By Eric

Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Early Islam in its wider context

On

November 15-16 an International Conference on Quran will take

place in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. And while renewed discussions no doubt will take

place about manuscripts

found in 2015 appear to confirm the tradition that Muhammad’s

immediate successor, Abu Bakr (632–634 CE), ordered the creation of an

authoritative text of the Prophet’s visions, see

also.

According to Islamic

tradition, a uniform consonantal skeleton (rasm) of the Qur'an

was first compiled

into a book format by Abd al-Malik ibn Hishām. As the Islamic Empire began to grow, and

differing recitations were heard in far-flung areas, the 'rasm', or consonantal

skeleton of the Quran was recompiled for uniformity in recitation (r. 644–656

CE).

The Qurʾān yields little concrete biographical information

about the Islamic Prophet: it addresses an individual “messenger of God,” whom

a number of verses call Muhammad (e.g., 3:144), and speaks of a pilgrimage

sanctuary that is associated with the “valley of Mecca” and the Kaʿbah (e.g., 2:124–129, 5:97, 48:24–25). Certain verses

assume that Muhammad and his followers dwell at a settlement called al-madīnah (“the town”) or Yathrib (e.g., 33:13, 60) after

having previously been ousted by their unbelieving foes, presumably from the

Meccan sanctuary (e.g., 2:191). Other passages mention military encounters

between Muhammad’s followers and the unbelievers.

Most of the

biographical information that the Islamic tradition preserves about Muhammad

occurs outside the Qurʾān, in the so-called sīrah (Arabic: “biography”) literature. Arguably the

single most important work in the genre is Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq’s

(died 767–768) Kitāb al-maghāzī (“Book of [the Prophet’s] Military

Expeditions”). Ibn Isḥāq’s original book

was not his own composition but rather a compilation of autonomous reports

about specific events that took place during the life of Muhammad and also

prior to it, which Ibn Isḥāq arranged into what he

deemed to be their correct chronological order and to which he added his own

comments.

What the Koran

however does tell us is that Muhammad advocated the reconciliation of people

whose faith descended from God’s revelation to Abraham. It tells us that he

preached a powerful message of moral probity, that he delivered a potent vision

of heaven as the future home of the faithful, of hell for enemies of the true

faith who refused to be reconciled to Muhammad’s truth, and of the world’s end.

What he did not do is predict the sudden takeover of the Roman and Persian

empires, the extension of the community of his followers, within a century, to

lands running from Spain to India.

According to a recent

article by Marco Demichelis, the meaning and elaboration of Jihad

(just-sacred war) hold an important place in Islamic history and thought. On

the far side of its spiritual meanings, the term has been historically and previously

associated with the Arab Believers’ conquest of the 7th–8th centuries CE.

