By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Egypt And Its Recent History

By using Islam as a

basis of nationalist legitimacy, both Anwar Sadat and Hosni

Mubarak abandoned the earlier commitments to secular modernity

that marked the Nasser era. It also created an opportunity for

conservative activists to promote their vision of Islam in public life.

In June 2009, U.S.

President Barack Obama delivered an address to the Muslim world proposing a new

start in Arab-U.S. relations. He chose to deliver his potentially trailblazing

speech at Cairo University in Egypt as a recognition of the country’s historic

role in the Muslim world. (Subsequent developments, including the Arab

uprisings and the rise of the Islamic State, dashed hopes for a shift on both

sides.)

Others have argued

that Egypt should be a core member of the regional alliance, which he said

would streamline regional dialogue and cooperation regarding the Palestinian

issue.

However, Egypt’s prominence as a regional leader has been

declining for years. Beginning in the early 1970s during Anwar Sadat’s

presidency, the country became increasingly inward-focused. It prioritized

combating political opposition and Islamist militancy at home rather than projecting

power abroad. Since Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi’s 2013

coup, which overthrew Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated President Mohamed Morsi,

Egypt’s foreign policy has been a reflection of its internal affairs. Countries

that support the Muslim Brotherhood, such as Turkey and Qatar, are considered

ideological adversaries, while those that oppose political Islam, such as Saudi

Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, are seen as tactical allies.

