By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

As we have seen in part one, survival

and reproduction. Living standards bordered on the subsistence level and scarcely

varied over millennia. We have experienced a dramatic improvement in the

quality of life.

Living standards bordered on the subsistence level and scarcely varied

over millennia. We have experienced a dramatic improvement in the quality of

life.

This desperate mass exodus, in which people not only endanger their

lives but leave behind their families and homeland, and pay considerable sums

they can scarcely afford to human traffickers, is primarily a result of the

immense inequality in living standards across world regions – manifesting as

gaps in human rights, civil liberties, socio-political stability, quality of

education, life expectancy, and earning capacity, as well as, most urgently in

recent years, the prevalence of violent conflict.

This disparity in living conditions is so vast that the reality of life

at one end of the spectrum is difficult to conceive for someone at the other.

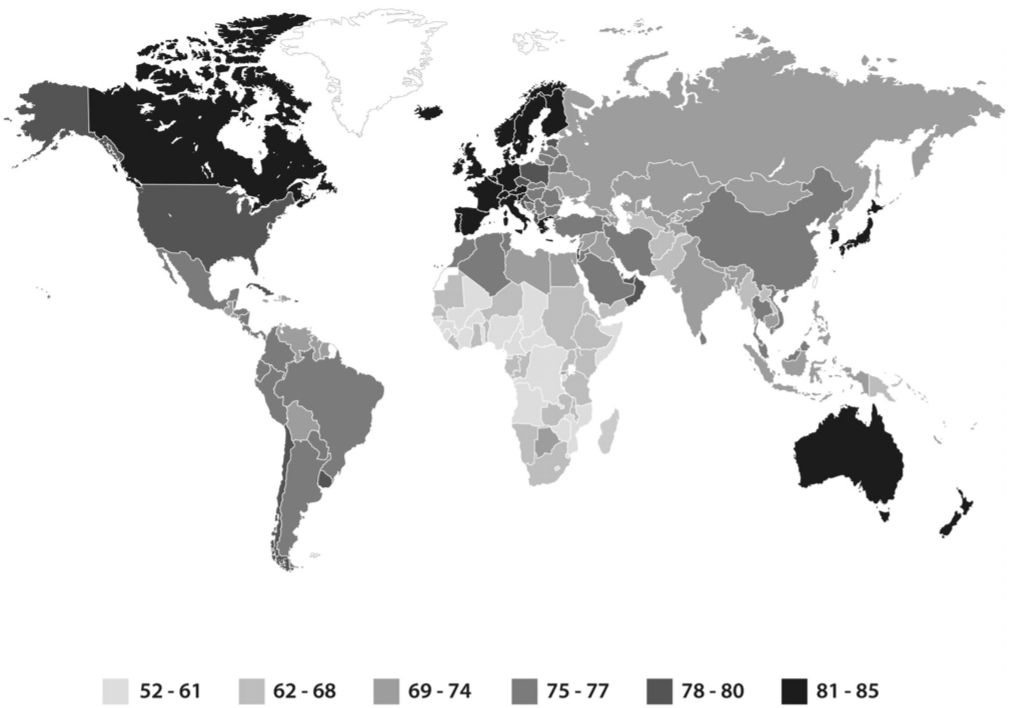

In 2017, in most developed nations, life expectancy exceeded eighty years,

infant mortality was lower than five deaths per 1,000 live births, nearly all

the population had access to electricity, a significant fraction had an

internet connection, and the prevalence of undernourishment was about 2.5

percent. In the least developed nations, by contrast, life expectancy was lower

than sixty-two years, infant mortality rates surpassed sixty deaths per 1,000

births, less than 47 percent of the population had access to electricity, less

than a tenth of 1 percent had an internet connection, and 19.4 percent suffered

from undernourishment.

Equally disconcerting is the gap in living standards across social,

ethnic, and racial lines within societies, manifesting as disparities in

education, income, and health. In 2019, before the impact of Covid-19, in the

world’s most prosperous country, the United States, the life expectancy of

African Americans was 74.7, whereas that of white Americans was 78.8; infant

mortality rates per 1,000 were 10.8 for African Americans and 4.6 for white

Americans; and 26.1 percent of African Americans had a college degree by the

age of twenty-five, in contrast to 41.1 percent of white Americans.

Even so, the gulf in living standards between the richest and the

poorest countries is so much more significant than millions of women and men

risk their lives to reach the developed world.

But why do the citizens of some countries earn significantly more than

the residents of others? This earning gap partly reflects differences in ‘labor

productivity: each hour of work in some world regions produces goods or

services of more excellent value than an equivalent hour of work elsewhere.

