By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Elections And Climate Extremes

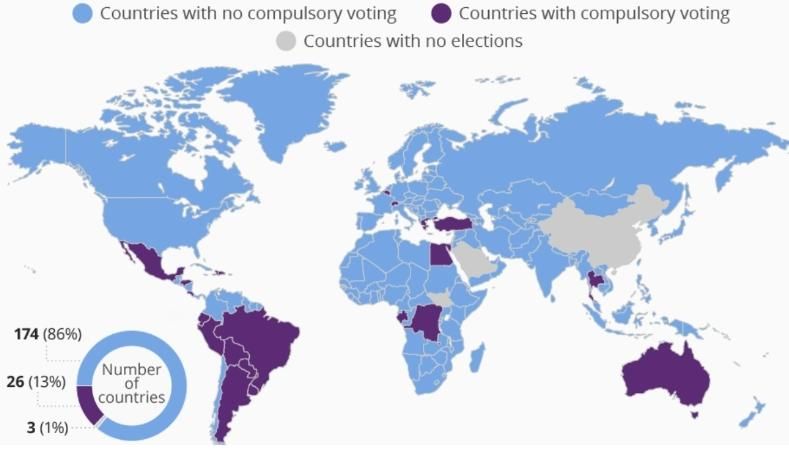

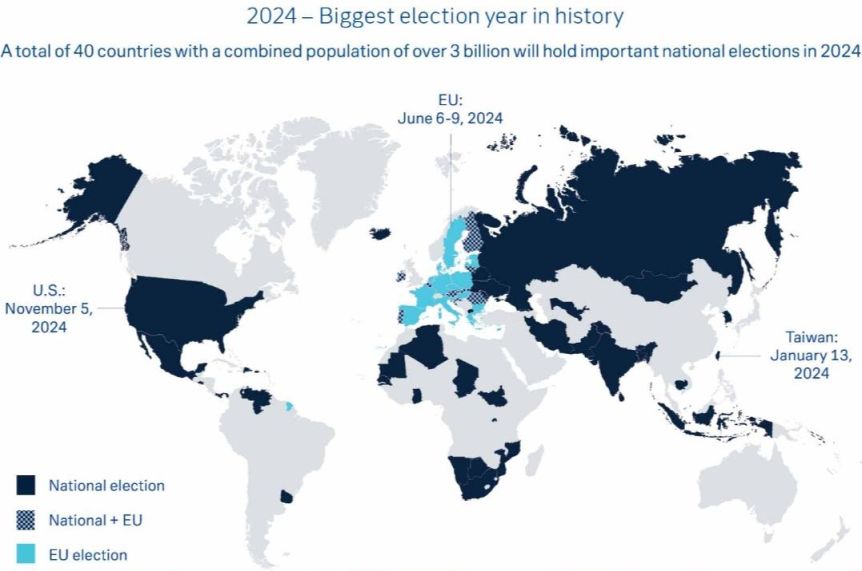

This year, at least

sixty-eight countries will hold elections, with billions of voters heading to the

polls. Voting will be subject to many of the usual electoral risks, including

disinformation campaigns, foreign interference, and rigging by incumbents. In

some states, both incumbents and challengers could even use violence to keep

certain people at home.

But there will be

another factor, one not yet widely considered, that could skew results: the

physical forces unleashed by climate change. They present a unique and novel

challenge. Although all electoral threats are serious, the ones brought by

climate change have the potential to disenfranchise voters even in the absence

of malevolent intent. The disenfranchisement of even a few voters can make a

profound difference in election outcomes, as in the case of the 537 votes in

Florida that determined the U.S. presidential election in 2000. As extreme

weather events become more frequent, the risk to voters will grow.

Electoral authorities

in all countries, including Australia, Canada, India, and the United States,

must take action to ensure that—even if polling places, ID cards, and

communication networks are damaged or destroyed—citizens can exercise their

fundamental democratic right to vote. Options include relocating polling

stations, making the rules on registration more flexible, and protecting

communications networks.

Flooding The Polls

Since the Industrial

Revolution in the mid-1800s, societies have produced ever higher amounts of

carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases, chiefly by burning fossil fuels.

These gases linger in the atmosphere for decades, if not centuries, and there are

now more of them in the atmosphere than at any time in the past 4.3 million

years. Temperatures are soaring as a result. Every one of the ten hottest years

in recorded history occurred during the past decade, with 2023 leading the

pack. In the 2015 Paris Agreement, 196 countries and international

bodies—including China, the European Union, and the United States—pledged to

limit the increase in global average temperature to below two degrees Celsius

above preindustrial levels, and preferably to 1.5 degrees. But the necessary

commitments to achieve these goals have yet to be made, much less implemented.

