about

this? A world order dominated by the US was bad for Russia, Putin said, but it

was equally harmful to America itself. He listed areas of concern including

western interference in other states, the West’s development of strategic

conventional military capabilities, US missile defense plans, and NATO

expansion and ‘aggression’. ‘At the end of the day this is pernicious not only

for all those within this system,’ he concluded, ‘but also for the sovereign

itself … because it destroys itself from within.’ Seven years later, when the

West complained about Russia’s seizure of Crimea, Putin commented acidly, ‘It’s

a good thing they at least remember that there exists such a thing as

international law – better late than never!’

A poll carried out in

2018 found that two-thirds of those asked regretted the collapse of the Soviet Union.* It was, wrote the historian, playwright, and

novelist Svetlana Boym, ‘a restorative nostalgia that

… does not think of itself as nostalgia, but rather as truth and tradition. It

knows two main plots – the return to origins and the conspiracy.’ Putin’s

approach claimed to be more nuanced. ‘Whoever does not miss the Soviet Union

has no heart,’ he wrote in 2010. ‘Whoever wants it back has no brain.’ It was a

formula that allowed a dubious past to be utilized without questioning its true

character.

When a Russian

fighter in the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic in eastern Ukraine was asked

what he was fighting for, he instinctively reached for the memory myth that

Putin and others had done much to create. ‘We need to rebuild the country,’ he

told the Guardian’s Shaun Walker. ‘The Soviet Union, the Russian Empire, it

doesn’t matter what you call it. I want a Russian idea for the Russian people;

I don’t want the Americans to teach us how to live. I want a strong country, one you can be proud of. I want life to have some

meaning again.’

The practice of

defining oneself in opposition to an external enemy was common to both sides.

James Clapper, a

former director of national intelligence, drew on the preposterous excesses of

the McCarthy era when he declared in 2017 that ‘Russians are almost genetically

driven to co-opt, penetrate, gain favor. It’s in their genes to be opposed, diametrically

opposed, to the United States and western democracies.’

The Kremlin was

convinced – and told the Russian people – that the unrest in Ukraine, Georgia

and elsewhere that occurred throughout the 2010s was stoked by the CIA. Whether

the distortion of memory by the new Cold Warriors stemmed from conviction or

was the result of deliberate role-playing,* its

real-world consequences were the same. Putin no longer pretended that his

Russia was a liberal democracy. He painted the West as corrupt, with bogus

elections and no freedom of speech, a stark contrast to the moral righteousness

of his homeland. He based his legitimacy and his international swagger on

confronting the decadent ‘other’, and it made him very popular. A Russian

journalist, Mikhail Zygar, wrote that ‘Putin has

restored a sense of pride.

Putin was vaunting

Russian military strength in order to dissuade the

Americans from pursuing their destabilizing missile defense plans. The logic of

the man in the White House was less easy to discern. Donald Trump began his

presidency with declarations of awed admiration for nuclear weapons and the

destructive power they would put at his disposal. In the final Republican

candidate debate in December 2015, he was asked what his nuclear priorities

would be as president. ‘For me,’ Trump replied, ‘nuclear – just the power, the

devastation – is very important to me.’ During the election campaign of the

following year, he seemed to endorse the premise of Nixon’s ‘madman theory’,

telling an interviewer, ‘I’m never going to rule anything out.

Even if I wasn’t, I wouldn’t want to tell you that, because at a minimum, I

want them to think maybe we would use [nuclear weapons], OK?’ As Trump’s

presidency ended in January 2021, after a disastrous riot that saw the Capitol

building overrun by his supporters, the madman theory seemed perilously close

to reality, with house speaker, Nancy Pelosi, calling General Mark Milley, the

chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, ‘to discuss available precautions for

preventing an unstable president from initiating military hostilities or

accessing the launch codes and ordering a nuclear strike’. The unpredictability

of the man in the White House made it harder – and all the

more crucial – for each side correctly to read the signals coming from

the other. Rear Admiral John Gower, a former head of the British Ministry of Defence’s nuclear weapons policy team, was tasked with

examining the psychology of how East and West project their military intentions

to each other.

Neither side will

make informed decisions under these conditions. The risk of unleashing a war

from which the globe will not recover remains real, long after the Cold War is

supposed to have ended.

After returning to

Russia, Putin rose to become head of the Federal Security Service (FSB) - the

main successor to the KGB. He became Russian president in 2000.

A Russian serviceman

fires a Verba air defense system during an exercise at Opuk

range in Crimea;

The nostalgia people

feel for the Soviet Union is less to do with military

power and confronting the West than with the sense of security they had about

their lives. They missed a time when the price of ice creams

and sausages didn’t change. The 1990s, by contrast, brought runaway inflation,

and the pension reforms of 2018 heaped added misery on the already straitened

lives of elderly people. In the USSR, people felt they lived in a superpower,

in which their lives would not be upended from one day to the next (except, of

course, that they eventually were). ‘Nostalgiya po SSSR’

(‘Nostalgia for the USSR’).

The Cold War was a

time of tension, fear, and danger, but because it ended in ‘victory’ for the

West, it came to be viewed with nostalgia. Whereby the next

'cold war' might be of a different character.

