By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Cryptocurrency-Based Crimes

Once the poster child

for responsibility in the cryptocurrency sector, Sam Bankman-Fried was

sentenced to 25 years in jail on Thursday (March 28, 2024) following his

conviction in November in what prosecutors called one of the biggest financial

fraud cases in history.

US prosecutors were

seeking a prison term of between 40 to 50 years, after a jury found him guilty

on seven fraud and conspiracy counts contributing to the downfall of his FTX

company, as seen below, once a leading crypto exchange.

Sam Bankman-Fried,

known in the crypto community as "S.B.F.," founded the collapsed FTX

exchange in 2019, after launching the crypto hedge fund Alameda Research in

2017. Before his involvement in the cryptocurrency sector, he worked as a

trader on Wall Street. At his peak, Bankman-Fried held a fortune of $26 billion

(€24 billion).

Most people (while

knowing there was a phenomenon called cryptocurrency of which anywhere

also aware it was used to make underhand payments. Then more recently,

cryptocurrency also became USD as an investment tool by people who

thought cryptocurrency would increasingly become a legitimate currency with

even cryptocurrency vending machines that showed up in grocery stores.

What brought our

attention to Sam Bankman-Fried’s case was when on 22 December 22,

Damien Williams, the US attorney for the Southern District of New York,

announced that Bankman-Fried's former colleague and onetime girlfriend,

Caroline Ellison, had pleaded guilty to seven criminal charges and was now

cooperating with the prosecutors.

Ellison's agreement

means she is waiving any defenses to charges against her. However, she'll very

likely serve nowhere near the maximum sentence of 110 years in prison for these

charges because of her cooperation.

As part of the deal,

Ellison must hand over documents, records, and evidence to prosecutors. She'll

be required to testify to a grand jury or at court trials when requested.

Ellison has also agreed to pay restitution at an amount to be determined by the

courts.

That is until the widely

aired arrest of Sam Bankman-Fried, who, as soon he set foot in the US was

allowed to go home and live with his parents..

But people didn't

seem to get the more significant part of the story.

Prosecutors Say FTX Was Engaged in a ‘Massive,

Yearslong Fraud’ A indictment unsealed on Tuesday and a complaint by the S.E.C.

describe years of wrongdoing in Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto empire.

What To Know About The Case Against Sam Bankman-Fried

After the demise of his FIX crypto empire in November, Sam Bankman-

Fried portrayed himself as a hapless but well-intentioned chief executive who

made a series of calamitous mistakes, but never knowingly committed fraud. But

a day after his arrest in the Bahamas, the US Securities and Exchange

Commission, Department of Justice and Commodity Futures Trading Commission

filed civil and criminal charges against Bankman-Fried, including that he had

orchestrated a scheme to bilk equity investors out of more than $1.8 billion.

The next week, prosecutors announced that two members of his inner circle had

pleaded guilty to fraud charges.

1. What was FTX?

It had grown into a sprawling crypto enterprise, so much so that more

than 100 entities were included when FTX filed for bankruptcy. But at its heart

there were two organizations that mattered most: Alameda Research, the trading

venture that Bankman-Fried co-founded in 2017, and FTX Trading Ltd., a crypto

exchange based in the Bahamas and founded in 2019. All told, he raised more

than $1.8 billion from equity investors, the SEC said.

2. How did it grow so big?

Alameda initially made profits by applying traditional techniques of

arbitrage to the Bitcoin market. Bankman-Fried and co-founder Gary Wang found

ways to buy the world's biggest cryptocurrency on Asian exchanges where it was

selling for slightly less, and sell it on exchanges where it was selling for

slightly more, pocketing the difference. Bankman-Fried had previously been a

trader at Jane Street, a mainstream hedge fund. When he founded FTX, he

promoted it as a platform for financially sophisticated traders and touted its

automated risk management engine to the US Congress as superior to those used

by traditional market makers. At its peak in early 2022, FTX was valued at S32

billion by its equity investors.

3. How did it get into trouble?

According to the SEC, Bankman-Fried had “from the start” improperly

diverted assets that customers had deposited with FTX for use by Alameda to

fund its trading positions and venture investments, as well as personally make

“lavish real estate purchases and large political donations,” He and Wang

borrowed more than $546 million from Alameda to buy a nearly 8% stake in

Robinhood Markets Inc., according to court papers. As the broader crypto market

declined in value through 2022, other lenders began to seek repayment from

Alameda. Even though FTX had allegedly already given Alameda billions of

dollars in customer funds, Bankman-Fried began to give Alameda even more

4. What led to its collapse?

FTX issued its own token known as FTT. Alameda had begun using FTT,

along with tokens issued by entities that FTX either owned or invested in, as

collateral for its borrowing activities, while also using FTX customer funds to

trade with. But FTT isn't backed by substantial reserves of assets. That meant

its value was tied closelv to the fortunes of FTX

itself, making it worthless as collateral if FTX or Alameda ran into trouble

and urgently needed funds. Wien questions were raised about FTT by the chief

executive of rival exchange Binance, weak oversight

and risk management at FTX compounded the problem. As clients began to withdraw

funds from FTX, it didn't know where all its pots of money were or how much of

its assets it could liquidate in a hurry, and so struggled to honor requests. That

fed into customer panic, and accelerated their rush for the exit.

