By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

How East and West Met

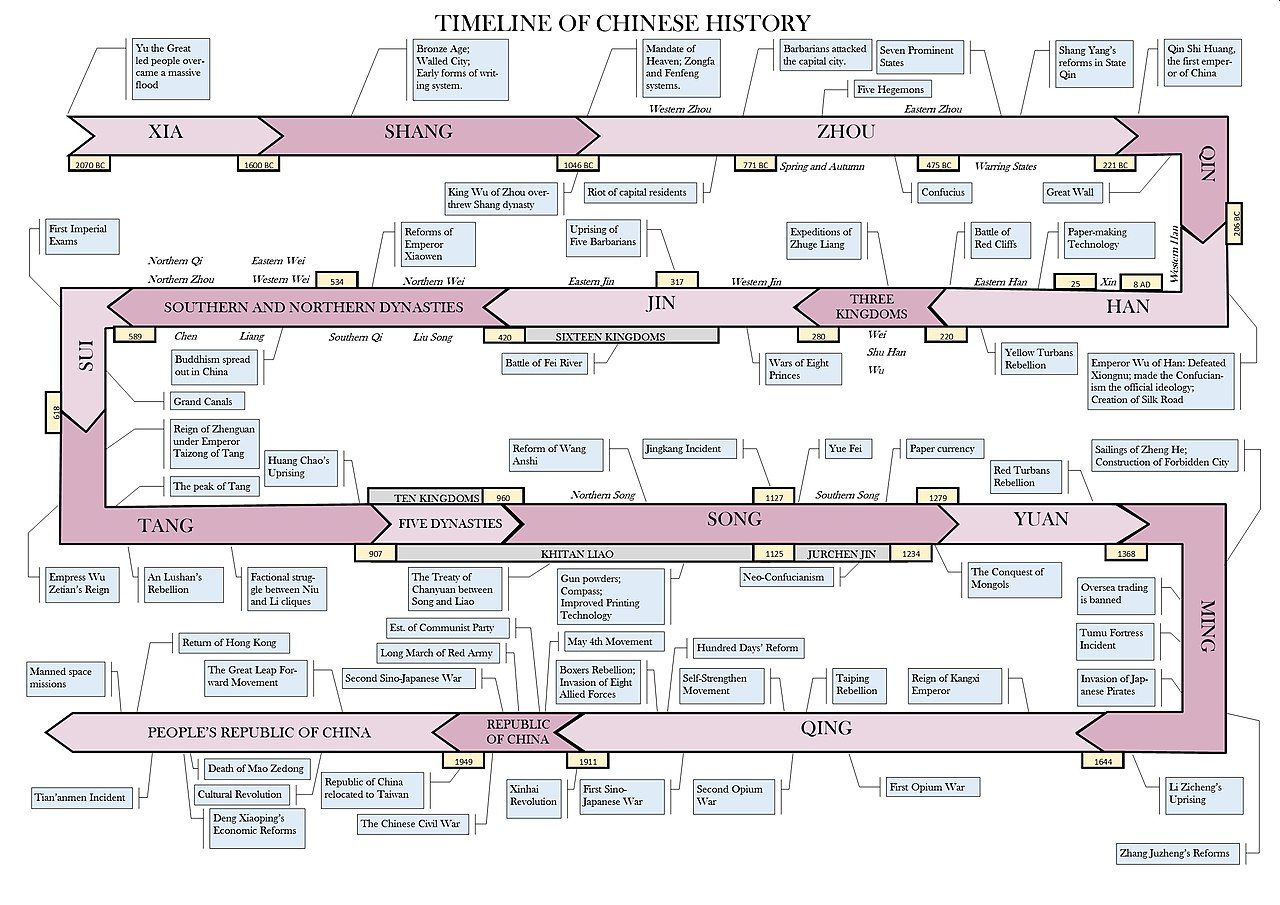

As we early on indicated in the Western

imagination, China's history has been inextricably linked to the notion of

"empire." But in fact, more than a millennium of Chinese history

passed before anything resembling an empire ever existed. For centuries, six

separate states battled for military supremacy, until in 221 B.C. the Qin

dynasty defeated the last of its rivals and unified the country. Military

conquest is only part of the imperial story, however.

Chinese state and

society underwent a profound change in the Former Han period. During the early

years of the Former Han the exact nature of state and society was by no means

clear, but by the end of this period, the broad outlines of the imperial system

had been established for all subsequent Chinese history. The Ch'in Dynasty had

indicated one direction, but its collapse had revived many of those elements

present at the end of the third century B.C. which could logically have

developed into a limited open society.

The defining

characteristics of the Chinese empire-and, indeed, of all, empires-were its

large scale and the diversity of its peoples. While all of China's inhabitants

have retroactively become "Chinese" today, this term is anachronistic

for the pre-imperial period. The peoples of that time would have been known as

the Qin, Qi, Chu, or by the name of one of the other Warring States, or as the

inhabitants of a particular region (for example, the people "within the

mountain passes"). The Qin's conquests united these groups politically in

the third century B.C., but distinct regional cultures and

"temperaments" survived. Such regional variations were not an

inconvenient fact of life but, rather, became essential to an empire that

justified itself by making just this kind of hierarchical distinction between

the universal, superior culture of the imperial center and the limited,

particular cultures of regions and localities. This fundamental distinction

manifested itself in political service, religion, literature, and many other

aspects of Chinese life. And following the Qin, the Han empire would come as we

will see below. The most important change brought about by the Qin

conquest, however, was the universal use of a single non-alphabetic script. By

standardizing written communication among groups that did not speak mutually

intelligible tongues, this innovation bound together all the regions of the

empire and allowed the establishment of a state-sanctioned literary canon. Thus

Keith Buchanan explained that "The real history of China is not so much

the history of the rise and fall of great dynasties as the history of the

gradual occupation of the Chinese earth by untold generations of farming

folk."1

In later periods even

areas that did not become part of modern China, Japan, and Vietnam shared

significant elements of culture through their use of a common written script.

Eventually, a common literary culture linked all those engaged in, or aspiring

to, state service. In later centuries literacy would permeate lower levels of

society, through Chinese theater, popular fiction, and simplified manuals of

instruction.

In the centuries

following the Qin conquest, the gradual demilitarization of both peasant and

urban populations and the delegation of military service to marginal elements

of society reversed an earlier trend among the competing states which had

extended military service throughout the peasantry. In 31. A.D. universal

military service was formally abolished, not to reappear until after the end of

the last empire in 1911. In place of a mobilized peasantry, military service

was provided by non Chinese tribesmen, who

were particularly skilled in the forms of warfare used at the frontier, and by

convicts or other violent elements of the population, who were transported from

the interior to the major zones of military action at the outskirts of the

empire. This demilitarization of the interior blocked the establishment of

local powers that could challenge the empire but also led to a recurrent

pattern in which alien peoples conquered and ruled China.

Finally,

"empire" as it developed in early China depended on the emergence of

a new social elite-great families throughout the realm who combined landlordism

and trade with political office-holding. Those families dominated local society

through their wealth, which they invested primarily in land, and their ability

to mobilize large numbers of kin and dependents. In the classical period, law

and custom divided inherited property among sons, and therefore landed wealth

was subject to constant dispersal. Even large estates (although no estates in

this period were large by Western standards) devolved into a multitude of small

plots within a few generations. In order to reproduce their wealth over time,

families were obliged to find sources of income outside agriculture. Trade and

money lending were vital occupations among the gentry, but the greatest source

of wealth was imperial office-holding.