From Pan-Arabism To Egypt First

Britain’s occupation

of Egypt in 1882 cut off Egypt from its traditional foreign policy theaters,

especially in West Asia. Under British occupation, Egyptian nationalism

developed differently from the nationalist movements in West Asia and North

Africa. Most Egyptian heads of state did not try to project power beyond

Egypt’s borders, though there were two notable exceptions: King Farouk and

President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

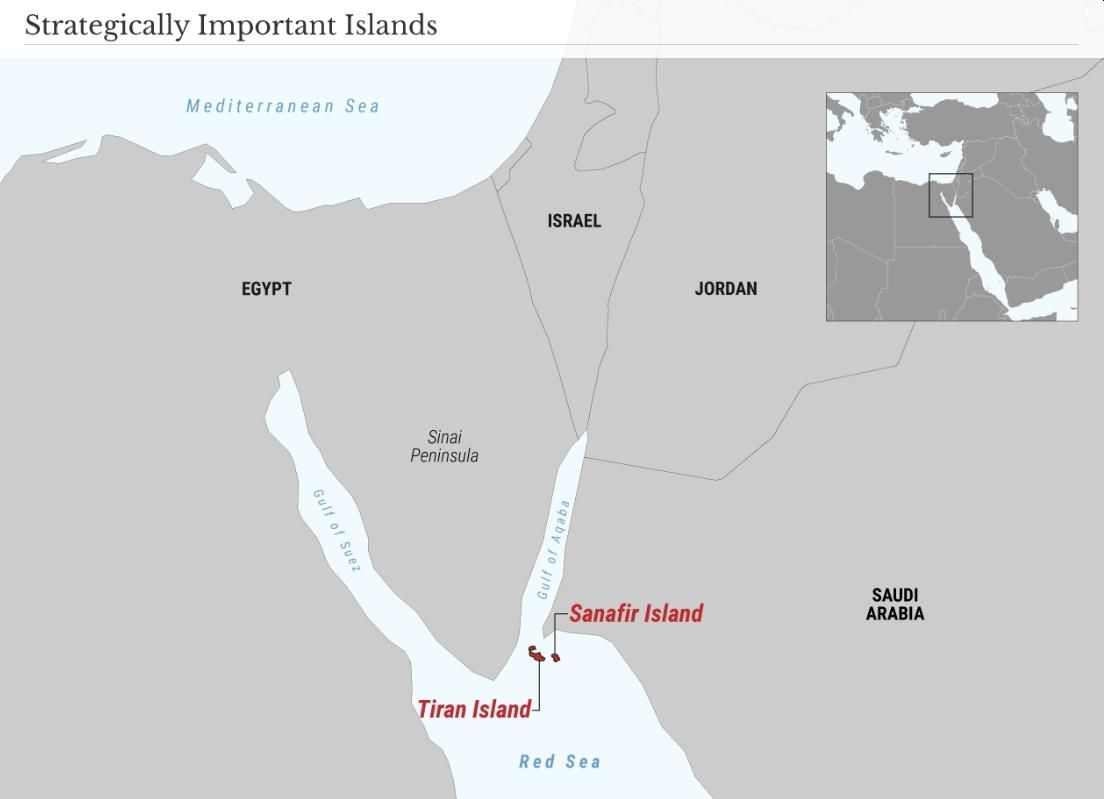

Farouk was a

descendant of Muhammad Ali, who seized power in Egypt in 1805 and aspired to

create an Arab kingdom. Farouk decided to lead Egypt into the 1948 Arab-Israeli

war against the wishes of his own government and army command. In 1950, he

closed the Tiran Passes to Israeli shipping, and the following year, he played

an instrumental role in drafting the Joint Arab Defense Treaty to confront

Israel.

Nasser, meanwhile,

had distinct Arab roots, unlike most Egyptians, and hailed from the Asyut

governorate in Upper Egypt. He militarily and economically supported the

Algerian war of independence in 1954-62. In 1957, he sent troops to Syria to

defend the country against a possible Turkish invasion. In 1960, he dispatched

army units to Kuwait after Iraqi President Abdul Karim Qasim threatened to

occupy it. Two years later, he sent one-third of the Egyptian army to Yemen to

defend the fledgling republican regime after a coup overthrew its king. Even

after Egypt’s staggering defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War, Nasser remained a

powerful figure in the Arab world. Though many Arab leaders viewed him as an

enemy, the vast majority of the Arab public saw him as the uncontested champion

of Arab nationalism.

Since Nasser’s death

in 1970, however, Egypt’s regional ambitions have been limited. Egyptian

presidents have recognized that the poor state of the country’s economy

disqualified it from playing a leading role in regional politics. Anwar Sadat,

who succeeded Nasser, opposed sending a single Egyptian soldier to fight on

behalf of Arabs. During his presidency, he was boycotted by most Arab leaders

because he made unilateral peace with Israel. Hosni Mubarak, who became

president in 1981 after Sadat’s assassination, sent Egyptian troops to Saudi

Arabia in 1990 as part of the U.S. coalition to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi

occupation. But his move was not motivated by a desire for Egypt to become a

regional power but by a desire to stop Iraq from becoming one.

El-Sissi’s Politics Of Regime Survival

Current President

Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi has mostly followed suit. Since

becoming president, he has been preoccupied with internal security matters. As

the only Egyptian president to stage a coup to seize power since 1952, his top

concern has been staying in control, not reestablishing Egypt’s leadership of

the Arab world. His focus has been on safeguarding Egypt’s borders from

incoming militants and arms, which could be used to support Egypt’s homegrown

militant movements.

El-Sissi has no

regional power ambitions. However, he doesn’t want the aggressive foreign

policies of the Saudi and Emirati crown princes to overshadow Egypt’s

historical role in the region. He has deep concerns about the Gulf countries’