5. What did Bankman-Fried say?

Bankman-Fried argued that FTX's funding problems were limited to FTX International

Ltd., the larger entity that grouped its businesses outside of the US including

Alameda and about 100 other units. FTX US was still solvent, he said in

prepared remarks for US lawmakers prior to his Dec. 12 arrest. When the extent

of the collapse became clear, Bankman-Fried also blamed himself for what he

said was a series of accounting errors caused by poor risk management. He said

that Alameda's investments had been hit hard by the broader crypto meltdown,

and that when FTX called in loans it had extended to Alameda, the trading

outfit couldn't meet those requests. He added that he wasn’t aware that Alameda

was so heavily exposed to FTX.

6. Do regulators buy that?

No. According to SEC Chair Gary Gensler, Bankman-Fried built a

"house of cards on a foundation of deception while telling investors that

it was one of the safest buildings in crypto.” FTX’s own terms of service

stated that ownership of assets deposited on its platform remained with

customers, so it was not allowed to use them elsewhere in the group as

collateral to raise funds for other investments — particularly as FTX was not a

regulated bank. Additionally, as the majority owner of Alameda, Bankman-Fried may

have had more insight into the state of its affairs than he is letting on. The

SEC alleged that Bankman-Fried personally directed that FTX’s “risk engine” not

apply to Alameda — in effect giving what the SEC called an unlimited line of

credit funded by FTX customers — and hid the extent of the ties between the two

entities from investors.

7. What specific charges does Bankman-Fried face?

Bankman-Fried was charged in a Manhattan court with eight criminal

counts, including conspiracy and wire fraud. He’s also being sued by the SEC

and the CFTC for misleading investors. One of those eight criminal counts

includes violating campaign finance laws, alleging that the former billionaire

conspired with other unnamed individuals to use corporate money and shadow

donors starting in 2020 to contribute to political campaigns. FTX customers

were suing in a bankruptcy court to try to recover some of the billions lost in

the meltdown. After initially resisting extradition, Bankman-Fried was returned

to the US and was released on a $250 million bail package. Just before his

return, Manhattan US Attorney Damian Williams announced that two of

Bankman-Fried's closest associates, Wang and former Alameda Chief Executive

Officer Caroline Ellison, had pleaded guilty to fraud and were cooperating with

the prosecution.

8. What have they admitted to?

At a court hearing on Dec. 19, Ellison said she and Bankman-Fried

knowingly misled lenders about how much Alameda was borrowing from FTX. “I knew

that it was wrong,” she said, according to a transcript of the hearing. In his

own plea hearing, Wang, who had been FTX’s chief technology officer, said he

was "directed” to make changes to the FTX platform's code that he knew

would give Alameda special privileges, and that misrepresentations were being

made to customers and investors.

9. What has been the

reaction in the world of crypto?

Bankman-Fried’s

assertions have been met with little sympathy by his former peers, who are

worried that the string of bankruptcies triggered by the FTX collapse could

crush the crypto markets for years to come (if not permanently). Some have

pointed out that a weakness in the “bad luck” argument is that FTX doesn’t

appear to have performed any stress tests for a bank-run-style scenario. The

company sold itself as a benchmark of stability in a volatile industry, and

Bankman-Fried frequently and loudly said he was eager for FTX to be regulated.

But in the end, tokens it either owned or invested in — such as the FTT token

and another called Serum — crumbled to dust.

Overall, 2022 was a

brutal year for digital assets, as rising interest rates and high-profile

bankruptcies helped feed a broad and deep selloff in the market.

In 2022, the Federal

Reserve aggressively raised interest rates to tame soaring inflation, hiking

from near-zero in March to around 4.5% nine months later.

When interest rates

rise, savings accounts offer higher yields – meaning that holding cash becomes

more attractive than investing in assets like stocks, real estate, and

cryptocurrencies.

Digital asset prices

started tumbling in January as investors began to worry about the Fed

taking a stricter stance on inflation. That month alone, bitcoin slumped 19%, and Ethereum tumbled 29%.

So where people

like Sam Bankman-Fried simple innocent victims of the Federal

Reserve, aggressively raised interest rates?