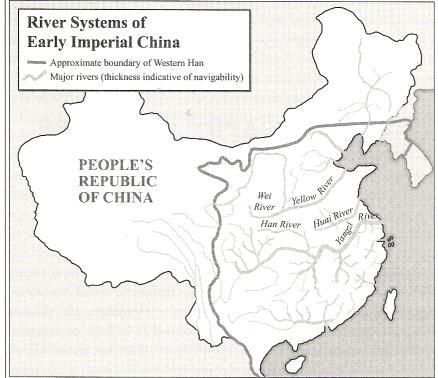

Like all of Chinese

history, also the geography of the early empires is a tale of the country's

many distinct regions. The state created by the Qin dynasty was not the modern

China familiar from our maps. The western third of contemporary China (modern Xinjiang

and Tibet) was an alien world unknown to the Qin and the early Han. Modern

Inner Mongolia and Manchuria also lay outside their frontiers, as did the

southwestern regions of modern Yunnan and Guizhou. While the modern southeast

quadrant (Fujian, Guangdong, and Guangxi) was militarily occupied, it also

remained outside the Chinese cultural sphere. The China of the early imperial

period, and of much of its later history, consisted of the drainage basins of

the Yellow River and the Yangzi. This area comprised all of the land that was

flat enough and wet enough to be suitable for agriculture, and thus defined the

historical limits of the Chinese heartland.

In the Roman Empire,

it was cheaper to ship grain or wine all the way from one end of the

Mediterranean Sea to the other than to transport it just a hundred miles

overland by wagon. Regions without water links were not integrated in the

Mediterranean economy. The same was true of China. Prior to the construction of

railroads in the nineteenth century, carrying grain more than a hundred miles

by pack animal cost more than producing the grain itself. Except for luxury

goods such as spices, silks, or gems, where small amounts produced large

profits, hauling goods overland was prohibitively expensive. And a lack of good

natural harbors in north China made trade up and down the coast uneconomical.

Consequently, almost all bulk trade relied on inland waterways. But even this

mode of transportation had its limitations. Both of the major rivers-the Yellow

River and the Yangzi-flowed from west to east, with no navigable water links

between them. No natural intersecting lines of transport moved north and south.

Over time, as the bottom of the channel gradually rose, the river overflowed

its banks. Dikes were built ever higher to prevent flooding, and in some places

the river started to flow above the surrounding countryside. Today, in a

stretch of about 1,100 miles, the Yellow River moles along yards above

the plain. But dikes do not control silting, and floods continued to occur on

an ever larger scale. On more than 1,500 occasions during the history of

imperial China the Yellow River burst its dikes, destroying farmland, killing

villagers, and earning its description as "China's sorrow." But under

the Qin and Han empires, the Yellow River was the core of Chinese civilization,

home to around 90 percent of the population. It was separated by mountains and

hills into a northwestern region (modern Gansu and northern Shaanxi), the

central loess highlands (modern Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Western Henan), and the

alluvial floodplain (modern Henan, southern Hebei, Shandong, northern Anhui,

and northern Jiangsu). The Yangzi drainage basin, still a frontier region in

this period, was also naturally divided into three regions: the mountain-ringed

Min River basin (modern Sichuan), the middle Yangzi (Hubei, Hunan, and

Jiangxi), and the lower Yangzi (Zhejiang, southern Anhui, and Jiangsu).

The Qin state's

conquests of its neighbors and the unified empire that emerged were built on a

foundation of reforms that Shang Yang, a minister from the state of Wey,

carried out in the years following 359 B.C. His radical, thoroughgoing

transformations of Qin military and civil life grew out of practices that were

first pioneered in Qi and in Jin and its successors. Internecine wars

among the Zhou nobility following the monarchy's loss of power and the eastward

shift of the capital in 770 B.C. had put pressure on Qi and Jin to

increase the size of their armies. Gradually these states extended military

service from the nobility and its followers to the entire population of the

capital, and then on to certain segments of the rural population. Under Shang

Yang's adaptation of these practices, Qin peasants who served in the army were

rewarded with land that their individual households could hold and work and on

which they paid taxes. But there were severe punishments as well as rewards.

When the fall of his

last rival left the king of Qin master of the civilized world, he and his court

were fully aware of the unprecedented nature of their achievement. As one

courtier remarked, they had surpassed the greatest feats of the legendary sages

of antiquity. And now they would set about enacting visionary programs designed

to institutionalize a new era in human history, the era of total unity.

Yet, the Qin dynasty

collapsed within two decades because it did not change enough. Despite its

proclamations of making a new start in a world utterly transformed, the Qin

carried forward the fundamental institutions of the Warring State era, seeking

to rule a unified realm with the techniques they had used to conquer it. The

Qin's grandiose visions of transformation failed to confront the extensive

changes that the end of permanent warfare had brought about. It fell to the

Han, who took over the realm after the Qin dynasty's defeat, to carry out the

major institutional programs and cultural innovations that gave form to the

vision of world empire.

Although more than

nine-tenths of the population worked on the land during the Qin and Han

empires, little was written about peasants. Elites preferred the color and

excitement of cities and the allure of power at court. Bound to the soil, rural

life smacked of the brutish and vulgar. However, Shen Nong, the so-called

Divine Farmer, figured in the Han pantheon. Credited with the invention of

agriculture, he was the patron sage of a Warring States tradition that insisted

all men should grow their own food. An early Han philosophical compendium

Master of Huainan (Huainanzi) quotes him as a

law-giver: "Therefore the law of Shen Nong says, 'If in the prime of life,

a man does not plow, someone in the world will go hungry. If in the prime of

life, a woman does not weave, someone in the world will be cold.' Therefore he himself

plowed with his own hands, and his wife herself wove, to set an example to the

world."

Some writers adapted

this doctrine to support the Qin regime, which was dependent on rural

households' productivity and suspicious of merchants' wealth, and it was

carried forward into the Han. Farming was even incorporated into a rarely

performed ritual in which Han emperors initiated the agricultural season with

three pushes of a plow in a special field. Major officials then took a turn, to

show through simulated labor the court's interest in agriculture. The empress

did her part by engaging in ceremonial weaving for the feast of the First

Sericulturist.

The limits of the Qin

Empire roughly defined the enduring borders of the Chinese people and their

culture. Although the empire was sometimes extended into the northern steppes,

Central Asia, southern Manchuria, Korea, and continental southeast Asia, these

expansions were generally brief. The peoples of these regions remained beyond

Chinese control until the final, non Chinese Qing

dynasty. The people surrounding China can be divided into two groups. To the

north and west lay nomadic societies that lived on grasslands and formed states

radically different from the Chinese model. Except for the oasis city-states of

Central Asia, these regions would remain outside the Chinese cultural sphere.

By contrast, the watery regions of the south and southeast, as well as the

highland plateaus of the southwest, were progressively settled by Chinese

emigrants. There, and in the northeast, sedentary agrarian states would

gradually adopt Chinese forms of writing and state organization, but these

developments had scarcely begun during the early imperial dynasties.

Born Liu Ch'e in 156 B.C.,

Wu-ti was reportedly the eleventh son of Han emperor

Ching-ti and not in line to ascend the throne.

It was through the Han expansion that China made its

first contacts with peoples outside of the traditional Chinese sphere, as its

emissaries reached as far as Parthia (in modem Iran), China developed its

earliest firsthand knowledge and understanding of other- particularly-expansion

Western-cultural worlds. Second, the triumphant military expeditions implanted

the Middle Kingdom idea firmly and visibly in the Chinese worldview of

international relations, in which China was the center and superpower of the world,

and other peoples and countries were referred to only in tributary and

subordinate terms. This replaced the conception of multination equality that

had gradually formed through the pre-expansion of Han-Hsiung-nu

relations from 200 to 133 B.C. Third, through the martial merits of Emperor Wu,

empire building and its accompanying military expansion became in Imperial

China a permanent part of the dual criteria of the historical judgment of an

emperor: wen-chih (civil and cultural merit)

and wu-kung (martial achievements).

Without wu-kung, wen-chih was

not enough to make an emperor stand out in history. Many emperors became

prisoners of such a concept and unwisely tried too hard to fit the pattern,

only to ruin themselves and their empires. Furthermore, in institutional

realms, Wuti's many new political organizations, intellectual

and economic innovations, and legal measures, which were all instituted to meet

needs created by military expansion, remained as permanent features of

traditional China, and some even survive today.

In dynastic terms,

Emperor Wu's reign reached a peak in the Western Han. His long military

expeditions and colonial efforts eventually exhausted the nation's economic

resources and manpower, and hence affected, and even broke in some cases, the

established political, economic, and intellectual balance and stability of the

Western Han empire. In long-range terms, it was Wuti's great

expansion that eventually precipitated the decline of the Western Han dynasty.

