By Eric Vandenbroeck and co-workers

We have seen survival and reproduction.

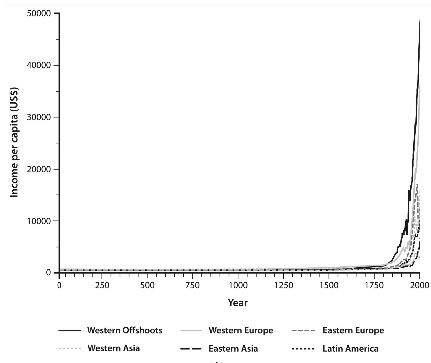

Living standards bordered on the subsistence level and scarcely varied over

millennia. We have experienced a dramatic improvement in the quality of life.

Most people a few centuries ago led lives comparable to those of their

remote ancestors – and most other individuals around the globe – millennia ago,

rather than to those of their current descendants. The living conditions of an

English farmer at the turn of the sixteenth century were similar to those of an

eleventh-century Chinese serf, a Mayan peasant fifteen hundred years ago, a

fourth-century BCE Greek herder, an Egyptian farmer 5,000, or a shepherd in

Jericho 11,000 years ago. But since the dawn of the nineteenth century, a split

second compared to the span of human existence, life expectancy has more than

doubled, per capita incomes have soared twenty-fold in the most developed regions

of the world and fourteen-fold on Planet Earth as a whole.

Over the past two centuries, the dramatic spike in income per capita

across world regions follows thousands of years of stagnation.

Which is to say, the entirety of human history up until the recent

dramatic leap forward – the fruits of technological advancements were channeled

primarily towards larger and denser populations and had only a glacial impact

on their long-term prosperity. People grew while living conditions stagnated

and remained near subsistence. Variations between regions in terms of the

sophistication of their technology and the productivity of their land were

reflected in differing population densities. Still, the effects they had on

living conditions were largely transitory. Ironically, however, just as Malthus

completed his treatise and pronounced that this ‘poverty trap’ would endure

indefinitely, his identified mechanism suddenly subsided, and the metamorphosis

from stagnation to growth took place.

How did the human species break out of this poverty trap? What were the

underlying causes of the extent of this epoch of stagnation? Might the forces

that governed both the protracted economic ice age and our escape from it

foster our understanding of why current living conditions are so unequal

globally?

It demonstrates how these forces operated relentlessly, if invisibly,

throughout human history, and its long economic ice age, gathering pace until,

at last, technological advancements in the course of the Industrial Revolution

accelerated beyond a tipping point, where rudimentary education became

essential for the ability of individuals to adapt to the changing technological

environment. Fertility rates started to decline, and the growth in living

standards was liberated from the counterbalancing effects of population growth,

ushering in long-term prosperity that continues to soar in the present day.

The impact of the growth process on environmental degradation and

climate change raises significant concerns as to how our species might live

sustainably and avert the catastrophic demographic outcomes of the past. The

journey of humanity provides a hopeful outlook: the tipping point that the

world has recently reached, resulting in a persistent decline in fertility

rates and the acceleration of ‘human capital formation and technological

innovation, could enable humanity to mitigate these detrimental effects and will

be central for the sustainability of our species in the long run.

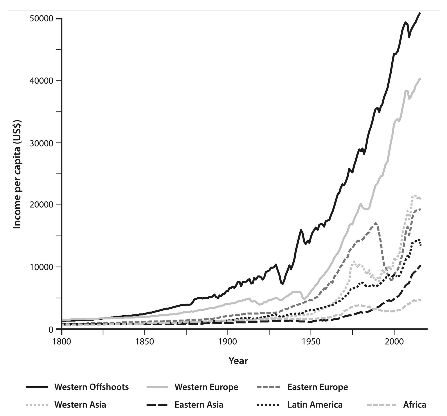

Intriguingly, when prosperity skyrocketed in recent centuries, it did

so only in some parts of the world, triggering a second major transformation

unique to our species: the emergence of immense inequality across societies.

One might suppose that this phenomenon occurred primarily because the escape

from the epoch of stagnation has happened at different times across the globe.

