By Eric Vandenbroeck

and co-workers

When The Past Does Not Go Away

There

aren’t enough palm trees, the Soviet general thought to himself. It was July

1962, and Igor Statsenko, the 43-year-old

Ukrainian-born commander of the Red Army’s missile division, found himself

inside a helicopter, flying over central and western Cuba. Below him lay a

rugged landscape with few roads and a little forest. Seven weeks earlier, his superior—Sergei

Biryuzov, the commander of the Soviet Strategic

Missile Forces—had traveled to Cuba disguised as an agricultural expert. Biryuzov had met with the country’s prime minister, Fidel

Castro, and shared an extraordinary proposal from the Soviet Union’s leader,

Nikita Khrushchev, to station ballistic nuclear missiles on Cuban soil. Biryuzov, an artilleryman by training who knew little about

missiles, returned to the Soviet Union to tell Khrushchev that the missiles

could be safely hidden under the foliage of the island’s plentiful palm trees.

But when Statsenko, a no-nonsense professional, surveyed the Cuban

sites from the air, he realized the idea was hogwash. He and the other Soviet

military officers on the reconnaissance team immediately raised the problem

with their superiors. In the areas where the missile bases were supposed to go,

they pointed out, the palm trees stood 40 to 50 feet apart and covered only

one-sixteenth of the ground. There would be no way to hide the weapons from the

superpower 90 miles to the north.

But the news never

reached Khrushchev, who moved forward with his scheme in the belief that the

operation would remain secret until the missiles were in place. It was a

fateful delusion. In October, an American high-altitude U-2 reconnaissance

plane spotted the launch sites, and what became known as “the Cuban missile

crisis” began. For a week, U.S. President John F. Kennedy and his advisers

debated in secret how to respond. Ultimately, Kennedy chose not to launch a

preemptive attack to destroy the Soviet sites and declared a naval blockade

of Cuba to give Moscow a chance to back off. Over 13 frightening

days, the world stood on the brink of nuclear war, with Kennedy and Khrushchev

facing off “eyeball to eyeball,” in the memorable words of Secretary of

State Dean Rusk. The crisis ended when Khrushchev capitulated and withdrew

missiles from Cuba in return for Kennedy’s public promise not to invade the

island and a secret agreement to withdraw American nuclear-tipped missiles from

Turkey.

The details of the

palm tree fiasco are just some revelations in the hundreds of pages of newly

released top-secret documents about Soviet decision-making and military

planning. Some came from the archives of the Soviet Communist Party and were

declassified before the war in Ukraine; others were quietly declassified by the

Russian Ministry of Defense in May 2022, in the run-up to the sixtieth

anniversary of the Cuban missile crisis. The decision to release these

documents without redaction is just one of many paradoxes of President Vladimir

Putin’s Russia. State archives release vast evidence about the Soviet past even

as the regime cracks down on free inquiry and spreads ahistorical propaganda.

We were fortunate to obtain these documents when we did; the ongoing tightening

of screws in Russia will likely reverse recent strides in declassification.

The documents shed

new light on the most hair-raising Cold War crises, challenging many

assumptions about what motivated the Soviets’ massive operation in Cuba and why

it failed so spectacularly. During escalating tensions with another brash

leader in the Kremlin, the crisis story offers a chilling message

about the risks of brinkmanship. It also illustrates the degree to which

the difference between catastrophe and peace often comes down not to considered

strategies but to pure chance.

The evidence shows

that Khrushchev’s idea to send missiles to Cuba was a remarkably poorly

thought-through gamble whose success depended on good luck. Far from being a

bold chess move motivated by cold-blooded realpolitik, the Soviet operation

resulted from Khrushchev’s resentment of U.S. assertiveness in Europe and his

fear that Kennedy would order an invasion of Cuba, overthrowing Castro and

humiliating Moscow in the process. And far from being an impressive display of

Soviet cunning and power, the operation was plagued by a profound lack of

understanding of on-the-ground conditions in Cuba. The palm tree fiasco was

just one of many blunders the Soviets made throughout the summer and fall of

1962.

The revelations have

special resonance at a time when, once again, a leader in the Kremlin is

engaged in a risky foreign gambit, confronting the West as the specter of

nuclear war lurks in the background. As then, Russian decision-making is driven

by hubris and a sense of humiliation. Now, as then, the military brass in

Moscow is staying silent about the massive gap between the operation the leader

had in mind and the reality of its implementation.

At a

question-and-answer session in October, Putin was asked about

parallels between the current crisis and the one Moscow faced 60 years

earlier. He responded cryptically. “I cannot imagine myself in the role

of Khrushchev,” he said. “No way.” But if Putin cannot see the

similarities between Khrushchev’s predicament and the one he now faces, he

truly is an amateur historian. Russia, it seems, still has not learned the

lesson of the Cuban missile crisis: that the whims of an autocratic ruler can

lead his country into a geopolitical cul-de-sac—and the world to the edge of

calamity.