Han Wu-ti and his new empire have been a highly controversial

topic in Chinese history. On the one hand, many regarded the emperor as a model

ruler and empire builder. But others considered him the personification of

pretentiousness, ruthlessness, and selfishness, and his great empire a project

of self-destruction and a symbol of the misery of the common people.

This controversy dates even to Wu-ti's own time.

In 89 B.C., he issued an edict deploring his expansionist adventures and

expressing his regret about the sufferings they had inflicted on the people.

All of this has increased the complexity and variations in historical

discourses on the origins, development, and consequences of Emperor Wu's new

empire.

The high degree of centralization in the Han

government contributed to the internal stability necessary for the Han Court to

mobilize large military campaigns. From the time Kao-ti ascended

the imperial throne in 202 to the end of his reign in 195 B.C., practically

every year the Han Court was threatened by the rebellions of feudal states.

These states controlled almost two-thirds of the Han territory, and some of

them were extremely large and powerful. The Ch'i kingdom controlled

six provinces (chun) with seventy-three districts (hsien), the Tai kingdom three provinces with fifty-three

districts, the Ch'u kingdom three provinces with thirty-six

districts, and the Wu kingdom three provinces with fifty-three districts. These

kingdoms were virtually independent in every aspect. Furthermore, they had

their royal courts and governing systems, independent economic resources and

financial institutions, and, most important, independent armies. The Wu, for

example, had an army of over five hundred thousand men, with an additional

three hundred thousand from its ally Nan-yueh in

the south. Moreover, the powerful generals who helped Uu Pang

(the later Kao-ti) create the empire also constituted

a threat to the court. The reign of Emperor Hui (Uu Ying)

lasted only seven years (195-188 B.C.). The emperor was young, and

Empress Lii held the real power. Even

though this was a period of consolidation of Han rule, the struggle for power

between the Lii clan and the imperial

family (Uu clan) was already under way. In the

next period, under the reign of Empress Lii (187-180

B.C.), this struggle reached its zenith. The empress ruled through members of

her own family; the important members of the imperial clan were in their

distant kingdoms and marquisates. At the same time, the threat of the powerful

generals continued. The court was in a state of great tension. After

Empress Lii's death in 180 B.C., the whole Lii clan

was massacred by a joint force of members of the imperial family and Kaotsu's old loyal henchmen. Emperor Wen (Wen-ti, Liu Heng, 180-157 B.C.) was enthroned, although he had

not been the heir apparent. He was the oldest living son of Kao-tsu and had been the king of Tai (mainly Shansi)

before being chosen emperor. Moreover, as he stated in an edict in the first

year of his reign, at this time the king of Ch'u (Uu Chiao,

Kiangsu) was his youngest uncle, the king of Wu (Uu P'i,

Kiangsu, and Chekiang) was his brother (actually a cousin), and the king

of Huai-nan (Liu Chang, Anhui) was his younger brother. There were other strong

kingdoms of The Uu Clan (羽家 Ūke) (is one of

the Hyou Gates). The clan's name translates to

"Feathers". the Uu clan in

outlying regions of the empire. At one time, he was even reluctant to accept

the throne under these circumstances. The emperor was not in a position to deal

effectively with these feudal states, and tensions certainly existed between

the states and the Imperial Court. Some of these kings disregarded the orders

of the court and plotted a rebellion against the emperor. At least two feudal

kings openly rebelled against him: the king of Chi-pei in

177 B.C. and the king of Huai-nan in 175 B.C. By the beginning of the

reign of Emperor Ching, the conflict between the feudal kings and the Han Court

had reached a climax. While the imperial government was preparing to curtail

the power of the various feudal kings, a rebellion of seven of the strongest

kingdoms-Wu, Ch'u, Chiao-hsi, Chiao-tung, Tzu-ch'uan, Chi-nan, and Chao-broke out in 154 B.C. It was the

most serious revolt during the former Han period. It lasted several months and

was finally suppressed by the imperial forces under the generals

Chou Ya-fu and Tou Ying, which killed more than 130,000 rebel

troops. The kings of the seven rebel states all were forced to commit suicide

or killed by the imperial forces.

It is clear that

during the period from 202 to 154 B.C. the Han empire was not politically

stable. The court was frequently threatened by various unruly groups and

rebellions. It was impossible for the court to concentrate on external problems

or launch all-out military campaigns against the Hsiung-nu and others

while the constant threat of internal rebellions continued. For instance,

during the reign of Emperor Wen the Hsiung-nu menace became more serious,

and so did the threat of the feudal kings. In 177 B.C., the Hsiung-nu's Worthy

(Wise) King of the Right invaded the regions south of the Yellow River and

northern Pei-ti (in modem Ninghsia). But when Emperor Wen went to Tai (in northern

Hopei) and prepared to lead a campaign against the Hsiung-nu the king of

Chi-pei (in southern Shantung) immediately took

the opportunity afforded by the emperor's absence from the capital to start a

rebellion. The emperor was forced to call off the expedition and order his

forces to attack the rebellious king.

After 154 B.C., the feudal kingdoms were never again a

major threat to the Han Court. From this year to the last quarter of the second

century B.C., the Han Court used various means to render the existence of

feudal kingdoms merely nominal, and its effort to eliminate more feudal

kingdoms continued: three more were destroyed early in Wu-ti's reign.

After the Rebellion of the Seven Kingdoms, Emperor Ching also undertook special

measures to change the structure of the feudal kingdoms. First, he took away

the independence of their political system. He eliminated the position of yu-shih tai-fu (the imperial secretary or deputy chancellor

in the royal court) in 147 B.C. and degraded the status of the

chancellor in the royal court by changing its title from ch' enghsiang to hsiang (chief adviser) in 145 B.C. The next

year he changed the governing system in the kingdoms by drastically reducing

the number of officials and assigning new titles to them, showing their

inferior status compared to officials in the central government. To further

eliminate any possible regional division, the emperor even ordered in 142 B.C.

all marquises (ch'e-hou) not to assume their posts in

their respective marquisates. Second, starting in 147 B.C. the emperor

gradually eliminated the feudal kings' economic independence by nationalizing

mintage and the currency system and imposing a monopoly on various essential

material goods. Third, Emperor Ching broadened the base of entrance into

officialdom to include the common people in order to reduce the monopoly of

official positions by the hereditary aristocrats and their wealthy followers.

In 142 B.C., he reduced the long-established financial requirement for official

appointments by 60 percent, from one hundred thousand to forty thousand in cash

(copper coins). In the same year, he decreed that merchants, who were usually

required to register with the government and were the allies and supporters of

the ambitious feudal kings, be prohibited to serve as officials either by merit

or by open purchase. With all these aggressive measures, the possibility of any

successful challenge to the Imperial Court by the feudal kingdoms and their

local supporters was almost completely eradicated under Emperor Ching.

At the same time,

there were conscious efforts to transfer the administrative power from regular

cabinet members to officials close to the emperor, as symbolized by the rise of

the Inner Court (Nei-t'ing or Nei-ch'ao) to usurp the power of the Chancellery and the

Imperial Secretariat. All these measures plus other formal and informal means

of control and inspection brought fundamental changes in the power structure

and distribution of the Han government. The power of the emperor and the

centralization of the government reached their highest degree during the reign

of Emperor Wu. The long struggle for power between such powerful pressure

groups as the imperial in-laws, the imperial family, and those who were

instrumental in the founding of the empire was finally ended during Wu-ti's reign.

Basic changes in

relationship between the central political power and local society also took

place. Before Emperor Wu, the monarchy was without real and close ties to local

society. Kao-ti, founder of the dynasty, followed a

Ch'in practice of moving the rich local elites and the powerful aristocratic

families, which numbered more than one hundred thousand, from the eastern

regions to the Kuan-chung area (Shensi)

under the direct supervision of the central government so that these people

could not induce tension and disturbances with their wealth and influence. At

the same time, families of his meritorious assistants, who were given

high-ranking positions in the government, were moved to the district where his

tomb was constructed, which was hence named Ch'angling.