A closer look

at Cryptocurrency-based crime tells us a different story.

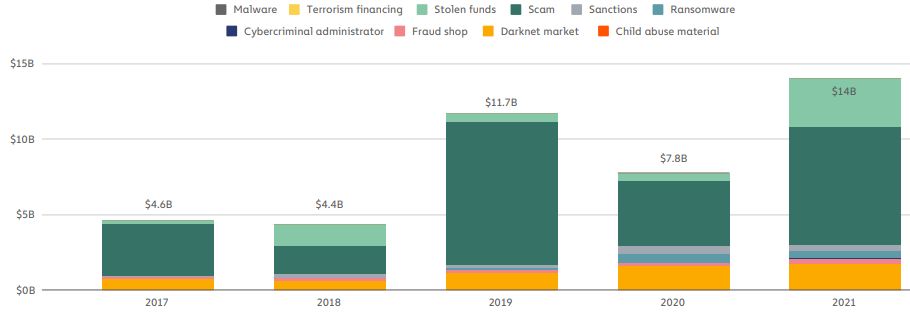

Cryptocurrency-based

crime hit a new all-time high in 2021, with illicit addresses receiving $14

billion over the year, up from $7.8 billion in 2020. See here an example

of cryptocurrency value received by illicit addresses:

But those numbers

don’t tell the full story. Cryptocurrency usage is growing faster than ever

before. Across all cryptocurrencies tracked by Chainalysis,

total transaction volume grew to $15.8 trillion in 2021, up 567% from 2020’s

totals. Given that roaring adoption, it’s no surprise that more cybercriminals

are using cryptocurrency. But the fact that the increase in illicit transaction

volume was just 79% — nearly an order of magnitude lower than overall adoption

— might be the biggest surprise of all.

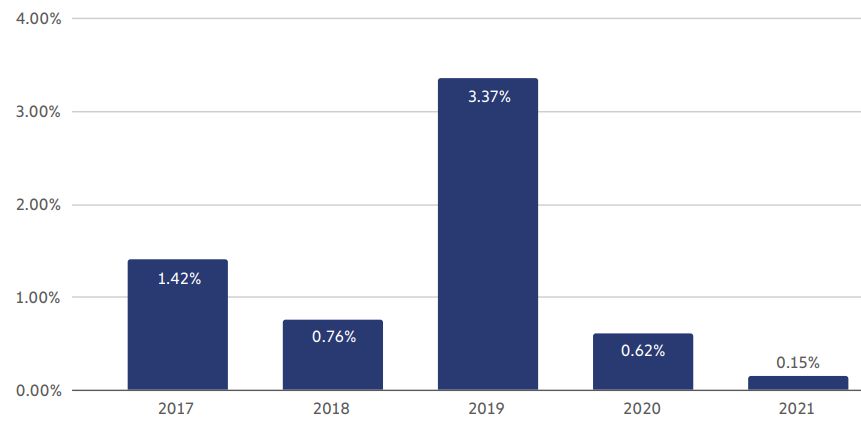

Illicit share of all cryptocurrency transaction

volume:

Transactions

involving illicit addresses represented just 0.15% of cryptocurrency

transaction volume in 2021 despite the raw value of criminal transaction volume

reaching its highest level ever. As always, we must caveat this figure and say

that it will likely rise as Chainalysis identifies

more addresses associated with illicit activity and incorporates their

transaction activity into our historical volumes. For instance, we found in our

last Crypto Crime Report that 0.34% of 2020’s cryptocurrency transaction volume

was associated with illicit activity — we’ve now raised that figure to 0.62%.

Still, the yearly trends suggest that except for 2019 — an extreme outlier year

for cryptocurrency-based crime primarily due to the PlusToken

Ponzi scheme — crime is becoming a smaller and smaller part of the

cryptocurrency ecosystem. Law enforcement’s ability to combat

cryptocurrency-based crime is also evolving. We’ve seen several examples of

this throughout 2021, from the CFTC filing charges against several investment

scams, the FBI’s takedown of the prolific REvil ransomware strain, and OFAC’s

sanctioning of Suex and Chatex,

two Russia-based cryptocurrency services heavily involved in money laundering.

However, we also have

to balance the positives of the growth of legal cryptocurrency usage with the

understanding that $14 billion worth of illicit activity represents a

significant problem. Criminal abuse of cryptocurrency impedes continued

adoption, heightens the likelihood of restrictions being imposed by

governments, and, worst of all, victimizes innocent people worldwide. In this

report, we’ll explain exactly how and where cryptocurrency-based crime

increased, dive into the latest trends amongst different types of

cybercriminals, and tell you how cryptocurrency businesses and law enforcement

agencies worldwide are responding. But first, let’s look at some key trends in

cryptocurrency-based crime.

