By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers 2

February 2020

According such articles like among those in Foreign

Affairs and The

New European they have decided who is the most dangerous man in the world.

And Andrew S. Weiss vice president for studies at the Carnegie

Endowment, where he oversees research in Washington and Moscow on Russia and

Eurasia referring to Aleksandr Dugin wrote an investigative article

titled; With Friends Like These: The

Kremlin’s Far-Right and Populist Connections in Italy and Austria.

Already in January

2020, the Italian weekly L’Espresso revealed that one of the three Russian

individuals who met, in 2018, with the functionaries of the Italian Lega to

discuss financial support for the far-right party was an actual intel officer

Andrey Kharchenko. Kharchenko is also closely connected to Russian fascist

Alexander Dugin, which means that Russian intelligence services are overseeing

Dugin's activities.

Putin's brain or simply the poster boy of populism and

the radical right?

Whereby Foreign

Affairs called him "Putin's

brain" at the launch of the neo-Eurasian movement we are about to

explain, it is true that the then-Russian deputy foreign minister, Victor

Kalyuzhny, and the deputy speaker of the Russian senate, Alexander Torshin, were listed as members of its higher council we

have to see these matters in a differentiated manner.

Aleksandr Dugin with

a Kalashnikov in front of a tank of the South Ossetian insurgent army, June

2008:

Der Spiegel reported

how Alexander Dugin had set thirty army tents housed his 200 attendees

undergoing paramilitary training.

To place this in a

larger context, Russian geopolitical thinking with deep roots in history has

always influenced its foreign policy - under the Soviet regime, it was

disguised. Only after August 1991 was geopolitics officially accepted as a

political doctrine. Neo-Eurasianism became the most important and influential version of it.

This anti-Western theory had its roots in Eurasianism,

a theory introduced by Russian émigrés. It was based on two conceptions: the Russian view of a declining West and its

conspiracy theory. The first-mentioned view has its precursors even in the West

in Oswald Spengler's writings as well as in the national socialists' worldview.

However, the above

view of the decrepit West has always been combined with the so-called

conspiracy theory. The West is a hotbed of evil forces conspiring against

Russia. In plain language, all misfortunes and shortcomings in Russia's history

can be explained as caused by the West dominated by Jews and Masons...

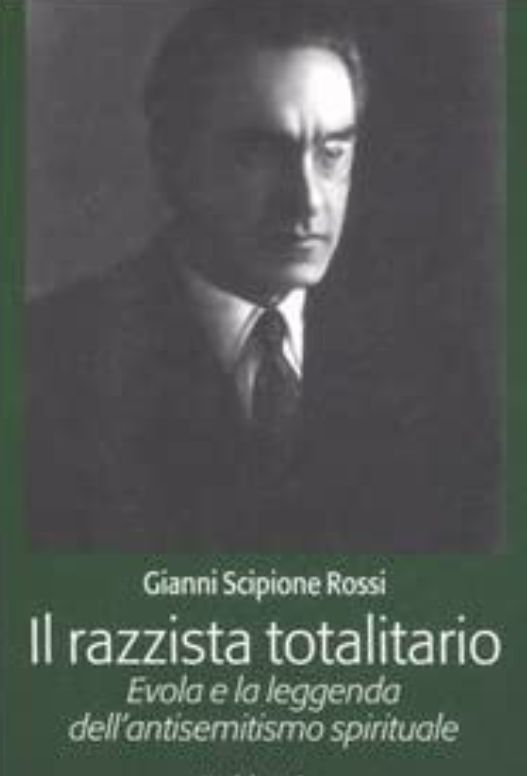

While more than the

older Slavophiles, Dugin's intellectual forebears are often Western New Right

thinkers such as the Belgian neo-Fascist Jean

Francois Thiriart and, most

importantly, Julius Evola.

It is known that

during his time in Vienna, and upon his return to Italy, Julius Evola's plan

was that of creating a political movement bound more firmly (than had

henceforth been the case; i.e., with Fascism and Nazism) to the principles of

aristocracy and honor, which are the foundation of traditional power. This idea

was shared by some Fascist intellectuals, whereby Evola himself pointed out in

the postwar period, it was a matter of forming elites of young people who knew

how to resist modernity and the false temptations of populism, but above all of

being able to complete the Fascist and Nazi revolutions on a supranational

level by conferring them with cultural meaning.

The issue of

esotericism was also relevant in the context of Evola's collaboration with the

German Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service) and Abwehr (Military Intelligence

Service) because his relationship with the German military secret services took

place given the preparation of a model of man and society that was not intended

for everyone but rather only for the "initiates” who were capable of

demonstrating an inner equilibrium and knowledge superior to others.1

For Dugin, “Fascism

has nothing in common with extreme nationalism, a nationalist radicalism at the

border of chauvinism and racial hate. Despite the existence of a racist and

chauvinistic aspect in German National-Socialism, this element was not defining

the core of the ideology.” According to him. The Ahnenerbe,

the main institution in charge of elaborating Nazi esoteric myths and rituals,

was the model of this nonracist Nazism. It welcomed cooperation with

non-European peoples from Asia and the Middle East. They were considered part

of a shared Aryan genealogy, Only the Atlanticist line of Nazism advanced by

Bavarian circles and by Hitler himself promoted theories of racial destruction.

In contrast, the Russophile Eurasianist line, led by Reinhard Heydrich, was

open to non-European peoples.

In one of his first

trips to Europe, in 1993, Dugin also met Leon Degrelle

just before the latter passed away. Degrelle, founder

of the Fascist Walloon party Rexism that supported

total collaboration with the Nazis, became Volksführer

of Wallonia and the leader of the Walloon contingent of the Waffen SS, which

was sent to the Eastern Front.

One of Dugin’s

disciples, Nina Kouprianova, is married to white

nationalist leader Richard Spencer. Kouprianova has translated

Dugin’s works which were published by Spencer’s publishing house,

the Washington Summit Publishers. Spencer himself, before he came to the

public eye, has been hosted on RT regularly as a

commentator. More recently, Aleksandr Dugin has also been platformed

on Infowars [archive], run by far-right conspiracy theorist Alex Jones.

We

covered Richard Spencer in reference to the great replacement

conspiracy theory (when he marched chanting

'Jews will not replace us’), whereby he rejecting being a neo-Nazi and

said that he perceived himself closer to the tradition of Alain de

Benoist, Dugin, and the French New Right.

However throughout,

Spencer increasingly became associated with white nationalist websites and

groups, including Andrew Anglin's Daily Stormer, Brad Griffin's Occidental Dissent, and

Matthew Heimbach's Traditionalist Worker Party. In 2015 it attracted broader public attention, particularly

through coverage on Steve Bannon's Breitbart News, due to the above-noted

support for Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign, he was

interviewed on CNN.

