By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

Past Changes, Future Problems

The economic news

from Europe over the past month has been bleak. Throughout the eurozone, gross

domestic product is either stagnant or in decline. Business surveys from

September show that Germany’s economy – the engine of the European Union – has

entered recession as it struggles with high energy costs and weak industrial

output. Reports about intensified Russian attacks on Ukrainian port

infrastructure will only make matters worse, especially as the conflict in the

Middle East escalates. Spikes in the price of energy and food cannot be ruled

out.

And yet, the

underlying issues facing the global economy stem from deeper challenges, which

owe partly to the way the global economy has changed over the past few decades.

These changes highlight the structural vulnerabilities in international trade

systems and supply chains that were established long before the current crises.

In Europe, the

biggest change after the Cold War ended was deindustrialization. After China

joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, European companies raced to

outsource their manufacturing to countries with lower labor costs. Europe’s

industry has since suffered greatly, especially in sectors that are

energy-intensive – a problem that has only intensified since Russia’s invasion

of Ukraine in 2022. The surge in energy prices that year has since declined,

but executives in the chemicals, steel and aluminum industries argue that

European competitiveness has yet to recover. While Europe has been working to

switch from natural gas to liquified natural gas, this conversion in

energy-intensive sectors is not only expensive but also sometimes difficult, if

not impossible. (For example, while steel production using LNG is possible, it

is not very effective.) Compounding the problem is that the wars to the east

and southeast have compelled Europe to strengthen its military capabilities. To

do that, Europe must prioritize the rehabilitation of these crucial industries,

focusing on reindustrialization as a strategic imperative that will benefit its

economies and defenses alike.

Naturally, this is

easier said than done. Rising energy and labor costs have dramatically cut

European manufacturing. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, there has

been a sharp decline in such key industries as cars, chemicals, textiles,

electronics and food processing throughout the European Union. The bloc’s share

of global gross value added fell to a low of just over 13 percent, according to

Eurostat. By 2022, that

number had climbed back to 15 percent – lower than its peak in the mid-1990s

but still the highest it has been since 2004.

Reindustrialization

will require significant investment, especially in areas vital to economic

resilience and strategic independence. The COVID-19 pandemic (and its economic

discontents) added a new sense of urgency to efforts to restore businesses as a

way to mitigate the risks inherent to global supply networks. Thus, since 2020,

foreign direct investment in Europe has grown, with an important rise in

cross-border investment projects, notably in the EU's manufacturing sector.

(There was a temporary drop after Russia invaded Ukraine.)

Even so, the costs of

reshoring are considerable, particularly in industries where governments do not

provide incentives. There’s plenty of data to suggest that FDI has expanded

most in sectors where authorities give more assistance, especially for megaprojects

in strategically critical industries such as semiconductors, electric vehicles

and pharmaceuticals. But state support is not enough. True reindustrialization

requires more than just money; it needs strong infrastructure, skilled labor,

raw materials, energy and a well-developed industrial ecosystem – measures that

go beyond incentives and introduce ways to support small and medium-sized

enterprises and innovation that could contribute to improving the business

environment as a whole. Without addressing these issues, FDI projects risk

falling short of their potential to contribute meaningfully to

reindustrialization.

One thing Europe (and

others) has going for it is that even before the pandemic (while investment was

low) companies had already undertaken other efforts to mitigate supply chain

risk, including global free zones and special economic zones – designated areas

within countries that offer businesses advantages such as reduced taxes,

relaxed regulations and streamlined customs processes. These zones tend to

attract FDI because they provide a highly favorable environment for

manufacturing, trade and logistics. And since they are often located

strategically near trade routes, ports and airports, they also tend to reduce

operational costs, increase market access and enhance business flexibility.