However, the main idea of this contribution is to develop the “sacralization of

war” as a relevant facet that was previously elaborated by the Arab Christian

(pro-Byzantine) clans of the north of the Arabian Peninsula and the Levant and

secondarily by the Arab confederation of Muhammad’s believers. From the

beginning of Muhammad’s hijra (622), the interconnection between the Medinan

clans that supported the Prophet with those settled in the northwest of the

Hijaz is particularly interesting in relation to a couple of aspects: their

trade collaboration and the impact of the belligerent attitude of the

pro-Byzantine Arab Christian forces in the framing of the early concept of a

Jihad. This analysis aimed to clarify the possibility that the early

“sacralization of war” in the proto-Islamic narrative had a Christian Arab

origin related to a previous refinement in the Christian milieu.1

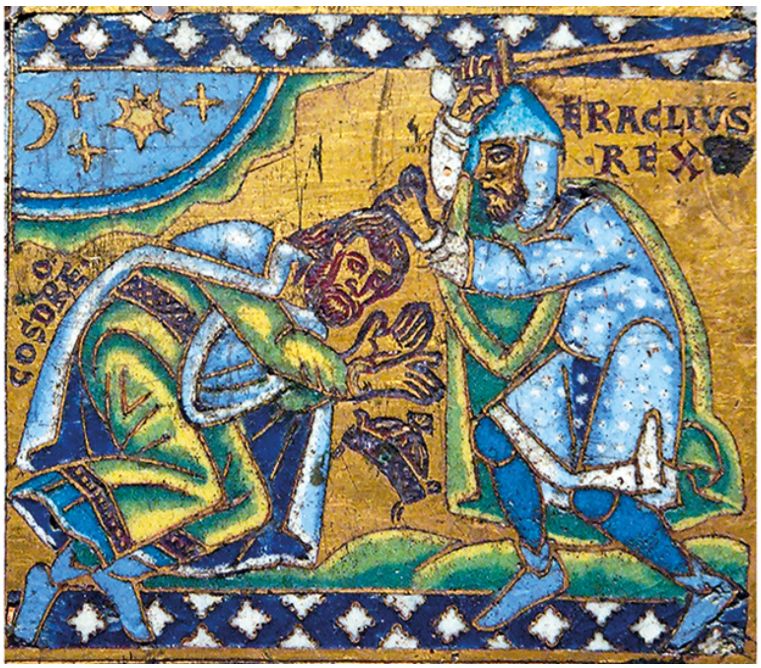

Rome and Persia at War

The rise of the new

Arab state means that we must also pause for a moment to contemplate the

phenomenon which is often referred to, since Montesquieu’s book On the

Greatness and Decline of the Romans and Edward Gibbon’s masterful Decline and

Fall of the Roman Empire, both composed in the eighteenth century, as the “Fall

of the Roman Empire.” The result of the Arab conquests in the seventh century

was that the Roman Empire declined but did not fall. It ceased to be a

Mediterranean entity and would henceforth be limited to portions of what is now

Turkey, modern Greece, and, occasionally, Bulgaria. We conventionally refer to

this reduced entity as the Byzantine state, a name derived from the ancient

name of the city that had become Constantinople. The rulers at Constantinople,

who called themselves “Roman,” would have been surprised by this terminology.

According

to Rome and Persia at War Imperial Competition and Contact, 193–363 CE by

Peter Edwell however, the military conflict between Rome and Sasanian

Persia was at a level and depth not seen mostly during the Parthian period. At

the same time, contact between the two empires increased markedly and

contributed in part to an increased level of conflict.2

The Sassanid

emperor Shāpūr I had invaded Roman Mesopotamia and Syria in about

240: the Romans fought back, defeating the Persians at Resaena

in 243. That the Romans now sued for peace owed more to grubby politics than a

military necessity: Philip the Arab, who had assassinated Gordian III and seized the imperial throne for himself,

needed a chance to secure his position without outside pressure.

However, Shāpūr continued his depredations in the eastern parts of

the Roman Empire, taking a number of territories. As emperor from 253, Valerian

resolved to win these back. According to the Naqsh-e

Rustam inscription, his army was 70,000 strong, and at first, it seems to have

made real headway. By the time the men reached Edessa (in what is now

southeastern Turkey, near the Syrian border), they were beginning to

flag, however. Valerian decided that his troops should hole up in the city, to

which Shāpūr immediately laid siege. An outbreak of

plague here cut a swath through what was soon a severely weakened Roman army.

When Valerian led a deputation to Shāpūr’s camp to

negotiate a settlement, he was captured with his staff and taken back to Persia

as a prisoner. Valerian died in captivity.

Stressing the decline

of Rome has the unfortunate tendency to obscure the fact that the fates of Rome

and Persia were linked. The two empires controlled the major agricultural

regions of Egypt on the one side and Iraq on the other and were surrounded by a

ring of tribal societies whose welfare depended upon access to the products

controlled by these empires. The true impact of the Arab conquest was to bring

this system to an end, replacing it with an extensive new political system

based on states sharing a common religious identity that stretched from central

Asia, ultimately to southern Spain. This powerful Islamic world was flanked by

tribal societies in Asia or relatively weak polities whose most important

common feature was their adherence to some form of Christianity in

Europe.