In 1962, Khrushchev

reversed course and found a way out. Putin has yet to do the same.

A Modest Proposal

“Our whole operation

was to deter the USA so they don’t attack Cuba,” Khrushchev told his

top political and military leaders on October 22, 1962, after learning from the

Soviet embassy in Washington that Kennedy was about to address the American

people. Khrushchev’s words are preserved in the detailed minutes of the meeting,

recently declassified in the Soviet Communist Party archives. The United States

had nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy. Why couldn’t the Soviet Union have

them in Cuba? He continued: “In their time, the USA did the same

thing, having encircled our country with missile bases. This deterred us.”

Khrushchev expected the United States to simply put up with Soviet deterrence,

just as he had put up with U.S. deterrence.

Khrushchev had gotten

the idea to send missiles to Cuba months earlier, in May, when he concluded

that the CIA’s failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 had been just a

trial run. He recognized that an American takeover of Cuba would seriously blow

the Soviet leader’s credibility and expose him to charges of ineptitude in

Moscow. But as the minutes of the October 22 meeting make clear, there was more

to Khrushchev’s decision-making than concerns about Cuba. Khrushchev deeply

resented what he perceived as unequal treatment by the United States. And

contrary to the conventional story, he was equally worried about China, which

he feared would exploit a defeat in Cuba to challenge his claim to leadership

of the global communist movement.

Khrushchev entrusted

the implementation of his daring idea to three top military commanders—Biryuzov, Rodion Malinovsky (the

defense minister), and Matvei Zakharov (the head of

the general staff)—and the whole operation was planned by a handful of officers

in the general staff working in utmost secrecy. One of the key newly released

documents is a formal proposal for the operation prepared by the military and

signed by Malinovsky and Zakharov. It is dated May 24, 1962—just three days

after Khrushchev broached his idea of putting missiles in Cuba at the Defense

Council, the supreme military-political body he chaired.

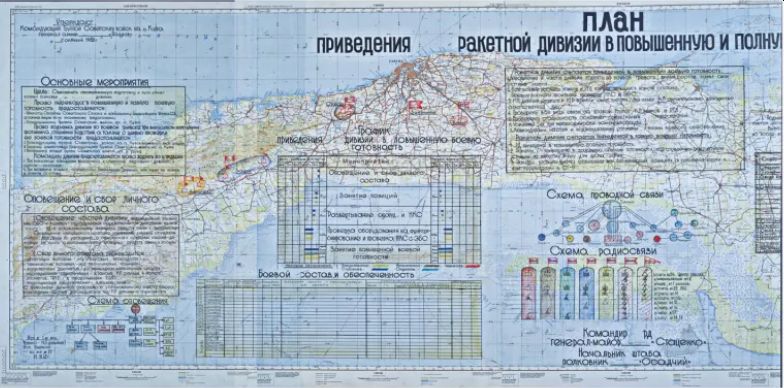

A map of Cuba with detailed instructions on readying

the Soviet missile division in the country

According to the

proposal, the Soviet army would send the 51st Missile Division to Cuba,

consisting of five regiments: all of the group’s officers and soldiers, about

8,000 men, would leave their base in western Ukraine and be permanently

stationed in Cuba. They would bring 60 ballistic missiles: 36 medium-range

R-12s and 24 intermediate-range R-14s. The R-14s were a particular challenge:

at 80 feet long and 86 metric tons, the missiles required a host of

construction engineers and technicians, as well as dozens of tracks, cranes,

bulldozers, excavators, and cement mixers to install them on launching pads in

Cuba. Many other soldiers and equipment would join the troops of the missile

division in Cuba: two antiaircraft divisions, one regiment of IL-28 bombers,

one air force squadron of MiG fighters, three regiments with helicopters and

cruise missiles, four infantry regiments with tanks, and support and logistics

troops. The list of these units filled five pages of the proposal on May 24:

44,000 men in uniform, plus 1,800 construction and engineering specialists.

Soviet generals had

never before deployed a full missile division and so many troops by sea, and

now they had to send them to another hemisphere. Unfazed, the military planners

christened the operation with the code “Anadyr,” after the Arctic river, across

the Bering Sea from Alaska—a geographical misdirection designed to confuse U.S.

intelligence.

At the top of the

proposal, Khrushchev wrote “agree” and signed his name. Some distance below is

the signatures of 15 other senior leaders. Khrushchev wanted to ensure no other

leadership members could distance themselves from it if the operation failed.

He had successfully browbeaten his colleagues into signing onto his

hare-brained scheme. A strikingly similar scene would repeat itself 60 years

later when, days before the invasion of Ukraine, Putin forced members of his

security council, one by one, to speak out loud and endorse his “special

military operation” at a televised meeting.

Operation Anadyr

On May 29, 1962, Biryuzov arrived in Cuba with a Soviet delegation and posed

as an agricultural engineer named Petrov. The Cuban leader's eyes lit up when

he conveyed Khrushchev’s proposal to Castro. Castro embraced Soviet

missiles to serve the entire socialist camp, a Cuban contribution to the

struggle against American imperialism. During this trip, Biryuzov

concluded that palm trees could camouflage the missiles.