The extreme right in East and West

More than other political

cultures, the culture of the extreme right is a highly segmented ecosystem of

groups or factions, movements, blogs, websites, and publishers and magazines

that simultaneously collaborate and compete. Far-right groups tend to overstate

their numbers, influence, and connections to position themselves as part of a

structured international movement. Moreover, their networks are difficult to

analyze open sources may be lacking. Discussions may be underground. Rumors can

spread from one source to the other without reliable documentation. Personal

friendships can be more important than ideological commitments. Additionally,

identifying a connection between two movements does not necessarily reveal any

direction of influence. Ideological stimuli are more often a matter of

cross-pollination than a unidirectional dynamic.

Contacts between

far-right movements in Europe and Russia existed before the 1917 Bolshevik

Revolution, even though they were rare because the Russian groups were strongly

anti-Western and insisted on Russia’s distinct path (Sondenveg).

However, the same ideologies were circulating in both the European and Eurasian

spaces; this can be seen on the byways of the Protocols

of the Elders of Zion, which provided the doctrinal foundation for many

anti-Semitic movements. And more recently, those whose ultranationalist

rhetoric mirrors Dugin’s own call for genocide the Ukrainian, echoing Nazi

ambitions against Europe’s Jews.

To this belonged the

Kremlin-backed annual Foros Forum convenes in Crimea,

a majority ethnic Russian region in Ukraine, and aims to "shape a new

generation of young Russian politicians," according to one of the

organizers Duma deputy Sergei Markov. A selection of young activists from

Kremlin-created youth groups like Nashi and the Youth Guards join the leaders

and activists of Ukrainian pro-Russian movements to listen to lectures by the

likes of Aleksandr

Dugin, a leading light of the Eurasia movement, which preaches a

Russian-led power block as an alternative to the West. "People gather to

support our fraternal Ukrainian nation, which is groaning under the pressure of

NATO," says Gennady Basov, leader of the nationalist Russian Bloc Party, a

pro-Moscow pressure group based in Crimea.

There was also an

emotional defense of the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine. Its authors were descendants

of some of the

most powerful Russian aristocratic families that fled the country after the

Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

"Knowledge of

the recent past, namely the past of the pre-revolutionary Russia, gives us the

opportunity, and with it the duty, to expose the obvious historical

falsifications that led to the current drama in Ukraine.” Titled “Solidarity

with Russia,” the letter went on to criticize Western “aggressive hostility”

toward Moscow: “Russia is accused of crimes, without a priori evidence it is

declared guilty.” The authors said that they could no longer accept the “daily

slander against modern Russia … its leadership and its president,” who, they

write, subjected to sanctions and dragged in the dirt against elementary common

sense.

The letter was penned

by Prince Dmitry Shakhovskoi, a well-respected Slavic

scholar who lives in France. His wife, Tamara, was signed by more than 100

princes, counts, and others whose names ranked among the most storied tsarist

Russia, Tolstoy, Pushkin, Sheremetev. These families

maintain a tight-knit community across Europe sustained by galas and black-tie

reunions.

Contradictory as it

may seem, however, support for the Kremlin among White émigrés and their

descendants is hardly new. It goes back almost to the revolution when the new

Bolshevik secret police first began actively recruiting Russians living in

Europe. Some believe that Shakhovskoi’s letter

represents the Kremlin’s latest attempt to exploit the émigré community. And,

in that, it sheds light on what exactly Russian President Vladimir Putin is

trying to accomplish with his new Cold War with the West.

Collaboration between

the White émigrés and the Kremlin goes back to the 1920s. The Bolshevik secret

police began actively recruiting members of the so-called first wave of émigrés

soon after settling abroad. Other sympathizers changed their minds about the

Communists after World War II when many believed Stalin saved the motherland

from the Nazis. Deceived about his rule, many émigrés returned to the USSR only

to be sent to the gulag.

Over the following

decades, other émigrés and their children and grandchildren settled across

Europe, the United States, and elsewhere assimilated into Western society.

However, many maintained informal ties to the USSR, attending Soviet embassy

receptions and Kremlin-organized cultural events and traveling to the Soviet

Union.

Although White émigré

descendants’ formal relations with Russia’s new authorities warmed after the

Communist collapse in 1991, they remained brittle, as some exiled families

tried in vain to reclaim former property.

A young billionaire

named Konstantin

Malofeev is also believed to provide an important conduit to the White

émigré community. The founder of an investment firm named Marshall Capital

Partners, who calls himself an “Orthodox businessman,” has been the subject of

at least two criminal investigations into theft from state-controlled banks.

However, the probes were dropped around the time he’s believed to have begun

playing a central role in financing and directing the separatist rebellion in

eastern Ukraine, which Moscow has fueled with arms, troops. The whipping up of

propaganda espousing a radical Russian

Orthodox-based nationalism. Novaya Gazeta, one of Russia’s few remaining

independent newspapers, reported that Malofeev was behind a memo to the Kremlin

proposing the

annexation of Crimea and part of eastern Ukraine even before the country’s

old pro-Moscow government had collapsed. He is also close to the head of the

Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Kirill, who helped draft a new law for

censoring the Internet.

Malofeev’s

connections to the émigré descendants include, according to Kirilenko and

others, a close friendship with Shakhovskoi’s son,

who works in Moscow and is married to the daughter of Zurab Chavchavadze, a

Georgian prince who is one of the representatives of a wing of the Romanov

family in Russia. Malofeev also heads foundations that advocate Russian

Orthodox values and funds a private Orthodox school of which Chavchavadze is

the director. Although Malofeev’s star in the Kremlin is believed to have waned

since last year, it’s clear he remains one of a small group of like-minded

insiders who carry out useful

roles for the Kremlin.

Viktor Moskvin, the

director of another state-funded cultural group in Moscow called the Alexander

Solzhenitsyn House

of Russia Abroad, said it was his idea to approach Russian media about

publicizing the letter after Shakhovskoi told him

about it during a White army celebration in Paris. His group, which is chaired

by the widow of the famous dissident writer and strong Putin supporter and was

founded to collect an archive of émigré documents and relics, also provides a

direct conduit for Moscow’s ties to Russian émigrés. Moskvin insisted that Shakhovskoi’s letter is important because its signatories

represent the cream of Russia’s historical elite. “They are representatives of

the oldest and most illustrious Russian families, who played a huge role in the

Motherland’s history,” he told the government’s official paper of record, Rossiiskaya Gazeta. “Today, they include professors of

leading universities, scholars, doctors, successful entrepreneurs, and

journalists. They support Russia and the Russian people with their souls.”

Cooperation with European extreme right-wing parties

Putin isn’t aiming to

galvanize the support of only émigrés. The many hundreds of social media

comments supporting Shakhovskoi’s letter included

French and other Europeans who said they were swayed by the idea that the

writers had special authority to understand the Kremlin’s actions. “I find here

a taste of Free France, where the monarchists rubbed anarchists,” read a

comment on a French translation of the letter.

