By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Why Did Antony Blinken Went To

Doha?

The region is

suffering from a precipitously brutal coarsening of its politics. Once again,

the time of the assassins and their enablers in the Middle East is upon us.

Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant on Saturday (Nov 11) warned

Lebanon's Hezbollah not to escalate the conflict along the border."Hezbollah

is dragging Lebanon into a war that might happen," Gallant told troops in

a video aired by Israeli television channels. "It is making mistakes and

... those who will pay the price are first and foremost Lebanon's citizens.

What we are doing in Gaza we can do in Beirut."Gallant's

warning came after Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah said that his group

was deploying new types of weapons to hit targets in Israel further affirming

that the front in the south against its foe would remain active.

Elsewhere in the US,

a Jewish school in Montreal is fired upon for the second time this

week. The incident took place only two days after that school and another

Jewish school in Montreal, Canada’s second-largest city, were fired

upon. For Israel and Palestine, the only way to break the cycle of

violence is to understand the difference between justice and vengeance.

Does The Road To Middle East Peace Run Through Doha?

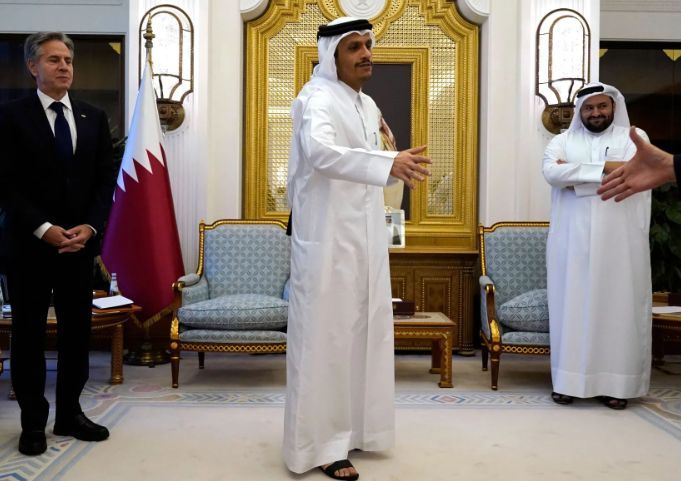

Qatar’s Prime

Minister and Foreign Minister Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani (C) and US

Secretary of State Antony Blinken (L) attend a meeting, in Doha on Oct.13.

Bringing together

Qatar, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to administer postwar

Gaza could weaken Iranian and Russian regional influence.

While the

Israel-Hamas War is raging, Western leaders have a unique opportunity to plan a

wholesale reconfiguration of the chessboard of Middle Eastern politics. Because

there is no purely military outcome that can provide security or prosperity for

either Israelis or Palestinians, failure to seize the diplomatic opportunity

presented by this crisis will make future wars increasingly likely.

Diplomats better

respond to events on the battlefield, but they should also try to shape them.

Israeli leaders have made it clear that they have no novel concept for the day

after and are trying to use the war to destroy Hamas and weaken Iran’s regional

proxies. Their articulated strategy is simply a more drastic form of “mowing

the lawn” and will allow the same regional dynamics to resurface post-war, just

as they have after previous rounds of Israel-Hamas fighting or the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war.

Hamas, Iran, and

Russia do not plan to end the war by securing diplomatic objectives. Their goal

is disorder. They intend to use the war to inflame regional and

global tensions, so as to keep their adversaries divided. At the war’s end, the

absence of a regional solution and a hardening of pre-existing fissures is a

victory for Hamas, Iran, and Russia.Western diplomats

planning for the day after the conflict are thus confronted with a choice: push

to use this war to merely weaken their enemies or seek to reshape the region’s

existing power blocs.

The former would

result in a hardening of the region’s existing three camps:

pro-Iranian/pro-Russian (Hezbollah, Syria, Yemen’s Houthis), those willing

to work with the Muslim Brotherhood (Qatar, Turkey, Western Libya), and those

virulently opposed to the Muslim Brotherhood (United Arab Emirates, Egypt,

Saudi Arabia, Israel, Eastern Libya). The latter could achieve a conceptual

reframing of the region into an axis of Orderers united in their willingness to collaborate to

confront the Disorderers. Western diplomats can

attempt to remove regional drivers of conflict by pulling the existing grouping

of Arab states willing to work with the Muslim Brotherhood (namely Qatar and

Turkey) away from their occasional dalliances with both Iran and destabilizing

Sunni militant movements like Hamas.