Agricultural labor productivity, for instance, varies enormously across

countries. In the United States, agricultural productivity per worker in 2018

is nearly 147 times higher than in Ethiopia, 90 times higher than in Uganda, 77

times higher than in Kenya, 46 times higher than in India, 48 times higher than

in Bolivia, 22 times higher than in China and six times higher than in Brazil.[4]

But again, why do American farmers reap a far bigger harvest than the farmers

of sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia, and most of South America?

The answer should come as no surprise: these differences are primarily

a reflection of the technologies for cultivation and harvesting used in each

country, as well as the skills, education, and training of farmers. For

example, American farmers use tractors, trucks, and combine harvesters, while

farmers in sub-Saharan Africa are more likely to rely on wooden plows often

pulled by oxen. Moreover, American farmers are better trained and can use

genetically modified seeds, advanced fertilizers, and refrigerated

transportation, which may not be feasible or profitable in the developing

world.

Nonetheless, this chain of proximate causes does not shed light on the

roots of the disparity. It simply directs us to a more fundamental question:

Why does the production process in certain countries benefit from more skilled

workers and more sophisticated technologies?

Rusty Tools Previous attempts to understand economic growth, like that

of Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow, focused on the importance of the

accumulation of physical capital – straw baskets, rakes, tractors, and other

machines – to economic growth.

Suppose that a couple harvests enough wheat to bake a few dozen loaves

of bread a week. They use some of these loaves to feed their family and sell

the remainder at the village market. Once they have saved enough, they purchase

a plow, increasing their stock of physical capital, their harvests, and

ultimately the number of loaves of bread they can bake per week. As long as the

couple does not have additional children, this accumulation of capital (the

addition of a plow) will help them increase their per capita income. The impact

of this physical capital accumulation, however, is constrained by the law of

diminishing marginal productivity: as the amount of land and time available to

them is limited, then if that first plow boosts the couple’s output by five loaves

of bread a week, a second plow might only contribute three more loaves, while

the fifth plow may hardly boost productivity at all.

The necessary corollary of this analysis is that only perpetual

improvements in the efficiency of the plow will deliver long-term income growth

for these villagers. Furthermore, acquiring a new plow would spur faster growth

on a poor farm than on a more advanced farm of equal size because this would

likely be the first on the poor farm, whereas it might be the third or the fourth

on the rich one. Thus, a relatively poor farm should grow more quickly than a

more advanced one, and over time the income gap between the poor and the

prosperous farms should narrow.

Solow’s growth model suggests that economic growth cannot be sustained

indefinitely in the absence of technological and scientific progress. Moreover,

it predicts that, with time, income disparities between countries that differ

only in their initial levels of per capita income and capital stocks should

diminish.

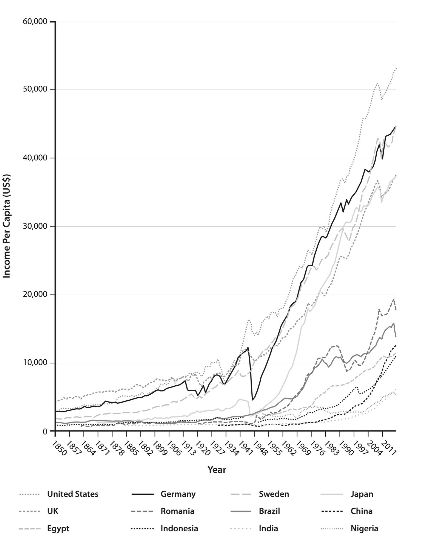

Evolution of Per Capita

Income across Countries, 1850-2016

Imagine a marathon race where the further runners get from the starting

point, the harder each additional step becomes. If one group of runners starts

the race a few minutes earlier than a second, equally talented group of

runners, the first group will keep ahead of the latecomers. Still, the gap

between the two will be narrowing with every stride they take. Analogously, in

countries that differ only in their initial levels of per capita income and

capital stock, those poorer economies that started the race later should

gradually converge with those more prosperous economies that started the race

earlier. Thus the income gaps across these nations should eventually decline.

As the above figure shows, the economies of the developed and

developing nations have not converged. Quite the contrary, in fact: the gaps in

living standards between regions have primarily expanded over the past two

centuries.