In June, when

Khrushchev met with the military again, Aleksei Dementyev, a Soviet military adviser in Cuba summoned to

Moscow, emerged as a lonely voice of caution. As he began to say that it was impossible

to hide the missiles from the American U-2s, Malinovsky kicked his subordinate

under the table to make him shut up. The operation had already been decided; it

was too late to challenge it, much less to Khrushchev’s face. By now, there was

no stopping Anadyr. In late June, Castro sent his brother Raúl, the defense

minister, to Moscow to discuss a mutual defense agreement to legitimize Soviet

military deployments in Cuba. With Raúl, Khrushchev was full of bombast, even

promising to send a military flotilla to Cuba to demonstrate Soviet resolve in

the United States' backyard. Kennedy, he boasted, would do nothing. Yet behind

the usual bluster lay fear. Khrushchev wanted to keep Anadyr secret for as long

as possible, lest the U.S. intervene and upend his ambitious plans. And so, the

Soviet-Cuban military agreement was never published.

Top Soviet commanders

also wanted to conceal the true purpose of Operation Anadyr—even from much of

the rest of the Soviet military. The official documents, part of the recently

declassified trove, referred to the operation as an “exercise.” Thus, the

greatest gamble in nuclear history was presented to the rest of the military as

routine training. In a striking parallel, Putin’s misadventure in Ukraine was

also billed as an “exercise,” with unit-level commanders being left in the dark

until the last moment.

Operation Anadyr

began in earnest in July. On the 7th, Malinovsky reported to Khrushchev that

all the missiles and personnel were ready to leave for Cuba. The expedition was

named the Group of Soviet Forces in Cuba. Its commander was Issa Pliev, a grizzled, 59-year-old cavalry general, a veteran

of both the Russian Civil War and World War II. The same day, Khrushchev

met with him, Statsenko, and 60 other generals,

senior officers, and commanders of units as they prepared to depart. Their

mission was to fly to Cuba for reconnaissance to prepare everything for the

armada's arrival with missiles and troops in the following months. On July 12,

the group arrived in Cuba aboard an Aeroflot passenger plane. A week later, a

hundred additional officers arrived on two more flights.

The hasty journey was

rife with mishaps. The rest of Soviet officialdom botched the cover story for

the reconnaissance group: in newspapers, the passengers on the Aeroflot planes

were called “specialists in civil aviation,” even though in Cuba, they had been

billed as “specialists in agriculture.” When one flight landed in Havana, no

one greeted the passengers, so the officers poked around the airport for three

hours before finally being whisked away. Another flight ran into storms and had

to divert to Nassau, the Bahamas, where curious American tourists snapped

pictures of the Soviet plane and its passengers.

Statsenko arrived on July 12. From July 21 to 25, he and other

Soviet officers crisscrossed the island, wearing Cuban army uniforms and

accompanied by Castro’s bodyguards. They inspected the sites that had been

selected for deploying five missile regiments, all in western and central Cuba,

in keeping with Biryuzov’s optimistic report. Statsenko wasn’t just disturbed by the sparsity of palm

trees. As he later complained in a report—another recently released

document—the Soviet team lacked even basic knowledge of the conditions in Cuba.

No one provided them with briefing materials on the tropical island's

geography, climate, and economic conditions. They didn’t even have maps; those

were scheduled to arrive later by ship. Heat and humidity hit the team hard.

Castro sent a few of his staff officers to help with the inspections, but there

were no interpreters, so the reconnaissance team had to take a crash course in

elementary Spanish. What little Spanish the officers had picked up in a few

days did not get them far.