peace deals with Israel, which threaten to limit the need for Egypt’s regional

mediation. Cairo gained its reputation as a regional peace broker after the

1991 Madrid Peace Conference. But since then, the Palestinians have turned to

Turkey to facilitate a reconciliation between Hamas and Fatah, while Hamas has

sought Qatar’s help to ease Israel’s blockade on Gaza. Egypt is also

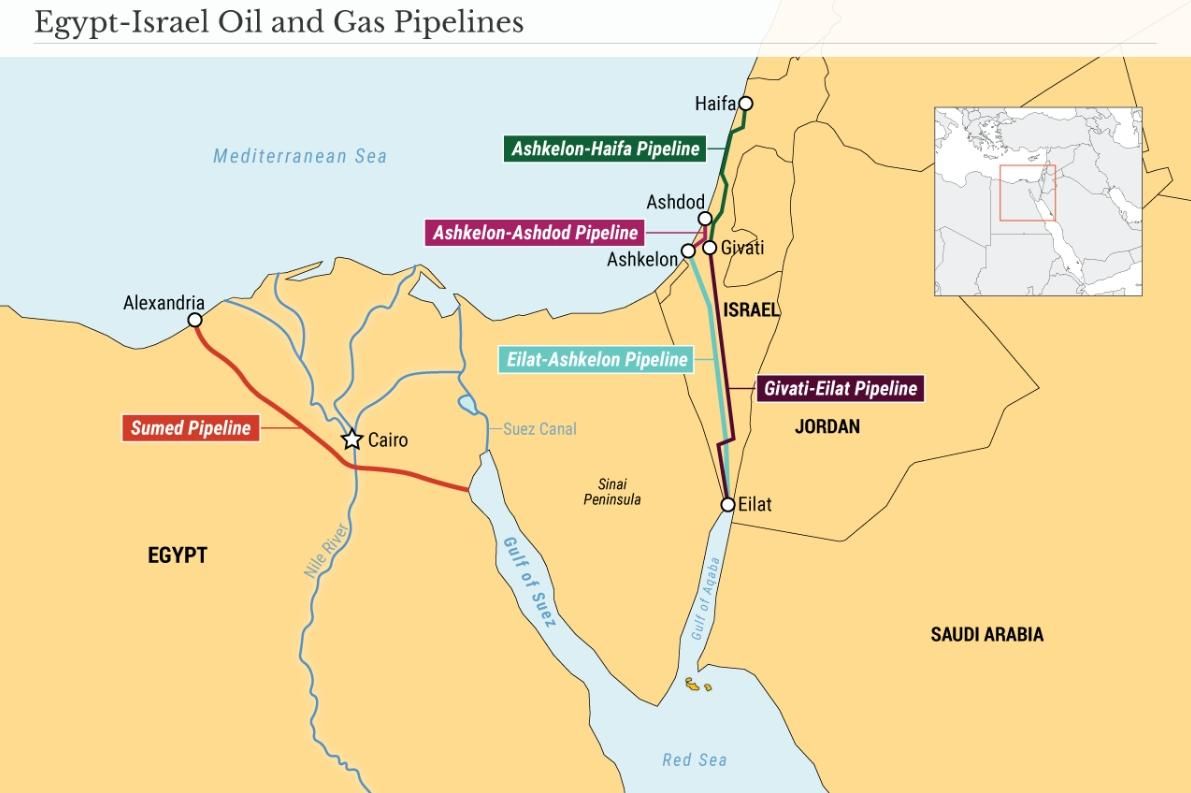

increasingly economically alienated. Last October, Israel Pipeline Company

signed a deal with the UAE to transport oil from Abu Dhabi to Europe via the

Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline. The agreement effectively reduces oil shipments via

the Suez Canal by 17 percent and compromises Egypt’s Sumed oil pipeline from

the Gulf of Suez to Alexandria.

Egypt adopted a

relatively proactive and pro-Palestinian approach to Israel’s recent operation

in Gaza. (By comparison, it was relatively passive during similar bouts of

violence in 2009 and 2014.) In 2014, Egypt pressured Hamas to accept Israel’s

terms for a cease-fire, but this time around, it brokered a deal that took

effect without any preconditions. It painted Israel as the aggressor in the

conflict, and a prominent Egyptian Islamic scholar called on Muslims to seize

Jerusalem and halt Israel’s West Bank settlements.

Still, Israeli Prime

Minister Benjamin Netanyahu thanked el-Sissi for

facilitating the cease-fire. As for Hamas, it was skeptical of Egypt’s offer of

$500 million for Gaza’s reconstruction, knowing that Egyptian companies run by

the armed forces would lead the reconstruction efforts and that these efforts

would increase Egypt’s influence over Gaza.

Egypt’s

government-controlled media referred to Cairo’s efforts to negotiate a

cease-fire deal as the dawning of a golden era in Egyptian foreign policy. The

media lauded Egyptian officials’ negotiation skills, ignoring the fact that

Biden played the decisive role in stopping the fighting. The claim that Egypt

was restoring its relevance as an international peace broker rings hollow

because in Egypt, Gaza is often considered more of a domestic matter rather

than a regional one. (Cairo occupied the Gaza Strip from 1948 until 1967.) In

any event, successful mediation does not make a country a regional power.

Egyptian media have

exaggerated el-Sissi’s achievements. They claimed

that his forceful diplomacy protected the Palestinians against Israeli

aggression. It also spread propaganda about his military coup, claiming it was

a popular revolution that saved Egypt from the Muslim Brotherhood. The media

also glorified Egypt’s massive troop mobilization in the northwest – which it

claimed resolved the Libyan crisis to Egypt’s advantage.