What prompted this significant divergence between some countries? And

what are the forces that have prevented some poorer nations from catching up

with richer ones? In the second half of the twentieth century, policymakers

advanced programs to raise the living standards of developing countries based

on the insight that technological progress and the accumulation of physical and

human capital stimulate economic growth. However, inequality across nations

persists to such an extent as to suggest that these policies have had a limited

impact. Too narrow a focus on observable factors on the surface – the

manifested disparities – rather than on the underlying causes that created them

has prevented the design of policies that would help poorer nations overcome

the less visible but more persistent obstacles they face. These forces could

have made a barrier that inhibited investments, education, and the adoption of

new technologies, contributing to uneven development across the globe. It is

these underlying causes and obstacles that we will need to identify if we wish

to decipher the Mystery of Inequality and foster global prosperity.

Trade, Colonialism and

Uneven Development

During the nineteenth century, international trade rose significantly.

The rapid industrialization of north-western Europe triggered it, enabled and fuelled by colonialism and encouraged by reducing trade

barriers and transportation costs. Of the entire world’s output in 1800, only 2

percent was traded internationally. By 1870 that share had risen five-fold to

10 percent; by 1900, it was 17 percent, and by 1913, on the eve of World War I,

it stood at 21 percent. While a significant portion of this commerce took place

between the industrialized societies, developing economies were an important

and growing market for their exports. The patterns that emerged over this

period were unambiguous: north-western European countries were net exporters of

manufactured goods, whereas the exports of Asian, Latin American, and African

economies were overwhelmingly composed of agricultural-based products and raw

materials.

While technological advances during this era could have spawned the

Industrial Revolution without the contribution of the expansion of

international trade, the pace of industrialization and the rate of growth in

Western European nations was intensified by this commerce, as well as by the

exploitation of colonies, their natural resources, their native populations,

and enslaved Africans and their descendants. Likewise, the Atlantic triangular

trade, which was at its height in the preceding centuries, and the growing

trade with Asia and Africa had a major impact on Western European economies.

The trade-in goods itself was highly profitable. Still, it also provided raw

materials such as timber, rubber, and natural cotton for the process of

industrialization, all cheaply produced through enslaved people and forced

labor. Meanwhile, the production in the European colonies of agricultural

products such as wheat, rice, sugar, and tea enabled European nations to

enhance their specialization in the production of industrial goods and benefit

from the expanding markets for their products in the colonies.

The share of national income derived from international trade in the UK

grew significantly: from 10 percent in the 1780s to 26 percent in 1837-45, and

51 percent in 1909-13. Exports were critical for the viability of some sectors,

especially the cotton industry, in which 70 percent of UK output was exported

in the 1870s. Other European economies experienced a similar pattern. The

proportion of national income resulting from foreign trade on the eve of World

War I was 54 percent in France, 40 percent in Sweden, 38 percent in Germany,

and 34 percent in Italy.

This expansion of international trade in the early phases of

industrialization had a significant – and asymmetrical – effect on the

development of industrial and non-industrial economies. In industrial

economies, it encouraged and enhanced specialization in producing industrial

goods that required a relatively highly skilled workforce. The associated rise

in demand for skilled labor in these nations intensified their investment in

human capital and expedited their demographic transition, further stimulating

technological progress and enhancing their comparative advantage in producing

such goods. In non-industrial economies, by contrast, international trade

incentivized specialization in producing relatively low-skilled agricultural

goods and raw materials. The absence of significant demand for educated workers

in these sectors limited the incentive for investment in human capital and thus

delayed their demographic transition, further increasing their relative

abundance of low-skilled labor and enhancing their comparative disadvantage in

the production of ‘skill-intensive’ goods.

Accordingly, globalization and colonization contributed to the

divergence in the wealth of nations in the past two centuries. While in

industrial countries, the gains from trade were directed primarily towards

investment in education and led to growth in income per capita. A more

significant portion of the profits from trade in non-industrial nations was

channeled towards increased fertility and population growth. These forces

persistently affected the distribution of population, skills, and technologies

worldwide, widening the technological and education gaps between industrial and

non-industrial economies and so enhancing rather than diminishing the initial

patterns of comparative advantage. The premise of this argument – that

international trade generated opposing effects on fertility rates and education

levels in developed and less developed economies – is supported by regional and

cross-country analysis based on current and historical data.

