By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

How to End the Democratic Recession

On August 5,

following weeks of mass student protests, a dictator fell in the world’s eighth

most populous country. Amid wars in Ukraine and Gaza, the escalating danger of

a wider conflict in the Middle East, and the twists and turns of the U.S.

presidential race, the sudden resignation and flight into exile of Bangladesh’s

prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, drew slight global attention. But the

significance of her ouster could prove substantial. Hasina, the daughter of the

independence leader and first president of Bangladesh, first served as prime

minister from 1996 to 2001 and was elected to the office again in 2008. In

three successive terms over the next 15 years, she ruled with mounting

ruthlessness and resolution. She asserted personal control over the courts,

prosecutors, government agencies, and the police, using them to silence the

media, persecute her opponents, cow private business, and subvert the

institutions and traditions that previously allowed for reasonably free and

fair elections. By the time Bangladeshis voted again, in 2014, Hasina had so

trampled on constitutional norms that most opposition parties chose to boycott

the election, accelerating the country’s descent into autocracy and misrule.

Yet Bangladesh’s civil society refused to remain silent in

the face of a rising tide of arrests and disappearances. In January 2024, as

Hasina prepared to glide into a fourth consecutive term in another unfair

election (which also was boycotted by the opposition), popular protest

intensified. In June, the dam burst. The trigger was a seemingly modest issue:

the reinstatement of a quota system for government jobs that was seen to favor

Hasina’s political base. Bangladeshi university students took to the streets,

angered by the prospect of a spoils system. Hasina responded with repression:

her party’s shock troops joined the fray, and she sent in the police and the

military. Over the next two months, hundreds of civilians were killed, more

than 20,000 injured, and more than 10,000 arrested. The government’s brutality

turned a limited protest movement into a nationwide civil disobedience campaign

against tyranny and corruption. In the end, after losing the support of the

military, Hasina fled to India.

One could argue that

bringing down a dictator was an easier job in Bangladesh than it would be

elsewhere. No Bangladeshi party or movement had institutionalized ideological

and political control over the state, security apparatus, and economy the way

revolutionary communist parties had in China, Cuba, and Vietnam, the ayatollahs

had in Iran, or, to a lesser extent, Hugo Chávez’s

“Bolivarian socialist” movement had in Venezuela.

However many of the autocratic regimes that have emerged in the past decade

have followed a path similar to Bangladesh’s. Corrupt leaders have hollowed out

democratic institutions and established authoritarian rule behind the façade of multiparty elections. Following a common

playbook, they wholly dismantled democracy in El Salvador, Hungary, Nicaragua,

Serbia, Tunisia, Turkey, and Venezuela. Elsewhere, similar tools have been used

to degrade democracy. However, whether those countries crossed the line into

autocracy is debatable: recent examples include Georgia, Honduras, India,

Indonesia, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka. Illiberal practices have also eroded

the quality of democracy and the public’s support for it in Botswana and

Mauritius, Africa’s oldest multiparty systems. Corrupt and domineering ruling

parties in Mongolia and South Africa have overseen democratic declines,

although recent elections dealt severe setbacks to both. In Mexico, by

contrast, a move by Andrés Manuel López Obrador as outgoing president could further erode

the country’s precarious rule of law. A new constitutional amendment requires

all judges to be popularly elected, undermining the independence of the

judiciary and putting the future of the country’s democracy at risk.

Most of these

countries are not full-blown dictatorships. Rather, they have joined (or

gravitated toward) the ranks of what the political scientists Steven Levitsky

and Lucan Way term “competitive authoritarian” regimes. The description

encompasses a core contradiction. The ruling elites will not commit to the

constitutional norms that allow for free elections and government

accountability, but the people will not tolerate the complete elimination of

individual freedoms, civic pluralism, multiparty elections, and at least the

possibility of parties alternating in power. Many countries, such as Kenya,

Nigeria, and Tanzania, have lingered in this halfway house for some time.