Western European countries and some of their offshoots in North America and

Oceania experienced the remarkable leap in living conditions as early as the

nineteenth century. At the same time, this ascent was delayed in most regions

of Asia, Africa, and Latin America until the latter half of the twentieth-century.

But what accounts for some parts of the world undergoing this transformation

earlier than others?

The divergence in per

capita income across world regions in the past two centuries.

Yet, deeper factors, rooted in the distant past, often underpinned the

emergence of cultural norms, political institutions, and technological shifts,

governing the ability of societies to flourish and prosper. Geographical

factors, such as favorable soil and climatic characteristics, fostered the

progression of growth-enhancing cultural traits – cooperation, trust, gender

equality, and a future-oriented mindset. Land suitability for large plantations

contributed to exploitation and slavery and the emergence and persistence of

extractive political institutions. The disease environment adversely affected

agricultural and labor productivity, investment in education, and long-run

prosperity. And biodiversity that invigorated the transition to sedentary

agricultural communities had beneficial effects on the process of development

in the pre-industrial era. However, these favorable forces have dissipated as

societies transitioned to the modern era.

But there is an additional factor lurking behind modern-day

institutional and cultural characteristics that joins geography as a

fundamental driver of economic development – the degree of diversity within

each society, its beneficial effects on innovation, and its adverse

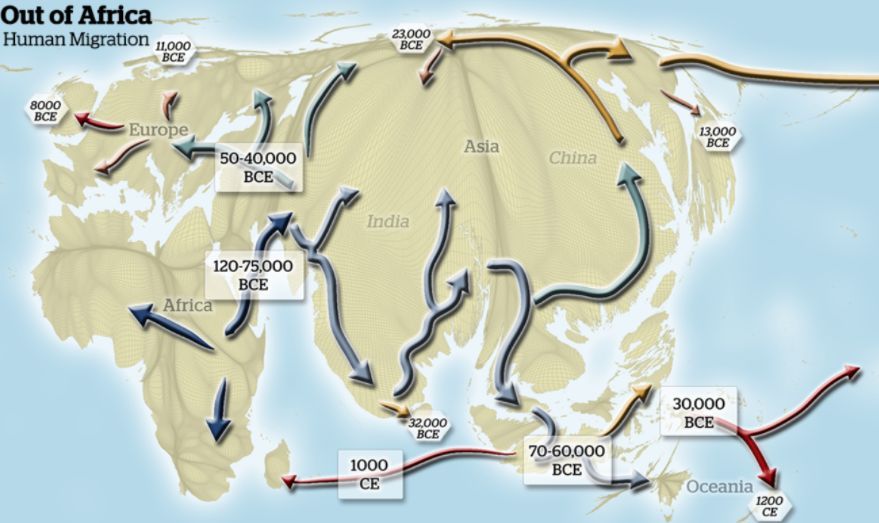

implications for social cohesiveness. Our exploration of the role of

geographical characteristics will take us 12,000 years back in time to the dawn

of the Agricultural Revolution. The examination of the causes and consequences

of diversity will lead us tens of thousands of years further back to the first

strides of our species out of Africa.

In the years that followed World War II, several facilities resembling

military airbases were built on the small island of Tanna

in the Pacific Ocean. These sites had planes, runways, watchtowers, and

headquarters and canteens – but none of them was real. The aircraft was made of

hollow tree trunks. The runways were insufficient to facilitate landings and

take-offs. The reed watchtowers housed monitoring devices carved out of wood,

and only flaming torches provided light. Although no planes had ever landed in

these fabricated airfields, some islanders imitated air traffic controllers

while others conducted military parades, carrying sticks instead of rifles. The

war had made a profound impression on the indigenous peoples of Tanna and other Melanesian islands across the Pacific. They

had witnessed the might of the industrial powers of Japan and the United

States, whose planes whizzed across the skies above their homes, whose ships

fired at each other in the surrounding ocean, and whose troops set up bases on

their islands. One phenomenon that made a particularly lasting impression on

the islanders was the bountiful cargo that these strangers brought with them:

crates of canned food, medicine, clothes, and a variety of equipment that the Tanna islanders had rarely encountered. When the war ended

and the troops returned home, the source of this bounty dried up. These

islanders, unfamiliar with the modern manufacturing process and seeking to

ascertain the provenance of this wealth, reproduced some of the features and

practices that accompanied it, hoping ultimately that the cargo – perceived

physical and spiritual wealth, equality, and political autonomy – might return

to bless their islands again.