Following this latter practice, succeeding rulers moved the families of

officials with an annual salary of 2,000 bushels (shih) of grain and local rich

elites, merchants and stalwarts to districts and towns of their tombs (ling-i), located in the capital area and constructed in their

own times. This measure evidently combined the control of certain potentially

dangerous segments of population-in the case of local elites and stalwarts-and

the traditional system of hostage taking-in the case of high-ranking

officials. All of these practices, however, were not strictly enforced on

a large scale until Wu-ti's time. 's Moreover,

even if they were, they would have achieved only one goal-social stability

through population control-and that alone would not be effective enough to

enable the central government to fully mobilize the massive manpower and

economic resources needed for long and large-scale military expeditions against

the Hsiung-nu.

Two basic measures

were undertaken in the early period of Wu-ti's long

reign. The first was the reinforcement of the practice of population migration.

In 139 B.C., the second year of his reign, the emperor first established his

tomb in Mou County, which was later called Mou-ling. Next year,

for the sake of positive encouragement, he granted to those who moved

to Mou-ling two hundred thousand ch'ien in

cash to each household and 200 mu (or mou, Han acres) of land. In 127

B.C., two years after his new military offensives had begun, Emperor Wu ordered

that stalwarts from provinces and kingdoms and those whose property was worth 3

million ch'ien in cash or more be moved

to Mouling. The purpose was to increase the

population of the capital area and at the same time prevent the spread of evil

and vicious elements in the provinces and kingdoms. The second measure that

Emperor Wu undertook to exert thorough control over local conditions was to

gradually incorporate leaders of local pressure groups not moved to the capital

area into governmental institutions as bureaucrats. This policy was usually

carried out by the provincial governors. But their efforts were directed and

controlled by the central government.

Another measure in

the imperial government's quest for internal political and social control and

stability was the use of "harsh officials" (k'u-li).

These officials believed in strict legal order as the basis of good government,

in the use of cruel measures against unlawful conduct, and in the equality of

all people-commoners, noblemen, and officials before the law. They held

positions of various types and ranks, such as governor (t'ai-shou

or chun-shou), regional military commandant (tu-wei or chun-wei, chief

commandant), capital commandant (chung-wei), prefect

or governor of the capital (nei-shih), palace

counselor (chung ta-fu), commandant of justice (t'ing-wei), general, clerks in offices of different levels,

and others. They often employed tricky and vicious investigators to look for

unlawful activities. Their main targets of investigation and persecution were

members of the rich elite, the nobility, corrupt officials, stalwarts and men

of evil influence, and racketeers and vicious merchants. With only one

exception in Kao-ti's time, officials with such

political and legal philosophies did not gain influence and prominence until

late in Ching-ti's reign after the Rebellion of

the Seven Kingdoms was crushed in 154 B.C. Emperor Ching was the first Han

ruler to send an official with a harsh reputation to a specific region. In

about 151-150 B.C., the famous Chih Tu was appointed governor of

Chi-nan (in central Shantung) to restrain the Hsien clan. This clan consisted

of over three hundred households and was so notorious for its power and

lawlessness that none of the two thousand officials in the area could do

anything to control it. Chi executed the worst offenders of the Hsien clan,

along with their families, and the rest were overwhelmed with fear. After a

year or so under Chih T u's rule, no one in the province dared even

to pick up belongings that had been dropped on the streets and roads. Other

harsh officials operated in much the same way and at times employed even

harsher measures. Among the people they arrested, prosecuted, and executed in

the provinces and kingdoms, as well as in the capital area, were court ladies,

feudal kings, high-ranking officials, local elites, rich merchants, and

commoners. Such officials became more dominant early in Wu-ti's reign.

They reached the highest echelon of the bureaucracy, and their measures became

even more cruel. The governor of Tinghsiang (in

southern Suiyuan) executed four hundred people

in one day. The governor of Ho-nei (eastern

Honan) executed over one thousand families. Their blood is said to have flowed

over ten Ii (Han miles). In the inquest of

conspiracy for rebellion conducted by the feudal kings of Huai-nan (mainly

Anhui), Heng-shan (in Anhui), and Chiang-tu (central Kiangsu), Chang T'ang-the

most influential harsh official of early Han times in charge of investigations

and judgments. He put to death tens of thousands, at times merely on

circumstantial evidence. These officials became so notorious that they were

given such nicknames as Vicious Hawk, Vicious Killer, and the like.

Furthermore, in 130

B.G Chao Yii and Chang Tang, two of the most notorious and

influential harsh officials at the time, were empowered by Emperor Wu to draw

up various new statutes and ordinances. Among these were the laws that anyone

who knowingly allowed a criminal act to go unreported was as guilty as the

criminal and that officials could be prosecuted for the offenses of their

inferiors or superiors in the same bureau. From this time on, the laws became

more complicated, and they were applied with increasing strictness. This was a

pronounced departure from earlier Han practice, which in general stressed

simpler laws and lenient applications. In the earlier reigns of Emperors Kao

and Hui and Empress Lii, as recently discovered

Han era documents show, there were only twenty-eight sets of statutes and

ordinances and several cases and precedents for reference and comparison. The

principal legal philosophy was "following the established tradition."20

The clear intent of this change was to impose strict political and social order

using harsh legal institutions and enforcement. Small wonder, then, that of the

fifteen notorious harsh officials of Former Han times whose biographies appear

in the Shih-chi (Historical Records) and Han-shu (History

of the Former Han Dynasty), ten flourished in Wu-ti's time.

All were extremely influential in decision-making at the highest level, and a

majority of them were instrumental in the formulation of the most important new

political and economic measures undertaken during Wu-ti's reign.

During the seven

years of the Ch'in-Han transition from 208 to 202 B.C., the main force of

production in the economy, the population of able bodies, was drastically

reduced because of the continuing war destruction and carnage. There were at

least eighty large-scale battles and over one hundred fifty of lesser scale.

However, the casualties in each of these bloody conflicts ranged from several

thousand to tens of thousands and even hundreds of thousands. In 207 B.C., for

example, over two hundred thousand Ch'in soldiers were buried alive by the

rebel leader Hsiang Yii (232-202 B.C.) in Hsin-an (east of

modern Mien-ch'ih in western Honan). Overall,

the Chinese population at the beginning of the Han dynasty was reduced to less

than one-half of the former Ch'in figure of 28 million by the end of the

dynasty. In many regions, the loss was even greater. Chii-ni District (in Hopei), for example, had only

one-sixth of the Ch'in era population left, down from thirty thousand

households to five thousand. The large cities generally, retained only 20 to 30

percent of their former populations due to war deaths and flight. The

great T'ang historian Tu Yu (A.D. 735-812)

estimated that the population of the Han dynasty at its founding was less than

one-third of the population of China in the Warring States period

(404-222 B.c.). The modern scholar Liang Ch'i-ch'ao (1873-1929) estimated the Han population in

Emperor Kao-tsu's time at only about 5 or 6

million, but more recently others have estimated it to have been in the range

of 8.8 to 18 million; my estimate is 12 to 16 million.

The founders of the Han took special measures to

revitalize the bleak economic and social conditions. The government first

instituted a general policy of economic relaxation and reduction of

governmental spending. The theory was that government should interfere in the

people's lives as little as possible. This was intended to correct the Ch'in

policy of working the people so hard in public works and military expeditions

that they eventually rebelled. At the same time, the Han Court also initiated

various measures for economic recovery in different realms of concern. During

the early Former Han, industrial and commercial growth was noticeable. But Han

industry and commerce did not begin their full development in the first three

reigns, 202-180 B.C., of the new dynasty, since the primary concern of the Han

leaders then was full recovery of the agricultural sector. As it was in the

Ch'in dynasty, the main economic concern of the Han founders was

agriculturalism (nung-pen), with commerce and

industry being regarded as "nonessential" economic pursuits (mo-yeh). During the reigns of Emperors Wen and Ching,

180-141 B.C., commerce and industry gradually achieved significant growth, as

the empire's agricultural production had reached a very high level, population

had increased by four times, and living standards (consumption of goods) had

risen significantly. On average, the minimum annual rate of business profits

was 20 percent and higher. The profits of certain industries and businesses

were so huge that later in the next reign, Han Wu-ti's time,

they were channeled into a well-organized new system

of government monopolies to finance the large-scale military

campaigns and eliminate the economic threat to the imperial government posed by

the tremendous wealth of the industrialists and merchants.