Moscow is encouraging

such sympathies among both far-left and far-right groups to help split Western

opinion. That’s an old game for Moscow: European Communist parties and other

groups acted the same way during the Cold War. Now the Kremlin is quietly cultivating

radical parties across the continent, including some openly neofascist, united

by the common goal of undermining the European Union.

Despite the paradox,

many far-right parties across Europe, including France’s anti-immigrant

National Front and the Dutch Freedom Party, are voicing loud support for Putin.

Russia also has ties with Hungary’s nationalist Jobbik party, Slovakia’s

People’s Party, and Bulgaria’s anti-EU Attack movement. National Front leader

Marine Le Pen recently praised Putin, saying that “he proposes a patriotic

economic model radically different than what the Americans are imposing on us.”

Her party went to take out a loan worth more than $10 million from a Russian

bank owned by a Kremlin ally. Last year, both the National Front and the United

Kingdom’s anti-EU UK Independence Party won 24 seats in the European

Parliament, an institution they want to sideline.

Kremlin allies and

insiders have been busy hosting conferences to rally support groups in Serbia,

Switzerland, and elsewhere. Yakunin, the billionaire who organized the

Tunisia-Sevastopol cruise for a new generation of White Russians, is co-chair

of an organization called the Franco-Russian Dialogue Association. Putin and

former French President Jacques Chirac set up in 2004 ostensibly to improve

economic and cultural links. Last summer, at the group’s annual assembly, held

at the Russian embassy in Paris, Yakunin railed against Washington for inciting

European countries to enact new sanctions.

In Austria last May,

Konstantin Malofeev organized a meeting of European right-wing politicians.

Alexander Dugin headlined the event. With members of the National Front and

Austria’s Freedom Party in attendance, “it looked like a congress of

anti-European forces,” Kirilenko says. “They paint themselves as supporters of

traditional values that are under attack in the West to mobilize public opinion

that Russia is the genuine home of spirituality.”

Contacts between

far-right movements in Europe and Russia existed before the 1917 Bolshevik

Revolution, even though they were rare because the Russian groups were strongly

anti-Western and insisted on Russia’s distinct path (Sondenveg).

However, the same ideologies were circulating in both the European and Eurasian

spaces, particularly the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which

provided the doctrinal foundation for many anti-Semitic movements.

While the political

relevance of right-wing populist challenges to liberal democracy is widely

recognized, the theoretical bases of right-wing populism are rarely the targets

of sustained analysis. Yet what Alberto Spektorowski

writes about the New Right perhaps applies also to right-wing populisms more

generally: their importance “lies . . . in [their] theoretical innovation.”2

Despite these

attempts to “excuse” fascism from its racist elements, Dugin is certainly not

indifferent to racial theories.

Like Julius Evola,

one of his main sources of inspiration, he believes in spiritual races that

separate peoples into two major categories: subject races and object races. It

goes without saying that the choice of terminology, subject and object,

borrowed from twentieth-century philosophy, is a way of implying superiority

and inferiority without the consequent legal condemnation.

The third line of

argument anchors fascism into a discursive framework, nationalism, that enjoys

more positive connotations in some parts of Russian public opinion. To do this,

Dugin plays with words and blurs terms to make them interchangeable. According

to him, the concept of National Socialism sounds negative, even though the two

words that comprise it are positive. Therefore National Socialism should be

understood as no more than “German socialism” because fascism is a proletarian

regime “whose central figures are the peasant, worker, and soldier.”

The Franco regime,

for instance, would not qualify as fascist because it promoted a “national

capitalism” that is actually the enemy of authentic fascism. Similarly,

“Russian Fascism can be described as Russian socialism.” At the same time,

Marxism-Leninism was lost in a sterile doctrinal rigidity, according to Dugin.

Russian National

Socialism would be “more peasant than the

proletariat, more communitarian and cooperative than statist, more regional

than centralized. From Dugin’s perspective, fascism would thus be no more than

a “leftist nationalism.”

Dugin deploys the

words “nationalism” and “fascism” interchangeably. He starts his article

“Leftist Nationalism” by stating, “The twentieth century knows only three forms

of ideology: liberalism, communism, and nationalism.’ In “Fascism without

Borders and Red,” he included a very similar sentence but replaced nationalism

with fascism. He proclaimed that “Russia [had] passed two ideological moments,

the communist and the liberal. . . . Fascism is the remaining one.”

However, to develop a

more solid narrative that would make fascism adequate to Russian political

traditions. Dugin has gone further. He has invested himself in revamping the

German Conservative Revolution tradition to foster fascism's reintegration into

the “politically correct” realm by rebuilding its intellectual genealogy.

Offshoots and further sources

The Eurasian Movement

has an offshoot, the Global Revolutionary Alliance (GRA). Its manifesto,

dated April 1, 2017, espouses an apocalyptic vision that humanity is at the

verge of an end to “capitalism, resources, society, nations, peoples,

knowledge, progress.” The GRA downplays the significance of wider social

transformations and places the blame for these processes, rather

conveniently, on the “global Western-centric world” and “the ruling class

of globalism.”

The GRA calls for a

global revolution: “liberalism … must be destroyed, crushed, overthrown,

obsolete.” It brands the United States as the “country of absolute evil,”

vowing to partner with any anti-US, anti-Western, anti-NATO, and anti-liberal

countries in their revolution. At its core, the GRA manifesto synthesizes

conspiracy theories about a “deep state,” globalization, mutants, cyborgs, the

sinister meaning of the Statue of Liberty, and so on. What is unsettling is

that the manifesto does not read at all like a conspiracy theory. Instead, it

is framed as reality, aiming to unite people worldwide to safeguard their

“normal” way of life in collectives and railing against the freeing

individualization and “atomization” of the West. At the foundation of the GRA

ideology is so-called neo-Eurasianism. As Dugin

explains, triumphant liberalism moved out of the political realm to

metamorphose into “biopolitics,” absorbing flesh and blood to become a

lifestyle. He asserts the need for an ideology to defeat neoliberalism. If it

is not defeated, the only remaining option is a “dissolution” into triumphant

liberalism, its lifestyle, and its global world. Dugin offers a solution that

he believes is powerful enough to strike down neoliberalism and its lifestyle.

This is where neo-Eurasianism strikes, offering what Dugin sells as a

complete package: a cause, an ideology, and a strategy for a revolution to

reclaim one’s identity and tradition. In essence, Dugin proposes “an alternative model of a conservative future.”

Neo-Eurasianism includes such conflicting notions of

“fundamental conservatism (traditionalism), social-conservatism and

conservative revolution.” Such palingenesis in Dugin’s ideas intertwines with

the as seen above ideas of Julius Evola, an Italian fascist traditionalist, who venerated

traditional society and considered modernity as corruption.

Dugin systematically

refers to the main representatives of this Conservative Revolution: the Jungkonservativen, with Arthur Moeller van der Brack,

Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt, Othmar Spann, and Wilhelm Stapel; the National

Revolutionaries, mostly Ernst Jiinger and Franz

Schauwecker; and the German National Bolsheviks around Heinrich Laufenberg and

Ernst Niekisch. Dugin points out the tensions between

these movements and Hitlerism and emphasizes several contradictory points:

Hitlerism was further to the right than the Conservative Revolution, Hitler was

a Russophobe. In contrast, the others were Russophile, and Hitler was a racist

while the others were non-xenophobic nationalists.