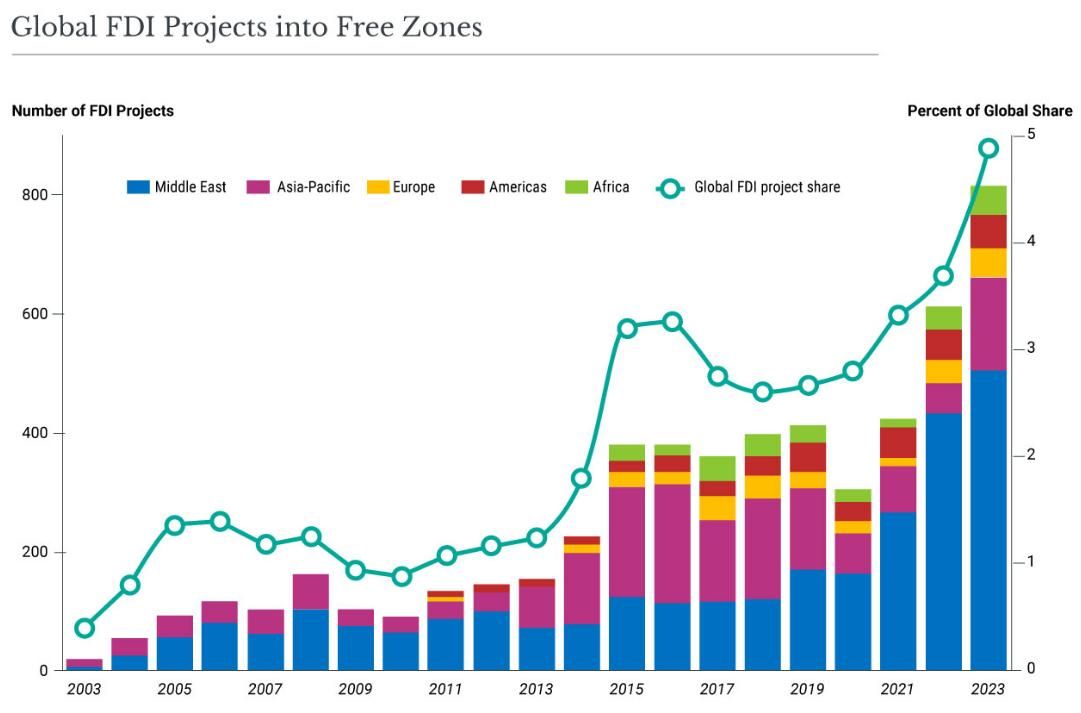

It should come as no

surprise, then, that global free zones attracted record-breaking FDI in 2023,

accounting for nearly 5 percent of all FDI projects worldwide. It’s unclear

exactly how many such zones there are globally – estimations vary depending on governance,

incentives, target sectors, services offered and, critically, the organization

reporting the number – but most reports

note a trend toward “new-generation zones,” which are usually bigger, more integrated with

local economies and less reliant on fiscal incentives than earlier zones. What

is clear is that Europe has significantly fewer SEZs than Asia and Africa.

European SEZs are more regulated and less incentivized, and they often target

high-value businesses such as technology, pharmaceuticals and sophisticated

manufacturing. Thus as state-incentivized cross-border investments expanded in

Europe, so did investments in European SEZs.

State inducements

aside, the growing trend of SEZs in Europe can also be attributed to the

geopolitical risks that have reshaped global trade routes. The Northern

Corridor, which passes through Russia, is not used nearly as much as it once

was, thanks to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Trade via the world’s oceans

and the Red Sea, meanwhile, has similarly become an unreliable security risk.

This has opened up opportunities for the Middle

Corridor, a route connecting

Europe and Asia through the Caucasus and Central Asia whose traffic doubled

from 2022 to 2023 compared with pre-pandemic data.

But there are several

problems that must be addressed before the corridor realizes its potential.

It's fraught with logistical and infrastructural obstacles, including

inefficiencies in port operations, underdeveloped rail systems and bottlenecks

at key border crossings. It is also comparatively primitive, so the limited

exchanges of digitized data hampers cargo movement, contributing to delays and

increased costs. If the Middle Corridor is to be globally competitive, it will

require a substantial amount of investment and even more cooperation among the

states through which it passes. Problematically, most of these countries are in

Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Black Sea region, which can have wildly

different priorities and ideas on how to capitalize on infrastructure

investment.

The EU will have to

be proactive to make sure the trade route is reliable and efficient and aligns

with its interests. To that end, it has already taken diplomatic steps to

maintain dialogue with Central Asian countries and has promised to invest in

the Middle Corridor, especially its railways. But improving port operations in,

say, Georgia and Turkey, may be beyond the EU’s control. Not only are they not

members of the EU, but recently, they have been turning away from the West and

even been at odds with the bloc, becoming recipients of Chinese investment, at

least as far as port infrastructure is concerned.

To some degree or

another, the success of the Middle Corridor will be determined by the security

of the corridor’s entry point to Europe: the Black Sea. The sea houses several

SEZs along its coast that facilitate – and, if things are going well, enhance –

regional trade. The corridor may be able to function, but it will never be able

to thrive, let alone integrate with European supply chains, unless Europe can

ensure freedom of navigation and safeguard Black Sea shipping routes. This is

why Brussels seems to have prioritized working on maritime security there and

has become so focused on its military capabilities.

To keep the Black Sea open and free, the

EU will have to closely collaborate with NATO, which also has a strategic

interest in Black Sea stability. However, Turkey – a NATO member – tends to

pursue a more autonomous foreign policy. Unlike many others in the group, it

maintains relations with Russia and has strengthened economic ties with

China, making it a pivotal but difficult partner for the EU and NATO.

Ideally, the EU would be able to engage in nuanced diplomacy, leveraging

Turkey’s position in the Middle Corridor while addressing divergent foreign

policy goals. However the EU policy is compromised by member states that have

their foreign policy agendas, which will make the promotion of the Middle

Corridor even more difficult.

And there’s not much appetite for difficulty right

now. European businesses’ inclination toward SEZs, which rely on the largesse

of their respective governments, reflects a growing caution about escalating

geopolitical risks. When businesses are squeamish, it usually indicates a

belief that global tensions will continue to rise, not fall. This bodes ill for

a continent trying to develop a cohesive economic strategy that at once

reindustrializes its economies and improves its defensive posture within NATO.

For updates click hompage here