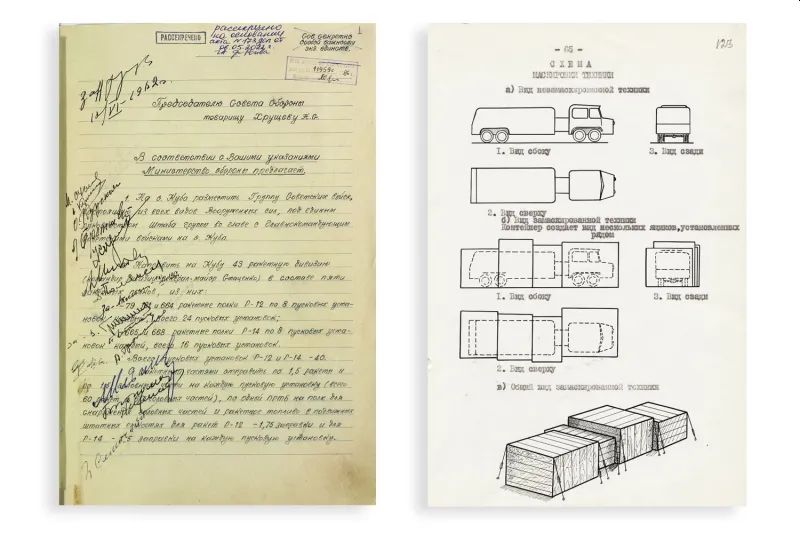

Left: The May 24

proposal to send nuclear missiles to Cuba, signed at the top by Khrushchev and

below by 15 other senior leaders; Right: The Soviet military’s

instructions on how to hide equipment on ships destined for Cuba

With the initial

missile sites hopelessly exposed, Pliev, the man in

charge, ordered the reconnaissance teams to find better locations in remote

areas protected by hills and forests. (According to Castro’s instructions, they

also had to find sites that would not require the large-scale resettlement of

peasants.) Pliev asked the general staff back in

Moscow twice if he could move some missile locations to more suitable areas.

Each time, Moscow rejected the initiative. Some new areas were rejected because

they “were in the area of international flights”—a sensible precaution to avoid

the possibility of Soviet surface-to-air missiles accidentally shooting down

civilian aircraft. But other locations were rejected because they “did not

correspond to the directive of the general staff”. In other words, the planners

in Moscow did not want to change what their superiors had already approved. In

the end, the missiles were assigned to exposed areas.

Apart from the

unexpected difficulties siting the missiles, the Soviets encountered other

surprises in Cuba. Pliev and other generals planned

to dig underground shelters for the troops, but Cuban soil proved too rocky.

Soviet electrical equipment, meanwhile, was incompatible with the Cuban

electricity supply, which operated on the North American standard of 120 volts

and 60 hertz. The Soviet planners had also forgotten to consider the weather:

hurricane season in Cuba runs from June through November, precisely when the

missiles and troops had to be deployed, and the unceasing rains impeded

transportation and construction. Soviet electronics and engines, designed for

Europe's cold and temperate climates, quickly corroded in the sweltering

humidity. The general staff sent instructions for operating and maintaining

weaponry in tropical conditions in September, well after the operation began.

“All this should have

been known before the reconnaissance work started,” Statsenko

told his superiors two months after the crisis ended, his memo dripping with

irritation. He took planners to task for knowing so little about Cuba. “The

whole operation should have been preceded at least by a minimal acquaintance

and study—by those who were supposed to carry out the task—of the economic

capabilities of the state, the local geographic conditions, and the military

and political situation in the country.” He did not dare mention Biryuzov by name, but at any rate, it was clear that the

real culprit was Khrushchev, who had left his military no time to prepare.

Precious Cargo

For all the fumbles,

Anadyr was a considerable logistical accomplishment. The scale of the shipments

was enormous, as the newly declassified documents detail. Hundreds of trains

brought troops and missiles to eight Soviet departure ports, including

Sevastopol in Crimea, Baltiysk in Kaliningrad, and

Liepaja in Latvia. Nikolayev—today, the Ukrainian city of Mykolayiv—on

the Black Sea served as the main shipping hub for the missiles because of its

giant port facilities and railroad connections. Since the port’s cranes were

too small to load the bigger rockets, a floating 100-ton crane was brought in

to do the job. The loading proceeded at night and usually took two or three

days per missile. Everything was done for the first time, and Soviet engineers

had to solve countless problems on the fly. They figured out how to strap

missiles inside ships normally transporting grain or cement and safely store

liquid rocket fuel inside the hold. Two hundred and fifty-six railroad cars

delivered 3,810 metric tons of munitions. Some 8,000 trucks and cars, 500

trailers, and 100 tractors were sent, along with 31,000 metric tons of fuel for

cars, aircraft, ships, and missiles. The military dispatched 24,500 metric tons

of food. The Soviets planned to stay in Cuba for a long time.

From July to October,

the armada of 85 ships ferried men and supplies from the Black Sea, through the

Mediterranean, and across the Atlantic Ocean. The ships’ crews could see that

their vessels were not going unnoticed. As declassified reports from captains,

military officers, and KGB officers reveal, planes—some

from NATO countries, others unidentified—flew over the ships more

than 50 times. According to a declassified Soviet report, one of the planes

even crashed into the sea. The U.S. Navy followed some of the ships. Each

Soviet vessel was armed with two double-barreled heavy machine guns. Secret

instructions from Moscow allowed the troops on board to fire if their ship was

about to be boarded; if it was on the verge of being seized, they were to move

all men to rafts, destroy all documents, and sink the ship with its cargo. But

a potential emergency was just one of many worries. In relative comfort, some

troops traveled by passenger ship, but most sailed on merchant ships that the

Soviets had assigned to the operation. These troops faced an ordeal: they

huddled in cramped cargo holds that they shared with equipment, metal parts,

and lumber. Often, they fell sick. Some of the men died en

route and were buried at sea.