Too often, Western policy recommendations for the development of poorer

nations are not that different from these ‘renewing rituals’ of the Tanna islanders. They involve a superficial imitation of

institutions that correlate with economic prosperity in developed countries,

without proper consideration of the underlying conditions that allow them to

generate wealth – circumstances that may not exist in the poorer countries. In

particular, the conventional wisdom has been that poverty in the developing

world is predominantly the result of improper economic and governmental

policies. It can therefore be eradicated by applying a universal set of

structural reforms. This presumption has been based on a fundamental

misconception since it ignores the critical impact of deep-rooted factors on

the efficacy of such policies. An effective strategy would grapple instead with

these primary factors as they are the ones that have invariably hindered the

growth process, and they often differ radically from one country to

another.

One conspicuous example of this misguided approach is the Washington

Consensus – a set of policy recommendations for developing countries focused on

trade liberalization, the privatization of government-owned enterprises,

greater protections for property rights, deregulation, broadening the tax base,

and reducing marginal tax rates. Despite intense efforts by the World Bank and

the International Monetary Fund to implement Washington Consensus–inspired

reforms in the 1990s, they have had limited success in producing the desired

results. Privatization of industry, trade liberalization, and secure property

rights might be growth-conducive policies for countries that have already

developed the social and cultural prerequisites for economic growth. Still, in

environments where these foundations are absent, where social cohesion is

tenuous and corruption well entrenched, such universal reforms have often been

fruitless.

No reforms, however efficient they may be, will transform impoverished

nations into advanced economies overnight because much of the gulf between

developed and developing economies is rooted in millennia-long processes.

Institutional, cultural, geographical, and societal characteristics that

emerged in the distant past have propelled civilizations through their distinct

historical routes and fostered the divergence in the wealth of nations.

Incontestably, cultures and institutions conducive to economic prosperity can

be gradually adopted and formed. Barriers erected by aspects of geography and

diversity can be mitigated. But any such interventions that ignore the

particular characteristics that have emerged throughout each country’s journey

are unlikely to reduce inequality and may instead provoke frustration, turmoil,

and prolonged stagnation.

The asymmetric effects of globalization and colonization are at the

outer layer of the roots of inequality. These processes intensified the pace of

industrialization and development in Western European nations while delaying

the escape of less-developed societies from their poverty trap. The persistence

of extractive colonial institutions in some regions of the world, designed to perpetuate

existing economic and political inequalities, exacerbated this gap in the

wealth of nations even further.

Nevertheless, these forces of domination, exploitation and asymmetric

trade during the colonial age were predicated on uneven development before the

colonial era. Pre-existing regional differences in political and economic

institutions and prevailing cultural norms had a governing influence on the

pace of development and the timing of the transition from stagnation to growth.

Institutional reforms at critical junctures in the course of human

history and the emergence of distinct cultural characteristics have

occasionally placed societies on diverging growth trajectories over time.

Nevertheless, random events – dramatic and substantial as they loom in our

minds – have played a transitory and primarily limited role in the progression

of humanity as a whole, and they are doubtful to be the dominating factors

behind the divergence in economic prosperity between countries and regions in

the past few centuries. It is not a coincidence that the first great

civilizations arose in fertile lands around major rivers, such as the

Euphrates, Tigris, Nile, Yangtze, and Ganges. No random historical,

institutional, or cultural developments could have triggered the formation of

major ancient cities far from water sources or developed revolutionary

agricultural technologies in the heart of the frostbitten forests of Siberia or

the middle of the Sahara Desert.