There were, according

to Su-ma Ch'ien (145-86 B.C.), forty-six notable types of

commodities of great value-major sources of industrial and commercial wealth-in

market towns and commercial metropolises, and twenty-two of these were produced

through industrial processes of varying degrees of sophistication. Regional

specialization emerged and with it the rise of prosperous interregional trade.

Major industrial enterprises were those of iron, salt, and textiles. The

centers of the textile and clothing industries (silks, silken fabrics, textiles

made of vegetable fibers, and so on) were mainly in Ch'i and Lu (modern

Shantung), Ch'en-liu (in modern Honan), and Shu (in modern Szechwan).

Lin-tzu (Lin-tse) of Ch'i and Hsiang-i of Ch'en-liu were

the two largest centers. Lin-tse was famous for garments and Hsiang-i for fine embroideries. The specialty of

Shu was hemp cloth. Information on the size of these industries in early Former

Han times is not available. But in 48 B.C. each of the three government garment

offices (San-fu) in Ch'i alone generally employed two to three thousand men.

Together with the fact that textiles were a major source of industrial and

commercial wealth, this leads us to assume that a

large pre-expansion textile factory could easily have employed over a

thousand men.

The iron and salt

industries were spread over various regions of the empire, with the largest

centers located in what are modern Shantung, Szechwan,' Kiangsu, Chekiang,

Anhui, and Hopei. From 120 to 110 B.C., the Han government reorganized its

system of salt and iron monopolies. It established special offices for

supervision and management in areas where salt and iron production and profits

were concentrated. In early Han times, there were forty iron offices in

forty chun (provinces) and kuo (feudal kingdoms), and thirty-eight salt offices

in thirty chun and kuo.

Excluding regions that were acquired during Wu-ti's expansion,

forty-five iron offices and thirty-one salt offices were in Han regions of

the pre-expansion period. These regions most likely were centers, in

some cases potential centers of salt and iron production in the pre-expansion

period. The chun and kuo where these Han offices were located, together

with their modern geographical locations. The wide geographical range of salt

and iron production is clearly shown in the information on the total

workforce of salt and iron laborers in the early Han period is not available.

But certain sources indicate that salt and iron magnates often employed more

than a thousand men to manufacture salt and process iron.

Kung Yii (123-43 B.C.) observed in 44 B.C. that the various iron

offices employed an annual work force of over one hundred thousand men, mainly

slaves, to gather iron and copper. It seems that the salt and iron monopoly

implemented in the years 120-110 B.C. was mainly a new attempt to control these

businesses, not a rapid expansion of the existing enterprises. Judging from our

examination of salt and iron offices, about 88 percent of the production

facilities of salt and iron probably existed in the preexpansion period.

If this is the case, then very likely the total annual work force of salt and

iron laborers in the early Former Han was around eighty-eight thousand men.

Salt and iron

businesses were evidently the most profitable enterprises in early Former Han

times. They produced such wealthy and powerful families as the Cho and Cheng of

Shu, the K'ung of Wan (in modern Honan),

and the Ping of Ts'ao (in modern Shantung),

all in the iron enterprise; and the Tiao Hsien of Ch'i in the salt enterprise.

The Chos and Chengs grew

so rich that they each owned a thousand young slaves. Their pleasures in

possessing lands and in fishing, archery, and hunting were comparable to those

of great feudal lords. The K'ung family's

fortune reached several thousand catties of gold, and its head resembled the

young men of princely rank in his behavior, disposition, and activities. The

wealth of the Ping family amounted to 100 million in cash. The Tiao Hsien's

wealth grew to several tens of millions in cash. Needless to say, all of these

families engaged in diverse trading and other commercial activities and

employed every possible means-including lending money, skillful use of slaves,

and political contacts with feudal lords, provincial governors, and prime

ministers of feudal kingdoms-to increase their fortunes. Their wealth and power

exerted great influence on the lifestyles and thinking of people in various

walks of life. The traders in Nan-yang (modem Hopei) all imitated the K'ung family's lordly and openhanded ways. In Tsou and

Lu (in modem Shantung), many people abandoned scholarly pursuits and, following

the model of the Ping family, turned to the quest for profits. Various feudal

states, particularly Wu in the south and Chao (in Hopei) in the north engaged

in the production of iron and salt for huge profits and at times became the

largest producers of these commodities. The tremendous financial strength

derived from iron and salt production enabled these states to threaten the

central government and invite it to take them over.

Copper, the source of

coins, was another profitable industry. It usually went with iron manufacture.

A considerable number of the iron manufacturers also engaged in copper mining

and casting. Shu and Tan-yang (in modern Anhui) and part of the Wu

kingdom (the lower Yangtze Valley), among others, were the well-known

copper-producing regions. At the time of the emperors Wen and Ching (180-141

B.C.), the two most productive copper mines were located in the mountains in

Yen-tao of Shu (modem lung-ching of Szechwan)

and Ch'angshan of Y ii-chang (modem

An-chi of Chekiang). The former was granted to the high official Teng Tung by

Emperor Wen; the latter was in the territory of the king of Wu (Uu P'i, 213-154 B.C.). Both Teng and the king of Wu

minted coins from copper mined from the two mountains by tremendous numbers of

workers. The result was that the coins of Wu and of Teng spread all over the

empire. Teng accumulated wealth that exceeded that of a vassal king. For the

king of Wu, the mintage of coins, together with his salt enterprise, produced

so much revenue that he not only dispensed with taxation but was economically

confident enough to start a rebellion against the imperial government.

But Han expansionism

would also become their downfall, because the Han needed nomads to join the

army, yet they were never fully incorporated into the military hierarchy.

Instead, the Han government relied on the standing frontier commands to keep

them under control. As more and more tribes moved inside the frontiers, this

burden proved too great for the relatively small armies in the frontier camps.

Loyalty was also weak among the convicts and professionals who spent their

lives at the frontier and were linked to the Han state only through the person

of their commander. Another reason for the failure of the Eastern Han army in

the second century was its success in the first. Just as the armies of the

Warring States and early Western Han had been designed to fight Sinitic rivals,

so those of the Eastern Han had been aimed at the northern Xiongnu. With their defeat, many of the "inner

barbarians" who had helped the Han in the first century turned against it.

The Southern Xiongnu, Wuhuan,

and Xianbei lost their chief motive for

submission to the Han, as well as their chief source of bonuses for military

service. So the Wuhuan and Southern Xiongnu turned increasingly to internal pillage for

income, while the Xianbei replaced

the Xiongnu as the chief external threat.

To the west, the problem was even more severe, for this area suffered through

the disastrous Qiang wars.

Every army is

intended to fight a certain type of war or counter a particular kind of threat.

The entire Eastern Han defense faced north, providing a screen against

small-scale raids and a warning in case of invasions. Its large cavalry forces

were assembled for offensive expeditions against a united foe with substantial

armies. Such dispositions were of little use against the Qiang, located to

the west beyond the Han's border defenses. These nomads lacked any over arching political order and did not form large

confederacies. The consequences of any defeat were thus limited, and victories,

however small, soon led to major rebellions as scattered groups assembled under

a successful leader. For the same reasons, peace agreements with

the Qiang could not last for long. Moreover, scattered groups

of Qiang lived throughout the western and northwestern territories,

as well as beyond the frontier. There was no clear geographic boundary between

the Qiang and the Han, and under the Eastern Han

the Qiang were resettled in the old capital region. The only defense

against such an adversary was to move Han farmers and soldiers into the

provinces, so that no settlements were left exposed to low-level attacks and

the Qiang could be absorbed into the Han economy and polity.