The DeFi Scam

The crypto exchange’s

founder was throwing his weight behind regulation that would have helped his

bourse while undermining decentralized finance.

FTX’s

Sudden Unraveling May Allow Defi To Grow

A decentralized

finance (DeFi) system allows people to create financial products or “smart

contracts” that execute actions automatically on the blockchain – without any

bank, brokerage, exchange, or corporation acting as an intermediary. This

freedom has unleashed great experimentation in creating novel uses for DeFi –

such as auctioning off non-fungible (unique) tokens that have famously fetched

millions. But there are scores of other more day-to-day uses, as we’ll explore.

At the end of July

2021, the market capital for DeFi products was hovering near $80 billion. While

that was down from its May peak of more than $89 billion, pundits expect the

figure to rise in the coming year as DeFi projects mature, and as the cryptocurrency

industry makes progress on its highly public goal of lessening its

environmental impact.

Reality again paints a different picture.

Two categories stand

out for their growth: stolen funds and, to a lesser degree, scams. DeFi is a

big part of the story for both.

Let’s start with

scams. Scamming revenue rose 82% in 2021 to $7.8 billion worth of

cryptocurrency stolen from victims. Over $2.8 billion of this total — which is

nearly equal to the increase over 2020’s real — came from rug pulls, a

relatively new scam type in which developers build what appear to be legitimate

cryptocurrency projects — meaning they do more than set up wallets to receive

cryptocurrency for, say, fraudulent investing opportunities — before taking

investors’ money and disappearing. Please remember that these figures for rug

pull losses represent only the value of investors’ funds stolen and not losses

from the DeFi tokens’ subsequent loss of value following a rug pull.

We should note that

roughly 90% of the total value lost to rug pulls in 2021 can be attributed to

one fraudulent centralized exchange, Thodex, whose

CEO disappeared soon after the exchange halted users’ ability to withdraw

funds. However, every other rug pull tracked by Chainalysis

in 2021 involved DeFi projects. In nearly all of these cases, developers have

tricked investors into purchasing tokens associated with a DeFi project before

draining the tools provided by those investors, sending the token’s value to

zero in the process.

decentralized tokens

like Shiba Inu have many excited to speculate on DeFi tokens. At the same time,

it’s straightforward for those with the right technical skills to create new

DeFi tokens and get them listed on exchanges, even without a code audit. A code

audit is a process by which a third-party firm or listing exchange analyzes the

code of the smart contract behind a new token or other DeFi project. It

publicly confirms that the contract’s governance rules are ironclad and contain

no mechanisms to allow the developers to make off with investors’ funds. Many

investors could have avoided losing funds to rug pulls if they’d stuck to DeFi

projects that have undergone a code audit – or if DEXes

required code audits before listing tokens.

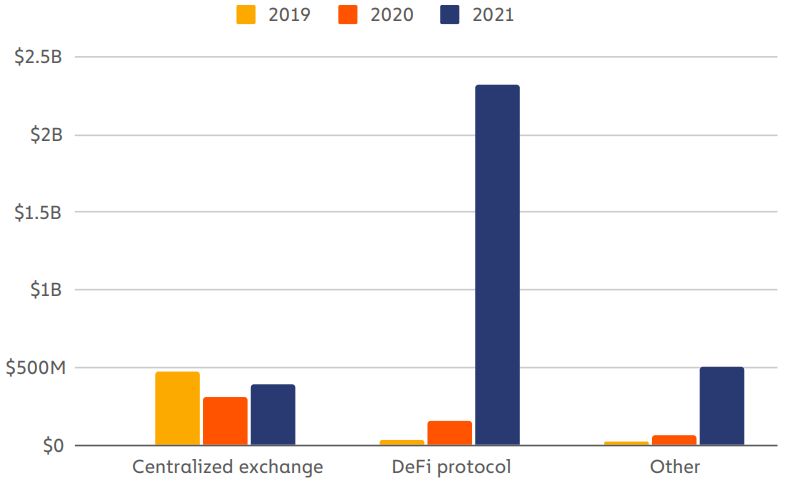

Cryptocurrency theft

grew even more, with roughly $3.2 billion worth of cryptocurrency stolen in

2021 — a 516% increase compared to 2020. Roughly $2.2 billion of those funds —

72% of the 2021 total — were stolen from DeFi protocols. The increase in DeFi-related

thefts represents the acceleration of a trend we identified in last year’s

Crypto Crime report.

