By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

America’s Awkward Energy Insecurity

Problem

For the United States—a

country that, especially under incoming President-elect Donald Trump, aspires

to be not only energy secure but energy dominant—one energy insecurity problem

remains, which could dog the development of a key source of new power.

Some five months

after the United States swore off imports of Russian-enriched uranium, a key

source of fuel for the nuclear reactors that provide almost 20 percent of the

country’s electricity, U.S. reliance on imports, including from Russia, remains an issue. At stake is less the fuel supply

for the current fleet of nuclear reactors than the fuel for the coming

generation of advanced nuclear plants that are meant to provide all the extra

power needed to run data centers and power artificial intelligence; Russia has

a complete monopoly on the commercial production of that richer blend of fuel.

(Tech companies are so eager to line up new sources of power that Microsoft

is re-commissioning part of the shuttered Three Mile Island nuclear

power plant in Pennsylvania and will buy all of its output.)

U.S. imports of

Russian enriched uranium for reactor fuel fell announcing its own ban on exports to

the United States last fall, Russia promptly issued waivers of its own to allow fuel to be sent to U.S.

customers.)

Europe, after a

buying spree in 2023 to stock up on specialized Russian fuel needed for

Soviet-era reactors, also cut back its purchases of Russian uranium last year,

but it is still a buyer—especially France. The International Energy Agency

(IEA) recently released a report that noted 2025 will be a record year for

nuclear power generation and the start of an era of huge nuclear growth, but it

also underscored the risks of relying on countries like Russia and China for

such a critical industry.

“Highly concentrated

markets for nuclear technologies, as well as for uranium production and

enrichment, represent a risk factor for the future and underscore the need for

greater diversity in supply chains,” the IEA said.

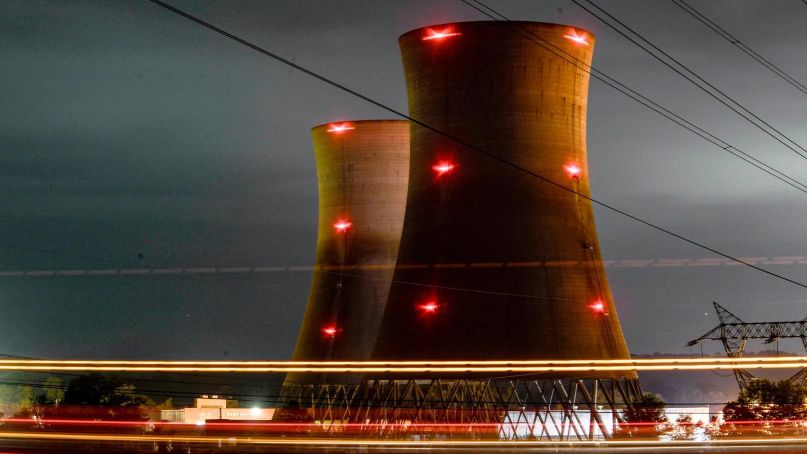

The shuttered Three

Mile Island nuclear power plant stands in the middle of the Susquehanna River

in Pennsylvania on Oct. 10, 2024.

But sourcing nuclear

fuel is not like sourcing fossil fuels: It can take years to secure government

and regulatory permits that allow for the import of enriched uranium to keep

reactors running. That means that even the three-year grace period included in

last year’s legislation to find new suppliers to replace Russia leaves little

cushion.

“If I were a nuclear

power operator, I would be making sure I have fuel in place for two to three

years from now, because that is how long it can take to go through the

process,” said Cindy Vestergaard, a senior fellow at the Stimson Center, a

nonpartisan think tank.

The legislative ban

and the decrease in Russian imports are the beginning of U.S. efforts to come

to grips with a self-inflicted energy vulnerability that came about with the

end of the Cold War and the sudden availability of cheap, abundant nuclear fuel

from a former geopolitical rival. This transition period means the United

States will remain largely dependent on foreign sources of fuel for its

reactors, a stark contrast to its virtual self-sufficiency in oil, gas, and

coal.

“We have not fixed

the problem entirely,” said Rowen Price, a nuclear policy advisor at Third Way,

a center-left think tank. “The fact of the matter is that we still rely on our

geopolitical adversaries for uranium.”

At the same time that

Russian imports in the United States have gone down, imports of Chinese

enriched uranium have increased, sparking the Biden administration to review if

China is helping Russia indirectly circumvent U.S. efforts to kick its reliance

on bad actors.

“We certainly don’t

want to be in a position where we are trading reliance on [Russian President

Vladimir] Putin for [Chinese President] Xi Jinping, so it adds to the urgency”

of rebuilding U.S. and European enrichment capacity, Price said.

And that, precisely, is

the second part of the U.S. push, after the phased ban on Russian uranium

imports. Last December, the U.S. Energy Department picked six companies to compete for up to $2.7 billion

in contracts to supply both the low-enriched uranium (LEU) needed for

today’s fleet and the so-called high assay, low-enriched uranium (HALEU) needed

for the next generation of advanced nuclear reactors.

“We don’t have the

capacity [for enrichment] in the United States, there is a huge delta between

the demand and the supply,” said Christo Liebenberg, CEO of LIS Technologies,

one of the six companies picked. LIS, unlike most enrichment firms that use traditional

centrifuges to spin gaseous uranium hexafluoride into enriched uranium, is

trying to perfect the use of lasers to do the same job more efficiently and at a

much lower cost.

“It’s a matter of all

hands on deck. The demand is already huge today, but now there is the surge” to

meet the proposed tripling of the size of the U.S. nuclear fleet, he said.

Another company picked by the Energy Department for the new

project is part of Urenco, the European consortium

that already operates the sole U.S. enrichment facility for nuclear power

plants. Experts said it should be relatively easy to keep fueling the existing

nuclear fleet from stockpiles and imports from friendly nations while additional

enrichment capacity is built.

But the big question

remains of what solutions will emerge for HALEU, which is needed for the next

generation of reactors, as well as more traditional reactors meant to be the

tech industry’s solution to ravenous power demands for data centers and artificial intelligence.

Companies such as

Terra Power and X-energy both need HALEU for their advanced reactors, which are

expected to be operational by 2030 provided the fuel is available.

Initially, the plan was to get the highly enriched fuel from Russia,

but its war in Ukraine and the later U.S. ban has thrown the fuel question into

uncertainty.

Conventional

enrichment technologies can make HALEU if they add extra steps and build new

facilities with additional security. Another issue, noted Vestergaard, is that

commercializing HALEU will require an entirely new way to transport the nuclear

fuel because the casks used for lower-enriched uranium can’t be used for

HALEU.

So far, there’s been

a chicken-and-egg problem with HALEU: Unless and until there is a healthy

and long-term demand, there has been little incentive to invest heavily to

produce it. The Energy Department program aims to kickstart that production,

but it is not clear if traditional centrifuge technologies or laser enrichment

technologies can provide the advanced fuel as soon as the reactors require.

“The urgency on HALEU

is that we are rapidly approaching the timeline for these new

projects, and they need fuel, and we don’t have anywhere to get that fuel

yet,” Price said.

For updates click hompage here