Moreover, although these numbers may sound modest, detailed analyses by the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the group of scientists charged with

informing UN climate negotiations, show that every tenth of a degree of warming

above 1.5 has a severe impact. Higher temperatures bring more intensity to

hurricanes and cyclones, for example, as well as inland and coastal flooding,

wildfires, and extreme heat waves.

In 2023, global

temperatures climbed to 1.36 degrees above preindustrial levels. Recent

assessments by the UN Environment Program conclude that by 2100 the planet will

reach three degrees above preindustrial levels unless current policies are

strengthened. Already, extreme-weather disasters are occurring with greater

frequency. In the United States, billion-dollar catastrophes—including

wildfires, severe storms, and flooding—struck on average every two

to three months during the last two decades of the twentieth century. Now they

occur on average every two to three weeks. Similar trends likely exist around

the world. As a result, emergency responders, government officials, and

nongovernmental aid groups have less time to respond, recover, and redeploy.

And when weather disasters repeatedly strike a particular community, residents

struggling with the aftermath of one calamity find themselves less able to deal

with the next—physically, financially, and psychologically.

Such disasters will

surely upend elections. Indeed, they already have. Between January 2019 and

January 2024, more than a dozen countries contended with extreme weather events

around the time of local or national elections, according to the International

Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. In March 2019, for example,

Mozambique was hit by Cyclone Idai just before the opening of the voter

registration period. The storm displaced more than 400,000 people, many of whom

lost the identity documents that they needed to register to vote. The storm

also destroyed thousands of classrooms used as registration, polling, and

vote-counting centers. Six weeks later, Cyclone Kenneth struck, destroying

electoral registers, polling materials, and printers. Meanwhile, outbreaks of

cholera, which can spike after flooding, further impeded voting.

A similar situation

occurred in Pakistan in 2022 when extreme precipitation led to flooding that

covered a third of the country before its national contest. Close to eight

million people were displaced, with hundreds of thousands moving into temporary

shelters. Some of the displaced could not access government-issued national

identity cards, which meant that they could neither register nor vote.

Meanwhile, floodwaters severely damaged many polling places. It made others

completely inaccessible. Analysis by World Weather Attribution, an

international scientific consortium, concluded that climate change likely made

the extreme precipitation 50 percent more intense.

Richer countries have

more resources to respond to climate-worsened disasters. But they are by no

means immune to disruption. In the United States, Hurricane Ian hit Florida

just six weeks before the 2022 midterm elections, damaging polling locations

and other infrastructure used by more than 12 percent of the registered

electorate. Rainfall from Hurricane Ian was 18 percent higher than it would

have been absent climate change, according to researchers at SUNY and Lawrence

Berkeley National Laboratory. Then, beginning in March 2023, Canada suffered

the worst year of fires in its history, leaving it struggling to conduct

regional elections. Climate change doubled the risk of the spring wildfires by

creating hot, dry, and windy conditions, which persisted for the rest of the

year. In the fall, wildfires spread to the sparsely populated Northwest

Territories and displaced 65 percent of inhabitants in the weeks leading up to

the general election. And in Spain, extreme heat during July 2023 prompted some

voters to don swimwear to cast their ballots. The World Weather Attribution

consortium concluded that the month’s maximum heat would have been “virtually

impossible” absent human-caused climate change.

Expect The Unexpected

If current trends

continue, extreme weather events will increasingly compromise citizens’ right

to vote. Election officials must therefore understand how climate change can

impact elections. They must think, of course, about election day itself, when

voters must often stand outdoors for hours in line to cast their votes. In an

era of extreme heat, such queues will be dangerous for those at risk of heat

stress, including those over 65 or with medical conditions, as well as pregnant

women and children brought by their parents. But election day is just the tip

of the iceberg. As previous disasters have made evident, extreme-weather events

can disrupt activities along the months-long electoral process, from voter

registration through to vote counting. Severe weather can also impact

candidates’ campaigns, as well as canvassing by their supporters.

Climate disruptions

hardly end when extreme weather does. Voters driven from their homes by

emergency conditions may flee without the identity documents they need to

register or cast a ballot. Even if they do get their papers out, floodwaters or

flames may damage or destroy them. Voters may also face lengthy periods of

displacement far from their assigned polling places if their homes remain

uninhabitable. Even for those voters who are not displaced, road closures and

other lingering transportation disruptions can make it impossible to reach the

polls. Similarly, climate-worsened disasters can displace election officials

and poll workers, rendering them unable to reach their offices or polling

stations, which may themselves have been damaged or destroyed. When storms

interrupt power supplies, election officials face additional challenges both in

keeping polling places operational and in communicating with colleagues and the

public. And ballots themselves can be destroyed by the same elements that take

out identity documents, either before distribution or after their collection.