To rehabilitate

fascism, Dugin thus needs to dissociate the Nazi regime from the Conservative

Revolution. However, he largely fails at convincingly articulating this crucial

distinction. For example, lie affirms that “Fascism is the Third Way,”!] that

“the most complete and total (although also quite orthodox) incarnation of the

Third Way was German National Socialism,” and that “National Socialism

undoubtedly took and realized the impulsion coming from the conservative

revolutionary ideology. In this usage, the three terms, Nazism, Fascism, and Conservative Revolution,

largely overlap, and Dugin's demonstration of their differences and

contradictions fails to be conclusive. Last but not least, although Dugin seeks

to promote fascism that diverges from Nazism, his major philosophical

references have all directly inspired the Nazi regime: Julius Evola, Carl

Schmitt, and Martin Heidegger.

In an interview in

2014, Dugin definitively renounced what he calls the second and third political

theories (communism and nationalism/fascism, the first one being liberalism)

and stated that the fourth proposes a full break with the first three because it

no longer seeks to accommodate modernity, but instead denies it in its

entirety. Whereas in the early 1990s, he claimed that Russia had tested

liberalism and communism and had to turn to a third choice,

fascism/nationalism, twenty years later, he proclaimed, “Liberalism, communism,

and fascism, ideologies of the twentieth century, are finished. That is why it

is necessary to create a new, fourth political theory.

But despite pedantic

declarations of novelty, Dugin had merely rearranged the doctrines in which he

has always believed. He states that of all forms of conservatism, the most

interesting is that of the Conservative Revolution, which he defines by repeating

the formula of Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, “Conservatives who have preceded

us have sought to stop the revolution, we must take the lead of it.”

National Bolshevism

and Eurasianism are the two ideologies that are

closest to the fourth political theory. Dugin himself, therefore, offers the

keys necessary to decipher the falsification of his “novelty.” He recognizes

that the drama of the fourth political theory is "that it was hidden

behind the third (Nazism and fascism). Its tragedy is to have been overshadowed

historically by the third, and being allied with it, given the impossibility to

conduct an ideological war on three fronts (against liberalism, communism, and

fascism/Nazism). Nothing thus changed, except the window dressing, and Dugin

today, as twenty-five years ago, continues to give voice to what fascism is a

la Russe.

Ideologically. Eurasianism is the Russian version of the European

far-right. The founding fathers of Eurasianism,

living as emigres in European capitals in the 1920s and 1930s, were impressed

and inspired by the German Conservative Revolution and its combination of

“nationalism" and “conservatism." They associated its main thesis,

the need for a Third Way between capitalism and communism, with a belief in

Russia as the Third Continent between Europe and Asia. While they renounced

Nazism, which they regard as pure racism, they followed very closely Italian

fascism, in which they saw the inspiration for a future Eurasian Russia. Today,

Alexander Dugin, the main ideologue of neo-Eurasianism

since the collapse of the Soviet Union, has played a key role in mediating

far-right theories in Russia. His definition of Eurasianism

entirely overlaps with the Conservative Revolution a la Russe. Yet, contrary to

the founding fathers of Eurasianism, Dugin borrows

from the whole spectrum of far-right doctrines and does not limit himself to

the Third Way theories. So-called Esoteric Nazism directly inspires him, and

his metaphorical language calls indeed for violence. He also borrows from some

of the New Right theories. He thus offers a complex doctrinal spectrum that is

always in intimate dialogue with movements coming from Western Europe.

Eurasianism in Russia and the far-right in Europe share more than

doctrinal principles inspired by fascist traditions. Their beliefs push them to

interpret the international order with similar toolkits. In both cases, the

enemy is identified as the United States (both a country and a civilization)

and liberalism (both political and moral, and sometimes, but not always,

economic) as its ideological backbone. In their worldview, resistance to this

international order can emerge only from countries or regions where

anti-Enlightenment values are well preserved and cherished. Europe should be

one of them. This statement is aspirational: the Europe they dream of does not

exist. On the contrary, both Eurasianism and the

far-right complain about the construction of the European Union, which is

viewed as a bureaucratic, dehumanized machine that serves U.S, interests and

liberal values, the accepted or implied objectives of which are the destruction

of authentic European values and the underlying identity of the continent.

Today neo-Eurasianism holds the view that Europe’s real nature is to

ally with Eurasia to form the Heartland, a continental mass able to resist

maritime powers such as the United States, its subordinate, the United Kingdom,

and their allies on other continents, thanks to an extreme ideology directly

inspired by fascism. Thus neo-Eurasianism is not

anti-European, but instead anti-Western, anti-Transatlantic, and anti-liberal,

and it believes in the common destiny of European and Eurasian peoples.

A majority of the

European far-right shares this vision of a united continent. Their enemies are

the same, especially the European Union, as are their hopes for a pan-European

future for “white” or “Christian” peoples in which Russia would have a role. This

is not only a result of recent evolutions linked to European construction. Many

of the Conservative Revolution theoreticians of the 1920s and 1930s were

impressed by the messianic forces unleashed by the Bolshevik Revolution and

sought a strategic partnership with a phoenix-like Russia. During World War II,

the Nazi regime and its allies searched for a pan-European idea that would

catalyze nationalist energies toward a common goal without triggering

fratricidal conflicts. Fascist groups revived and

updated this idea in the 1960s, as they sought to abandon Nazi ideology on

German exceptionalism in favor of a pan-European phenomenon. Their movement.

Young Europe (YE) was named after the 1942 Third Reich journal of the same

name. One of YE‘s main ideologists. Jean-Franco is Thiriart,

who served in the Waffen-SS and defended collaboration with the Nazi regime,

advanced the slogan of a Europe "from Reykjavik to Vladivostok,” thus

inviting Soviet Russia to join this new political construction. In the 1980s, Thiriart reaffirmed his pledge: “If Moscow wants to make

Europe European, I preach total collaboration with the Soviet enterprise. I

will then be the first to put a red star on my cap, Soviet Europe, yes, without

reservations.”

This shared

aspiration of what Europe’s future should be, unified, detached from the

trans-Atlantic world, and turned toward its continental neighbor, Russia, also

provides a common ground for the current honeymoon between European far-right

parties and Vladimir Putin’s Russia. But the toolkit for analyzing this agenda

is far more complex than the one needed to comprehend the contacts between

Dugin's neo-Eurasianism and his far-right

counterparts in Europe. Contrary to frequent media statements, Dugin’s theories

are not the direct inspiration for Putin's regime and its quest for great

powers. The Kremlin has not made official any new state ideology inspired by

the Conservative Revolution, even if it borrows some themes. However, in

Europe, the Kremlin has recently acquired more or less the same allies that

Dugin has cultivated for more than two decades. As seen from the Kremlin, those

who denounce Brussels’ technocrats and their submission to U.S. interests are

potential friends of Russia. In addition to this geopolitical orientation, the

European far-right shares with the Russian regime a similar anti-liberal

narrative that denounces economic and political modernity, individualism, the

destruction of so-called traditional values, and the imposition of external

cultural standards.