But the ships got

lucky and reached Cuba without incident. On September 9, the first six R-12

missiles, stowed inside the cargo ship Omsk, arrived in the port of

Casilda on Cuba’s southern coast. Others arrived

later in Mariel, just west of Havana. The missiles were offloaded secretly at

night, between 12 and 5 am. The construction workers who were supposed to

build pads for the heavier R-14 missiles had not yet arrived, so the soldiers

had to do all the work. Soviet military boats and scuba divers secured the

nautical zone. Everyone changed into Cuban uniforms. Speaking Russian,

according to the instructions of the general staff, was “categorically

forbidden.”

Three hundred Cuban

soldiers and even some “specially tested and selected fishermen” protected the

ports where the missiles would be brought in. The Cuban army and police

cordoned the roads and even staged fake car accidents along the route from the

port to the missile sites to keep the local population away. A spot west of

Havana that would serve as a launch site for R-14 missiles was impossible to

conceal, so it was presented to the Cuban public as “the construction site for

a Cuban military training center.” Very few Cubans knew about the missiles.

Only 14 Cuban officials had a complete view of the operation: Fidel, Raúl, the

Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara (then one of Fidel’s top advisers), Pedro

Luis Rodríguez (the head of Cuban military intelligence), and ten other senior

military officers.

There was now about

42,000 Soviet military personnel on Cuban soil. Those from Statsenko’s

missile division focused on constructing launching pads for R-12 missiles.

Others manned the bombers, surface-to-air missiles, fighter jets, and other

weaponry that Moscow had sent to the island. Once again, however, tropical

conditions slowed progress. Rain, humidity, and mosquitoes descended on the

arriving regiments. Soldiers slept in soaked tents. Temperatures exceeded 100

Fahrenheit. The camouflage remained an unsolvable problem: among the sparse

palm trees, the tents, like the missiles, were impossible to conceal.

Commanders draped the equipment in camouflage nets, the new documents reveal,

but the nets' color matched Russia's green foliage and stood out sharply

against the sun-scorched Cuban landscape.

The Soviet general

staff wanted the R-12 launch pads completed by November 1. From September

through the first half of October, the crews worked overtime to meet this

deadline, but again they were delayed by snafus. For example, the construction

crews supposed to install R-14 missiles spent a month in Cuba waiting for their

equipment to arrive. Some of the parts for the R-12 launchers were weeks late.

By mid-October, all of the missile sites were still being prepared. The one

closest to completion—the R-12 site near Calabazar de

Sagua, in central Cuba—was plagued by communications

problems, with no reliable radio link between it and the headquarters in

Havana. And then came October 14.

Caught Red-Handed

That morning, an

American U-2 spy plane, flying at 72,500 feet and equipped with a large-format

camera, passed over some of the construction sites. Two days later, the

photographs were on Kennedy’s desk.

In retrospect, it is

remarkable that it took so long for the Americans to discover the missiles,

given the extent of Soviet blunders in Cuba. Luck played a large role. The

storms that hindered the Soviet troops protected them from American snooping

since the dense cloud cover prevented aerial photography. And as it happened,

the CIA made a blunder of its own. Although the agency had detected the

arrival of Soviet antiaircraft weaponry in late August, it failed to draw the

obvious conclusion as to what the Soviet forces were so keen to protect,

concluding instead that the weapons were merely for Cuba’s conventional

defense, despite the suspicions of CIA Director John McCone.

For several days,

Kennedy deliberated with his top advisers about responding to what he viewed as

a blatant act of provocation. Many in the group, known as EXCOMM, favored an

all-out attack on Cuba to obliterate the Soviet bases. Kennedy instead opted

for a more cautious response: a naval blockade, or “quarantine,” of Cuba. His

caution was warranted, for no one could guarantee that all the missiles would

be wiped out.

This caution stemmed

partly from another source of uncertainty: whether any of the missiles were

ready. As the newly declassified documents reveal, only on October 20 did the

first site—one with eight R-12 launchers—become operational. By October 25, two

more sites were readied, although again in less-than-ideal circumstances: the

rockets had to share fueling equipment, and the Soviets had to cannibalize

personnel from regiments originally intended to operate the R-14s. By nightfall

of October 27, all 24 launchers for the R-12s, eight per regiment, were ready.

A CIA reference photograph of Soviet medium-range

ballistic missiles in Red Square, Moscow

Or rather, almost

ready. The storage facility for the R-12 nuclear warheads was located at a

considerable distance from the missile sites: 70 miles from one regiment, 90

miles from another, and 300 miles from another. If Moscow ordered to fire the

missiles at U.S. targets, the Soviet commanders in Cuba would need between 14

and 24 hours to truck the warheads across miles of often treacherous terrain.

Recognizing that this was too long a lead time, Statsenko,

on October 27, ordered some of the warheads moved closer to the farthest

regiment, shrinking the lead time to ten hours. Kennedy knew nothing about

these logistical challenges. But their existence suggests yet again the role of

luck.

Had EXCOMM learned

of these difficulties, the hawks would have had a stronger argument in favor of

an all-out strike on Cuba—which would probably have disabled the missiles but

could have led to a war with the Soviet Union, whether in Cuba or Europe.