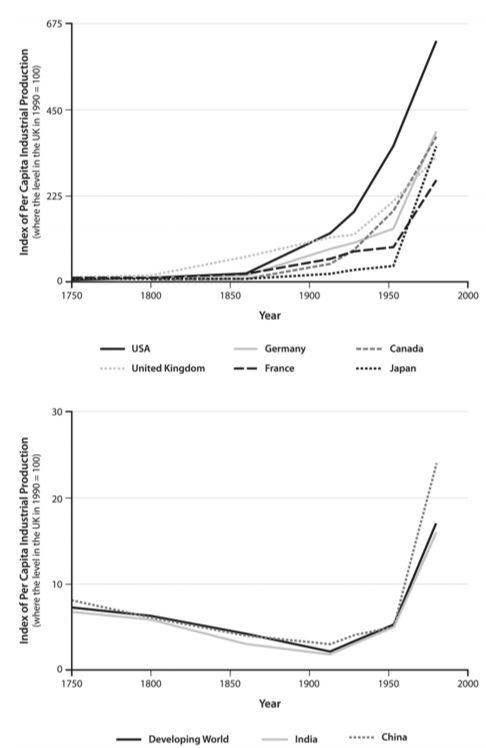

This asymmetric impact of globalization and colonization is also

strikingly evident from the rate of industrializationof

industrialization in developed and developing countries. The level of

industrialization per capita in the United Kingdom rose 50 percent between 1750

and 1800, quadrupled between 1800 and 1860, and nearly doubled between 1860 and

1913. In the United States, it increased four-fold between 1750 and 1860 and

six-fold between 1860 and 1913. A comparable pattern was experienced by

Germany, France, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium and Canada. In contrast,

developing economies experienced a decline in per capita industrialization

during the nineteenth century, and it took nearly two centuries for them to revert

to their initial levels before finally taking off in the second half of the

twentieth century.

The trading relationship between the UK and its colony India

exemplifies this pattern. Between 1813 and 1850, as India experienced a rapid

expansion in its exports and imports, the country gradually transformed from

being an exporter of manufactured products – predominantly textiles – into a

supplier of agricultural goods and raw materials. Trade with the UK was

fundamental in this process. The UK supplied over two-thirds of India’s imports

(primarily manufactured goods) for most of the nineteenth century and was the

market for over a third of its exports.

The effect this had in the UK will by now be familiar. By fostering the

process of industrialization, trade helped contribute to the significant

increase in demand for skilled labor in the second phase of the Industrial

Revolution. The average years of schooling of the male labor force of England,

which did not change significantly until the 1830s, had tripled by the

beginning of the twentieth century. School enrolment at the age of ten

increased from 40 percent in 1870 to nearly 100 percent in 1902. In the 1870s,

the overall fertility rate in the UK started to drop, and in the subsequent

fifty years, it declined from about five children per woman to nearly 2.5. Over

this same period, the economy transitioned into sustained growth in income per

capita at almost 2 percent per year.

The Impact of Globalisation: Industrialisation

and Deindustrialisation across the Globe

In contrast, India experienced a decline in its per capita level of

industrialization. The entrenchment of the agricultural sector in India, for

which education was not essential, contributed to the persistence of widespread

illiteracy well into the twentieth century. In the twentieth century, attempts

to enlarge primary education were hampered by low attendance and high dropout

rates.[19] Despite the gradual spread of education, 72 percent of Indians

beyond fifteen had no schooling in 1960. In the absence of significant human

capital formation, the demographic transition in India was delayed well into

the second half of the twentieth century.

And yet, domination, exploitation, and asymmetric trade patterns during

the colonial age enhanced pre-existing patterns of comparative advantage rather

than generating them in the first place. What accounts for the uneven

development before the colonial period? What allowed some countries to become

colonizers and forced others to become non-industrialized colonized?

To decipher the Mystery of Inequality, we will need to unveil more

deeply rooted factors than the ones identified thus far.

Deep-Rooted Factors

Imagine that one bright morning you pull yourself out of bed,

brew a cup of coffee and while stepping outside to greet the day, discover that

the grass is greener outside your neighbors’ house.

Why is their lawn so lush? A technical reply might be that your

neighbors’ grass reflects light at wavelengths in the green range of the spectrum,

while yours reflects light closer to the yellow range. This explanation, while

perfectly accurate, is not particularly helpful – it gets us no closer to

understanding the root of the matter. A more thorough, less pedantic response

would focus on the differences in the timing, intensity and methods that you

and your neighbors have used in taking care of your lawns: irrigating, mowing,

fertilizing, and applying pesticides.

Nevertheless, these reasons, vital as they may be, still might not

uncover the root causes for your neighbors’ grass being greener. They represent

proximate causes for the visible differences in the quality of the two lawns,

behind which are the underlying reasons that explain why your neighbors

irrigate their lawn more regularly, or why they are more successful at pest

control. If you fail to understand the roles of these deep-rooted factors, your

attempts to emulate your neighbors’ gardening methods, persistent as they may

be, might not yield the dazzling green hue that you desperately crave.