But although Dugin

and the European far-right belong to the same ideological world and can be seen

as twins, the alliance between Putin’s regime and the European far-right is

more a marriage of convenience than one of true love.

This brief sketch

outlines how Eurasianism in Russia and the far-right

in Europe share many beliefs, principles, and common geopolitical aims. This

volume aims at untangling this puzzle by tracing the ideological origins and

individual paths that have materialized in their permanent dialogue. The

historical roots of this exchange have only been partially studied. The mutual

influence between the founding fathers of Eurasianism

and the German Conservative Revolution remains largely unexplored, as do the

poorly understood relations between postwar far-right movements and the Soviet

Union. This volume focuses on the contemporary situation, with regular

references to history, to provide the keys to analyze s in Europe.

Julius Evola

Evola’s work has

recently seen a transnational renaissance. It has influenced the alt-right

movement in the US, the Greek neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party, and the Hungarian

nationalist Jobbik party. Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s former chief adviser, is

also attracted by Evola’s traditionalist and anti-modernist philosophy, his

anti-liberal aristocratic elitism, his spiritual racism, and his male-dominated

worldview. These groups and individuals use Evola’s work to call for a

Christian-dominated Western world that must be defended against all immigrants,

Muslims in particular. Such calls ignore the fact that Evola was highly

critical of Christianity and regarded Islam as the more

spiritually advanced and thus more traditional religion, a classic example

of cherry-picking during Evola’s initial adoption by Italy’s far-right 1970s.

Nevertheless, Evola’s growing popularity among the radical right today calls

for a deeper understanding of his teachings and philosophy to better understand

the present transnational right-wing extremist and terrorist scenes.

Even though his

heterodox ideas were not always well received by the Italian ruling class of

the time. They earned him the suspension of some publications by the PNF and

Germany's suspicion of the Nazi hierarchies.3 Evola contributes to the dissemination

in Italy of important European authors of the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries: Bachofen, Guénon, Jünger, Ortega y Gasset, Spengler, Weininger, translating some of their

works and publishing critical essays. The complexity of his thought gave him,

even after the end of the war, a large following in the Italian and European

conservative circles, from the most radical ones of neo-fascism (Franco Freda,

Pino Rauti, and Enzo Erra of the New Order Studies

Center) to those represented by members of the more moderate right (Giano Accame, Marcello Veneziani).

Evola was also considered one of the main ideologues of the terrorist far right

during the Years of Lead 4 and his works are also appreciated by some fringes

of Islamic fundamentalism 5 Evola is also a popular author, largely due to his

metaphysical, magical, and supernatural beliefs, including belief in ghosts,

telepathy, and alchemy. His works are translated and published in Germany,

France, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Greece, Switzerland, Great Britain, Russia,

United States, Mexico, Canada, Romania, Argentina, Brazil, Hungary, Poland,

Turkey.6

When Evola’s ideas

are undergoing a revival, topics like these take on more than academic

significance.7 The entwinement of biological and spiritual beliefs about race

is not a thing of the past, no minor concern in light of the porous boundary

between putatively extremist ideologies and the cultural mainstream.8 Evola’s

project may have failed in its era. Still, the resentments that animated it has

by no means disappeared. Critical scholarship on allegedly ancient racial myths

and their modern implementation can help clarify our understanding of a history

that has lost little of its relevance. Opaque as they may seem to contemporary

observers, Evola's theories espoused in a fateful interchange between Nazi

Germany and Fascist Italy deserve renewed attention today.

Enter Steve Bannon

In an article

titled "how

a mystical doctrine is reshaping the right" Steve

Bannon, Russia’s Alexander Dugin, and Brazil’s Olavo de Carvalho are

united by their affinity with a spiritual movement that fundamentally rejects

modernity.

The same as also in

Austria and other countries worldwide Alexander Dugin met

with members of the National Front and Austria’s Freedom Party.

Near the end of this

investigation, I also was able to read the book by Benjamin R. Teitelbaum

of which the Sept/Oct 2021 issues of Foreign Affairs reports that: Seeking

to understand the roots of Bannon’s eccentric post-fascist beliefs, Teitelbaum

(a music professor who also studies radical populists) convinced him to sit for

20 hours of interviews. Teitelbaum sets out to find the leaders of Bannon’s

underground “spiritual school” committed to “Traditionalism,” a secretive

ideology that rejects modernity, the Enlightenment, materialism, and

globalization. They include a bearded supporter of Russian President Vladimir

Putin who promotes “Eurasianism” as an alternative to

the rotten West, the former leader of a Hungarian nationalist and anti-Roma

party, an Iranian American author peddling plans for a eugenic purification of

Persians, a Brazilian philosopher active on social media and close to Brazil’s

current populist government, and a Briton with obscure corporate and political

connections and the code name “Jellyfish.

Teitelbaum, who

kept an exact diary of all of his meetings with Bannon inclusive pictures taken

with both him and Bannon on

it, focuses particularly on the year 2018. He also describes

going to a bookstore with Bannon where the latter bought a copy of H.P.

Blavatsky's Occult primer "The Secret Doctrine," a book we have

actually already had extensively covered in our extensive

archive of older articles here.

Teitelbaum also

mentioned that 'Steve told me, he connected with University of San

Francisco philosophy professor Jacob Needleman: a scholar knowledgeable,

as Teitelbaum mentions, of Rene Guenon. It is

widely known that Dugin’s worldview fuses a revived pan-Slavism (the

ideology that helped trigger Europe’s fratricidal explosion in 1914) with more

cosmopolitan fascist currents, particularly the so-called Traditionalism of

René Guénon and Julius Evola. In

fact, Guénon’s main disciple was indeed

Julius Evola the leading inspirator for Dugin's Eurasianism, which

various news sources mentioned was cited by Bannon including the NYT with Steve

Bannon Cited Italian Thinker Who Inspired Fascists.

War for

Eternity joins the dots between this newly influential philosophy and

leading personalities from the global right. In 2018-9 Teitelbaum spent 20

hours talking to Bannon. He spoke to Dugin and met with Olavo de

Carvalho, a one-time

journalist and astrologer who advises Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro.

Dugin and his many

accolades to which according to the well-researched book

by Teitelbaum, thus attempt to pursue a multiform strategy on the

fringe of the classical electoral political spectrum. He develops a

geopolitical discourse aimed at a large public, a concept of Eurasia as the

basis for a new ideology of Russian great power for the Putin establishment,

and Traditionalism and other philosophical and religious doctrines restricted

to small but influential and consciously elitist intellectual circles.