The Soviet troops

in Cuba had no predelegated authority to launch

nuclear missiles at the United States; any order had to come from Moscow. It is

also doubtful that the Soviets in Cuba had the authority to use shorter-range

tactical nuclear weapons in the event of a U.S. invasion. Those weapons

included nuclear-armed coastal cruise missiles and short-range rockets shipped

to Cuba with Statsenko’s division. During a long

meeting in the Kremlin that began on the evening of October 22 and lasted until

the wee hours of October 23, the Soviet leaders debated whether the Americans

would invade Cuba and, if so, whether the Soviet troops should use tactical

nuclear weapons to repel them. Khrushchev never admitted that the entire

operation was folly, but he did speak about grave mistakes. The upshot of this

meeting—which coincided with Kennedy’s speech announcing the naval blockade—was

an order to Pliev to refrain from using either

strategic or tactical nuclear weapons except when ordered by Moscow.

There was no American

invasion, and the order to fire the missiles never came. If it had, however, it

would undoubtedly have been followed to the letter. Statsenko’s

report noted that he and those under his command “were prepared to give their

lives and honorably carry out any order of the Communist Party and the Soviet

government.” His words highlight the fallacy that military leaders might

act as a check on political leaders bent on starting a nuclear war: military

officials in Cuba were never going to countermand political authorities in

Moscow.

The Absence Of Brains

Although Khrushchev

raved and raged in the first two days after Kennedy declared the naval

blockade, accusing the United States of duplicity and “outright piracy,” on

October 25, he changed his tune. That day, he dictated a letter to Kennedy in

which he promised to withdraw the missiles in exchange for an American

nonintervention pledge in Cuba. Two days later, he added the removal of U.S.

Jupiter missiles in Turkey to his wish list, confusing Kennedy and dragging out

the crisis. In the end, Kennedy decided to take the offer. He instructed his

attorney general brother Robert to meet with Anatolii

Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador in Washington.

On the evening of

October 27, Robert Kennedy made an informal pledge to remove the Jupiter

missiles from Turkey but insisted that the concession remain secret. Newly

available cables from Moscow to Dobrynin show how

important this assurance was to Khrushchev. The ambassador was presumably

instructed to extract the word “agreement” from Kennedy so Khrushchev could

sell the deal as an American capitulation to his inner circle. By creating the

impression that Kennedy was also making concessions, the word “agreement” would

help rebrand a surrender as a victory, a Cuba-for-Turkey exchange.

By this point,

however, Khrushchev was eager for a deal. A series of disturbing events had

spooked him. On the morning of the 27th, an American U-2 had been shot down

over Cuba by a Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missile on the orders of senior

Soviet officers in Cuba. The Soviets in Cuba always assumed that there would be

a U.S. invasion, and they blamed the Cubans for failing to detect the American

reconnaissance flights before the crisis. Accordingly, as the declassified

files reveal, Malinovsky presented the downing of the U-2 to Khrushchev as a

necessary measure to prevent the Americans from taking more photographs of

Soviet bases. He registered no awareness in his missive to Khrushchev that the

shoot-down could have become a prelude for World War III. Nor did Statsenko, when he later reported the shootdown

matter-of-factly, likewise portraying it as a routine response that the Soviet

military was trained and entitled to do.

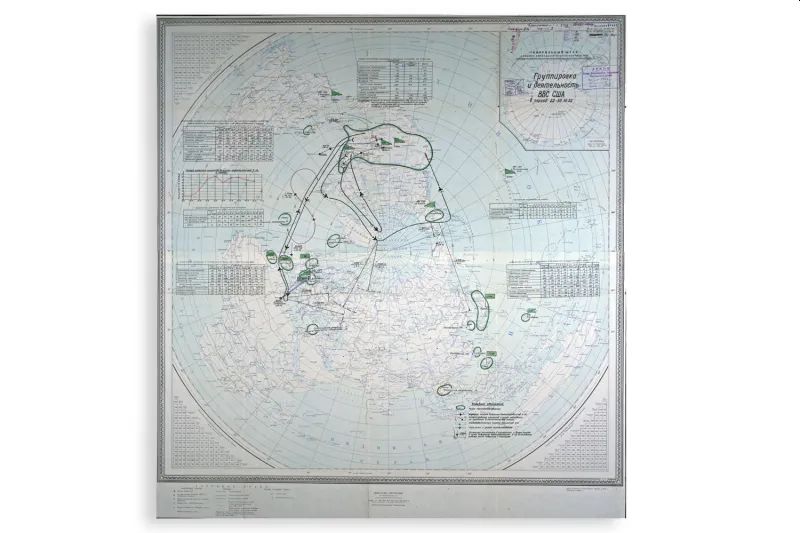

In the middle of the

day, another incident involved an American U-2: a plane sent to the Arctic to

sample the atmosphere for radiation got lost and accidentally flew into Soviet

airspace. The Soviet military dutifully mapped its progress on now declassified

maps, showing the number of hours American planes would need to reach targets

in Soviet territory.