At the inner layer, deeper factors rooted in geography and the distant

past often underpinned the emergence of growth-enhancing cultural

characteristics and political institutions in some regions and growth-hindering

ones in others. In places such as Central America, land suitability for large

plantations fostered the emergence and persistence of extractive political

institutions characterized by exploitation, slavery, and inequity. In others,

such as sub-Saharan Africa, the disease environment contributed to lower

agricultural and labor productivity and delayed the adoption of more advanced

agricultural technologies, diminishing population density, political

centralization, and long-run prosperity. In more fortunate regions, favorable

soil and climatic characteristics triggered the evolution of cultural traits conducive

to development – a greater inclination towards cooperation, trust, gender

equality, and a stronger future-oriented mindset.

An appreciation of the long-lasting impact of geographical

characteristics led us 12,000 years back to the dawn of the Agricultural

Revolution. During this period, biodiversity, the availability of domesticable

species of plants and animals, and the orientation of the continents fostered

an earlier transition from hunter-gatherer tribes to sedentary agricultural

communities in some places and a later transition in others. Indeed, regions in

Eurasia where the Neolithic Revolution took place earlier enjoyed a

technological head start that persisted during the pre-industrial era. Notably,

however, the beneficial forces associated with this earlier transition to

agriculture dissipated in the industrial period and ultimately have played a

limited role in forging the vast inequality across the globe today; societies

who made the transition to agriculture earliest were not destined to become the

most prosperous nations in the present, as their agricultural specialization

eventually hindered the process of urbanization and mitigated their

technological head start.

Ultimately, the quest for some of the deepest roots of modern-day

prosperity led us further back to where it all began: the initial steps of the

human species out of Africa, tens of thousands of years ago. The degree of

diversity within each society, as determined partly by that exodus, has had a

long-lasting effect on economic prosperity over the entire course of human

history – with those who enjoyed the sweet spot of innovation-inducing

cross-fertilization and social cohesiveness benefiting most.

In recent decades, the rapid diffusion of development among poorer

countries has promoted the adoption of growth-enhancing cultural and

institutional characteristics in all regions of the world and contributed to the

growth of developing nations. Modern transportation, medical and information

technologies have diminished the adverse effects of geography on economic

development. The intensification of technological progress has further enhanced

the potential benefits of diversity for prosperity. Suppose these trends were

combined with policies that enabled diverse societies to achieve greater social

cohesion and homogeneous ones to benefit from intellectual cross-pollination.

In that case, we could begin to address contemporary wealth inequalities at

their very roots. Today on Tanna Island, one can find

an actual airport; primary schools are available for most children; islanders

own mobile phones; and streams of tourists, attracted by the Mount Yasur volcano and traditional culture, provide vital

revenues to the local economy. While income per capita in the nation of Vanuatu

to which the Island belongs is still very modest, it has more than doubled in

the past two decades. Despite the long shadow of history, the fate of nations

has not been carved in stone. As the great cogs that have governed humanity’s

journey continue to turn, measures that enhance future orientation, education,

and innovation, along with gender equality, pluralism, and respect for

difference, hold the key to universal prosperity.

In the years that followed World War II, several facilities resembling

military airbases were built on the small island of Tanna

in the Pacific Ocean. These sites had planes, runways, and watchtowers, as well

as headquarters and canteens – but none of them was real. The aircraft was made

of hollow tree trunks, the runways were insufficient to facilitate landings and

take-offs, the reed watchtowers housed monitoring devices carved out of wood,

and only flaming torches provided light. Although no planes had ever landed in

these fabricated airfields, some of the islanders imitated air traffic

controllers while others conducted military parades, carrying sticks instead of

rifles. The war had made a profound impression on the indigenous peoples of Tanna and other Melanesian islands across the Pacific. They

had witnessed the might of the industrial powers of Japan and the United

States, whose planes whizzed across the skies above their homes, whose ships

fired at each other in the surrounding ocean, and whose troops set up bases on

their islands. One phenomenon that made a particularly lasting impression on

the islanders was the bountiful cargo that these strangers brought with them:

crates of canned food, medicine, clothes, and a variety of equipment that the Tanna islanders had rarely encountered. When the war ended

and the troops returned home, the source of this bounty dried up, and these

islanders, unfamiliar with the modern manufacturing process and seeking to

ascertain the provenance of this wealth, reproduced some of the features and

practices that accompanied it, hoping ultimately that the cargo – perceived

physical and spiritual wealth, equality, and political autonomy – might return

to bless their islands again.