Egypt has myriad

other problems with which to contend. It has a weak economy, heavy debt, poor

educational system and high unemployment. According to the World Bank, Egypt’s

per capita income in 2019 was $3,000 compared to $8,000 for the Middle East and

North Africa region. Although real incomes saw modest growth over the past few

years, they are not sustainable in the long term because Egypt’s economic

reforms are superficial. The Egyptian economy relies heavily on the public

sector, led by the armed forces. The International Monetary Fund strongly

recommended that the government promote the private sector, but instead, it

increased the military’s involvement in the economy.

The 1952 military

coup ended a century of capitalistic development. Nasser’s nationalization of

the economy had devastating consequences for Egypt’s economic growth. When

Sadat made peace with Israel, he slashed the military budget but allowed the

armed forces to play an active role in the economy to generate revenue. Under

Mubarak, the military effectively dominated the economy, a trend that only grew

under el-Sissi, who’s dependent on the loyalty of

senior army officers who oppose any attempts at privatization.

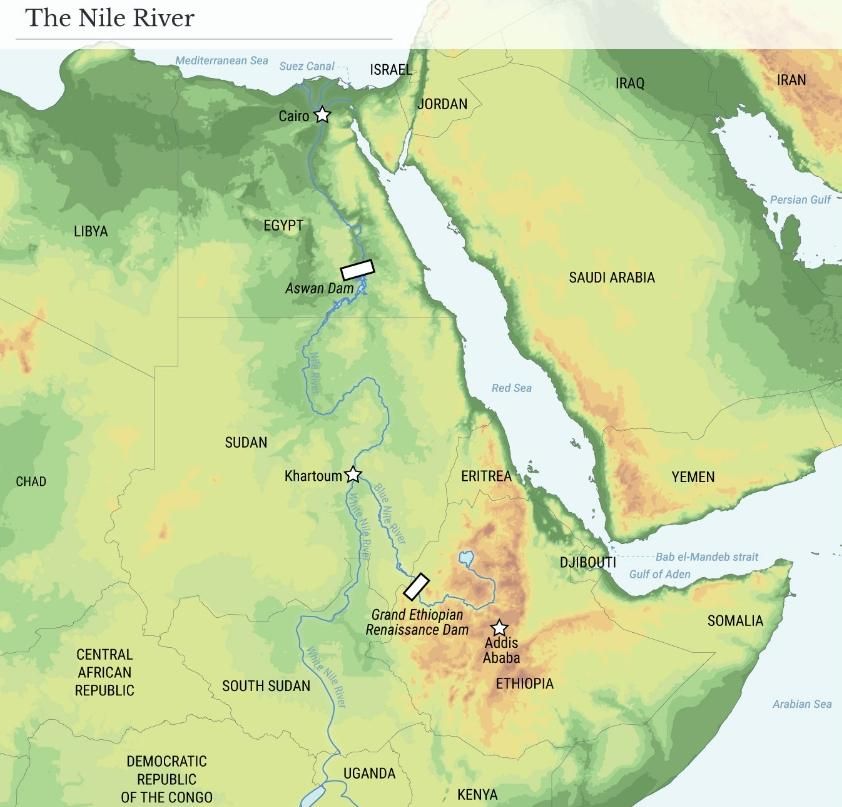

Egypt is also facing

a low-intensity insurgency in northern Sinai and an intensifying water dispute

with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. (The project, which is

still under construction, has already decreased Egypt’s production of staple

crops – wheat, rice, and sugar – by more than 25 percent.) El-Sissi believes

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is seeking to transform his country into an

economic hub and marginalize Egypt’s role in the region.

A country with an

economy controlled by its military and facing an existential threat to its

water supply can hardly expect to become a regional power. El-Sissi has shifted

Egypt’s focus from the Middle East to Africa, in part because of the dispute

over the dam, but he remains too preoccupied with the existential threat from

the south to worry about restoring Egypt’s regional power status.

Egypt enjoys

geostrategic advantages that qualify it to play a leading regional role. It

straddles Africa, Asia and Europe and controls one of the world’s most

important maritime routes. It is the Arab world’s most populous country and has

its most homogeneous population. However, Egypt remains inwardly focused, and

its people have little interest in non-Egyptian affairs. Considering the state

of the country’s economy, it’s unlikely these conditions will change any time

soon.

Yet Egypt had

a weak response to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), a massive

project that threatens to decrease the flow of water downstream through the

Nile River. Yet the expenditure of billions of dollars on arms despite the

government’s refusal to resort to military action to settle its dam dispute.

But this level

of criticism directed at the president is extremely rare in Egypt.