Annual total cryptocurrency was stolen by victim type

As we have seen in

the above-described Sam Bankman-Fried In case 2020, just under $162

million worth of cryptocurrency was stolen from Defi platforms, which was 31%

of the year’s total amount stolen. That alone represented a 335% increase over

the total stolen from Defi platforms in 2019. In 2021, that figure rose another

1,330%. In other words, as DeFi has continued to grow, so too has its issue

with stolen funds. As we’ll explore in more detail later in the report, most

instances of theft from DeFi protocols can be traced back to errors in the

smart contract code governing those protocols, which hackers exploit to steal

funds, similar to the errors that allow rug pulls to occur.

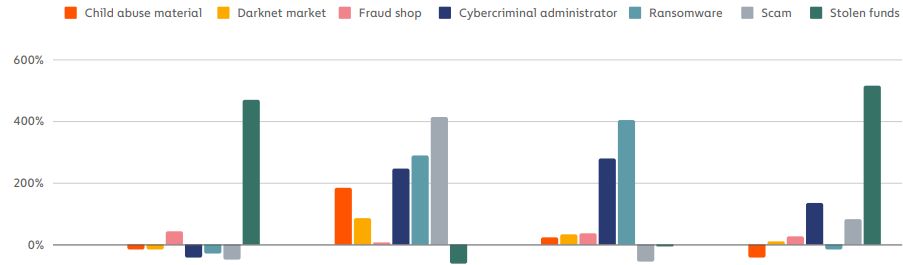

We’ve also seen

significant growth in the usage of DeFi protocols for laundering illicit funds,

a practice we saw scattered examples of in 2020 and that became more prevalent

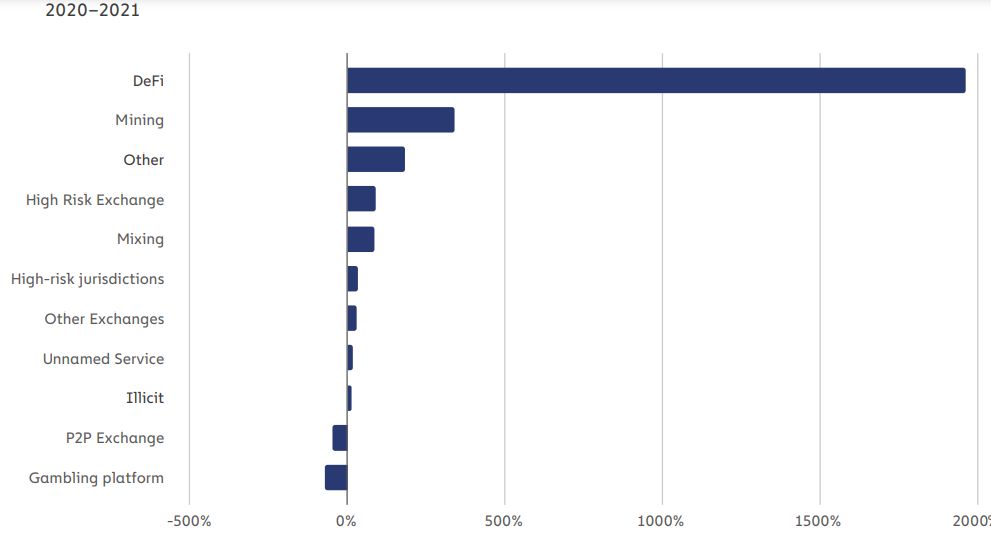

in 2021. Check out the graph below, which looks at the growth in illicit funds received

by different types of services in 2021 compared to 2020. Year-over-year

percentage growth in value received by service from illicit addresses 2020–2021

DeFi protocols saw the most growth by far in usage for money laundering at

1,964%. DeFi is one of the most exciting areas of the wider cryptocurrency

ecosystem, presenting huge opportunities to entrepreneurs and cryptocurrency

users. But DeFi is unlikely to realize its full potential if the same

decentralization that makes it so dynamic also allows for widespread scamming

and theft. One way to combat this is better communication — both the private

and public sectors have an important role in helping investors learn how to

avoid dubious projects. In the longer term, the industry may also need to take

more drastic steps to prevent tokens associated with potentially fraudulent or

unsafe schemes from being listed on major exchanges. Illicit cryptocurrency

balances are growing. What can law enforcement do? One promising development in

the fight against cryptocurrency-related crime is the growing ability of law

enforcement to seize illicitly obtained cryptocurrency. In November DeFi Mining

Other High-Risk Exchange Mixing High-risk jurisdictions Other Exchanges Unnamed

Service Illicit P2P Exchange Gambling platform -500% 0% 500% 1000% 1500% 2000%

Year over year percentage growth in value received by service from illicit

addresses.

DeFi protocols saw the most growth by far in usage for

money laundering at 1,964%.