Too often, Western policy recommendations for the development of poorer

nations are not that different from these ‘renewing rituals’ of the Tanna islanders. They involve a superficial imitation of

institutions that correlate with economic prosperity in developed countries,

without proper consideration of the underlying conditions that allow them to

generate wealth – circumstances that may not exist in the poorer countries. In

particular, the conventional wisdom has been that poverty in the developing

world is predominantly the result of improper economic and governmental

policies and it can therefore be eradicated through the application of a

universal set of structural reforms. This presumption has been based on a

fundamental misconception since it ignores the critical impact of deep-rooted

factors on the efficacy of such policies. An effective strategy would grapple

instead with these primary factors as they are the ones that have invariably

hindered the growth process and they often differ radically from one country to

another.

One conspicuous example of this misguided approach is the Washington

Consensus – a set of policy recommendations for developing countries focused on

trade liberalization, the privatization of government-owned enterprises,

greater protections for property rights, deregulation, broadening the tax base,

and reducing marginal tax rates. Despite intense efforts by the World Bank and

the International Monetary Fund to implement Washington Consensus–inspired

reforms in the 1990s, they have had limited success in producing the desired

results. Privatization of industry, trade liberalization and secure property

rights might be growth-conducive policies for countries that have already

developed the social and cultural prerequisites for economic growth, but in

environments where these foundations are absent, where social cohesion is

tenuous and corruption well entrenched, such universal reforms have often been

fruitless.

No reforms, however efficient they may be, will transform impoverished

nations into advanced economies overnight because much of the gulf between

developed and developing economies is rooted in millennia-long processes.

Institutional, cultural, geographical and societal characteristics that emerged

in the distant past have propelled civilizations through their distinct

historical routes and fostered the divergence in the wealth of nations.

Incontestably, cultures and institutions conducive to economic prosperity can

be gradually adopted and formed. Barriers erected by aspects of geography and diversity

can be mitigated. But any such interventions that ignore the particular

characteristics that have emerged over the course of each country’s journey are

unlikely to reduce inequality and may instead provoke frustration, turmoil, and

prolong stagnation.

At the outer layer of the roots of inequality are the asymmetric

effects of globalization and colonization. These processes intensified the pace

of industrialization and development in Western European nations while delaying

the escape of less-developed societies from their poverty trap. The persistence

of extractive colonial institutions in some regions of the world, designed to

perpetuate existing economic and political inequalities, exacerbated this gap

in the wealth of nations even further.

Nevertheless, these forces of domination, exploitation, and asymmetric

trade during the colonial age were predicated on uneven development prior to

the colonial era. Pre-existing regional differences in political and economic

institutions, as well as in prevailing cultural norms, had a governing

influence on the pace of development and the timing of the transition from

stagnation to growth.

Institutional reforms at critical junctures in the course of human

history as well as the emergence of distinct cultural characteristics have

occasionally placed societies on diverging growth trajectories over time.

Nevertheless, random events – dramatic and substantial as they loom in our

minds – have played a transitory and largely limited role in the progression of

humanity as a whole and they are very unlikely to be the dominating factors

behind the divergence in economic prosperity between countries and regions in

the past few centuries. It is not a coincidence that the first great

civilizations arose in fertile lands around major rivers, such as the

Euphrates, Tigris, Nile, Yangtze, and Ganges. No random historical,

institutional or cultural developments could have triggered the formation of

major ancient cities far from sources of water, or developed revolutionary

agricultural technologies in the heart of the frostbitten forests of Siberia or

in the middle of the Sahara Desert.