Many Egyptians share

opinions on the water issue. And that el-Sissi should

not have signed the 2015 Nile Agreement, which absolved Ethiopia from

respecting Egypt’s water claims.

Egyptian leaders are

unaccustomed to being criticized. For example, the Egyptian media never

criticized former President Gamal Abdel Nasser during his lifetime. After the

1967 Six-Day War, he accepted full responsibility for its disastrous outcome

and admitted the failures of the armed forces. Still, the Egyptian public

showered him with praise and believed he would lead them to victory. But Nasser

knew how to communicate with the people, unlike el-Sissi,

who in 2016 announced that he would deploy troops throughout the country in six

hours after activists called for mass protests against the deal to give Riyadh

control over the Red Sea islands.

Legacy Of Apathy

There are many

explanations for the Egyptian people’s hesitation to rebel against repressive

leaders. One argument attributes political inaction to the country’s rule by

foreigners – Persians, Romans and Arabian Muslim conquerors – for more than two

millennia. Even prior to that time, Egypt was ruled for three millennia by the

pharaohs, to whom Egyptians attached divine attributes that justified their

absolute power.

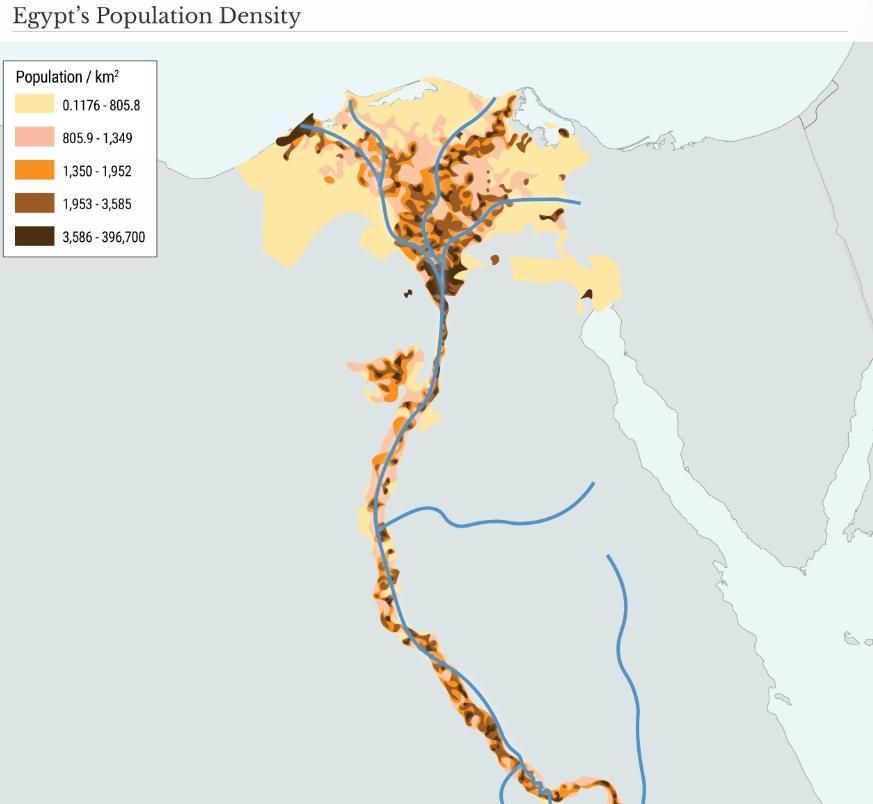

Another explanation

is that hydraulic societies promote political apathy because imperial dynasties

monopolize water supplies and regulate their distribution. Egypt’s population

lives on just 5 percent of its 1 million square kilometers of land, making it

easy for its rulers to control them in the flat and narrow plains.

The pharaohs’

establishment of the world’s first centralized state, when Menes united the

delta and upper Egypt 5,000 years ago, enabled them to keep the population at

bay under the hegemony of a powerful political entity. The historical

experiences of a people brought together by destiny feed into their collective

consciousness, which can either trigger or inhibit collective action. While

individual Egyptians do take issue with the regime, these personal acts of

defiance do not grow into widespread demands for reform. Those who do call for

change become pessimistic over time, realizing they cannot mobilize their

fellow citizens who fear government reprisal. Eventually, they reach the point

of believing that they do not stand a chance against the state’s overwhelming

machinery of coercion.