Regardless of whether

one’s vote determines the outcome of an election, individuals who are unable to

vote because of climate-driven extreme weather lose a fundamental democratic

right. Preparing for the inevitable worsening of climate impacts on elections

is, therefore, essential. Yet almost no one has taken action. The U.S. Election

Assistance Commission, for example, advised in 2014 that “planning minimizes

the disruption and aids in a quick recovery while preserving the security and

integrity of the election.” But a decade later, U.S. election officials have

largely ignored climate risks in their planning, even as they make other

changes to the electoral system. Americans can increasingly vote by mail, for

example, but battered roads may prevent postal services from delivering ballots

or conveying completed ballots to election officials.

Other countries are

also failing. In 2023, the Election Commission of India revised its Manual on

Electoral Risk Management to include a section on natural disasters. The

updated manual, however, makes no mention of climate change or extreme heat.

This is even though most voters under 80 are required to vote in person and

India has experienced high temperatures during this year’s elections, which

began in April and stretched into early June. During much of that period,

human-caused climate change made extreme heat in portions of the country at

least fivefold more likely, according to the Climate Shift Index. To protect

human health, the head of the Indian meteorological service, Mrutyunjay

Mohapatra, urged authorities to provide adequate supplies of water, as well as

fans and air-conditioned spaces. Notwithstanding these measures, voter turnout

was significantly lower than normal, prompting Indian authorities to create a

task force to examine the impact of heat waves on the election. News reports

indicate that at least 77 people died from the extreme heat during the final

ten days of voting, including 33 poll workers.

Elsewhere election

officials have embraced new, more flexible approaches, on a mostly ad hoc

basis. Following a devastating storm in Quebec in 2022, Canada extended polling

station hours. Amid the 2023 wildfires, the province of Alberta offered to mail

special ballots to 29,000 evacuated residents and the Northwest Territories

broadened its “Vote Anywhere” initiative, allowing voters to use any polling

location within the jurisdiction. The Territories also postponed its elections

by six weeks. After flooding in 2022, Australia allowed flood victims to vote

by phone, an option that previously had been allowed only for disabled voters

due to the significant staff time required. Meanwhile, in the United States,

California has developed mobile voting units that it can deploy during

disasters. But these initiatives, although all useful, are not yet broad

enough, nor systemic enough, to make sure elections are resilient to disasters.

Voting In A Warming World

To better account for

climate change, election officials can start by improving their own capacity to

prepare for and respond to disasters through training and planning. Officials

can, for example, use widely available tools to assess climate risks when organizing

elections, including Climate Central’s Coastal Risk Screening Tool, which

provides free, highly localized flood risk maps for coastal

communities—allowing officials to identify safer locations for polling

stations. Artificial intelligence may be able to play a role in site selection

by digesting data on vulnerabilities, population locations, power sources,

potential transportation disruptions, and other variables.

Officials must also

afford themselves greater flexibility in running elections. Experts at the International

Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance and the International

Foundation for Electoral Systems recommend measures such as allowing same-day

voter registration, thereby permitting citizens to register and cast ballots in

a single process, and creating online systems to enable voters to update their

addresses more easily after displacement. Another option is allowing voters

multi-day periods in which to cast their votes. Officials could also let voters

obtain replacement or temporary ID cards at no cost. Similarly, installing

backup election and power equipment, creating alternative methods to produce or

reprint ballots, and expanding avenues of public outreach can lessen voting

disruptions.

Major disasters

typically disrupt communications, meaning that climate-resilient election plans

should include robust methods to inform citizens of when and where to vote and

to inform polling officials of changes to their duties. Where electrical power is

available, radio and television announcements can spread information about

alternative polling places, expanded times, and other adjustments, as can

social media if connectivity allows. Nongovernmental organizations can help

election officials in getting the word out. In the United States, the Lawyers’

Committee on Human Rights runs nonpartisan hotlines to answer questions from

voters regarding election processes. Such hotlines can help disseminate updated

information.

The right to vote is

fundamental to democracy. Climate extremes will batter and test it, as they

already have. But building more resilient election infrastructure and

introducing greater flexibility in how, when, and where people register and

vote can limit the damage. Doing so will be increasingly essential on a rapidly

warming planet. Every voter should have the ability to cast a vote that gets

counted—no matter the weather.

For updates click hompage here