But whenever the Han

attempted such a policy, it ended in failure. In 61 B.C. Zhao Chongguo propose founding military colonies in the

west (Honan), Ho-nei (Honan), Chi-nan

(Shantung), T'ai-shan (Shantung), and Shu

and Kuang-Han (Szechwan). In addition, shipbuilding, weaponry, and lumber

were profitable industries, particularly in regions such as Lu-chiang, Nan (Hupei), and Shu. Animal husbandry was an

important enterprise in northern and northwestern border territories. Pottery

and lacquerware also were prosperous industries in certain regions.

With these commercial

and industrial developments, the cities rapidly expanded. In Wu-ti's time, there were twenty Han cities with

populations ranging from 50,000 to 650,000 people, and sixty cities of 20,000

to 56,000. The two largest cities in population were Ch'ang-an, the

imperial capital built only in Hui-ti's reign

(especially in 192-189 B.C.), and Lin-tzu (in Shantung); the former had a

population over 500,000 in a walled city of 13.5 square miles, and the latter

had 650,000 in a walled city of 9.31 square miles. The next five largest were

Yuan (in Nan-yang, Honan), with 4°0,000; Ch'eng-tu (in Chengtu, Szechwan), with 380,000; Han-tan (Han-tan, Hopei),

with 27°,000; La-yang (Loyang, Honan), with 260,000; and Lu (Ch'ii-fu, southern Shantung), with 23°,000. These seven

cities were the major Han commercial and industrial hubs and were located in

the key economic regions in the west, central, northeast, east, and southwest.

They were the distribution centers of special regional products such as iron,

gold, copper, textiles, lacquerware, and agricultural goods. In essence, they

were the nerve centers of the Han economic and business world. The cities were

naturally the centers of political command and economic and military

mobilization to support longtime war efforts. Considering the fact that at the

beginning of the Han dynasty these major urban centers had only 20 to 30

percent of the surviving Ch'in population, their tremendous growth and size

certainly informed the stupendous increase of the Han population in the sixty

some years before Wu-ti's reign. At the same

time, it was also recorded that all earlier Han reigns had made special and

aggressive efforts to promote population growth. Emperor Kao, for example,

decreed in 200 B.C. that all taxes be forgiven for a family with a newborn baby.

Under Emperor Hui, the court even ordered that a woman's whole family be levied

taxes five times higher than normal if she was not married by the age of

twenty-nine (thirty sui). Under these aggressive population policies and

favorable economic conditions, it is reasonable to assume that the population

would have increased over time. In fact, the Han population is estimated, in

different primary sources and later references, to have reached the range of 40

to 50 million before 150 B.C. and increased to the range of 50 million by Wu-ti's early reign, almost five times the early Han

total.

By examining the

availability of the Han economic sources and resources and the strength of the

Han military, modern scholars have estimated that in Wu-ti's time,

the Han government revenue was about 12 billion in cash. However, as soon as

the colonists had pacified they were allowed to return to their former homes. A

few years I was another attempt to settle a permanent agricultural popula1

region and others between 101 and 104 A.D. But when the Q exploded on a large

scale in IIO A.D., the government pulled back to Chang' an. Loc;al officials sent out from the interior, I

knowledge of the region, ordered the abandonment of three (series, the

confiscation of crops, and the leveling of homes so d would return. By 111 the

population of the entire former cap] in Guanzhong was in flight. An

attempt was made between 12 to restore the abandoned commanderies and establish

a military) but when Qiang uprisings resumed in 137, no

significant ref had taken place.

Throughout the

Eastern Han, particularly in the second century, the population

of Guanzhong and the old capital region was dined under the

continuous pressure of Qiang onslaughts. Even in the early decades of

the first century, the northwest regions had been seriously

depopulated. The policies of resettling barbarians inside China and

sending convicts to the frontier may have been in part an attempt to repopulate

these regions. However, these measures did little to check the demographic

decline of the frontier. Census evidence shows that, with one exception, all

commanderies in the west and northwest suffered significant losses, many of

them more than 80 or 90 percent. While the figures are unreliable, a change of

this magnitude, especially when contrasted with the relative stability and even

some increases in inner provinces, probably indicates an actual decline in the

Han population in the border regions.

Contemporary

observations support these statistics. Wang Fu (ca. 90-165 A.D.) noted:

"Now in the border commanderies for every thousand li there are two

districts, and these have only a few hundred households. The Grand

Administrator travels about for ten thousand li, and it is empty. Fine soil is

abandoned and not cultivated. In the central provinces and inner commanderies

cultivated land fills the borders to

bursting and one cannot be alone. The population is in the millions and the

land is completely used. People are numerous and land scarce, and there is not

even room to set down one's foot." Writing several decades later, Cui Shi

described a situation that was virtually identical.

The Eastern Han

government made futile attempts to prevent people from leaving the frontier

regions and to encourage those who had left to return. The Book of the Later

Han (Hou Han shu) states, "Under the old

system [under the Han] frontier people were not allowed to move inward."

In 62 A.D. Emperor Ming offered a payment of twenty thousand cash to any

refugee from the frontier who returned to his old home. As clear evidence for

this ban on inward movement, Zhang Huan, who came from Dunhuang in the far northwest,

was allowed to move to an inner commandery in r67 A.D. only as a special reward

for meritorious service.

But these attempts to

stabilize the frontier population failed. Between 92 and 94 A.D., Emperor He

proclaimed geographic quotas to correlate the number of people recommended as

"filially pious and incorrupt" (the primary route to office) with the

population of a region. For every twenty thousand registered people, a

commandery would be allowed to recommend one man per year. For a population

between ten thousand and twenty thousand, a commandery was granted one

recommendation every three years. But in our A.D. frontier

commanderies with a population of between ten thousand and twenty thousand were

allowed to recommend one man every year. Those with a population of between

five thousand and ten thousand could recommend one every other

year. And those with fewer than five thousand were granted one every

three years. This change shows that the populations of frontier districts were

low and declining. Even the reduced limits were too high for many commanderies.

Wang Fu observed that because of low population, the commanderies in his region

had been unable to recommend even a single man for more than a decade. An

examination of the geographic origins of the "filially pious and

incorrupt" recorded in the Book of the Later Han and on stone inscriptions

bears out his complaint.

The conduct of the

Eastern Han government in the Qiang wars demonstrates a fundamental

weakness of the regime: its single-minded focus on the Guandong region.

The scale of the Qiang disasters and the collapse of Han civilization

in the west and northwest were direct consequences of the eastern government's

ultimate decision to leave the frontier commanderies defenseless and to remove

population from the region. This lack of interest in the security of the west

and northwest, which can be observed throughout the Eastern Han, stems from the

shift of power to the new capital in the east.

When the Western Han

capital was based in Guanzhong, the government pursued a policy of

forcibly resettling population into new towns for the maintenance of imperial

tombs. Through resettlement, powerful provincial families lost their local

basis of influence and fell under the sway of the imperial court. Grain and

other foodstuffs were eventually imported from the more productive Guandong region to maintain the demographic and

economic well-being of Guanzhong.

The Western court

regarded the area "east of the passes" with a mixture of suspicion

and contempt. Jia Yi (201-169 B.C.) observed to the emperor: "The reason

for which you have established the Wu, Hangu,

and Jin passes is largely to guard against the enfeoffed nobles east

of the mountains." In the Discourses on Salt and Iron (Yan tie lun) Sang Hongyang (executed

80 B.C.) remarked: "People have a saying, 'A provincial pedant is not as

good as a capital official.' These literati all come from east of the mountains

and seldom participate in the great discussions of state affairs."

Although men from Guandong played a larger

role in Western Han government after Emperor Wu's death, only when the capital

moved to Luoyang did the situation truly change.