However, the most

disturbing development was a plea Castro sent early on October 27, Havana time.

He asked Khrushchev to launch a preemptive nuclear strike against the United

States if the Americans dared to invade Cuba. Historians have long been aware

of this plea, but thanks to the new documents, we know more about what

Khrushchev thought of it. “What is it—a temporary madness or the absence of

brains?” he fumed on October 30, according to a declassified dictation taken by

his secretary.

Khrushchev was

emotional, but he pulled back from the brink in the hour of greatest danger. As

he put it to an Indian visitor on October 26, according to the newly released

documents, “From the experience of my life, I know that war is like a card

game, though I never played and never play cards.” That final qualification

wasn’t entirely truthful: to Khrushchev, the whole Cuban operation was one big

poker match he thought he could win by bluffing. But at least he knew when to

fold. On October 28, he announced that he would dismantle the missiles.

Learning And Forgetting

Since 1962,

historians, political scientists, and game theorists have endlessly rehashed

the Cuban missile crisis. Volumes of documents have been published, and

countless conferences and war games have been held. Graham Allison’s classic

crisis account, Essence of Decision, was published in 1971 and

updated in 1999 with the help of Philip Zelikow. One of the original book’s

conclusions, also included in the revised edition, has stood the test of time:

the crisis was “the defining event of the nuclear age and the most dangerous

moment in recorded history.”

But the declassified

Soviet documents make some important corrections to the conventional view,

highlighting the Achilles’ heel of the Kremlin’s decision-making process, which

persists: a broken feedback mechanism. Soviet military leaders had minimal

expertise in Cuba, deceived themselves about their ability to hide their

operation, overlooked the dangers of U.S. aerial reconnaissance, and ignored

experts' warnings. A small coterie of high officials who knew nothing about

Cuba, acting in extreme secrecy, drew up a sloppy plan for an operation doomed

to fail and never allowed anyone else to question their assumptions.

Indeed, the failure

of the feedback mechanism led to the crisis's immediate cause, the poorly

camouflaged missiles. Allison and Zelikow concluded that this oversight was not

the result of incompetence but a consequence of the Soviet military mindlessly

following its standard operating procedures, which had been “designed for

settings in which camouflage had never been required.” In this view, the Soviet

forces failed to adequately camouflage the missiles simply because they had

never done so.

A Soviet map detailing the progress of American U-2

planes

The new evidence

gives a different answer. The Soviets fully appreciated the importance of

hiding the missiles, and Khrushchev’s entire strategy was predicated on the

flawed assumption that they could do just that. The Soviet military officers in

Cuba also knew the importance of concealing the missiles. They recognized the

danger of U.S. aerial reconnaissance, tried to address it by proposing better

sites, and failed. The core of the problem was the original carelessness and

incompetence of Biryuzov. His offhand conclusion that

the missiles could be hidden under the palm trees was passed on as

unimpeachable truth. Military experts far below him in the hierarchy noted that

the missiles would be exposed to U-2 overflights and duly reported the problem

up the chain of command. Yet the planners in the general staff never corrected

it, unwilling to bother their superiors or question the idea of the entire

operation. Operation Anadyr failed not because the Soviet rocket forces were

too wedded to their standard procedures but because the military’s

hyper-centralization prevented the feedback mechanisms from working properly.

In their first

reports analyzing the crisis—part of the new trove of documents—Soviet military

leaders engaged in a blame game. Ignoring his culpability, Biryuzov

pointed the finger at “the excessive centralization of management” of the

operation “at all stages in the hands of the general staff, which chained

the initiative below and reduced the quality of decision-making on

specific questions” on-site in Cuba. He never admitted the lack of camouflage

as the main flaw of Anadyr, although his political superiors immediately

recognized it as such.

Anastas Mikoyan, a member of the Presidium whom Khrushchev

had dispatched to Havana to arrange the withdrawal of missiles, spoke to the

Soviet officers in Cuba in November. He tried to turn the lack of camouflage

into a joke. “The Soviet rockets stood out like during a parade on the Red

Square—but erect,” he told Pliev and his comrades.

“Our rocket men decided to give Americans a middle finger this way.” Mikoyan

even soothed their anguish about the missiles’ discovery, saying that West

German intelligence, not the U-2, discovered the Soviet missiles. (The West

Germans had picked up some evidence but hardly the smoking gun that the U-2

flight uncovered.) And he alleged that once the Soviet missiles were spotted,

they no longer served any purpose of deterrence—a preposterous claim, given

that missiles could hardly deter the United States it didn’t know about.

Despite Mikoyan’s best efforts, Soviet commanders and officers took the order

to leave Cuba as a humiliating retreat. Many had to recover from nervous breakdowns,

recuperating at Black Sea resorts near the ports they sailed to Cuba.