As we have seen

above, the simplest way into Traditionalism is to think of it as the fourth

quadrant on a political compass where the other three are fascism, liberalism,

and communism. Traditionalism rejects all three rivals on the same grounds that

they are modernist, they’re competing for the chance to modernize the world;

and they’re materialist: communism and liberalism are both obsessed with money,

fascism with bodies.

And though Teitelbaum

begins and ends with Bannon and Dugin, we can see this hunger for the end of

the world far beyond the bounds of his book, in the spiritualized contrarianism

of Peter Thiel; in the neo-reactionary movement, which calls for the end of

democracy; and in the watered-down religious traditionalism of pop gurus such

as Jordan Peterson, whose dragon-slaying rhetoric and imagery hearken back to a

mythic, imagined time of heroes and demigods: primal figures free of the

atrophy of modern urban society.

US President Donald

Trump (L) congratulates Senior Counselor to President Stephen Bannon during the

swearing-in of senior staff in the East Room of the White House on January

22, 2017, in Washington, DC:

The drama of War

for Eternity culminates in the meeting of Bannon and Dugin in Rome only a

few blocks from Evola’s former apartment, where Bannon solicits the Russian’s

opinions of Heidegger before attempting to persuade him to join some united

global Traditionalist front. “We were born into nothingness, Mr. Bannon,” the

Russian reflects. “And yet we each found our way to it,” Bannon responds. “The

Tradition.”

In the end,

however, Teitelbaum's book is good on Bannon but weak on Dugin's wider

background including missing is Russian history and its relevant political

inclinations during the various time periods we instead have detailed in the

above earlier part of this by now extensive investigation.

In his recent

book The Decadent Society, Ross Douthat identifies the fundamental problem

of our age not as libertinage but as disaffection: Ours is a world in which the

political landscape has been reduced to “a kind of digital-age playacting in

which young people dissatisfied with decadence pretend to be Fascist and

Marxist on the Internet, reenacting the 1930s and 1960s with fewer street

fights and more memes.” If this is so, then the Duggins and the Bannons of the world are the biggest play-actors of all:

reenacting the twilight of the gods, just with more memes.

Even

if Dugin’s institutional presence in Russia and all the countries we

mentioned, including the USA, is based on groupuscules, the influence of his

personality and his works must not be underestimated. Despite his rhetorical

radicalism, which few people are prepared to follow in all its philosophical

and political consequences, Dugin has become one of the most

fashionable thinkers of the day. Using networks that are difficult to trace, he

disseminates the myth of Russian great power, accompanied by imperialist,

racialist, Aryans, and occultist beliefs expressed euphemistically

and whose scope remains unclear, but that cannot remain without

consequences. Dugin’s role as an ideological mediator will probably

be an important point to consider in any long-term historical assessment: he is

one of the few thinkers to engage in a profound renewal of Russian nationalist

doctrines, repetitive in their Slavophilism and their czarist and/or Soviet

nostalgia. His originality lies precisely in his attempt to create a revolutionary

nationalism refreshed by the achievements of 20th-century Western thought,

fully accepting the political role these ideas played between the two world

wars. Therefore, in his opposition to American

globalization, Dugin unintentionally contributes to the

internationalization of identity discourse and the uniformization of those

theories attempting to resist globalization. He illustrates that, although

aiming for universality, these doctrines are still largely elaborated in the

West. This is a paradoxical destiny for a Russian nationalist,

whose self-defined and conscious “mission” is to anchor a profoundly

Western intellectual heritage in Russia and to use it to enrich his fellow

citizens.

And not to mention

that he is a charmer Russian President Vladimir Putin danced arm-in-arm

with Austria's foreign minister, Karin Kneissl:

Germany ueber alles?

One must note the

paradoxical absence of Germany. While German thought from the early twentieth

century and the interwar years comprises one of the core tenets of Dugin’s

doctrine, he has few allies in Germany, compared with his deep interactions

with the Francophone world and the Mediterranean. His German acquaintances have

only very recently been cultivated, namely with the journal Zuerst,

launched in 2010 as the successor of the neo-Nazi Nation and Europa to promote

right-wing thought in Germany. Zuerst! prominent

journalist Manuel Ochsenreiter, has interviewed Dugin

several times. Thanks to this network, Dugin was invited to join the March 2015

conference of far-right thinkers and activists organized by Dietmar Munier, who

owns the two biggest far-right publishing houses in Germany, Arndt and Lesen and Schenken, Although

Dugin has read and sometimes cited Armin Mohler, a disciple of Ernst Junger and

Swiss-born far-right political writer and philosopher, known for his works on

the Conservative Revolution and associated with the Neue

Rechte, the two men do not appear to have met.

But France Yes

Back in 2011, Marine

Le Pen acknowledged admiring the Russian president and supporting Russia:

‘"I can only be concerned when I see that our president [then Nicolas

Sarkozy], at the instigation of the Americans, is turning his back on Russia.

Following the Americans, the French media demonizes Russia.'] The FN insists on

several positive components of the Russian regime: authoritarianism (the cult

of the strong man), anti-American jockeying (the fight against U.S. unipolarity

and NATO domination), defense of Christian values, rejection of gay marriage,

criticism of the European Union, and support for a “Europe of Nations.” With

Russia's international condemnation after the Ukrainian crisis, Marine Le Pen

has turned out even greater praise: “Mr. Putin is a patriot. He is attached to

the sovereignty of his people. He is aware that we defend common values. These

are the values of European civilization. ”[] She, therefore, calls for an

“advanced strategic alliance” with Russia, which should be embodied in a continental

European axis running from Paris to Berlin to Moscow. Regarding the Ukrainian

crisis, the FN totally subscribes to the Russian interpretation of events and

has given very vocal support to Moscow's position. The party criticized the

Euro-Maidan revolution, thinks that the EU “threw oil on the fire” by proposing

an economic partnership with a country in which half the population looks to

the East, states its preference for a federalization of Ukraine that would give

a broad autonomy to the Russian-speaking regions, and supports Russian

proposals for solving the Donbas conflict.

The FN has become increasingly

active in its relations with Russia, including several trips by high-ranking

leaders: Marion Marechal-Le Pen, Marine’s niece, and France's youngest MP,

traveled there in December 2012; Bruno Gollnisch,

executive vice president of the FN and president of the European Alliance of

National Movements (AEMN), went in May 2013; and Marine Ee Pen and FN vice

president Louis Aliot both went in June 2013. During

the second trip in April 2014, Marine Le Pen was received at a high political

level by the president of the Duma, Sergei Naryshkin, the head of the Duma’s

Committee on Foreign Affairs, Aleksei Pushkov, and

the deputy prime minister, Dmitri Rogozin.