Others, such as Pakistan and Thailand, do so with the added complication of

militaries that hold political veto power.

The global outlook

for democracy is clouded, if not downright disheartening. Political extremism,

polarization, and distrust have been on the rise even in long-established

liberal democracies, and doubt about the democratic commitment of one of the

two major-party candidates is a major issue in the U.S. presidential race this

year. But there are glimpses of sun behind the clouds. Bangladesh is not the

only example. The struggle for freedom escalated in Venezuela after a stolen

election in July, with the opposition presenting overwhelming evidence of its

landslide victory. Thailand’s military-backed regime has faced a deepening

crisis of legitimacy since courts blocked the winner of the May 2023

parliamentary elections from taking power. Turkey’s electoral autocracy looks

increasingly worn and fragile, with the country’s long-ruling strongman, Recep

Tayyip Erdogan, barely eking out a victory over a colorless opponent in the May

2023 presidential vote. Last year as well, stunning opposition victories in national

elections brought a restoration of democratic practices in Poland and a

historic opportunity in Guatemala

to move past the country’s troubled history of autocracy and corruption. And

the past two election cycles in Malaysia suggest a shift toward democracy after

six decades of what seemed a stable competitive authoritarian regime: a

makeshift coalition ended the six-decade rule of the Barisan Nasional coalition

in 2018, and voters then made the principal opposition leader, Anwar Ibrahim,

prime minister in 2022.

In other words,

today’s autocrats are not invincible. Many rely on elections, albeit deeply

flawed ones, to maintain an air of legitimacy. But this means they can be

defeated. Determined domestic opposition fronts, backed by the larger community

of liberal democracies, can reverse the trend of global democratic backsliding.

To be successful, they will need to grapple with the drivers of the

antidemocratic trend, weaken the pillars that prop up the fake democracy of

authoritarian populism, and apply the lessons of previous successful campaigns

against authoritarian rulers. Just as autocrats employ a common set of tools to

acquire and maintain power, their opponents must start following the playbook

for democratic change.

Democracy In Retreat

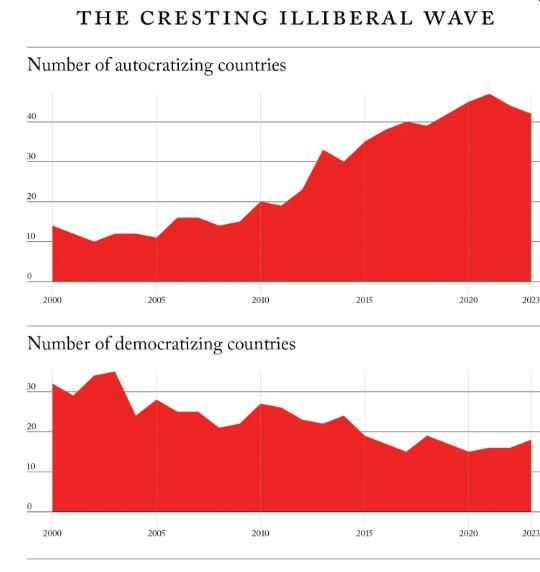

Democracy’s global

momentum peaked soon after the end of the Cold

War. For the first time in history, systems in which people could choose

and replace their leaders in free and fair elections became the predominant

form of government. By 2006, about three-fifths of all countries met this

standard. Since then, democracy and freedom have been in steady retreat. For 18

consecutive years, the nonprofit group Freedom House—which tracks changes in

political rights, civil liberties, and the rule of law and assigns countries

and territories an annual “freedom score” on a scale of zero to 100—has counted

more countries losing freedom than gaining it. Often, the difference is a

two-to-one ratio or worse. The Swedish-based project V-Dem has identified a

similar but somewhat more recent unfavorable trend.