Khrushchev was eager

to cover his retreat. He deliberately avoided any criticism of the Soviet

military’s performance in Cuba. Although the planning errors were plain, the

Soviet leader was more interested in depicting the debacle as a victory than

assigning responsibility for the mishaps. In this, his interests overlapped

with those of the Soviet supreme command, which wanted to avoid responsibility,

so the secret fumbles of Operation Anadyr were swept under the rug. Documents

about the operation were boxed up and sent to gather dust in the archives,

where they remained sealed until last year. Biryuzov

was promoted to the head of the general staff. His career remained untarnished

until he died in 1964 when he perished in a plane crash five days after

Khrushchev was overthrown by his Presidium colleagues.

Soviet military

officials viewed operation Anadyr, not as a colossal failure but as a shrewd

ploy that almost worked. The lessons they learned were simple: had the Soviets

done a better job of coping with the enormous logistical challenges, had they

tried harder to hide the missiles, or had they shot down U.S. reconnaissance

planes earlier, with a little bit of luck, Operation Anadyr could indeed have

succeeded. Statsenko, for all his insights, became

fixated on U-2s and recommended in his report that the Soviets urgently develop

a technology—“invisible rays”—which would allow them to “distort” the images

captured by the reconnaissance planes or perhaps expose the film they carried.

It never occurred to him that the whole operation was a bad idea. The entire

point of his postmortem was to explore ways to send strategic missiles “to any

distance and deploy them on short notice,” that is, do the same thing again,

but do it better. Perhaps Statsenko deemed it above

his pay grade to question the bright ideas sent from on high.

Only in the late

1980s, during Mikhail Gorbachev’s “new thinking,” did a different view of the

crisis emerge within the Soviet Union. Inspired largely by the American

literature on the episode, Moscow saw the crisis as an unacceptably dangerous

moment. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, fears of a nuclear

conflict receded, and for Russia, the Cuban missile crisis lost immediate

political relevance and became plain old history. Veterans of the crisis

embraced heroic narratives of their exploits. In his assessment of the crisis

in the first decade of this century, Anatoly Gribkov,

a general who helped plan Operation Anadyr, declared that the Soviet military’s

performance was “an example of the finest military art.” Embarrassing failures

were mostly forgotten. Castro, who had horrified Khrushchev by proposing to

nuke the United States, later strenuously denied doing so. But all agreed that

the Cuban missile crisis was never to be repeated.

Back On The Brink

Although Russia remains

committed to avoiding nuclear war, Putin seems to stoke fears of such a

conflict. Like Khrushchev, Putin is rattling the nuclear saber to prove to

everyone—and perhaps above all to himself—that Moscow will not be defeated.

Also, like Khrushchev, Putin is a gambler, and his misadventure in Ukraine

suffers from the same feedback failures, excessive secrecy, and

hyper-centralization that plagued Khrushchev in Cuba. Just as Khrushchev’s

lieutenants failed to question his rationale for aiding Cuba, so Putin’s top

ministers and advisers did not resist his claim that Ukrainians and Russians

were one people and, therefore, Ukraine had to be “returned” to Russia by force

if need be.

Facing no pushback,

Putin turned to Sergei Shoigu, his minister of defense, and Valery Gerasimov,

the head of the general staff, to carry out his will. They failed even more

spectacularly than their predecessors had in 1962, hobbled by the same

structural impediments that ruined Operation Anadyr. The general staff has

never digested the awkward details of the story of Khrushchev’s failure, even

with the declassification of this new batch of documents.

As he peered uneasily

over the brink of nuclear apocalypse, Khrushchev found time to mediate in the

monthlong Sino-Indian War, which broke out during the Cuban missile crisis.

“History tells us that to stop a conflict, one should begin not by exploring

why it happened but by pursuing a cease-fire,” he explained to that Indian

visitor on October 26. He added, “What’s important is not to cry for the dead

or to avenge them but to save those who might die if the conflict continues.”

He could have been referring to his fears about the events brewing that day in

the Caribbean.

Terrified by those

developments, Khrushchev finally understood that his reckless gamble had failed

and ordered a retreat. Kennedy, too, opted for a compromise. In the end,

neither leader proved willing to test the other’s redlines, probably because

they did not know where exactly those redlines lay. Khrushchev’s hubris and

resentment led him to the worst misadventure of his political career. But

his—and Kennedy’s—caution led to a negotiated solution.

Their prudence holds

lessons for today when many commentators in Russia and the West call for a

resolute victory of one side or the other in Ukraine. Some Americans and

Europeans assume that the use of nuclear weapons in the current crisis is

completely out of the question. Thus, the West can safely push the Kremlin into

the corner by obtaining a comprehensive victory for Ukraine. But plenty of

people in Russia, especially around Putin and among his propagandists,

defiantly say there would be “no world without Russia,” meaning that Moscow

should prefer a nuclear Armageddon to defeat.

If such voices had

prevailed in 1962, we’d all be dead now.

For updates click hompage here