People flee following Israeli airstrikes on a

neighborhood in al-Maghazi refugee camp in the central Gaza Strip.

The lynchpin in this

realignment must be Qatar since it occupies the position of pivotal swing state

for the entire Middle Eastern system. Only Qatar can talk with Sunni extremists

and the Ayatollahs, as well as the Saudis, Turks, Israel, and the United States.

This is why all hostage release deals are mediated exclusively through Doha. If

the Qataris can be encouraged to decisively embrace the forces of order,

the region can exit the current conflict poised for stability, and economic

growth, and in a position to evict Iranian proxies from the region.

The role of mature

diplomacy in times like these is to avert further suffering, contain disorder, and seek to push combatants toward the least bad

option. Rather than merely weakening their enemies, Washington and London best

used their convening power to create an Axis of Order. To do so,

they must grasp that the road to regional peace runs through Doha. It is not

only the place of residence of Hamas’s political wing, but Qatar acts as

Hamas’s piggy bank and entrance point to the international financial system. As

such, only Qatar can rein in Hamas, guarantee that a defeated Hamas does not

rise again, and ensure that the Sunni Arab powers are united in confronting

destabilizing Russian and Iranian proxies.

Hamas emerged during

the first intifada to galvanize political Islam in the Palestinian territories

to adopt a rejectionist “resistance” stance toward Israel and abandon the

previous quietist stance that had characterized Muslim Brotherhood activity in

Gaza in the 1970s and early 1980s. Now, thanks to Qatari control of its

purse strings, the Muslim Brotherhood must be urged to return to a quietist

direction throughout the region.

To do so, they must

grasp that the road to regional peace runs through Doha. It is not only the

place of residence of Hamas’s political wing, but Qatar acts as Hamas’s piggy

bank and entrance point to the international financial system. As such, only

Qatar can rein in Hamas, guarantee that a defeated Hamas does not rise again,

and ensure that the Sunni Arab powers are united in confronting

destabilizing Russian and Iranian proxies.

Hamas emerged during the first intifada to

galvanize political Islam in the Palestinian territories to adopt a

rejectionist “resistance” stance toward Israel and abandon the previous

quietist stance that had characterized Muslim Brotherhood activity in Gaza in

the 1970s and early 1980s. Now, thanks to Qatari control of its purse strings,

the Muslim Brotherhood must be urged to return to a quietist direction

throughout the region.

Until now, Emirati

and Qatari funding of opposing political movements in all the post-Arab Spring

states has been a primary driver of the regional mess the world now faces. But

that can—and must—change.

Mature Anglo-American

diplomacy should therefore focus on creating a Qatari, Emirati, Saudi, and

Egyptian condominium to administer post-war Gaza’s foreign affairs,

borders, health care, infrastructure, and education for a period of five

to 10 years while rebuilding, de-Hamasification, and preparations

for elections are undertaken. Lessons from post-conflict states that have held

elections too early, for example, post-Arab Spring Libya or Egypt, should serve

as a warning against a rush to turn things over to the Palestinian Authority

(or another successor government) or to bring about elections too soon. Many on

the Israeli and American right do not trust the Qataris and accuse them of

wishing for Hamas to survive out of ideological affinity and a desire to be

needed as a mediator. That is an outdated reading of Qatari intentions fueled

by a right-wing obsession with punishing states that work with Islamist

movements. In the early post-Arab Spring period,

the Qataris unfortunately funded assorted armed Sunni militants in Egypt,

Libya, Tunisia, and Gaza. Some of their foreign policy choices during that

period did not look so wise in hindsight. Now is the time for the West to allow

the Qataris to turn the page.

Qatar And Hamas

Among the questions

that keep coming in the nonstop discussion of Hamas’s spectacular and bloody

attack on Israel last week is this: “What is the story with Qatar?” Not long

after the attack, when the violence perpetrated on Israeli civilians was

becoming clear, the Qatari Ministry of Foreign Affairs released a statement blaming Israel for Hamas’s assault.