The decline has been

global. Average levels of democracy, as measured by Freedom House, V-Dem, and

the Economist Intelligence Unit, have dropped in every region of the world

since 2006. The changes have not always been disastrous, but they have been

remarkably broad and persistent. Of the 22 sub-Saharan countries that shifted

significantly on democracy scales during this period, 18 underwent declines,

and of the four that improved, three—Angola, Gambia, and Zimbabwe—simply became

less abusive autocracies. Globally, those three are outliers; most autocracies,

including Cambodia, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Myanmar, and Russia, have

become significantly more repressive.

The euphoria that

attended the heady expansion of democracy from the mid-1970s to the first few

years of the twenty-first century—the “third wave” of democratization—now seems

a distant memory. A few places, such as Armenia, Bhutan, Colombia, Malaysia, Moldova,

and Taiwan, have seen notable gains in recent years, but genuine democratic

breakthroughs have been few and far between. Iran’s government crushed one

popular rising, the Green Movement, in 2009 and another, the Woman, Life,

Freedom movement, in 2022. All the Arab Spring uprisings were ultimately

suppressed save for the one in Tunisia, where a fledgling democracy stumbled on

until the president moved to dismiss parliament and the prime minister in 2021.

The same year, Myanmar’s military ended an experiment in semi-democracy when it

overturned the results of the country’s 2020 elections, closed parliament, and

arrested senior civilian officials, plunging Myanmar into a bloody conflict.

Autocratic Enablers

What sent the world

spinning toward autocracy? The answer varies from country to country, but

certain factors stand out. To some extent, a course correction may have been

inevitable as democracy spread to many countries that lacked the economic base

and rule-of-law institutions to control corruption and deliver sustained

progress. Yet this does not explain every case of backsliding; some very poor

countries, such as Liberia and Malawi, have largely managed to keep their

democratic gains.

Another driver is the

series of reputational blows that liberal democracy suffered in the first

decade of the twenty-first century. First, the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq

tarnished the idea of promoting democracy by linking it to the use of military

power to force regime change—to disastrous effect. Then, only a few years

later, a global financial crisis destabilized many governments, including

democratic ones. It had originated in the United States, a supposed model

democracy, when the country’s mortgage industry came crashing down after a

decade of government failure to rein in predatory practices.

It was not just

democracies that sullied their own image; illiberal actors helped them along.

China used its growing wealth, propaganda, technology, and mechanisms of covert

influence to promote its authoritarian governance model and dim the attractions

of open societies. The Russian government worked in similar ways to denigrate

democracy and destabilize democratic institutions, such as by intervening in

elections. After taking office in 2010, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban

crafted a deeply illiberal pseudo-democracy that appealed to far-right

anti-immigrant and nationalistic forces around the world.

At first, social

media enabled citizens to circumvent autocratic states’ control of information

and organize for democratic change. Although online platforms are still used

for these purposes, their positive role has been overshadowed by the advance of

authoritarian means of digital surveillance and repression and by the

polarizing effects of social media algorithms, which autocracies can exploit to

divide and demoralize democratic societies. Artificial intelligence is now

beginning to supercharge these efforts.

The digital

technology boom joined a snowballing set of global trends that undermined

popular support for democracy and created fertile ground for the rise of

illiberal populist parties. Dramatic increases in income inequality in both

advanced and emerging economies meant soaring wealth for a small fraction of

top income earners and economic stress for much of the middle and lower

classes, which became pessimistic about the future and cynical about the

parties and politicians who had failed them. Inequality then fed into political

polarization, which was further intensified by the accelerating movement of

diverse people, ideas, and cultures across borders and by campaigns for gender

and racial equality that upset long-settled hierarchies of social status. To

exploit the public backlash, politicians in many advanced democracies,

particularly in Europe and the United States, framed large waves of immigration

as a threat to economic health, social stability, and national character. Their

rhetoric severely distorted reality, but it played to people’s fears.