Illicit

cryptocurrency balances are growing. What can law enforcement do? One promising

development in the fight against cryptocurrency-related crime is the growing

ability of law enforcement to seize illicitly obtained cryptocurrency. In

November 2021, for instance, the IRS Criminal Investigations announced that it

had taken over $ 3.5 billion worth of cryptocurrency in 2021 — all from non-tax

investigations — representing 93% of all funds taken by the division during

that period. We’ve also seen several examples of successful seizures by other

agencies, including $56 million seized by the Department of Justice in a

cryptocurrency scam investigation, $2.3 million seized from the ransomware

group behind the Colonial Pipeline attack, and an undisclosed amount seized by

Israel’s National Bureau for Counter Terror Financing in a case related to

terrorism financing.

Does this raise an

interesting question: How much cryptocurrency are criminals currently holding?

It’s impossible to know for sure, but we can estimate based on the current

holdings of addresses Chainalysis has identified as

associated with illicit activity. As of early 2022, illicit addresses hold at

least $10 billion worth of cryptocurrency, with the vast majority of this held

by wallets associated with cryptocurrency theft. Addresses associated with darknet

markets and scams contribute significantly to this figure. As we’ll explore

later in this report, much of this value comes not from the initial amount

derived from criminal activity but from subsequent price increases of the

crypto assets held.

We believe it’s

important for law enforcement agencies to understand these estimates as they

build out their blockchain-based investigative capabilities, and especially as

they develop their ability to seize illicit cryptocurrency.n

Let’s make cryptocurrency safer

DeFi-related crime

and criminal cryptocurrency balances are just one area of focus for this

report. We’ll also look at the latest data and trends on other forms of

cryptocurrency based crime, including:

• The ongoing threat of ransomware

• Cryptocurrency-based money laundering

• Nation state actors’ role in cryptocurrency-based

crime

• Illicit activity in NFTs

And much more!

As cryptocurrency

grows, the public and private sectors must work together to ensure that users

can transact safely and that criminals can’t abuse these new assets. We hope

this report can contribute to that goal and equip law enforcement, regulators,

and compliance professionals with the knowledge to prevent, mitigate, and

investigate cryptocurrency-based crime more effectively.

DeFi Takes on Bigger

Role in Money Laundering But Small Group of Centralized Services Still Dominate

Cybercriminals

dealing in cryptocurrency share one common goal: Move their ill-gotten funds to

a service where they can be kept safe from the authorities and eventually

converted to cash. That’s why money laundering underpins all other forms of

cryptocurrency-based crime. If there’s no way to access the funds, there’s no

incentive to commit crimes involving cryptocurrency in the first place.

Money laundering

activity in cryptocurrency is also heavily concentrated. While billions of dollars worth of cryptocurrency moves from illicit

addresses every year, most of it ends up at a surprisingly small group of

services, many of which appear purpose-built for money laundering based on

their transaction histories. Law enforcement can strike a huge blow against

cryptocurrency-based crime and significantly hamper criminals’ ability to

access their digital assets by disrupting these services. We saw an example of

this last year, when the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets

Control (OFAC) sanctioned

two of the

worst-offending money laundering services — Suex and Chatex — for accepting funds from ransomware operators,

scammers, and other cybercriminals. But as we’ll explore below, many other

money laundering services remain active.

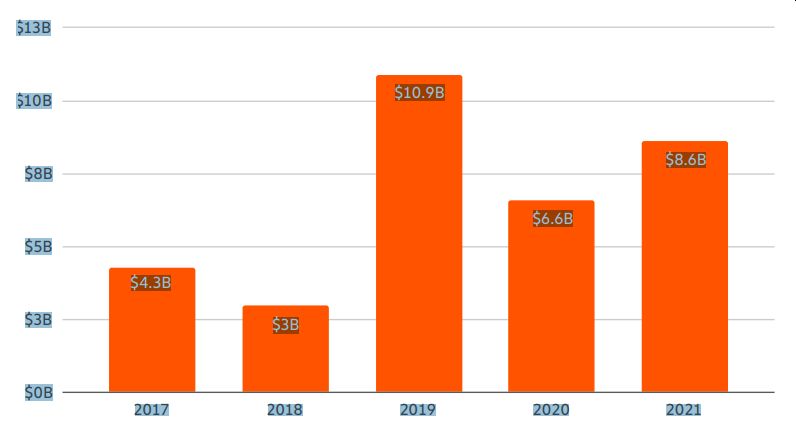

2021 cryptocurrency

money laundering activity summarized Overall, going by the amount of

cryptocurrency sent from illicit addresses to addresses hosted by services,

cybercriminals laundered $8.6 billion worth of cryptocurrency in 2021.