Others have argued

that because the concept of the “Fall of Rome” doesn’t reflect the complexity

of the situation, many scholars have now substituted the term “Late Antiquity”

to encompass the period from roughly the reign of Constantine until the period

in which the new world order stabilized in the seventh to eighth centuries CE.

This has the advantage of stressing change as the dominant aspect of this

period, of allowing for the ascent as well as descent, and for the agents of

change is neither Roman nor Persian.

The spread of

Muhammad’s message into the world of Late Antiquity stemmed in part from the

exceptional talent of Muhammad’s followers, and the exceptional incompetence of

the leadership of both the Roman and Persian empires. The failure of the

governing class in both the Roman and Persian empires arose from the heady

combination of economic failure, natural disaster, bigotry, and bone-headed

refusal to recognize new realities imposed by changed economic circumstances.

Traditional government incapacitated itself prior to confronting the threat

that emerged from tribes united by Muhammad’s vision.

The failure of

traditional government is insufficient in and of itself to explain the success

of the new order or even the existence of what would become the new order. It

took nearly fifty years after the disruption of the old world order in the 630s

for a new regime to emerge that was able to unite the areas that had suddenly

fallen under Arab control around a coherent vision for the future. The success

of the Arab conquest stemmed not only from the failures of Persian and Roman

governments but also from the ability of ‘Abd al-Malik, a successor to the

leaders who won the initial victories, to bureaucratize Muhammad’s teachings.

In so doing, ‘Abd al-Malik provided the ethical basis of a new government.

The last great war of

antiquity’ started when the Shah of Persia, Khusro II, decided that the

assassination of an unpopular emperor in a palace coup in Constantinople gave

him the excuse and the window he needed to try to put right a punitive

settlement that had been imposed on Persia a decade earlier. According to James

Howard-Johnston, it was a miscalculation that changed the world, writes the

author, the start of a war whose consequences were so profound that it serves

as ‘the final episode in classical history.

The bubonic plague in its wider context

There was also the

bubonic plague that arrived in the Mediterranean and spread rapidly throughout

Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. The bacterium came from Central

Africa; the first outbreak was at Alexandria in Egypt, where trade from the

south and east was funneled into the broader economy.

The effect on

Alexandria was catastrophic. Then, in the spring of 542, ships from the city

carried the infected rodents to Syria, Asia Minor, and Constantinople, where

the pestilence ran its course for four months. Contemporaries interpreted the

outbreak as both the vengeance of God and as a play date for demons. A

historian of the period wrote that many people saw apparitions in human form

which struck them; another says that some demons appeared in the form of monks.

Doctors knew not what to do; they had never seen the disease, and those who

recovered did so for no obvious cause. The death toll was horrendous; five or

ten thousand people perished in a single day. The total number of deaths at

Constantinople may have reached 300,000, while in one town on the Egyptian

border all but eight people were found dead. People were seen to totter and

fall in the streets; merchants or customers might be suddenly overcome in the

midst of a transaction; a house was filled with nothing but the dead, twenty

bodies in all; infants wailed as their mothers died. At Constantinople the

authorities filled the tombs around the city, digging up all the places where

they could lay the dead and finally filling the towers in the defensive walls.

A plague victim recalled how he was afflicted with the swellings, and how later

the disease took his wife, many of his children, and relatives, servants, and

tenants. For some, he said, the first symptoms were in the head, making the

eyes bloodshot and the face was swollen; the symptoms then descended to the

throat. For others, there was a violent stomach disorder, while for those whose

lymph nodes swelled up there was a violent fever, then death, if it would come,

by the third day.