These trends

coincided with a historic shift in global power. From 1960 to 1990, the U.S.

share of global economic output declined from two-fifths to around one-quarter,

where it remains, and Europe’s share has shrunk since 1960 by roughly half. At

its peak in the early 1990s, Japan accounted for nearly one-fifth of global

GDP; now its share is just three percent. Meanwhile,

China has risen to become the world’s second-largest economy, ranking behind

only the United States, and India’s economy is now closing in on Germany’s and

Japan’s. China and Russia have used corruption, coercion, and propaganda to

sway and subvert open societies, and their militaries have cast long, alarming

shadows in their respective neighborhoods. In sum, while Beijing and Moscow (and

Tehran) bully their way into reshaping world politics, the advanced

democracies, with their diminished economic and geopolitical standing, have a

weakened hand and are playing it cautiously. The “unipolar moment” immediately

after the Cold War, when autocrats made political decisions under the shadow of

American power, is long past.

At a rally in Dhaka, Bangladesh, September 2024

Then there is the

human factor. Restraint in the exercise of power is not a natural tendency.

This is why the framers of the first constitutional democracy, the United

States, understood the need to check and balance power, following the

Madisonian principle that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” “If

you want to test a man’s character,” goes one aphorism, “give him power.”

Unencumbered by strong constitutional guardrails, most men—and, like Sheikh

Hasina and Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi before her, some women—who get

the opportunity fail the test.

Over the past two

decades, critical constraints on human behavior have lifted. Ambitious

politicians have observed the rhetoric and methods their peers abroad have used

to dismantle democracy, piece by piece. These aspiring autocrats have learned

from examples of success and acted on those lessons, emboldened by the

inability of domestic and international actors to restrain them. Once, the

diffusion of political ideas helped foster democratic transitions. Today, it

facilitates democratic backsliding.

Furthermore,

constitutions restrain rulers only if they are enforced. When these documents

are embedded in norms, incentives, and expectations, violations are rare and

tend to fail because powerful actors rise to reaffirm the constitutional order

out of both conviction and self-interest in sustaining the rules of the game.

But when severe political polarization generates a sense of existential risk—a

fear that losing an election could mean the permanent loss of political power

and even one’s livelihood and freedom—these dynamics change. A politician with

sufficient skill and will to override constitutional norms can embark on the

road to autocracy.

Exposing the Fraud

Today’s autocrats

mainly come to power at the ballot box, and they remain in power while

maintaining a façade of competitive elections. Of

the roughly 30 countries that have lost their democracies since 2006, all but

three (the Sahelian coup countries—Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger) have followed

this pattern. Holding votes gives autocrats a claim to legitimacy, but it also

makes them vulnerable. The elections they stage may be deeply unfair, but the

incumbent autocrat can still lose and be compelled to leave office. To restore

democracy through elections, however, domestic defenders of democracy and their

supporters abroad must be able to identify authoritarian populism and

understand how it works.

First, authoritarian

populists purport to defend “the people”—the true, virtuous majority—against a

corrupt establishment that has hijacked power and exploited them. In this

narrative, there are not just good and bad policies; there are good and evil

people. The ruling elites and their allies are morally bankrupt and must be

vanquished, even as some of those allies, especially in the business community,

opportunistically throw in their lot with the populists. Drawing so stark a

divide enables the populist contender to claim a mandate to persecute opponents

and purge the civil service on coming to power. Resorting to that tactic

explains another key feature: populists are anti-institutional. They disparage

the existing economic and political institutions, even the constitution itself,

as the rotten structures of a rotten elite. Then they dismantle institutional

safeguards and weaponize state power.

On a societal level,

populists reject pluralism. They see no need to make space for multiple ways of

thinking and believing. The country has one identity, and people who are

different—by faith or ideology or national origin or sexual identity—are

deviant and dangerous. They must be watched, controlled, or removed. Finally,

populism is personalistic and hegemonic. Since leaders are the saviors of their

countries against evil forces, they must be granted extraordinary unfettered

power. Elections are no longer instruments of political accountability and

constraint but rather plebiscites to revalidate leaders and their political

monopolies.