The Eastern Han

founder Guangwu and most of his followers

came from just south of Luoyang, and the rest of his closest adherents came

from the great families of Guandong. Moving the

capital from Guanzhong to Guandong transferred

political power to their region.~ This break with the past was made

self-consciously and deliberately, without regard to strategic considerations,

particularly the fact that the newly reunited Xiongnu were

drawing near Luoyang. Throughout the Eastern Han the court entertained many

proposals to abandon territory in the north or west, leaving the old capital

region vulnerable. In 35 A.D. officials urged that everything to the west of

the Gansu corridor be abandoned, but this was blocked by Ma Yuan, a man from

the northwest. In 11O A.D., in the wake of the Qiang uprisings, a

proposal called for the abandonment of all of Liang province (from the western

end of the Gansu corridor at Dunhuang east to the borders of the capital region

around Chang'ang and even some of the old

imperial tombs. Opponents of this idea argued that the warrior traditions of

the western people were essential to the security of the empire, and that

moving them toward the interior would incite rebellion. By the end of the

Western Han the office of provincial governor ha grown

from a mere inspector into the chief local administrator.

As the governors'

power increased under the Eastern Han, they were able to appoint and dismiss

officials within their provinces without the approval of the court. Holders of

the office thus became autonomous regional lords who, though subject to

dismissal, held sway within their own jurisdiction. Their powers included

military duties, and in the second century A.D., when barbarian incursions and

banditry led to constant combat, the governor replaced the grand administrator

as the person in command of the state's emergency levies . As civil order

decayed and provincial forces spent more time in the field, they took on the

characteristics of semiprivate standing armies.

This development was

a major change in Han local administration and an important step in the fall of

the Eastern Han. The Han dynasty had based its administration on the commandery

and the district-a two-tier structure that fragmented local power into small

units to avoid threats to the central government. The provincial governor,

however, became a third tier, with command of large populations, great wealth,

and significant armed forces-resources that could challenge the authority of

the imperial government. In the second half of the second century A.D.,

governors became semi-independent warlords. When Liu Yan took office as

governor of Yi province, he massacred important local families, gave his own

sons major positions, recruited personal followers from among refugees, and

defied imperial commands. In similar fashion, Liu Yu established his own little

kingdom as governor of You province. He pacified local barbarians, sheltered

refugees, encouraged crafts, and gathered armies. Liu Biao pursued an identical

course of action in Jing province.

By the late Eastern

Han, governors had obtained the power to recruit troops on their own

initiative. This in effect recognized their right to command private armies. In

178 A.D. when the provinces of Jiaozhi and Nanhai (in southern Guangdong and Vietnam) rebelled,

Zhu Jun was sent out as governor and empowered to recruit "household

troops" (one of the earliest uses of the term) to form an army. The

commentary identifies these troops as his servants and slaves. In 189 A.D.

He Jin sent Bao Xin to his home near Mount Tai to recruit troops for

the purge of the eunuchs. By the time Bao Xin returned, He Jin had

been slain. Bao Xin went back to Mount Tai, recruited twenty thousand men, and

joined forces with Cao Cao, the warlord who

ultimately conquered the Yellow River Valley and whose son formally brought the

Han dynasty to an end. The delegation to individuals of the power to recruit

private armies in their home regions shows that the central government had lost

its ability to rule the population. Only through the personal networks of

eminent families in their home regions could the state mobilize a military

force.

Recruits in the

provinces developed strong ties to those who recruited them. In 88 A.D. a

certain Deng Xun had recruited Xiongnu soldiers

to act as guards against the Qiang. Contrary to normal practice, he

allowed these tribesmen and their families to live in his fortress, and he even

let them into his garden. They swore personal loyalty to Deng Xun and

allowed him to raise several hundred of their children as his followers. This

was an exceptional case at the time, but by the end of the dynasty, such ties between

recruits and their commanders were common.

In r89 A.D., when

Dong Zhuo declined to leave his army at the northwestern frontier and

take up an appointment at court, he wrote: "The righteous followers

from Huangzhong and the Han and barbarian

troops under my command all came to me and said, 'Our rations and wages have

not yet been completely paid, and now our provisions will be cut off, and our

wives and children will die of hunger and cold.' Pulling back my carriage, they

would not let me go." When the court attempted to have him yield his

command to Huangfu Song, he replied: "Though I have no skill in

planning and no great strength, I have without cause received your divine favor

and for ten years have commanded the army. My soldiers both great and small

have grown familiar with me over a long time, and cherishing my sustaining

bounty they will lay down their lives for me. I ask to lead them to Beizhou, that I may render service at the

frontier."

This second passage points out another feature of the

Eastern Han's collapse: the proliferation of long-term commands in the field.

In the Western Han, generals had been appointed to command an expedition, after

which the army was disbanded and the general returned to his regular post. The

"Monograph on Officials" of the Book of the Later Han states,

"Generals are not permanently established."20 However, the Eastern

Han created permanent armies stationed at fixed camps. Although in the first

century A.D. the size of armies was kept small and commanders were regularly

rotated, prolonged crises on the frontier required generals to remain with

their armies in the field for years. These armies-which now were composed of

barbarians, convicts, and long-term recruits-became the loyal creatures of

their commanders. Such men had no place in Han society and no home or family to

which they could return. Instead, they formed families at the frontier, and

their lives centered on the person who was, as Dong Zhuo observed, the

source of their livelihood. The Han court never acknowledged this

shift. In Dong Zhuo's biography, his title changed frequently in the

ten years before r89 A.D., but his testimony shows that he and his army stayed

together for the entire period.

Another path leading

to private armies was the development of a dependent tenantry. The absorption

of the old category of "clients" into this new servile group meant

that labor and military service were largely transferred from the state to great

families. In the early Eastern Han, Ma Yuan commanded the services of several

hundred families attached to him as clients. Military service was probably

included in these obligations. Drawing from these service-providing dependents,

the great families were able to assemble armies of hundreds or thousands of

men. Such armies of tenants had overthrown Wang Mang at the end of

the Western Han, and the military capacity of dependent populations existed, as

a latent possibility, right up to the Eastern Han dynasty's collapse. Like the

government's commandery troops, they could be raised in times of emergency.

With the decay of internal order and the outbreak of civil war, these

dependents began to form full-time private armies recruited from what was

becoming a hereditary soldiery. At the same time the dwellings of the great

families became fortified compounds with walls and watchtowers.

The Eastern Han

government gave up all attempts to restrict the rise of a dependent tenantry,

and in so doing abandoned direct administration of the countryside.

Furthermore, as power shifted to the inner court of affines and

eunuchs, the imperial house became separated from the great families who

controlled the outer court. This steady implosion" of imperial power

ruptured the ties that bound the court to the countryside. As social order

steadily deteriorated in the second century A.D., the court discovered that it

had lost the ability to mobilize armies and enforce its own rule.

To counter the threat

of rebellious "inner barbarians" and ultimately the millenarian rebel

movements, the imperial government required military resources that only those

who had developed personal ties to the soldiery could muster: provincial governors,

generals on the frontier, resettled tribal chieftains, great landlords, and, in

a few cases, leaders of religious rebels. While each type of commander had

secured support in a different way, all of them had one thing in common: in an

age of general social breakdown, they could call upon their own armed followers

for security. These various warlords were key political actors in the long

centuries of disunion that would follow the demise of the Han.

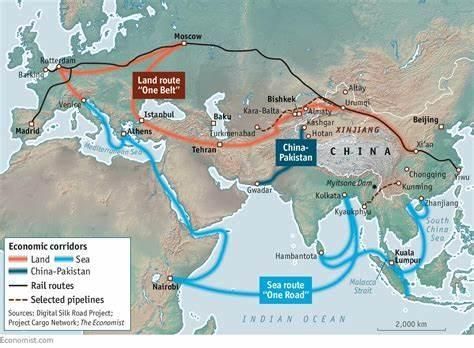

As the Chinese are

quick to point out, the Han leadership has almost exclusively focused on

defense on the international front (even while it suppresses ethnic minorities

in the buffer zones). When China did reach out, aside from during the time of

Mongol domination, it was largely along the Silk Road through Central Asia and

into the Middle East, where China sought to acquire luxury goods more than

vital resources. Even the famed treasure fleets of Zeng He in the early 15th century were more an

expression of China's confidence in its defensive position and its desire for

frivolities than a strategic imperative -- and as threats of invasion from the

north increased, China quickly abandoned its oceangoing enterprises,

considering them expensive and distracting from real priorities.

The Application of Law in the Early Chinese Empires

Written codes first

emerged in the Warring States period, when tax and service obligations were

extended to lower levels of urban society and to peasants in the hinterland.