Given the scale of

the killing (about 1,400 people have been killed in Israel), the statement was

shocking. Saudi Arabia—which has developed a relationship with Israel that, at

least before Hamas’s attack, was becoming more and more open—also pointed the

finger at Israel, but its statement was more nuanced and less pugnacious in tone. And

both stood in sharp contrast to the reaction of the United Arab Emirates—Qatar’s rival and

Israel’s closest partner in the Arab world—which called Hamas’s attack “a

serious and grave escalation” and said it was “appalled by reports that Israeli

civilians have been abducted as hostages from their homes.”

Then, last Monday,

Reuters reported that Qatari mediators were in talks with both

Hamas and Israeli officials to negotiate the release of the women and children

that the Palestinian militant group took hostage during its assault. It was a

slim piece of good news since war broke out on Oct. 7. It seemed that despite

what his foreign ministry had said a few days earlier, Qatari Emir Tamim bin

Hamad Al Thani was doing whatever he could to be constructive, befitting his

country’s role as a U.S. partner and major non-NATO ally. The Qataris may not

be successful, but whatever the outcome, they deserve credit for trying.

Still, much of

Washington held the hosannas for Tamim. The muted response to Doha’s effort on

behalf of Israeli families reflects the diverging views of Qatar within the

foreign policy community. To some, the Qataris are regional arsonists; to

others, they are the fire department.

It is possible for

two things to be true at once, of course. But Washington’s conflicting views of

Qatar a Shiite country have less to do with any strategic genius on the part of

Qatar’s leaders than the constraints of U.S.-Middle East policy.

From one perspective,

it is clear that Qatar pulls more than its weight when

it comes to helping Washington. In the mid-1990s, when relations between the

United States and Saudi Arabia grew testy and large numbers of U.S. forces were

no longer welcome in the kingdom, the Qataris swung open the doors to the

United States and gave the U.S. Central Command a shiny new forward operating

base in the Persian Gulf. The Qatari Emiri Air Force owns the base, which is

called Al Udeid, and served as the place from which

the Pentagon ran the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as well as countless

counterterrorism operations. As of a few years ago, it was home to as many as

10,000 U.S. service personnel, a large number, but down considerably from its

peaks during the 2010s.

Of course, Emir Hamad

bin Khalifah Al Thani —the current emir’s father—was not totally altruistic in

doing this. Bestowing a base on U.S. forces was a way to invest Washington in

his continued rule, which was the result of a coup in which he overthrew his

father. The large number of U.S. troops in Qatar was a form of protection

against vengeful family members, along with neighbors such as Saudi Arabia who

did not like Doha’s independence streak.

Al Udeid was important in August 2021, when U.S. forces

withdrew from Afghanistan and brought thousands of Afghans with them. Others in

the region—notably the Emiratis—also did their part, but Qatar was the first

destination for many refugees. When it came to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine the

following winter, Qatar’s leader—unlike other U.S. partners, including

Israel—was unequivocal in his condemnation of the Kremlin.

When the Russians

suspended a U.N.- and Turkey-brokered deal that facilitated the exports of

Ukrainian agricultural products that are critical for global food supplies, the

Qataris worked with Turkey and the Russians to find a solution. The emir’s

diplomats were not successful, but they showed up and tried to make something

happen. And while they have evinced little public interest in normalizing ties

with Israel, Doha stations a diplomat in Gaza—with Israel’s blessing—to

distribute aid to the poorest Gazans.

The Qataris are not

just helpful to the United States abroad, but also at home. Before the war

between Israel and Hamas began, I received an invitation from the Qatari

Embassy inviting me to its fifth annual gala in support of the Autism Society

of America. And when Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans in 2005, the Qataris

pledged $100 million to help Louisianans in need.

Yet as positive and

constructive as the Qataris have been in some areas, they have also been a

troublesome partner. The same year that construction on Al Udeid

Air Base began, the Qataris launched Al Jazeera.

At first, the

state-owned TV network seemed to be a breath of fresh air, broadcasting actual

news and commentary (except about Qatar) in a region where state media fare was

little more than regime talking points and the tick-tock of a given leader’s

day. In time, however, it became clear that many of the producers, journalists,

and commentators on Al Jazeera’s flagship Arabic network had a yen for

Islamism, antisemitism, and anti-Americanism.

When it comes to the

Palestinians, the Qataris are true to their principles in support of

Palestinian justice and rights, and as noted above, can be constructive, but

the effort to win the release of Israeli hostages in Gaza seems to be the

exception that proves the rule.

For updates click hompage here