Geographical factors might lie behind the visible differences between

the two lawns – variations in soil quality and exposure to sunlight might

frustrate your efforts to mimic your neighbors’ success. Alternatively, the

differences might reflect underlying cultural factors that reflect the

environment in which they and you were raised and the nature of the education

you received – cultural traits, such as an especially future-oriented mindset,

that drive them to great lavish care and attention on their lawn, watering and

mowing it at the optimal times.

It might be that the two properties are under the jurisdiction of

different municipal authorities. Your local council has imposed a watering ban

to conserve water, while your neighbours are free to

water their lawn to their heart’s content. So it could be an institutional

factor that prevents you from imitating your neighbors’ gardening techniques

and closing the gap between the two lawns. Or it could be a deeper reason,

still, in your respective municipalities, that leads to these institutional

differences, something associated with the very make-up of your neighbors’

community. More homogeneous communities are better positioned to implement

regulations and collective decisions about public investment in irrigation

infrastructure and the eradication of pests. In contrast, more heterogeneous

communities might benefit from the cross-fertilization of diverse, innovative

gardening techniques. In this sense, it could be that population diversity is

the underlying cause of the gap between the two lawns.

Like the differences between the two lawns, the immense disparities in

the wealth of nations are rooted in a chain of causal factors: at the surface

are proximate factors, such as the technological and educational differences

between countries; at the core are the more profound and ultimate factors –

institutions, culture, geography, and population diversity – that lie at the

root of it all. Although it may be challenging to disentangle the impact of

proximate and ultimate factors, the distinction is critical if we understand

how these deep-rooted factors have affected the speed at which the great cogs

of human history have turned and thus governed the pace of economic development

in different places.

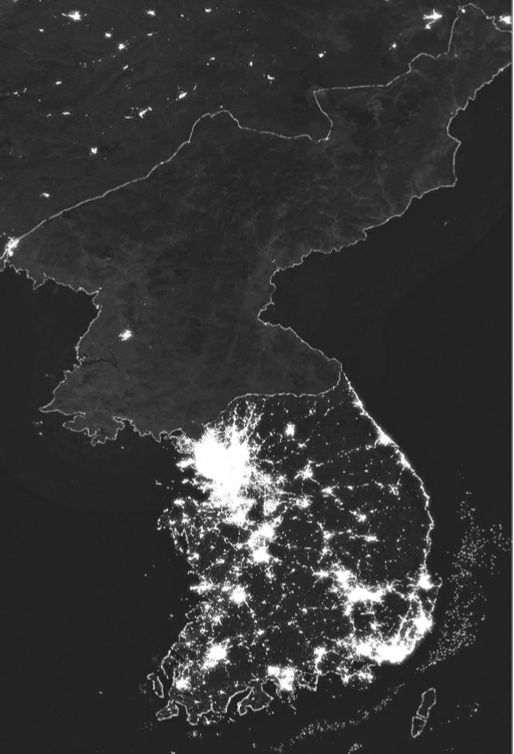

The Korean Peninsula

Satellite imagery of night-time light

In the bottom portion of the picture is the prosperous country of South

Korea, late in the evening: a glittering galaxy of stars radiating the light of

prosperity. South Koreans drive back from work on illuminated roads, spend

their evenings in restaurants, malls, cultural centers flooded with light, or

with their families in their well-lit homes. In contrast, the top segment of

the picture contains one of the poorest countries on Earth – North Korea,

engulfed in darkness. Most North Koreans prepare for an early bedtime in the

gloom of intermittent power outages. Their country does not produce sufficient

energy to keep its electricity grid permanently switched on even in the capital

city, Pyongyang.

The disparities between North and South Korea are neither the result of

geographical or cultural differences nor a reflection of North Koreans’ lack of

knowledge about building and maintaining a functioning electricity grid. For

most of the past millennium, the Korean Peninsula essentially formed a single

social entity, whose inhabitants shared a common language and culture. However,

the partition of Korea after World War II into Soviet and American spheres of

influence brought about divergent political and economic institutions. North

Korea’s poverty and technological underdevelopment – like that of East Germany

before the fall of the Berlin Wall – originates in political and financial

institutions that restricted personal and economic freedoms. Insufficient

constraints on government power, the limited rule of law, insecure property

rights, andrently inefficient central planning hav hindered entrepreneurship and innovation whileraging corruption and fostering stagnation and

poverty. Not surprisingly, South Koreans enjoyed per capita income levels

twenty-four times higher than that of their northern neighbors in 2018 and a

life expectancy eleven years longer in 2020; differences based on other

measures of quality of life are no less drastic.