While NATO

warns Russia over Ukraine's military build-up Russia is planning to go

ahead with deploying a new paratroop regiment on annexed Crimea next month and

criticized a British agreement to boost Ukraine's navy. Russia's military

said it would establish the new regiment on the peninsula Russia annexed

from Ukraine in 2014,

completing a reshuffle of forces touted by Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu in

March, the Interfax news agency reported.

At the same time, Moscow

voiced its objections to a framework agreement under which Ukraine will use

British financing to enhance its naval capabilities, allowing it to buy

missiles and build missile ships and a navy base on the Sea of

Azov. "We see this fact as the latest practical evidence of

increasing British military activity in the states bordering Russia, in

particular Ukraine," Russia's Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria

Zakharova told a weekly briefing.

Whereby it should

once more be emphasized that there are different versions about when the Cold

War would have started, there is the Western version which we have mentioned

above, yet this contrasts with the version that is thought in Russia including

as thought to all Russian diplomats and graduates of the Foreign

Intelligence Academy of the SVR (Foreign Intelligence Service).

The story they are

thought is that the Cold War started following a coup orchestrated by the

US and the UK to topple the Lenin regime and kill Lenin. This idea was started

by Secretary of State Lansing when he told

President Wilson on 10 Dec. 1917 that the only hope for Russia lay in

setting up a “military dictatorship.” Lansing’s idea was to choose one man and

make him the boss of Russia on the side of America and the Allies. And in turn,

David R. Francis, the American ambassador to Russia, asked Washington for 100,000 troops to take

Petrograd and Moscow to support the coup against Lenin.

To this comes as we

will show in our upcoming new case study about the First World War

that The First World War had profound global importance. It led to the

collapse of four of the world’s most powerful empires, namely those of Russia,

Austria-Hungary, Germany, and the Ottomans. It almost bankrupted the French and

British empires. It occasioned the Russian revolutions of 1917 and brought the

Soviet Union into being. It confirmed that the United States and Japan had

become powerful industrial and imperial states.

The war was carried

on the winds of global commerce, finance, and information exchange and was won

by those who most effectively mobilized the available human and material

resources. As a result, neutral and belligerent civilians were both victims and

instruments of this total global war.

Putin himself is a

graduate of the Foreign Intelligence Academy of the SVR (Foreign Intelligence

Service). It started to show some of his cynicism by insisting that

Russians who point out human rights violations in their country constitute a

fifth column serving hostile powers. Any nonprofit organization that receives

donations from sources outside Russia and engages in “political activity” has been

legally required since

2012 to identify itself as a “foreign agent” - a term equivalent in Russian to “foreign spy.”

This toxic label must appear on every publication, every video, every website,

and public event sponsored by such organizations. The Russian chief

prosecutor claims that because Memorial failed to include the

“foreign agent” label on certain pages of its website and on sure of its

publications (including some that were produced before it was branded a

“foreign agent”), the organization should be liquidated. In addition,

Memorial is charged with “justifying terrorism and extremism”

because some of the more than 400 individuals it lists as current “political

prisoners” - among them the jailed anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny - are considered by the Kremlin to have engaged

in such activity.

Memorial has a tone

to tell the sober, carefully documented truth to the Russian public. Sakhaargueargued that human rights, specifically free

speech and the free flow of information, were vital preconditions of good

governance. Only policies based on “deep analysis of facts, theories, and

views, presupposing unprejudiced, fearless, open discussion and conclusions”

could secure a society’s interests in the long run. Natalia Solzhenitsyn

agrees. The widow of the acclaimed writer, Gulag survivor, and Nobel laureate

Alexander Solzhenitsyn has declared that “the closure of Memorial will cause direct

and severe damage to both society and the state.” Russian journalist Dmitri

Muratov, this year’s co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, says that Memorial is “not an enemy of the people, it

is a friend of the people,” the “most important antidote against repressions.”

When he first came to

power, Putin appeared to share these sentiments. “There should always be people

who criticize the authorities,” he told National Public Radio in 2001. “At the end of

the day, it is good for the authorities because what these people are trying to

do is casting light on a problem from a perspective that the authorities

themselves may fail to notice.” He continues to talk like this, including at

the dedication in 2017 of “The Wall of Grief,” a national monument to the

victims of Soviet terror. Under Putin, public monuments to both Sakharov and

Solzhenitsyn have been erected. But these and similar gestures have become part

of a peculiar “hybrid warfare” strategy, directed at Russian society rather than

the West. Even as Putin pays public lip service to the victims of Soviet

repression, his government is dismantling all genuinely independent sources of authority within

Russia. In Memorial’s case, this involves the Orwellian tactic of invoking the

battle against terrorism to prosecute an organization dedicated to documenting

Soviet state-sponsored terror and making sure nothing as it recurs.

How is it that an

association formed by and for the descendants of the roughly 18

million Soviet citizens sent

to Stalin’s Gulag - several million of whom never returned - gets stigmatized

as a “foreign agent”? “We are not agents of anyone,” Memorial’s executive

director, Yelena Zhemkova, announced at a recent news conference. “We ourselves

decide what and how to work.” In Putin’s Russia, that ethos is now an

endangered species.

For updates click homepage here