Several Russophile

figures surround the president of the FN and have enhanced the party’s

orientation toward Russia. The most famous is Aymeric Chauprade.

an FN international advisor and European deputy who is close to Konstantin

Malofeev. Next comes Xavier Moreau, a former student of Saint-Cyr, France’s

foremost military academy, and a former paratrooper, who directs a Moscow-based

consulting company, Sokol, and seems to play a central role in forming

contracts between FN-friendly business circles and their Russian counterparts.

Fabrice Sorlin, head of Dies Irae, a fundamentalist

Catholic movement, leads the France- Europe Russia Alliance (AAFER). The FN

also cultivates relations with Russian emigre circles and institutions

representing Russia in France. The FN’s two MPs, Marion Marechal-Le Pen, and

Gilbert Collard are both members of a France-Russian friendship group. Marine

Le Pen seems to have frequently met in private with the Russian ambassador to

France, Alexander Orlov who chairs the board of Gazprom-Nord Stream. These

alliances weakened during the Ukrainian crisis, given Chancellor Angela

Merkel’s leading role in condemning Russia. But some new friends emerged among

Die Linke, a powerful post-communist party in former East Germany.

In addition to the

political networks, there is a powerful and well-structured net of “civil

society” organizations and think tanks that promote Russian interests. The most

well-known among them is the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation (IDC), led

by Natalia Narochnitskaya, a high priestess of

political Orthodoxy since the 1990s and former member of parliament (MP) in the

Russian Duma. John Laughland, the Eurosceptic British historian and frequent

commentator on the Russian-funded television network RT, is director of studies

at the IDC, which is funded by Russian “charitable NGOs” (non-governmental

organizations). The Russian government makes use of the long-established

cultural institutions associated with the presence of an important Russian

diaspora in France that dates back to the 1920s and the Soviet period. It

contributes to a myriad of Russian associations such as the Dialogue

Franco-Russe, headed by Vladimir Yakunin, who was head of Russian Railways and

a close Putin adviser until August 2015, and Prince Alexandre Troubetzkoy, representative of the Russian emigration.

Paris is also home to the largest Russian Orthodox Church in Europe, which

opened in fall 2016 in the center of Paris. The Moscow Patriarchate’s close

relationship with the Kremlin helps project Russia’s “soft” power in Europe.9

Russia’s Calibrated Tools

Today Russia is

successfully manipulating the asymmetrical soft power tools. It has joined lip

with new allies that no longer represent the same ideological values as those

from the Soviet years.

Adept at realpolitik,

Moscow plays the game it thinks is best adapted to Russia’s current situation.

It has cultivated the distinct interests of some EU member states to weaken the

European construct, reduce Europe's attractiveness to the peripheries that

Europe and Russia share, and create new allies among the most fragile or

disgruntled countries within anti-mainstream movements.

However, the partial

overlap of the European networks of Dugin, for some of them built more than

twenty years ago. Those elaborated by the Kremlin since the mid-2000s are cause

for significant concern. s are those of the European New Right, rooted in barely

concealed fascist traditions. Some assumed intellectual and individual

affiliations with the Nazi ideology and post-Nazi elusive transformations. On

the contrary, the Kremlin has progressively created a consensual ideology with ut doctrine, founded on Russian patriotism and classical

conservative values: respect for hierarchy, established social order,

authoritarian political regime, the traditional family, etc. At first glance,

classic conservatism and a far-right inspired by a fascist heritage share little

in common. Classic conservatism does not reject Enlightenment values but seeks

more gradual social and political evolution and an end to the cult of progress

and individualism at any cost; far right is thoroughly anti-Enlightenment,

calling for the return to medieval orders and make inequality among men one of

its founding principles.

The Kremlin seeks to

establish a brand for Russia that depicts it as a torchbearer of European

traditions and as a power challenging the post-war liberal-democratic status

quo. It hopes for a mythical Paris-Berlin-Moscow axis. However, it has not

extensively recruited in classical conservative circles (e.g.. the CDU/CSU in

Germany, the UMP in France, and the Conservative party in the UK) except in

Hungary with Fidesz, but rather among the more extreme fringes. Despite an

ideology of stability, the Kremlin cooperates with twilight ideologies. Does

this mean that Russia could not find any allies in conservative European

circles and had no choice but to consolidate ties with the only groups ready

for a tactical alliance with Moscow, i.e., the far-right? If so, how were the

contacts made? The parallels between the networks of Dugin and the Kremlin are

not systematic, but they are prevalent. For example, almost all European

observers who validated the referendum in Crimea can be placed on the extreme

right of the political spectrum, whether or not they have been in direct

contact with Dugin before. In the Malofeev-sponsored meeting in Vienna, s and

those of the Kremlin appear to form a single ecosystem.

Who is thus mimicking

whom? Who usurped the contacts of the other? Is Dugin directly “feeding” the

Kremlin with contacts with European far-right circles? His European

acquaintances predate those of the Kremlin. Still, this explanation seems

short-sighted, knowing that Dugin is not well connected to the presidential

administration, contrary to what Western pundits tend to assume. Dugin is no

more than one among many other mediators who can offer the Kremlin some bridges

to European fellow travelers, and some are better connected than he: Natalia Narochnitskaya in Paris; Dmitri Rogozin, Russia’s former

ambassador to NATO and current deputy prime minister, whose Rodina party has

been very Westward-looking in terms of ideological inspirations; and Konstantin

Malofeev, who is linked to the Church’s networks in Europe around abortion and

anti-gay slogans.

The fact that s and

those of the Kremlin overlap are not sufficient to prove that they are being

articulated by the same forces, according to unidirectional, top-down dynamics.

This more logically demonstrates that Putin had few friends in Europe and fewer

since the events in Ukraine. This limited pool

This has facilitated

the overlap between different networks built by groups with originally

diverging sensibilities and ideological agendas. The Russian presidential

administration targets more populist and mainstream parties, while Dugin’s

contacts are more radical and marginal.

The reasons for this

honeymoon between Russia and European far-right circles are primarily

ideological. Both seek allies against the mainstream and identify themselves as

outsiders challenging the “center,’' or what they often name “the system.”

Their enemies have clearly been identified.

Conclusion

Traditionalism is a

radical doctrine, so radical that scholars of the far-right had often dismissed

it as an obscure curiosity devoid of high-level political consequence. Some of

its early right-wing adherents believed a race of ethereal Aryans once lived in

the North Pole and advocated establishing celibate patriarchy of

warrior-priests in place of democracy. It often sounds more like make-believe

than politics; Dungeons and Dragons for racists, as a former student of mine

once put it.

But dismissing

Traditionalism is no longer an option, now that Dugin and his ilk are gaining

exceptional influence throughout the globe. These ideologues infused a major

political party in Hungary, Vladimir Putin’s government, and later Donald

Trump’s and Jair Bolsonaro’s administration through figures like Steve Bannon

and Olavo de Carvalho, a renegade astrologer and philosopher who advises the

Brazilian government on foreign and domestic policy.