More than two hundred years ago, the British political economists Adam

Smith and David Ricardo highlighted the importance of specialization and trade

for economic prosperity. Yet, as argued by the Nobel Prize-winning American

economic historian Douglass North, a critical precondition for the existence of

trade is the presence of political and economic institutions, such as binding

and enforceable contracts, that enable and encourage it. Put, if the governing

institutions fail to prevent the violation of agreements – or indeed

racketeering, theft, intimidation, nepotism, or discrimination – trade is

likely to be significantly more complex and the typical gains it conveys less

available.

Societies relied on kinship ties, tribal and ethnic networks, and

informal institutions to facilitate and foster trade in the distant past.

Medieval Maghribi traders, for example, imposed

collective sanctions on those who violated agreements and built on the

specialties between far-flung communities to develop a flourishing transnational

trade across North Africa and beyond.[4] However, as human societies grew more

extensive and more complex, it became necessary to formalize these norms.

Societies that ultimately developed institutions conducive to trade – shared

currencies, property rights protections, and a set of uniformly enforced laws –

would have been better able to foster economic growth, reinforcing the virtuous

cycle between the size and composition of the population and technological

progress. Societies that were late to develop pro-trade institutions would have

lagged.

Throughout human history, the concentration of political and economic

power in the hands of a narrow elite, empowering them to protect their

privileges and preserve existing disparities, has typically held back the tide

of progress. It has stifled free enterprise, prevented significant investment

in education, and suppressed economic growth and development. Scholars refer to

institutions that enable elites to monopolize power and perpetuate inequality

as extractive institutions. In contrast, institutions that decentralize

political power, protect property rights and encourage private enterprise and

social mobility are considered inclusive. In their book Why Nations Fail, the

economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson have demonstrated that

differences in political institutions of this sort have contributed to the gaps

between nations. Extractive institutions have typically hindered human capital

accumulation, entrepreneurship, and technological progress, delaying the

transition from stagnation to long-term economic growth, whereas inclusive

institutions have reinforced these processes.

Yet history suggests that extractive political institutions need not be

detrimental at every stage of economic development. Dictators have occasionally

orchestrated major reforms in response to external threats to their regimes, as

happened in Prussia in the aftermath of its defeat by Napoleon in 1806 and

Japan in the late nineteenth century during the Meiji Restoration. Moreover,

for decades after the partition of the Korean Peninsula, South Korea was a

dictatorship – it did not begin its transition towards democracy until 1987 –

and yet over these three decades, it enjoyed impressive growth while North

Korea remained undeveloped. Both Koreas were ruled initially by autocracies;

their fundamental difference lay in their economic doctrines. The dictators in

Seoul adopted private property protections and far-reaching agrarian reforms

that decentralized political and economic power, while their rivals in

Pyongyang opted for a massive nationalization of private property and land and

centralized decision-making. These early differences provided South Korea with

a significant economic head start over North Korea, long before it became a

democracy. Similarly, the non-democratic regimes that used to rule Chile,

Singapore, and Taiwan – and the ones that still govern China and Vietnam –

successfully spurred long-term economic growth by promoting investment in

infrastructure and human capital, the adoption of advanced technologies, and

the promotion of a market economy.

Nevertheless, while non-inclusive political institutions can coexist

with viable inclusive economic institutions, this has mainly been the exception

rather than the rule – and at critical junctures in human history, the rule

appears to have been a pivotal one. Inclusive institutions might partly explain

why the Industrial Revolution first began in Britain of all places. In

contrast, the presence of extractive institutions may shed light on why some

previously colonized parts of the world continue to lag, decades after their

official liberation from colonial rule.

Institutional Origins of

the British Ascent

Britain’s unprecedented leap forward during the Industrial Revolution

allowed the country to seize control of vast swathes of the planet and build

one of the most powerful empires in history. And yet, for most of human

history, the inhabitants of the British Isles lagged behind their neighbors in

France, the Netherlands, and northern Italy in terms of wealth and education;

Britain was a mere backwater on the edges of Western Europe. British society

was agricultural and feudal; a narrow elite held political and economic power,

and in the early seventeenth century, many sectors of the economy were

aristocratic monopolies by royal decree.[6] Given England's dearth of

competition and free enterprise, these monopolized industries were

spectacularly unproductive in developing new technologies.