Inevitably, an

authoritarian populist regime becomes intolerant, xenophobic, and corrupt. More

than its bigotry—perhaps even more than its violation of democratic norms—this

corruption, drawn from a sense of moral entitlement to gorge on public

resources, is its Achilles’ heel.

The key to defeating

authoritarian populism is to expose its vanity, duplicity, and venality, to

show it to be not a defense of the people but a fraud upon the people. This

requires independent reporting to reveal corruption. It requires using,

whenever possible, countervailing institutions—regulatory bodies, auditing

agencies, the judiciary, the police, the civil service, and, if there is a

significant opposition presence, the legislature—to disclose and curtail abuses

of the public trust. Elements of civil society, such as bar associations,

trade unions, student groups, and other professional and civic organizations,

can be important allies in this cause. Resistance is more effective when

mobilized early; the longer populist authoritarians hold on to power, the more

they chip away at institutional constraints. One reason illiberal parties did

not fully subvert democracy in Poland or, at first, in Mexico, unlike in

Hungary, Turkey, or Venezuela, is that they did not win sufficient majorities

in parliament or through a direct vote to amend the constitution. Enough

judicial and other institutional independence remained to limit the

authoritarian slide. That constraint was lifted in Mexico with the June

election when López Obrador’s party won enough seats

in Congress to push through constitutional change.

Turning the Tide

Once the

authoritarian project conquers the country’s institutions, resistance from

within the state is no longer possible. Mass mobilization is required to defeat

it. Success is much more likely if the democratic movement is peaceful and

operates within legitimate institutional boundaries. Demonstrations, strikes,

and other forms of nonviolent civil resistance may slow or halt the descent

into authoritarianism—or even force an autocrat to flee, as seen in Bangladesh

this year and in Ukraine after the Euromaidan protests of 2014. But the most

promising route is still through the ballot box. Repeatedly over the past

decade, in countries as diverse as Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Guatemala, Poland,

Senegal, Sri Lanka, Zambia, and—yes—the United States, democratic elections and

the enforcement of term limits have curtailed an authoritarian drift. In India

in May, they eroded the ruling Bharatiya Janata

Party’s iron grip on the parliament, which might diminish the party’s readiness

to abuse power to stifle dissent. In Belarus, Hungary, Turkey, and Zimbabwe,

opposition campaigns fell short, unable to overcome the obstacles posed by

entrenched authoritarian regimes to free and fair elections. But the progress

they made is notable. In Belarus’s case, the opposition candidate for president

likely won the 2020 election, but the dictator Alexander

Lukashenko declared patently false results.

Opposition

mobilization has worked in earlier eras, too. Globally, the third wave of

democratization was driven in part by opposition movements that overcame

repression and fraud by documenting their electoral victories through

independent vote tabulation at polling stations and by rallying mass protests.

The first successful “color revolution” to bring about a democratic transition

after a disputed election unfolded in the Philippines in 1986, followed by

Serbia in 2000, Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004–5, and Kyrgyzstan in 2005. In

a few other cases, ruling autocrats were stunned by their electoral defeats but

accepted the outcome and ceded power without the need for mass protests.

Both the earlier and

more recent electoral victories for democracy share other important

features. Opposition forces united behind a single electoral platform or, as in

Poland last year, coordinated their parliamentary campaigns to avoid dividing

the vote. In each case, the authoritarian ruling party was deeply unpopular,

internally divided, or both. In some cases, external pressure from liberal

democracies raised the costs of repression and encouraged defections by the

elite. And the incumbents’ ability to cling to power by using blatant

falsehoods and blunt force was constrained by independent media, divisions

within the security forces, or the latter’s unwillingness to fire on their own

people.

Successful campaigns

against authoritarian populists have shared some basic messaging strategies.