At the inner layer, deeper factors rooted in geography and the distant

past often underpinned the emergence of growth-enhancing cultural characteristics

and political institutions in some regions of the world and growth-hindering

ones in others. In places, such as Central America, the suitability of land for

large plantations fostered the emergence and persistence of extractive

political institutions characterized by exploitation, slavery, and inequity. In

others, such as sub-Saharan Africa, the disease environment contributed to

lower agricultural and labor productivity and delayed the adoption of more

advanced agricultural technologies, diminishing population density, political

centralization, and long-run prosperity. In more fortunate regions, by

contrast, favorable soil and climatic characteristics triggered the evolution

of cultural traits conducive for development – a greater inclination towards cooperation,

trust, gender equality, and a stronger future-oriented mindset.

An appreciation of the long-lasting impact of geographical

characteristics led us 12,000 years back in time to the dawn of the

Agricultural Revolution. During this period, biodiversity, the availability of

domesticable species of plants and animals, and the orientation of the

continents fostered an earlier transition from hunter-gatherer tribes to

sedentary agricultural communities in some places and a later transition in

others. Indeed, regions in Eurasia where the Neolithic Revolution took place

earlier enjoyed a technological head start that persisted during the entire

pre-industrial era. Importantly, however, the beneficial forces associated with

this earlier transition to agriculture dissipated in the industrial era and

ultimately have played a limited role in forging the extensive inequality

across the globe today; societies who made the transition to agriculture

earliest were not destined to become the most prosperous nations in the

present, as their agricultural specialization eventually hindered the process

of urbanization and mitigated their technological head start.

Ultimately, the quest for some of the deepest roots of modern-day

prosperity led us further back to where it all began: the initial steps of the

human species out of Africa, tens of thousands of years ago. The degree of

diversity within each society, as determined partly by the course of that

exodus, has had a long-lasting effect on economic prosperity over the entire

course of human history – with those who enjoyed the sweet spot of

innovation-inducing cross-fertilization and social cohesiveness benefiting

most.

In recent decades, the rapid diffusion of development among poorer

countries has promoted the adoption of growth-enhancing cultural and

institutional characteristics in all regions of the world and contributed to

the growth of developing nations. Modern transportation, medical and

information technologies have diminished the adverse effects of geography on

economic development, and the intensification of technological progress has

further enhanced the potential benefits of diversity for prosperity. If these

trends were combined with policies that enabled diverse societies to achieve

greater social cohesion and homogeneous ones to benefit from intellectual

cross-pollination, then we could begin to address contemporary wealth

inequalities at their very roots. Today on Tanna

Island, one can find a real airport; primary schools are available for most

children; islanders own mobile phones; and streams of tourists, attracted by

the Mount Yasur volcano and traditional culture,

provide vital revenues to the local economy. While income per capita in the

nation of Vanuatu to which the Island belongs is still very modest, it has more

than doubled in the past two decades. Despite the long shadow of history, the

fate of nations has not been carved in stone. As the great cogs that have

governed the journey of humanity continue to turn, measures that enhance future

orientation, education, and innovation, along with gender equality, pluralism,

and respect for difference, hold the key to universal prosperity.

Conclusion

It has long been the prevailing wisdom that living standards have risen

incrementally over the entire course of human history. This is a distortion.

While the evolution of technology has indeed been a largely gradual process,

accelerating over time, it has not resulted in a corresponding improvement in

living conditions. The astounding ascent in the quality of life in the past

centuries has in fact been the product of an abrupt transformation.

from the emergence of Homo sapiens as a distinct species nearly 300,000

years ago, the basic thrust of human life was remarkably similar to that of a

squirrel, defined by the pursuit of survival and reproduction. Living standards

bordered on the subsistence level and scarcely varied over the millennia or

across the globe. But perplexingly, over the past few centuries, our mode of

existence has been drastically transformed. From a historical standpoint,

humankind has experienced a dramatic and unprecedented improvement in the

quality of life virtually overnight..

The unique forces that permitted humanity to journey from stagnation to

growth, and then to inequality, a path that squirrels – or any other species

residing on Planet Earth – may never take. Recognizing that attempts to

describe the entire course of the history of the human species are likely to be

overwhelmed by fascinating details that may obscure the holistic view, I have

strived to focus on the fundamental forces that have swept humanity along its

voyage.