Like many other rulers, English monarchs were hostile to technological

change and thwarted their kingdom’s technological progress. One famous and

ironic example is associated with the delayed inception of the British textile

industry. In 1589, Queen Elizabeth I refused to grant the clergyman and

inventor William Lee a patent for his novel knitting machine. She feared that

his invention would harm the local guilds of hand knitters, fostering

unemployment and, therefore, unrest. Rejected by the English queen, Lee

relocated to France, where King Henry IV gladly awarded him the desired patent.

Only several decades later did William Lee’s brother sail back to Britain to

market this cutting-edge technology, which became the cornerstone of the

British textile industry.

However, in the late seventeenth century, Britain’s governing

institutions were radically overhauled. King James II’s efforts to entrench an

absolutist monarchy and his conversion to Roman Catholicism provoked stiff

opposition. The king’s rivals found a savior: William of Orange, stadtholder of

various Protestant counties of the Dutch Republic (and husband of Princess

Mary, the king’s eldest daughter). They urged him to seize power in Britain.

William heeded their call, deposed his father-in-law, and was crowned King

William III of England, Ireland, and Scotland. This coup, known as the Glorious

Revolution because it was considered, somewhat mistakenly, to be associated

with relatively little bloodshed, transformed the balance of political forces

in Britain. As a foreign king without a domestic base of support in England,

William III depended heavily on Parliament in a way that his predecessor had

not.

In 1689, the king gave royal consent to the Bill of Rights, which

abolished the monarch’s powers to suspend parliamentary legislation and raise

taxes and mobilize armies without Parliament’s consent. England became a

constitutional monarchy. Parliament began to represent a relatively wide range

of interests, including those of the rising mercantile class. Britain

established inclusive institutions that protected private property rights,

encouraged private enterprise, and promoted equality of opportunity and

economic growth.

Britain intensified its attempts to abolish monopolies in the aftermath

of the Glorious Revolution. King Charles II had been awarded a monopoly over

the African slave trade, was just one of many companies to lose power.

Parliament also passed new legislation to promote competition in the growing

industrial sector, undermining the economic interests of the aristocracy. In particular,

it reduced taxes on industrial furnaces while raising duties on land, which was

largely owned by the nobility.

These reforms, which were unique to Britain at the time, created

incentives that did not exist elsewhere in Europe. In Spain, for example, the

Crown zealously guarded its control on profits from its transatlantic trade,

often funneling them into funding wars and the consumption of luxury goods. In

Britain, the gains from the transatlantic trade in raw materials, goods, and

enslaved Africans were shared by a broad class of merchants. They were,

therefore primarily invested in capital accumulation and economic development.

These investments laid the foundations for the unprecedented technological

innovations of the Industrial Revolution.

Britain’s financial system also underwent a dramatic metamorphosis at

the time, further enhancing economic development. King William III adopted the

advanced financial institutions of his native Holland, including the stock

exchange, government bonds, and a central bank. Some of these reforms expanded

access to credit for non-aristocratic entrepreneurs and encouraged the English

government to be more disciplined in balancing government expenditure and tax

revenue. Parliament gained stronger powers of oversight over public debt

issuance, and bondholders – those who had lent money to the Crown – won

representation in the decision-making process concerning fiscal and monetary

policies. Britain thus came to enjoy greater credibility in the international

credit market, reducing its borrowing costs compared to other European

kingdoms.

The industrial revolution

Ultimately, the quest for some of the deepest roots of modern-day

prosperity led us further back to where it all began: the initial steps of the

human species out of Africa, tens of thousands of years ago. The degree of

diversity within each society, as determined partly by the course of that

exodus, has had a long-lasting effect on economic prosperity over the entire

course of human history – with those who enjoyed the sweet spot of

innovation-inducing cross-fertilization and social cohesiveness benefiting

most.

In recent decades, the rapid diffusion of development among poorer

countries has promoted the adoption of growth-enhancing cultural and

institutional characteristics in all regions of the world and contributed to

the growth of developing nations. Modern transportation, medical and

information technologies have diminished the adverse effects of geography on

economic development, and the intensification of technological progress has

further enhanced the potential benefits of diversity for prosperity. If these

trends were combined with policies that enabled diverse societies to achieve

greater social cohesion and homogeneous ones to benefit from intellectual cross-pollination,

then we could begin to address contemporary wealth inequalities at their very

roots. Today on Tanna Island, one can find a real

airport; primary schools are available for most children; islanders own mobile

phones; and streams of tourists, attracted by the Mount Yasur

volcano and traditional culture, provide vital revenues to the local economy.