They craft broad political appeals to mobilize the largest possible electoral

base, even courting voters who supported the autocrat in the past. They seek to

unify the country, not divide it. Authoritarian populists thrive on and excel

at polarization; their democratic opponents must undercut that cynical

strategy. They must show empathy and humility, welcoming culturally,

ethnically, and ideologically diverse segments of society to join the

democratic cause. In Turkey, for example, the opposition’s astonishingly

successful municipal election campaigns in 2019 and 2024 pursued a strategy of

“radical love”—an explicit rejection of the ruling Justice and Development

Party’s rhetoric of hate and division. Democratic aspirants, moreover, must

call out the incumbent’s failures and must foreground issues that matter to

ordinary voters, such as improving the country’s economic performance, ending

corruption, and delivering services that will improve people’s lives. Their campaigns

should recapture patriotism, emphasizing pride in the nation as a democracy.

They should not be dour but rather present a confident vision of a better

future. They should not be boring, either. A successful campaign is one infused

with creativity, energy, passion, and even joy. Finally, as the political

scientist Steven Fish has urged, those seeking to unseat an autocrat cannot be

weak. They must project conviction, with forceful appeals to voters’ interests

and values. They must show that strongman rule is not the only form of strong

leadership.

Voting in Diyarbakir, Turkey, March 2024

External support is

also critical. Lately, however, liberal democracies have been sitting on the

sidelines as China and Russia stand behind autocrats who rig and

terrorize their way to electoral victory, such as Lukashenko in Belarus in

2020, Emmerson Mnangagwa in Zimbabwe last year, and Nicolás

Maduro in Venezuela in July, or, in the case of Pakistan, as the military

barred former Prime Minister Imran Khan from running for parliament in the

February election. Amid heightened strategic competition with an emerging axis

of autocracies that includes China, Russia, and Iran, powerful democracies,

particularly the United States and major European countries, are hesitant to

use all the diplomatic, informational, and economic tools at their disposal to

support democratic change.

To reverse the global

democratic slide, the liberal democracies must get back in the game. A test of

their resolve is already underway in Venezuela, where the opposition has

compiled official tallies from over 80 percent of polling stations to

demonstrate that its candidate, Edmundo González,

defeated Maduro in a landslide in the July presidential election. With the

backing of China, Russia, and Cuba, as well as the loyalty of the country’s

military and security establishment, Maduro has brutally repressed protests

demanding that he acknowledge the results and peacefully transfer power. Ending

Venezuela’s authoritarian nightmare, which has already prompted more than a

fifth of the population, some eight million people, to flee the country over

the past decade, now requires an intense diplomatic effort. Brazil, the United

States, and democracies in Latin America and Europe need to coordinate their

efforts to persuade Maduro and his allies to accept the opposition’s offer of

immunity from prosecution in exchange for a transfer of power. Negotiations

require carrots and sticks. An international coalition must not only prepare to

make painful concessions on amnesty (including shielding members of the

Venezuelan regime from prosecution in the United States and assuring them safe

passage abroad) but also threaten the elite with punishing sanctions on their

foreign assets and with blocking family visas if they continue to resist the

will of the Venezuelan people.

It is rare to

encounter such a glaring and well-documented example of an autocrat facing

electoral defeat and a broad, passionate societal aspiration for change.

Venezuela is ripe for a democratic transition, and the world’s liberal

democracies must do all they can to help it along.

Freedom Reborn

The challenges

confronting democracy today are formidable. Authoritarian regimes have gone on

the offensive to discredit and destabilize free societies. That they do so out

of fear and concern for their own legitimacy does not make their actions any

less dangerous. Making matters worse, hostile autocracies are increasingly

acting in concert in a malevolent axis that features China, Russia, and Iran at

the center, joined by Cuba, North Korea, and others. Protecting democracy

against such forces will take strength, agility, and tenacity. The world’s

liberal democracies must enhance their external defenses and cooperate more

closely to maintain an economic, military, and technological edge that denies

antidemocratic adversaries the power to dominate global politics and undercut

their rivals.