Total cryptocurrency value laundered by year |

2017–2021

That represents a 30%

increase in money laundering activity over 2020, though such an increase is

unsurprising given the significant growth of both legitimate and illicit

cryptocurrency activity in 2021. We also need to note that these numbers only

account for\ funds derived from “cryptocurrency-native” crime, meaning

cybercriminal activity such as darknet market sales or ransomware attacks in

which profits are virtually always derived in cryptocurrency rather than fiat

currency. It’s more challenging to measure how much fiat currency derived from

offline crime — traditional drug trafficking, for example — is converted into

cryptocurrency to be laundered. However, we know this is happening anecdotally,

and later in this section, we provide a case study showing an example of it.

Cybercriminals have laundered over $33 billion worth of cryptocurrency since

2017, with most of the time moving to centralized exchanges. For comparison,

the UN Office of

Drugs and Crime estimates that between $800 billion and $2 trillion of fiat

currency is laundered each year — as much as 5% of global GDP. For comparison,

money laundering accounted for just 0.05% of all cryptocurrency transaction

volume in 2021. We cite those numbers not to try and minimize cryptocurrency’s

crime-related issues but rather to point out that money laundering is a plague

on virtually all forms of economic value transfer, and to help law enforcement

and compliance professionals be barware of just how much money laundering

activity could theoretically move to cryptocurrency as adoption of the

technology increases. The most significant difference between fiat and

cryptocurrency-based money laundering is that, due to the inherent transparency

of blockchains, we can more easily trace how criminals move cryptocurrency

between wallets and services in their efforts to convert their funds into cash.

What kinds of cryptocurrency services do criminals rely on for this?