While income per capita in the nation of Vanuatu to which the Island belongs is

still very modest, it has more than doubled in the past two decades. Despite

the long shadow of history, the fate of nations has not been carved in stone.

As the great cogs that have governed the journey of humanity continue to turn,

measures that enhance future orientation, education, and innovation, along with

gender equality, pluralism, and respect for difference, hold the key to

universal prosperity.in England may have been contributed to by even earlier

institutional reforms. In the fourteenth century, the Black Death killed nearly

40 percent of the inhabitants of the British Isles. The resulting scarcity of

agricultural workers increased the serfs’ bargaining power. It forced the

landed aristocracy to raise their tenant farmers’ wages to prevent their

migration from rural areas to the cities. In hindsight, the plague had

delivered a fatal blow to the feudal system, and England’s political

institutions became more inclusive and less extractive. The decentralized

political and economic power encouraged social mobility and allowed a more

significant segment of society to innovate and participate in wealth creation.

In Eastern Europe, by contrast, the existence of a harsher feudal order and

lower rates of urbanization, along with a growing demand for agricultural

output from the West, strengthened the landed aristocracy and its extractive

institutions in the aftermath of the Black Death. In other words, what might

have been insignificant institutional variations between Western and Eastern

Europe before the Black Death led to a major divergence after its outbreak,

placing Western Europe on a radically different growth trajectory from Eastern

Europe.

The relative weakness of the guilds in Britain also contributed to some

of the institutional changes that preceded Britain’s Industrial Revolution. The

guilds, which operated across Europe, were institutions that defended the

interests of their members – skilled artisans engaged in a particular trade.

They often used their monopolistic powers to stifle entrepreneurship and

technological progress. For example, the Scribes Guild in late-fifteenth-century

Paris managed to bar the entry of the city’s first printing press for nearly

twenty years. In 1561, the Red-Metal Turners Guild of Nuremberg pressured the

city council to deter a local coppersmith by Hans Spaichi,

who had invented a superior slide rest lathe, from spreading his invention,

ultimately threatening to jail anyone who dared to adopt his new production

techniques. In 1579, the Danzig city council ordered the inventor of a new

ribbon loom, which threatened traditional ribbon weavers, to be drowned in

secret. And in the early nineteenth century, an angry mob of the Weavers Guild

in France protested against Joseph-Marie Jacquard (1752–1834), the inventor of

an innovative loom operated using a series of punched cards – technology that

would later inspire the programming of the first computers. In contrast, the

British guilds were less powerful than their European counterparts, which may

have been partly a consequence of the rapid and largely unregulated rebuilding

of the City of London in the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1666, as well as

rapid market expansion elsewhere, leading to a greater demand for craftsmen

than the guilds could supply. Their weakness made it easier for Parliament to

protect and enable inventors, allowing British industrialists to adopt new

technology quickly and efficiently.

Modern-day prosperity

Ultimately, the quest for some of the deepest roots of modern-day

prosperity led us further back to where it all began: the initial steps of the

human species out of Africa, tens of thousands of years ago. The degree of

diversity within each society, as determined partly by that exodus, has had a

long-lasting effect on economic prosperity over the entire course of human

history – with those who enjoyed the sweet spot of innovation-inducing

cross-fertilization and social cohesiveness benefiting most.

In recent decades, the rapid diffusion of development among poorer

countries has promoted the adoption of growth-enhancing cultural and

institutional characteristics in all regions of the world and contributed to

the growth of developing nations. Modern transportation, medical and

information technologies have diminished the adverse effects of geography on

economic development. The intensification of technological progress has further

enhanced the potential benefits of diversity for prosperity. Suppose these

trends were combined with policies that enabled diverse societies to achieve

greater social cohesion and homogeneous ones to benefit from intellectual

cross-pollination. In that case, we could begin to address contemporary wealth

inequalities at their very roots. Today on Tanna

Island, one can find an actual airport; primary schools are available for most

children; islanders own mobile phones; and streams of tourists, attracted by

the Mount Yasur volcano and traditional culture,

provide vital revenues to the local economy. While income per capita in the

nation of Vanuatu to which the Island belongs is still very modest, it has more

than doubled in the past two decades. Despite the long shadow of history, the

fate of nations has not been carved in stone. As the great cogs that have

governed humanity's journey continue to turn, measures that enhance future

orientation, education, and innovation, along with gender equality, pluralism,

and respect for difference, hold the key to universal prosperity.

For updates click hompage here