Stability And Tolerance

Despite the tendency

toward apathy, Egypt has witnessed several bouts of unrest throughout its

history. In 1919, a pro-independence uprising swept through Egypt after the

British arrested nationalist leader Saad Zaghloul, who was later exiled. In

1922, the British declared Egypt an independent state and introduced a system

of participatory politics – though they remained in control of the Suez Canal

area. In 1968, workers at the Helwan industrial complex south of Cairo

protested against the light prison sentences given to air force commanders

deemed responsible for Egypt’s defeat in the Six-Day War. In 1971-72, student

demonstrations erupted against President Anwar Sadat’s reluctance to go to war

against Israel and liberate Sinai. (He reneged on a promise to end Israeli

occupation before the end of 1971.)

But these public

displays of discontent were short-lived. Egypt’s agricultural society and

predictable pattern of living engendered the development of a rich culture that

puts a premium on stability and tolerance. Egyptians welcomed Alexander the

Great as their liberator from the Persians and treated him as a deity. They

accepted the Ptolemaic Kingdom that succeeded him, especially after its kings

immersed themselves in the Egyptian way of life. Egyptians even accepted

Cleopatra, who was of Macedonian heritage, as one of them. After succumbing to

the Roman Empire and its Byzantine successor, they did not resist the Muslim

conquest in the 7th century and appreciated the Arab military commander Amr ibn

al-As for freeing them from Byzantine rule. They adopted the Arabic language,

unlike, for example, the Persians and Turks, who adopted Islam but clung to

their own language and cultural heritage.

When the Fatimids

conquered Egypt in 969, Egyptians converted to Shiism. Then, in 1169, when

Saladin gained control over Egypt, they reverted back to Sunnism. They did not

resist the French, who occupied Egypt between 1798 and 1801 – in part because

the French brought with them modernization and, unlike the Mamluks, treated the

Egyptians with respect. The Ottomans sent Muhammad Ali, an Albanian army

officer, to Egypt to rein in the Mamluks after the French departure, but he

established a dynasty that lasted from 1805 until 1952. He founded modern

Egypt, making it a cultural, educational and literary hub.

Disappointment With Self-Rule

In 1952, Egyptian

army officers staged a military coup, which eventually led to Nasser taking the

reins of power. He wanted to develop Egypt economically but got bogged down in

military adventures throughout the region. He led Egypt from one disaster to another:

the 1956 Suez War, the Yemen War and the disastrous Six-Day War. Yet, Egyptians

did not hold him accountable for his erratic policies, and many still view him

as a national hero. After Nasser’s untimely death in 1970, Anwar Sadat became

president. He deconstructed Nasser’s socialist economy, introduced

neoliberalism and created a class of nouveau riche business entrepreneurs. In

1977, hundreds of thousands of poor Egyptians protested against the

government’s curtailing of food subsidies – though they made no political

demands. Sadat found it more practical to reinstate the subsidies and ignore

the recommendations of international financial donors. Hosni Mubarak, who

succeeded Sadat after his assassination in 1981, allied with the neoliberal

class and allowed the army to become a significant economic player, to the

detriment of most Egyptians, who languished in poverty. In 2008, the rise of

the April 6 reform movement – a coalition of young activists and organized

labor – was a testament to the Mubarak regime’s decay and the armed forces’

resentment of his scheme to have his son Gamal succeed him.

The torture and

brutal killing in June 2010 of an innocent young pharmacist triggered

short-lived and inconsequential protests in Cairo and Alexandria. In contrast,

the uprising in Tunisia in 2010 that followed the death of a street vendor

named Mohamed Bouazizi – who set himself on fire after being harassed by police

– triggered the Arab Spring protests and reminded Egyptians of the excesses of

their country’s security forces. The ouster of Tunisian President Zine El

Abidine Ben Ali after 24 years in office gave Egyptians hope that they could do

the same.

After Mubarak

resigned following mass protests, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces

allowed Mohammed Morsi to become president with the intention of deposing him

and reclaiming complete political control. Politically inept, Morsi angered

many Egyptians, and the military overthrew him in 2013. El-Sissi became

president in 2014 and continues to maintain a tight grip on power.

Under his leadership,

authoritarian rule in Egypt has reached a new peak. Egypt’s history and

geographic isolation have led many Egyptians to accept the country’s despotic

leadership, believing that better days are ahead. But Egyptian society can

flourish under the management of a bold leader – which it hasn’t had in

decades.

For updates click hompage here