By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Some observers have

approvingly claimed that the second Trump administration heralds a realist

revival in American foreign policy. Robert O'Brien, who served as national

security adviser in the first Trump administration, eagerly promised “the

return of realism with a Jacksonian flavor.”

This view is gravely

mistaken. Realists often disagree, sometimes sharply, about the best course of

action, so it is not easy to say what a “realist foreign policy” is. But it is

easy to say what is not—and Donald Trump’s brand of “America first” is not.

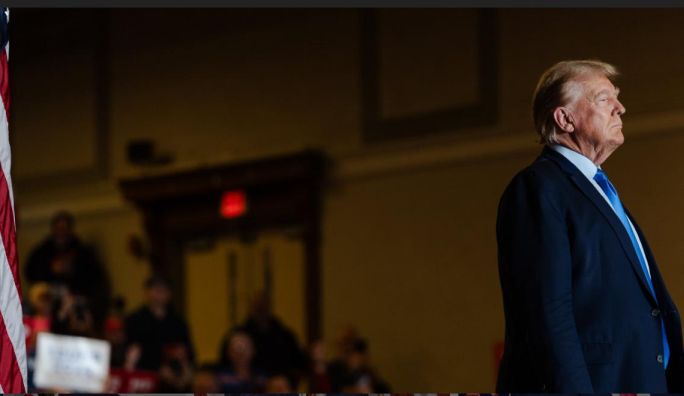

President Donald Trump signing executive orders,

Washington, D.C., January 2025

Get Real

Although there never

will be a single “realist foreign policy,” there remain identifiable realist

dispositions. Realists are generally skeptical of the stopping power of

international law, reluctant in most (but not all) cases to pass confident

judgment on competing claims to the moral high ground proffered by opposing

sides in international conflicts, and generally wary of ambitious schemes to

settle distant conflicts through the use of force.

From those

dispositions flow a number of core tenets. Those principles can suggest a range

of policy choices. It is notable, however, the extent to which Trump rejects

these credos.

Realism can be coolly

calculating and hardhearted, but it is not reflexively violent, or indifferent

to the moral implications of policy choices. Actors in world politics who

ruthlessly apply the use of force are sometimes dubbed (and occasionally admired)

as realists. But as Clausewitz taught, the use of force can be deemed

successful only if it achieves the political goals for which it was introduced

at an acceptable cost. “No one starts a war—or rather, no one in his senses

ought to do so—without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve

by that war,” he lectured. “The political objective is the goal.”

Foreign policy is

about getting what you want on the world stage. A thin reading of Machiavelli

might yield the cherry-picked homily that it is better for a prince to be

feared than to be loved; nevertheless, in world politics, only a fool wants to

be hated. The ability to marshal one’s political influence and wield it wisely

is a key determinant of success or failure by that fundamental metric of

achieving one’s objectives in the international arena. But Trump’s brand of

“America first” is not very good at international politics. Consider U.S.

competition with China. During the Cold War, the last major great-power contest

Washington faced, the diplomat George F. Kennan described the challenge the

United States faced and the objectives it sought as political rather than

military. The principal threat was not that the Soviet Union would imminently

add Western Europe to its empire through conquest but that, over time, the

entire continent would slowly slide into the Soviet sphere of influence.

And regardless of whether U.S.-Chinese relations today constitute a new cold

war, Kennan’s assessment applies. The principal danger is not that China will

recklessly and foolishly engage in a self-defeating bid for regional hegemony

by serially invading its neighbors; the danger is that China might come to

achieve political domination over East Asia.

That is why, from a

realist perspective, although U.S. military preparedness matters, the

cornerstone of a wise response to the China challenge would be close political

partnerships (and committed alliances) with key players in the region. Yet

Trump evinces a curious attitude about alliances, viewing them not so much as

mechanisms to bolster shared sensibilities but as generally disdained

money-losing propositions populated by ungrateful free-riders on American

largess. Now those countries must assess whether or not Washington will be a

reliable political partner. If the United States seems mercurial or

untrustworthy, China may come to dominate the region—not by military

conquest, but as a result of calculations by those who conclude there is no

practical alternative to acceding to its wishes.

Trump’s aversion to

alliances is also likely to shape his choices when it comes to the war in

Ukraine. From a realist perspective, it is in the American national interest to

live in a world where aggressive wars of conquest by ambitious authoritarian

powers fail rather than succeed. Better yet if one can hasten that failure at a

relatively low cost, and if doing so draws one’s allies even closer. That is

precisely what has happened since Russia’s initial invasion in 2022—which is

why it is so galling that Trump’s allies have cast his seeming inclination to

bring about an end to the war on Russia’s terms as an act of realist restraint

rather than pure folly.