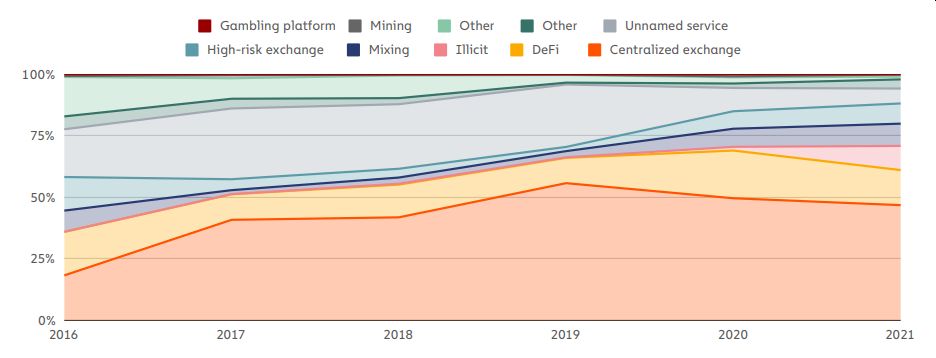

Destination of funds leaving illicit addresses |

2016–2021

For the first time

since 2018, centralized exchanges didn’t receive the majority of funds sent by

illicit addresses last year, instead taking in just 47%. Where did

cybercriminals

For the first time since

2018, centralized exchanges didn’t receive the majority of funds sent by

illicit addresses last year, instead taking in just 47%. Where did

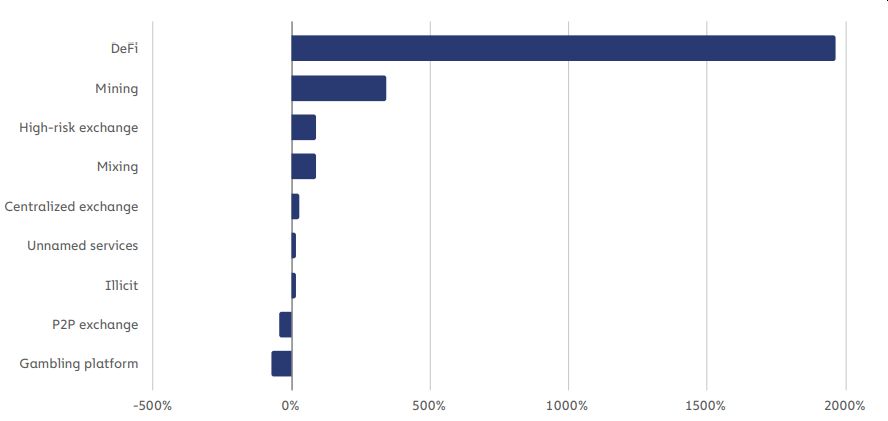

cybercriminals send funds instead? DeFi protocols make up much of the

difference. DeFi protocols received 17% of all funds sent from illicit wallets

in 2021, up from 2% the previous year. That translates to a 1,964%

year-over-year increase in total value received by DeFi protocols from criminal

addresses, reaching $900 million in 2021. Mining pools, high-risk exchanges,

and mixers also saw substantial increases in value received from illicit

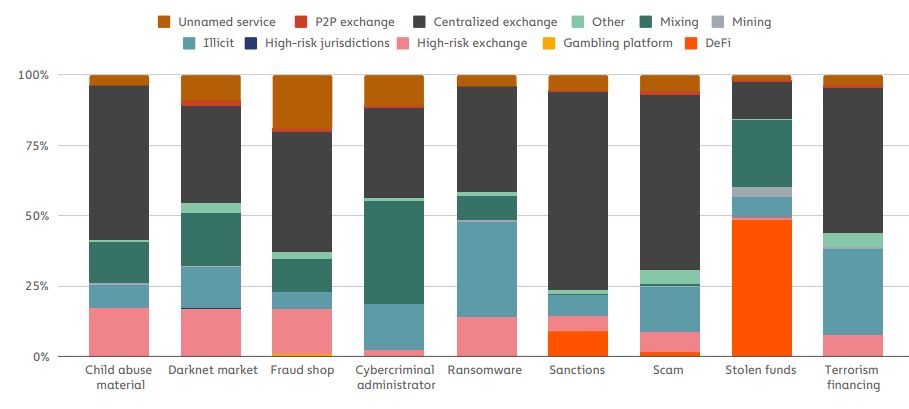

addresses. We also see patterns in which types of services different

cybercriminals use to launder cryptocurrency. DeFi Mining High-risk exchange

Mixing Centralized exchange Unnamed services Illicit P2P exchange Gambling

platform -500% 0% 500% 1000% 1500% 2000% Year over year percentage growth in

value received from illicit addresses by service category 2020–2021 Year over

year percentage growth in value received from illegal addresses by service

category | 2020–2021.

That translates to a

1,964% year-over-year increase in value received by DeFinprotocols

from illicit addresses, reaching a total of $900 million in 2021. Mining pools,

high-risk exchanges, and mixers also saw substantial increases in value

received from illicit addresses.

We also see patterns

in which types of services cybercriminals use tonlaunder

cryptocurrency.

One thing that stands

out is the difference in laundering strategies between the two highest-grossing

forms of cryptocurrency-based crime in 2021: Theft and scamming. addresses associated

with theft sent just under half of their stolen funds to DeFinplatforms

— over $750 million worth of cryptocurrency. North Korea-affiliated hackers,

responsible for $400 million cost of cryptocurrency hacks last year, used DeFi

protocols for money laundering quite a bit. This may be related to more

cryptocurrency being stolen from DeFi protocols than any other platform

previous year. We also see an actual mixer usage in the laundering of stolen

funds.

On the other hand,

scammers send most of their funds to addresses at centralized exchanges. This

may reflect scammers’ relative lack of sophistication. Hacking cryptocurrency

platforms to steal funds takes more technical expertise than carrying out most scams

we observe, so it makes sense that those cybercriminals would employ a more

advanced money laundering strategy.

We also need to

reiterate that we can’t track all money laundering activity by measuring the

value sent from known criminal addresses. As stated above, some criminals use

cryptocurrency to launder funds from offline crimes, and many illegal addresses

in use have yet to be identified. However, we can account for some of these

more obscured instances of money laundering by looking for transaction patterns

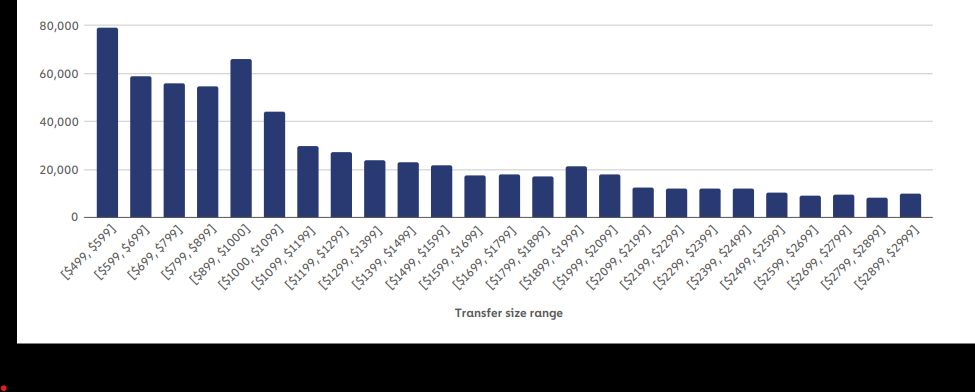

suggesting that users were trying to avoid compliance screens. For example, due

to regulations like the Travel Rule, cryptocurrency businesses in many

countries must conduct additional compliance checks, reporting, and information

sharing related to transactions above USD 1,000. As you might expect, illicit

addresses send disproportionate transfers to exchanges just below that $1,000

threshold. Number of transfers from criminal addresses to exchanges by transfer

size | 2021 Transfer size range

Number of transfers from illicit addresses to

exchanges by transfer size | 2021

Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, Part Five

For updates click hompage here