Yet the plague

probably didn't

wipe out the Roman Empire and half the world's population. What it did was

that the plague devastated the economy, signs of expansion in various areas

came to an end in the middle of the sixth century. An immediate effect of the

plague was also to short-circuit an effort on the part of the Roman government

in Constantinople to rebuild effective control in the western Mediterranean. In

the previous century, a collection of Germanic successor states had arisen in

territory once controlled by Rome in North Africa, Spain, France, and Britain.

Rome had regained control of North Africa in the 530s and had ousted the

Germanic regime in Italy a few years later, but it had not yet built a stable

regime of its own to replace the one it had unseated. That would now not

happen. When the empress Theodora, in many ways the brains behind the

government, died of cancer in 548, the imperial regime would blunder from

failure to failure for the rest of the reign of her husband, Justinian, who

didn’t die until 565. Most significantly, Rome lost effective control over the

central Balkans where a new, Bulgarian, state was developing. Justinian’s

successor Justin was of very limited ability, losing control of most of Italy

and faring badly in a war with Persia before his abdication in 578. His two

successors, Tiberius and Maurice, stabilized the situation, but what was really

needed was peace, and peace required strength that Rome no longer had.

It is in the Balkans

that the economic transition away from the Roman imperial economy first becomes

obvious. Politically, the plague-weakened, over-committed empire progressively

lost control in the half-century after Theodora’s death. The most serious problems

were connected with the arrival of a new group of Turkic peoples, the Avars, from Ukraine into the region north of the Danube. In

567 the Avars assisted one Germanic tribe, the

Lombards, in destroying their long-term enemies, the Gepids

(the safety of the Roman frontier had depended upon the Roman ability to play

these two groups off against each other). The Lombards, however, recognizing

that they were likely to be the next target for Avar expansion, headed south

into Italy to continue the by now seemingly endless struggle for control of the

peninsula. There was worse to come. Even before the Avars

arrived, Slavic tribes had been moving into the area north of the mouth of the

Danube. Once the Avars established themselves, the

Slavs tended to join them to raid Roman territory. On their own the Slavs, who

were rather badly organized, were not a great threat. Linked with the Avars, they constituted a force that required powerful

Roman armies to control, and those armies were soon stretched too thin. In 582

the Avars launched a series of devastating raids that

culminated in the capture of Sirmium, the long-time

bastion of Roman rule on the upper Danube.

As chaos encompassed

the frontier, local landowners, feeling betrayed by an imperial regime that

could not keep hostile neighbors under control, began to look to their own

protection. And they started eating differently, preferring legumes and millet

to winter-sown grains. They had nothing now to exchange with other parts of the

empire, which in turn lost markets to which they could previously have shipped

surplus. Cities in the imperial core of western Turkey showed signs of decline

even as the plague-ravaged economies of Syria and Egypt stabilized. Stabilizing

does not, however, mean fully recovering. The urban decline had the collateral

effect of lowering the empire’s tax receipts, and that had the further effect

of weakening the military.

The fight and split in reference to the Holy

Trinity

The Roman Empire’s

problems were not just economic. There was also a serious split over the proper

way to understand the relationship between the members of the Holy Trinity. In

451 a council was summoned at Chalcedon (across the Bosporus from Constantinople)

to produce a new creed, stating that Christ had two natures, human and divine,

that became one after “he was made man.” This statement was anathema to many

bishops in Syria and Egypt, who believed that Jesus had but one, divine,

nature. The split between the two sides worsened with the passage of time,

dividing communities throughout the eastern provinces against themselves, and

some of Persia’s numerous Christians against those within the empire. The faith

which Constantine had used to explain his great success and justify his new

order now became a divisive force.

1. Marco Demichelis,

Arab Christian Confederations and Muhammad’s Believers: On the Origins of

Jihad, ORCID Centre for Interreligious Studies, Pontifical Gregorian

University, 00187 Rome, Italy Academic Editor: Brannon Wheeler Religions 2021,

12(9),710; https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090710 Peter Edwell, Rome

and Persia at War Imperial Competition and Contact, 193–363 CE, 2021.

For updates click homepage here