At the same time, as

underscored by the recent electoral gains of extremist populist forces on both

the right and the left in France and Germany, democratic leaders cannot neglect

their internal defenses. Emerging and mature democracies alike need strategies

to counter the siren song of illiberal populism. Even a long-standing liberal

democracy can turn toward autocracy if its government does not deliver

effective policies to combat crime and terrorism, manage national borders,

soothe societal divisions, and ensure broad access to economic opportunity and

security.

In their global

outreach, liberal democracies must push back against authoritarian campaigns of

disinformation and covert influence. They must make bigger and

better-coordinated investments in development assistance to foster economic

growth and the rule of law that make countries partners for democracy rather

than captives of autocracy or failed states. To win the war of ideas, they need

to disseminate democratic values, lessons of success and failure, and sources

of true information.

The possibility of a

democratic transition cannot be written off in any country. Autocracies live in

fear that what happened to seemingly impregnable one-party communist regimes in

the late twentieth century will happen to them. At any time, a leader’s death

or a sudden crisis can open an opportunity to sweep away an entrenched

autocracy. But proponents of democracy can do more than simply wait.

Competitive elections, even when they are not free and fair, are mobilizing

events charged with opportunity for change. When those moments come, they must

be seized not only by voters but also by other democratic countries.

Ahead of an election,

democracies can provide opposition groups with the funding and training they

need to conduct parallel vote tabulations. They can help political parties

mount more substantive and effective campaigns. They can provide technical and

financial assistance to election management bodies. They can help civil society

organizations identify and counter disinformation and foreign interference on

social media. They can send in independent observers during the campaign, the

vote, and the vote count to fortify domestic monitoring efforts. If the

opposition wins and the incumbent is reluctant to step down, democracies may

need to offer concessions to the defeated autocrat in exchange for accepting

the results—and potentially bring withering pressure down on the regime if it

refuses.

When promising

opportunities for democratization arise, as witnessed this summer in Bangladesh

and Venezuela, they should command focused international attention. But the

agencies and networks that support democratic transitions should also keep an

eye trained on elections in the years ahead. In many countries that have edged

away from democracy or have not yet fully secured it, voters will continue to

face critical choices at the ballot box. Elections will provide opportunities

to advance democratic progress in countries such as Armenia and Malaysia; to

reverse democratic backsliding in Botswana, Georgia, India, Indonesia,

Mauritius, Mongolia, the Philippines, and Serbia; to achieve meaningful

democracy in Gambia, Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Thailand; to dislodge

autocracy in countries where the possibility is often dismissed, such as

Zimbabwe; and to someday put countries torn apart by conflict, such as Ethiopia

and Sudan, on a path to peace and political accountability.

Scholars and

policymakers understand what the political scientist Terry Karl once called

“the fallacy of electoralism.” A democratic election is only a beginning.

Without honest and effective governance, a capable state, the rule of law, an

independent judiciary, and a vigilant civil society, democracy will not deliver

the economic growth, physical infrastructure, social services, public health,

human rights, and safety and security that its voters expect. Helping

democratically elected governments gain access to the financing, investment,

training, and direct assistance they need to serve their people effectively

remains a vital task of official aid agencies, such as the U.S. Agency for

International Development, and of private foundations.

After a two-decade

democratic retreat, the tide must now turn. Competitive elections are not the

end of the story, but they provide the most promising and abundant

opportunities to move in a positive direction politically. A concerted strategy

of international engagement to support free elections could blunt the march of

illiberal populism, strengthen civil societies, help restore democratic

vitality in pivotal countries, and yield the largest harvest of democratic

transitions since the global democratic recession began. Once democracy regains

its momentum, even entrenched dictatorships will be under pressure. The

alternative is a continued authoritarian drift toward a world of increasing

polarization, repression, conflict, and violence. A world dominated by China,

Russia, Iran, and lesser autocracies unburdened by concerns for human rights

and the rule of law. A world hostile to the interests and values not just of

the United States but of freedom-loving people everywhere.

For updates click hompage here