Ever since the development of the first stone-cutting tool,

technological progress fostered the growth and the adaptation of the human

population to its changing environment. In turn, these changes generated

further technological progress across time and space – in every age, in every

region, and in each and every civilization. Nevertheless, one central aspect of

all societies remained largely unaffected: living standards. Technological

advancements failed to generate long-term betterment in the material well-being

of the population. Like all other species, humanity was caught in a poverty

trap. Technological progress unfailingly generated a larger population, mandating

that the bounty of progress had to be divided among growing numbers of souls.

Innovations engendered economic prosperity for a few generations, but

ultimately, population growth

For millennia, the wheels of change – the reinforcing interplay between

technological progress and the size and composition of the human population –

turned at an ever-increasing pace until, eventually, a tipping point was

reached, unleashing the rapid technological progress of the Industrial

Revolution. The increasing demand for educated workers who could navigate this

rapidly changing technological environment, combined with a decline in the

gender wage gap, provided parents with a greater incentive to invest in the

education of their existing children instead of giving birth to additional

ones, triggering a fertility decline. The Demographic Transition shattered the

Malthusian poverty trap, living standards improved without being swiftly

counterbalanced by a population boom, and thus began a long-term rise in human

prosperity.

Nonetheless, while billions of people have been liberated from the

vulnerability to hunger, disease, and climatic volatility, a new peril looms

over the horizon: the alarming impact of human-caused environmental degradation

and climate change, originating during the Industrial Revolution. Will global

warming be viewed in a few decades as the historical event that derailed

humanity from its relentless march? Intriguingly, the parallel impact that

industrialization had on innovation, human capital formation, and fertility

decline may well hold the key to the mitigation of its adverse effects on

climate change and the potential trade-off between economic growth and

environmental preservation. The rapid decline in population growth, the

increase in human capital formation, and the capacity for innovativeness that

have been sweeping the globe in the past century provide grounds for optimism

regarding our species’ ability to avert the most devastating consequences of

global warming.

Since the dawn of the nineteenth century, living conditions have taken

an unparalleled leap forward by every conceivable measure, as reflected in the

rapid expansion of access to education, health infrastructure, and

technologies, forces that have radically transformed the lives of billions of

people across the world. Nevertheless, our escape from the epoch of stagnation

has occurred at different times across the globe. Western European countries

and regions of North America experienced the remarkable leap in living

conditions in the immediate aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, whereas in

most regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America the transition did not take

place until the latter half of the twentieth century – spurring vast

disparities in wealth and well-being. But there are grounds for optimism here,

as well. Admittedly, regional differences in institutions, culture, geography,

and diversity will not disappear entirely; we know how lasting these factors

can be. Over time, though, cultural and technological diffusion, as well as

diversity-related policies, could bridge some of these gaps and mitigate the

impact of these deep-rooted factors. It should not be long before the

Malthusian forces fade from our collective memory and humanity as a whole

embarks on a new phase in its journey.

Highlighting the incredible progress of the past two centuries should

not diminish the significance of the misery and injustice that continue to

affect a large portion of humanity, nor the urgency of our responsibility to

address them. Rather, my hope is that an understanding of the origins of this

inequality will empower us with better approaches to the alleviation of poverty

and contribute to the prosperity of humanity as a whole. Recognizing our roots

will permit us to participate in the design of our futures. The uplifting

realization that the great cogs of human history have continued whirring apace

in recent decades, contributing to the global diffusion of economic prosperity,

should sharpen our appetite to seize what is within our grasp.

For as long as humans have been self-reflective, thinkers have wondered

about the rise and fall of nations and the origins of wealth and inequality.

Now, thanks to long-term perspectives born from decades of investigation, as

well as an empirically based unifying framework of analysis, we have the tools

to understand the journey of humanity in its entirety, and to resolve its

central mysteries. My hope is that our understanding of the origins of wealth

and global inequality will guide us in the design of policies that facilitate

prosperity over the world and allow readers to envision – and strive for – the

even more bountiful future that lies ahead, as the human species continues its

journey into uncharted territories.

For updates click hompage here