From a realist

perspective, it is past time to reassess American security guarantees in the

Persian Gulf, which might have made sense a half century ago but are now

plainly anachronistic. It is also hard to see how providing Israel a blank

check for its expansionist policies in the West Bank advances the American

national interest. Yet in assessing Washington’s long-standing friends and

allies, Trump seems content to carry on Washington’s embrace of Israeli Prime

Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Trump also seems untroubled by U.S. military

commitments in the Gulf and has talked tough about confronting Washington’s

main nemesis in the region, Iran. But the United States is now the world’s

largest energy exporter and faces growing threats in other regions. A true

realist would thus suggest that Washington gracefully disentangle itself from

promises to defend the Gulf and would warn that an American (or U.S.-backed)

attempt to take out Iran’s nuclear program by force would be a

catastrophic blunder.

Big Mouth

Realism is often

associated in the popular imagination with toughness. And although it is often

essential to communicate firmness to adversaries, especially in private,

realists don’t bother with trash talking, and they very rarely strut.

In sharp contrast,

Trump has been especially loud in recent weeks. In addition to repeatedly

threatening to seize the Panama Canal, Trump used a Christmas message to

belittle the prime minister of Canada and suggested that Canadians would be

better off if their country became the 51st U.S. state. But realists would be

loath to undermine one of the greatest advantages the U.S. has long enjoyed as

a world power—uncommonly warm relations with its closest neighbors. Trump

has also talked plainly about using coercive tactics against an ally to bring

about the absorption of Greenland, which he claimed “is needed by the United

States for National Security purposes.” And although realists don’t place much

stock in rhetoric, such talk can matter—in a bad way—by shaping international

expectations about American intentions to the detriment of U.S. interests.

Imagine if similar sentiments were uttered by the incoming leader of another

great power. Talk is cheap—but can often backfire.

Nowhere is this more

evident than in Trump’s saber rattling about the international role of the U.S.

dollar. “Many countries are leaving the dollar,” he claimed, falsely, during

the 2024 campaign. “They not going to leave the dollar with me,” he boasted.

“I’ll say, ‘You leave the dollar, you’re not doing business with the United

States, because we’re going to put a 100 percent tariff on your goods.’”

Ultimately, however, the future of the greenback as an international currency

will largely be determined by the collective choices of uncoordinated private

actors, most of whom will be impossible to identify. International money runs

on confidence: people use it because they want to use it (often fleeing

alternatives, including their local legal tender). Trying to force others to

use the dollar would make them want to use it less—and undermine its

credibility.

Given the priority

that countries place on retaining their policy autonomy and advancing their own

interests, realists presume that states prefer not to be pushed around and will

balance against bullying when they can. Arrogance and the gratuitous throwing

of sharp elbows is not realism. The philosopher Raymond Aron detailed the

self-defeating nature of such behavior, which invariably excites “the fear and

jealousy of other states,” weakening rather than strengthening the national

hand and nudging “a shift of allies to neutrality or of neutrals to the enemy

camp.” Thucydides observed a similar phenomenon at the outbreak of the

Peloponnesian War, reporting the widespread “indignation felt against Athens.”

Due to years of Athenian presumptuousness, he wrote, “Men’s

feelings inclined much more to the Spartans.” Athens

lost.

One of Trump’s

signature “America first” ideals fails to account for that dynamic: the imposition

of protectionism, either for its own sake or as a negotiating tactic designed

to bend others to the American will. U.S. protectionism would elicit

retaliation that would severely damage an economy that exports around $3

trillion in goods and services annually and relies on imported intermediate

products even for domestic production, and it would send the domestic price of

tradeable goods soaring. Trump’s embrace of tariffs and other trade barriers

would also present openings for others. In December, the European Union reached

a trade pact with four South American countries, forming one of the world’s

largest trading zones. China is similarly making important economic inroads in

the Western Hemisphere. Trump’s aggressive trade policies, even if they manage

to eke out grudging concessions from others, will undermine broader U.S.

foreign policy goals (such as inhibiting the breadth of China’s political

reach), contribute to global economic distress, and leave other countries wary

of (and looking to defend themselves from) Washington’s next attempt to throw

its weight around.

A Failed Approach

In thinking about

foreign policy, most realists align with the diplomat and scholar Arnold

Wolfers, who coined the term “milieu goals.” As Wolfers wrote, although states

must prioritize their own survival, they are “faced with the problem of

survival only on rare occasions.” As always, realists will disagree on the

specific tactics that will best achieve milieu goals, but they well understand

that comity with friends is as essential for national security as judicious

firmness with adversaries.

Here again, “America

first” rejects the realist emphasis on the long run: it is a shortsighted, transactionalist, and narrowly selfish approach. Trump sees

every interaction with other countries, friends and foes alike, as a zero-sum

confrontation in which the objective is to extract the largest possible share

of the perceived visible gains. Washington tried this approach before, in the

interwar years. Its myopic demands for repayment of its war debts contributed

to the financial fragility that led to the shattering global financial crisis

of 1931. Its protectionism (in the wake of which its exports fell by even more

than its imports) spurred the collapse of world trade more generally. Both

policies contributed to and deepened the global depression, which was an

important factor in bringing fascists to power in Germany and Japan. That

original incarnation of “America First” was penny-wise but more than

pound-foolish, and it was certainly not predicated on realism. Neither is

Trump’s version—and the results could once again be disastrous.

For updates click hompage here