Local officials responsible for enforcing these obligations required written

laws and regulations stipulating procedures for keeping accounts, the penalties

for crimes, and other aspects of administration. But far from being merely the

tools of rational administration or brutal realpolitik, these codes were

embedded within the religious and ritual practices of the societies from which

they emerged.

Religious Links

Stories in the

Transmissions of Master Zuo (Zuo zhuan),

set in the seventh through fifth centuries B.C., depict Zhou aristocrats

ritually invoking powerful spirits with blood sacrifices and calling upon these

spirits to enforce the terms of their oaths. Such covenants, sanctified through

smearing the lips of participants with the blood of sacrificial animals and

burial of the covenants in the ground to transmit them to the spirit world,

were used to form alliances between states or lineages. They also dictated the

agreed-upon rules to be observed by all who joined these leagues. The recent

discovery of some of these buried covenant (meng) texts from Houma, Wenxian, and Qinyang, along with the rereading of

received texts in light of these discoveries, shows how such texts provided a

religious foundation for a new political authority based on writing.1

In addition to

covenants, a second form of writing that sacralized the earliest legal codes

was inscription on bronze vessels of the type used in the religious cults of

the Shang and Zhou. These inscriptions had served, among other purposes, to

communicate with ancestors and to render permanent any gifts of regalia or

grants of political authority made by the ruler. In the late Western Zhou and

Spring and Autumn periods, several inscriptions record decisions in legal

cases, most commonly disputes over land. A vessel discovered in the cache

at Dongjia village records the punishment

of a cowherd, who was sentenced to whipping and tattooing. By the sixth century

B.C., according to the Transmissions of Master Zuo, the states of Zheng

and Jin used bronze vessels to consecrate their new legal codes.

Thus, inscriptions on sacred vessels that had fixed power and privilege under

the Zhou were adapted to codify the powers of the emerging territorial states.2

The sacralization of

law in covenants and bronzes did not end with the development of more elaborate

codes written on bamboo or wooden strips. Han texts narrate several occasions

in the Qin-Han interregnum and the early Han when ceremonies accompanied by

blood sacrifice were used to consecrate new laws. But by this time the emphasis

had shifted to the text of the oath as the binding force-a recognition of the

power of sanctified writing.3

The religious links of early legal codes are also

indicated by the discovery of substantial samples of late Warring States law in

tombs of officials at Yunmeng (Qin state)

and Baoshan (Chu state). This shows that

legal texts figured in funerary ritual. It is unclear whether the documents

were buried because they were powerful, sacred texts that would protect the

deceased in the afterlife or whether they were an element in the program of

equipping the tomb with all the materials needed to continue the deceased’s

mode of living in the world beyond. In either case, in the still overlapping

realms of funerary cult and political authority, these legal texts played a

role reminiscent of the Zhou bronzes. The deceased held them through the gift

of the ruler, and they were signs and tools of the holder’s power over his

subordinates. Both binding and empowering the texts were carried

into the afterlife to preserve the status of the deceased.

The legal texts

at Yunmeng and Baoshan were

successors not just of the Zhou bronzes but also of the covenants. Like these

ritual oaths, the legal texts were buried in the earth for transfer to the

spirit realm. But more important, the texts played a pivotal role in the

creation of the state by transmitting the policies of the ruler directly to

leading political actors, who in turn transmitted them to their own

subordinates and kin. The names on the buried covenant texts were heads of

locally powerful families who had come into the presence of the ruler of the

emerging state and sworn loyalty to his person and lineage. These oaths bound

not only the family heads but the lesser members of their lineages. Similarly,

the laws of the Warring States were inscribed on ritual texts bestowed upon

political actors, who were bound to the ruler through the receipt of these

sacred objects and who in turn imposed the rules on their subjects. The

physical bestowal of the written statutes and associated documents at or in the

wake of the ceremony of appointment was central to the law’s function, and this

ritualization of the code was carried forward in funerary rites.

This focus of laws on

the ruler’s control of officials is clear in the legal texts from Yunmeng, where the common people appear only in a secondary

role. In these documents, the first and longest section in the groupings used

by modern editors (“Eighteen Statutes”) deals almost entirely with rules for

official conduct, guidelines for keeping accounts, and procedures for the

inspection of officials. The second section (“Rules for Checking”) dictates the

maintenance of official stores and the records thereof. The contents of the

third section (“Miscellaneous Statutes”) closely resembles those of the first

two. The fourth section (“Answers to Questions Concerning Qin Statutes”)

defines terms and stipulates procedures so that officials could interpret and

execute items of the code in the manner intended by the court. The fifth

section (“ Models for Sealing and Investigating”) instructs officials in the

proper conduct of investigations and interrogations so as to secure accurate

results and transmit them to the court.4

The emphasis on the

control of local officials reappears in the text “On the Way of Being an

Official” found in the same tomb. The official is charged to obey his

superiors, limit his own wants, and build roads so that directives from the

center can arrive rapidly and without modification. It praises loyalty, absence

of bias, deference, and openness to the actual facts of cases as the highest of

virtues. It attacks personal desires, acting on one’s own initiative, resisting

superiors, and concentrating on private business as the worst of faults. In

short, it proclaims the new ideal of the official as a conduit who transmits

the facts of his locality to the court and the decisions of the court to the

countryside without interposing his own will or ideas.5 This is the sort of

official that was to be created through the dictates of the legal documents in

the same tomb.

Principles underlying

the early legal codes are also linked to the ritual practices of the period.

Two of particular significance are the idea of punishment as do ut des (the exchange of one thing for another) and the

importance attributed to titles and names.6

Divination Materials Found with the Legal Texts in the

Fourth-Century

B.C. Baoshan tomb reveal a system of curing/exorcism

through sacrifice that follows the Shang pattern. The physician/diviner

ascertains the identity of the spirit causing the disease, its relation to the

patient, and the type and number of sacrifices necessary to assuage it. The

ritual is a mechanical form of exchange with no moral dimension. A similar

process of identification of the spirit culprit and mechanical ritual expulsion

or appeasement informs the "Demonography" found in the Yunmeng tomb. This text's title jie is a technical term in legal documents meaning

"interrogation" but also refers to the commanding of spirits through

the use of written spells; in Zhou documents this term meant "to obligate

oneself to the spirits by means of a written document." Here a term used

for written communications with the spirits was applied to the legal practice

of making written records of testimony by witnesses. This close connection

between religious and legal language figures throughout the texts from

Yunmeng.7

Texts on demon

control share with legal documents not only a common vocabulary but also a

common mode of practice. In both spheres religious and legal-order and control

are maintained through the process of identifying malefactors and applying

graded responses sufficient to counteract the threat or compensate for damage.

Legal punishments incorporated the minute, mathematical gradations that had

characterized sacrificial responses to threatening spirits since the Shang.

This parallel between exorcism and punishment was noted in a passage from the

text of political philosophy Master Han Fei (Han Feizi), written under the

Qin or early Han: "Ghosts' curses causing people to fall ill means that

ghosts harm people. People's exorcising the ghosts means that people harm

ghosts. People's breaking the law means that people harm their superiors.

Superiors' punishing the people means that the superiors harm the people.8

The Yunmeng documents include a "Book of Days" (ri shu)-a text for

determining which days were favorable or unfavorable for certain

activities-which contains a guide to thief catching (a legal concern) through

divination. The guide describes how the physical appearance of the thief can be

determined based on the day when the crime occurred. Other strips deal with

appropriate days to take up a post and indicate the consequences of holding

audiences at various times of the day. Since these mantic texts were buried

together with the legal materials, it is likely that the deceased official or

his subordinates employed them in their everyday administrative activities,

further blurring the line between legal and religious practice.9

The link between law

and religion in early imperial China also entailed bringing the actions of

government into conformity with Heaven and nature. For example, executions

could legally take place only in autumn and winter, the seasons of decay and

death. If a man condemned to death survived the winter, due to a procedural

delay or dilatory action, then he was no longer liable to execution. One story

tells of Wang Wen shu, a harsh official in the