Milo Yiannopoulos and

Allum Bokhari, in a 2016 Breitbart article titled “An Establishment Conservative’s Guide to

the Alt-Right,” introduced the alt-right as a subversive movement borne out of

the internet. Yiannopoulos and Bokhari present alt-right activists as

“intellectuals.” Nothing falls from the sky: There must be functional roots to

such an intellectual movement, and there must be an active, stable nucleus that

develops and deploys its ideology to galvanize followers and sympathizers.

Yiannopoulos and

Bokhari also mention Julius Evola, among others, as a thinker who inspired the

origin of the alt-right. Dugin, however, was fascinated with Evola long before

the alt-right. As Dugin admits in an interview, Evola’s “readings changed my life.” The early roots

of Dugin’s fascist ultra-nationalism can therefore be found in the late 1960’s

French political movement, the Nouvelle

Droite, or the New Right.

Aleksandr Dugin and his contemporary Aleksandr Panarin had close

ideological ties with

the European New Right.

In their

article, Yiannopoulos

and Bokhari highlight

the alt-right assault on Western liberalism and democracy. In its place, the

alt-right wants “natural instincts, tribal psychology, and identity politics:

the preservation of tribe and its culture.” This overall idea can be found

in Dugin’s work: “liberal individualism is destructive and criminal.

It separates individuals from their collective identities.” According to

Yiannopoulos and Bokhari, the alt-right aims to build “homogenous communities

to preserve traditional identities: a separation from liberal cultures.”

Dugin’s outrage over neoliberalism underlines all of these ideas.

What we have seen in

the course of the above article is that particular elements of the far

right-sided with Russia, and then explores how the far-right pro-Russian

attitudes developed in the West during the Cold War, as well as pointing out

that Soviet Russia was often prone to use the Western for the right for its own

political benefits. They facilitated and contributed to the deepening of the

relations between Russian pro-Kremlin actors and the Western far-right when

more favorable conditions arose in the second half of the 2000s. And how

particular elements of the Western far right embraced it including openly

pro-Russian activities that European far-right movements and organizations have

carried out in their national contexts. This included far-right

politicians on high-profile discussion platforms in Moscow and at sessions of

the European Parliament in Strasbourg and Brussels.

The relative

obscurity of Dugin’s work in Western countries may have kept these links vague,

but the fingerprints of Eurasanism are visible. Dugin

celebrated the

union between Italy’s far-right League party and the populist Five Star

Movement, claiming that Matteo

Salvini’s government was

the first concrete expression of his visions. To understand the wider

ideological context of the contemporary radical right, it is imperative to

identify the shadowy hand of the Global Revolutionary Alliance. A suitable

signpost can be, “Beware of preachers of Duginism.”

Russia’s network of

influence has reached far beyond the vulnerable states of post-socialist

Europe. Western countries and political leaders are not immune from the

Kremlin’s efforts. While there is no single formula for how Russia seeks to

exert and project its power in Europe’s core, the goal of the Trojan Horse

strategy is the same: to build a web of allied political leaders and parties

who will legitimize Russia’s aims to destabilize European unity and undermine

European values. Ironically, while the Ukraine crisis has united Europe and the

United States around a cohesive sanctions policy on Russia, it has also

incentivized Putin to intensify efforts to infiltrate European polities by

cultivating Trojan Horses in an effort to weaken Europe’s resolve.10

What can also be said

is that the various non-Russian Western and Eastern sources of “neo-Eurasianism,” as well as the flexibility of its geographic

orientation and practical implications, are among the reasons why Dugin and his

various organizations have been able to develop especially far-reaching

international ties in Europe and Asia. In recent years, Dugin & Co. have

actively participated not only in creating contacts between various radical

nationalists in Western and East-Central Europe, on the one side, and Russia,

on the other. As indicated in, among other investigations, Anton Shekhovtsov’s seminal 2017 monograph Russia and the

Western Far Right, Dugin’s

extensive networks in the West have also played a certain role in establishing

links between representatives of the Putin regime (politicians, diplomats,

propagandists, etc.) with far-right forces in the EU, United States, Turkey,

and other countries.

1. For details of

this period see Julius Evola: Un filosofo in guerra. 1943-1945 di Gianfranco de Turris, 2017.

2. Alberto Spektorowski, “The Intellectual New Right, the European

Radical Right and the Ideological Challenge to Liberal

Democracy,” International Studies 39, no. 2 (2002): 169.

3. Gianfranco De Turris,

La corrispondenza tra Julius Evola e Gottfried Benn, su centrostudilaruna.it,

2008.

4. Payne, Stanley, A

History of Fascism, 1914-1945, University of Wisconsin Pres., 1996, ISBN

978-0-299-14873-7.

5. Diego Gambetta,

Steffen Hertog, Engineers of Jihad: The Curious Connection Between Violent

Extremism and Education, Princeton University Press, 2016, pp. 88, 97.

6. Gianfranco De

Turris, Profilo di Julius Evola, in Julius Evola,

Rivolta contro il mondo moderno,

4ª ed., Roma, Mediterranee, 2008. ISBN

978-88-272-1224-0 Bibliografia.

7. On Evola’s current

influence cf. Andrea Mammone, Transnational Neofascism in France and Italy

(Cambridge2015), 62-78, 84-90, 167-71; Charles Clover, Black Wind, White Snow:

The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism (NewHaven, CT

2016), 158-60, 173-79; Jason Horowitz, “Steve Bannon Cited Italian Thinker Who

Inspired Fascists” New York Times (12 February 2017); Jean-Yves Camus and

Nicolas Lebourg, Far-Right Politics in Europe

(Cambridge, MA 2017), 144-49; Thomas Main, The Rise of the Alt-Right

(Washington, DC 2018), 216-21.

8. For perceptive

reflections on this dynamic, see David Roberts, ‘How not to Think about Fascism

and Ideology, Intellectual Antecedents and Historical Meaning,’ Journal of

Contemporary History, 35 (2000), 185-211; FrancescoGerminario,

Argomenti per lo sterminio:

Stereotipi dell’immaginario

antisemita (Turin 2011), 282-306; AristotleKallis,

‘When Fascism Became Mainstream: The Challenge of Extremism in Times of

Crisis’, Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies, 4 (2015), 1-24.

9. Andrew

Higgins, “In Expanding Russian Influence, Faith Combines with

Firepower,” New York Times, September 13,

2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/14/world/europe/russia-orthodox-church.html?_r=0.

10. Russia’s network

of influence has reached far beyond the vulnerable states of post-socialist

Europe. Western countries and political leaders are not immune from the

Kremlin’s efforts. While there is no single formula for how Russia seeks to

exert and project its power in Europe’s core, the goal of the Trojan Horse

strategy is the same: to build a web of allied political leaders and parties

who will legitimize Russia’s aims to destabilize European unity and undermine

European values. Ironically, while the Ukraine crisis has united Europe and the

United States around a cohesive sanctions policy on Russia, it has also

incentivized Putin to intensify efforts to infiltrate European polities by

cultivating Trojan Horses in an effort to weaken Europe’s resolve.

For updates click homepage here